Is Brain Stimulation the Next Big Thing?

Over the past decade, athletes, coaches, and researchers have been seduced by the performance-boosting promises of brain stimulation. On a ride-and-zap-your-brain-like-the-pros tour through the Alps, Alex Hutchinson wonders whether it really works—and whether we want it to.

New perk: Easily find new routes and hidden gems, upcoming running events, and more near you. Your weekly Local Running Newsletter has everything you need to lace up! .

For the first 20 miles of the ride up the Col du Galibier—the storied Alpine climb that debuted in the Tour de France back in 1911, when all but three riders were forced to dismount and walk their chunky pre-carbon-fiber velocipedes to the 8,000-foot summit—I was actually enjoying myself, more or less. The other cyclists on my weeklong tour had decided to bag it and hop in the support van halfway up the climb, as the temperature began to plummet and a cold rain swept down from the surrounding peaks. So had Massimo, our cheerfully inscrutable, Dante-quoting bike guide, who preferred the warmer climes of his native Sardinia. I was alone with the mountain, savoring the subtle gradations of my rising distress.

With a couple miles to go, though, the novelty started to wear off. The rain turned to sleet, and as I switchbacked through canyon-like passageways formed by monstrous ten-foot snowbanks, my hands, in their sodden gloves, became too numb to operate my gears—more of a theoretical problem than an actual one, since I was too spent to get out of my lowest gear anyway. As I neared the summit, the grade seemed to keep getting steeper, the headwind stronger, and my insistence on finishing the climb under my own power more foolish.

Instead of the ghosts of Coppi and Merckx and other bygone stars who’d triumphed here, I found myself chasing the flowing locks of Fabian Cancellara, the flamboyant Swiss rider who was famously (some would say outrageously) accused of hiding a tiny electric motor in his bike in 2010. As a novice cyclist embarking on an ambitious itinerary called , I had seriously considered requesting one of the e-bikes offered by my tour company, just to make sure I wouldn’t hold my more experienced trip mates back. Now I contemplated Fabian’s choice: If I had a Go button on my bike, would I press it?

As I turned yet another corner, with less than half a mile to go, the easterly headwind became a virtual wall. I had to get out of my saddle and lean into a wobbly, slow-motion sprint just to avoid slowing to a complete halt and toppling over sideways. By the time I turned away from the wind a few hundred yards later, my heart rate and breathing were fully maxed out and my legs were jelly. I knew I couldn’t face the gale again. Then I saw that, instead of another hairpin, the road ahead snaked up the rest of the way to the summit without turning back into the wind. I pedaled onward, with a mix of pride and relief—pride that I’d made it, relief that my bike hadn’t, after all, been equipped with a motor that would have tempted me to take an electric shortcut.

A few minutes later, I was thawing in a cozy bistro on the far side of the summit, sipping hot chocolate, with a plush hotel-style bathrobe draped over my shivering shoulders. That’s when an uncomfortable thought struck me: Why should I disparage the boost provided by an electric motor when, that very morning, with precisely the same goal, I’d sat patiently in a hotel lounge while a neuropsychologist trickled electric current through a web of electrodes gelled to my scalp?

Really it was just a matter of time. Back in 2013, when Brazilian scientists that a relatively simple protocol of transcranial direct-current stimulation (tDCS) to the brain seemed to enhance endurance, you could already map out the events that would follow: the flood of copycat studies, the launch of peddling the technique to early adopters, the murky reports of professional athletes and teams like the and the experimenting with it, the about fairness and safety, and, finally, the press release that showed up in my inbox in January of this year—the field’s “Holy shit, they’re using Crispr on human embryos!” moment.

