A few weeks ago, I had the chance to meet the two dozen or so sports medicine doctors who take care of the Netherlands Olympic team. With Tokyo 2020 looming on the horizon, they’d gathered at National Sports Centre Papendal, a sprawling, forested athletic mega-campus on the outskirts of the city of��Arnhem, for two days of meetings, discussions, and debates. One of the topics was how to weigh imperfect scientific evidence when you’re dealing with elite athletes, for whom even a tiny edge might be the difference between glory and oblivion—a topic I wrestled with in a recent in-depth article��about the performance-boosting effects of electric brain stimulation.

At dinner after the first day’s discussions, I happened to be seated across from an Amsterdam-based doctor named Guus Reurink. His doctoral thesis was on hamstring injuries, including a 2014 randomized trial that found no benefit to platelet-rich plasma injections, better known as PRP. That got my attention, because about a decade ago PRP was the hottest thing in sports medicine, touted to speed��the healing of tendons, joints, muscles, and pretty much any other body part you can think of. But you don’t hear as much about it these days. What, I asked Reurink, was its current status?

It turns out to be complicated. PRP, in a nutshell, involves withdrawing some blood, spinning it in a centrifuge to separate out the platelets that are thought to play a key role in instigating healing, then reinjecting the good stuff at an injury site. As Reurink’s work showed, it doesn’t seem to work for hamstring injuries. Neither does it seem to work for Achilles tendons, muscle injuries more generally, bone fractures, or ACL repairs, according to ��last year. On the other hand, it seems to work for tennis elbow and knee osteoarthritis, and may work for patellar tendinopathy and plantar fasciitis.

In other words, it’s a mess. Given that it supposedly works for some tendons but not others, and some joints but others, it’s easy to see why, when an injured elite athlete comes in desperately looking to get healthy as quickly as possible, you might say, “Well, let’s give PRP a shot. It might help, and can’t hurt.” It’s precisely the same logic that leads some athletes to wire themselves up for electric brain stimulation.

But Reurink was more hesitant about the therapy��than I expected. Some of the best evidence for injury healing, he pointed out, backs the use of progressive exercise programs. Even in situations where PRP appears to work, like knee osteoarthritis, its benefits are fairly similar to what you’d expect to see from a leg strengthening program. Patients, of course, prefer the quick fix. It’s much more satisfying to walk out of the doctor’s office with an appointment for an injection than with instructions to spend several months at home doing seemingly pointless exercises. And it’s much easier—and more lucrative—for doctors to promise an injection than to spend an hour explaining why an injection isn’t needed.

It may be a bad trade-off, though. Reurink directed me to a study ��in 2017 that compared PRP, exercise, and the combination of both for muscle injuries in rats. There are obvious downsides to rat studies, but the advantage is that you can induce pretty much identical injuries, and then you can directly analyze the muscle tissue to determine how well it healed and why. Also, rats don’t slack off of their exercise program just because they got an injection.

The study, from researchers at Vall d’Hebron Institut de Recerca in Spain, assigned 40 rats to one of five different groups: a single PRP injection; daily exercise training for two weeks; both PRP and exercise; an injection of saline as a placebo; or no treatment at all. The good news: both PRP and exercise accelerated recovery and improved other markers of healing compared to doing nothing at all or getting a placebo. But the most interesting finding was what happened to the group that got both exercise and PRP.