The pitch was from , a spin-off of ’s official sports-medicine clinic, the (IRR), based in Turin, Italy. It had enlisted a bike-touring company called Tourissimo, also based in Turin, to run the logistics for a bespoke trip, giving well-heeled amateurs the opportunity to spend a week riding famous Grand Tour passes while eating gourmet meals and receiving “advanced neurostim protocols used by the world’s top riders” for a cool $7,000 plus airfare. Before tackling the Colle delle Finestre, in the Piedmontese Alps of northern Italy, you’d get your prefrontal cortex stimulated to “enhance performance, mood, and the propensity to enter flow states.” After the Col d’Izoard, across the border in France’s Hautes-Alpes region, you’d hit your upper motor cortex “to enhance the central nervous system’s role in natural recovery processes.”

It read like an elaborate piece of satire. But it’s not: the technology is, on at least some level, real, and after six years of speculation and hype, someone was bound to start promoting it to the recreational market. It occurred to me that a tour for weekend warriors run by scientists also working with a top UCI cycling team would offer a unique opportunity to delve into some of the lingering questions about tDCS. Not just the obvious ones—does it work? is it safe?—but also trickier ones about fairness, technological innovation, and the deeper meaning of sport for those of us whose wins and losses are personal and unremunerated. So in early June, I buckled into a red-eye to Turin for a week of hard climbs, fine wines, and credulity-stretching neuroelectrophysiology.

The technology is, on at least some level, real, and after six years of speculation and hype, someone was bound to start promoting it to the recreational market.

The idea that a jolt to your brain might enhance your physical powers isn’t quite as futuristic as it sounds. A published in Psychological Medicine in 2016 traces the technique’s lineage back to Roman times, when an imperial physician named Scribonius Largus prescribed a live torpedo fish to the scalp to relieve headaches. Similar ideas crop up in cultures around the world, but the modern incarnation of tDCS began in the late 1990s and took off a decade or so later. The basic idea is simple: your brain is like a vast interconnected circuit, with neurons that communicate with each other via electric discharges. Applying a very weak current of a few milliamperes tweaks the excitability of the affected neurons, such that they become a little more (or, if you run the current in the opposite direction, less) likely to fire in response to whatever you do in the subsequent hour or two. Exactly what that means depends on which parts of the brain you hook up, but the general upshot is that different brain regions are able to communicate with each other more easily—which, if you believe the hype, can have effects ranging from changing your mood to making you a better sniper. All it takes, as a vibrant and somewhat scary online DIY subculture attests, is a nine-volt battery and a couple of electrodes.

Of course, wiring up your brain still carries some pretty weighty cultural associations. When Massimo, the Tourissimo cycling guide, picked me up at the airport, I found that he was as bemused by the whole thing as I was. As we dodged and weaved through Turin’s Saturday-morning traffic, he outlined the plan: he would take me back to the hotel for lunch and a brief rest, then I’d get fitted for a bike, then he would take me to the IRR clinic for my first—as he described it, air quotes and all—“treatment.” I’d be joined by two other cycling journalists from Britain for NeuroFire’s maiden tour, he said, since no paying customers had actually signed up. Still, “we have another testimonial,” he added cheerfully. “It’s .”

At the clinic, a sleek complex with ultramodern furniture, rows of sophisticated rehab equipment, and the high-wattage brightness of a toothpaste commercial, we met a half dozen members of the tour’s medical and support staff. The plan for the week, they explained, had two main parts. For our first three days of cycling, we would receive 20 minutes of brain stimulation immediately before riding, with the electrodes positioned on our scalp in a configuration designed to enhance our performance, perhaps by kicking us into a flow state for the first hour or two of the ride. For the last two days, as the cumulative fatigue of tens of thousands of feet of climbing mounted, we would switch to 20 minutes of stimulation immediately after riding, this time with an electrode configuration chosen to enhance the recuperative powers of the massage we would receive simultaneously as our synapses sizzled.