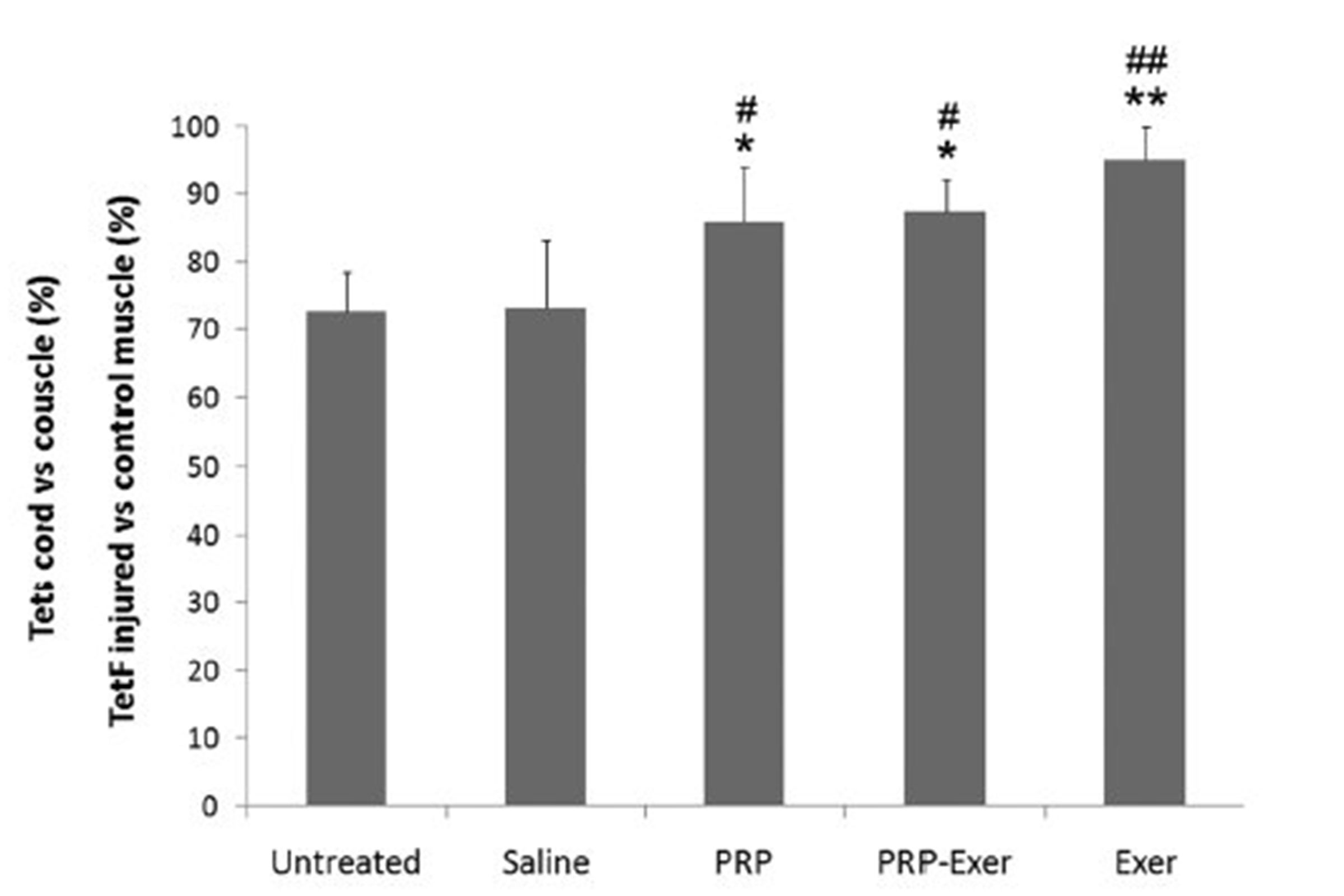

Here’s the muscle strength of the injured legs��compared to the��healthy ones��after two weeks of recovery, as��measured by electrically stimulating the muscles. A value of 100 percent would mean that the injured muscle had fully recovered and was just as strong as the uninjured muscle.��

Again, PRP is better than nothing, and also better than the placebo injection of saline. Exercise is even better than PRP. If you get both PRP and exercise? It’s not as good as exercise alone. Somehow, getting the PRP injection interferes with the benefits of active recovery.

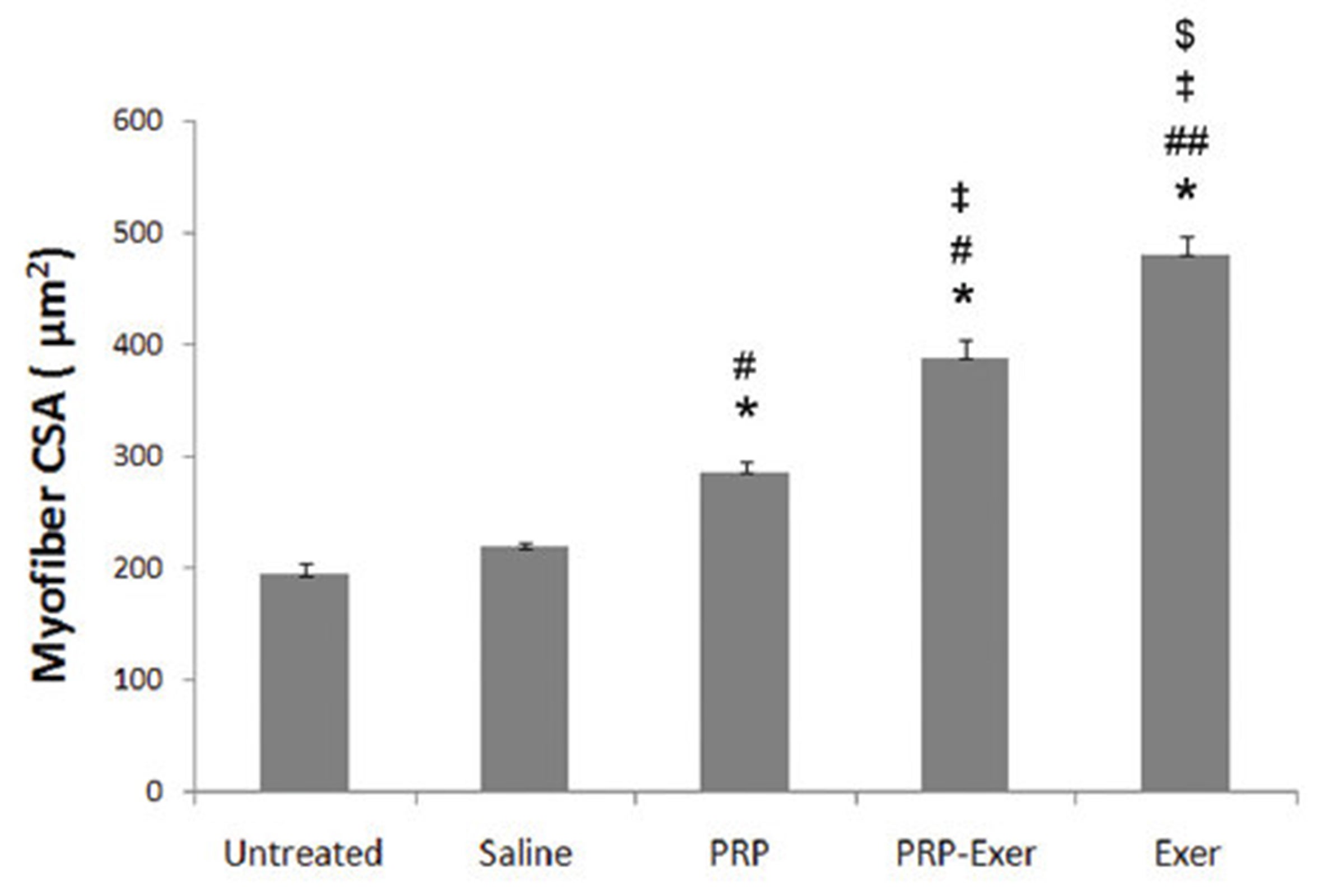

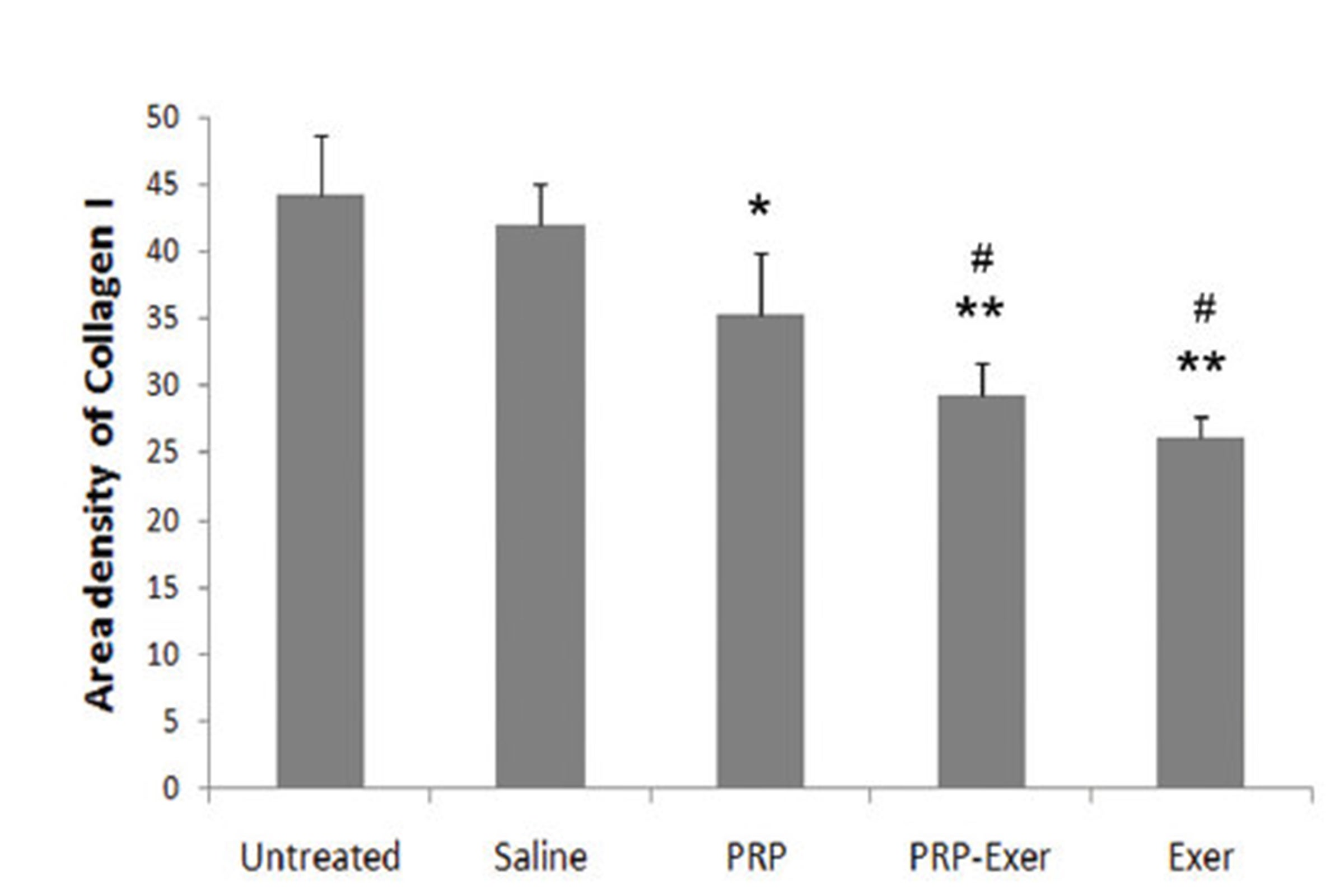

Other data suggests that this finding isn’t just a fluke. In pretty much all the outcome measures, PRP is good, exercise is better, and doing both is somewhere in the middle.��In the first graph below, for example, is the average cross-sectional area (in millimeters) of newly formed individual muscle fibers in the injured muscle. Bigger is better. In the second graph, you have a measure of the amount of scar tissue in the injured muscle, expressed as a percentage of the muscle’s total cross-sectional area. In this case, smaller is better.

These findings, the researchers suggest, may help explain why studies of PRP have produced such mixed results: it depends not only on what you’re comparing PRP to, but also on what else the injured subjects are doing. If they’re doing nothing, PRP looks great. But if they’re also doing a fairly standard rehabilitation protocol that includes exercise, PRP may actually interfere with its benefits.

Of course, I should emphasize again that rats injuries and human injuries may differ in some unexpected way. Perhaps these results don’t apply directly to humans. But I think they illustrate a more general point that applies not just to PRP, but also to other cutting-edge therapies and technologies, including brain stimulation: nothing takes place in a vacuum. Adding one element to your routine, be it ice baths��or ketones��or all-out sprints, will interact with other parts of your regimen, and not always for the better. And even if there’s no direct interaction, the time, energy, and money you choose to spend in any one area comes with opportunity costs in other areas. That doesn’t mean you should never try anything new. It just means you should understand that there’s always a cost.

My new book, , with a foreword by Malcolm Gladwell, is now available. For more, join me on ��and , and sign up for the Sweat Science .