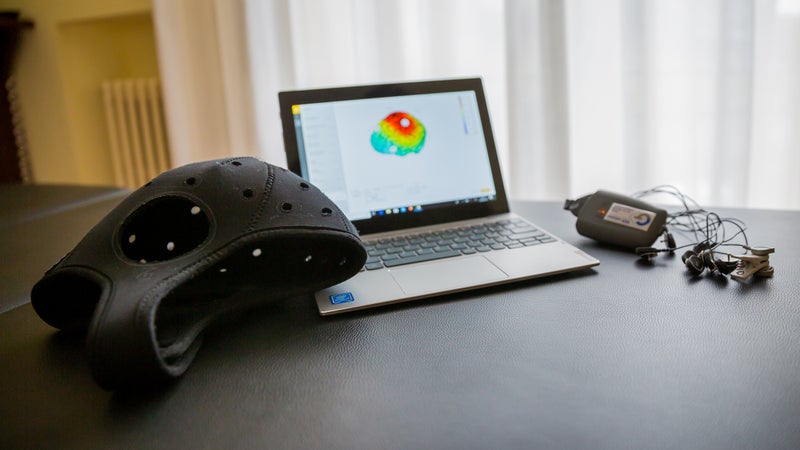

But first we needed some baseline testing to figure out where the electrodes should be placed on each of us. A neuropsychologist from the IRR named Elisabetta Geda ushered me down a corridor, past rows of glossy pamphlets and posters displaying before-and-after tummy pics from exotic treatments like “full-body contouring by cryoadypolisis,” to a quiet room where she pulled a neoprene cap studded with electrodes over my scalp. As I visualized cycling up a mountain road, she used electroencephalography (EEG) to monitor the communication between different regions of my brain. “The brain signals are like an orchestra,” she explained. “Every section has a rhythm, and we record these rhythms with EEG. Then we can personalize your electrode montage, because each person may need a different treatment.”

Geda and her colleagues at the rehabilitation clinic have been using tDCS for several years on patients with conditions like chronic pain, addiction, fatigue related to multiple sclerosis, and cognitive deficits after traumatic brain injury. They use it in combination with existing treatments, priming the appropriate neurons to fire more readily in order to amplify the benefits of those therapies. So in 2017, when the IRR signed on as the official sports-medicine provider for the new Bahrain Merida cycling team, Geda began to consider the technique’s athletic potential. She and her collaborators ran a study replicating the 2013 Brazilian results, then floated the idea to Bahrain Merida.

The initial response was lukewarm. “At the beginning, we were a little bit afraid,” Luca Pollastri, one of the cycling team’s medical doctors told me. “We took some time to understand what’s going on, what’s legitimate, what’s the World Anti-Doping Agency’s position, and so on.” Instead of using it to directly enhance performance, Pollastri asked Geda if she could devise a protocol that would help athletes relax and recover after racing, which is a major challenge in Grand Tours, when riders are going to the well day after day for weeks. Geda suggested stimulating the brain during massage, effectively amplifying the massage’s effects on the central nervous system—an unorthodox approach that no one else had tried.

Among the first riders to try it was Domenico Pozzovivo, an Italian climbing specialist known in the peloton as the Doctor for his cerebral approach—not Bahrain Merida’s star, but someone happy to experiment with new ideas and capable of giving detailed feedback about them. In the 2018 Giro d’Italia, Pozzovivo started using tDCS to boost his recovery a few stages into the race. Night after night, he faithfully donned the electrodes for a massage, and after 17 stages, he found himself in third position in the general classification: on track, at age 35, for his first-ever Grand Tour podium. But the complicated logistics of a grueling mountaintop finish in the resort town of Prato Nevoso meant that he missed his session after the 18th stage, and, for the first time in the race, he slept poorly. The next day, he lost eight minutes to the leader and slipped back to sixth overall, before rallying in the final two stages to finish fifth. To the staff at Bahrain Merida, and to Pozzovivo himself, neither his career-best overall performance nor the timing of his one bad day seemed like a coincidence.

By this time, Pollastri and his colleagues were ready to consider using the technique as a prerace booster. With Gabriele Gallo, a sports scientist at the University of Milan, they brought ten cyclists from Bahrain Merida’s continental team to the lab for a double-blind series of simulated 15-kilometer time trials with real and sham tDCS. For a roughly 20-minute effort, the riders averaged 16 seconds faster with tDCS, right on the margins of a statistically significant improvement. It was suggestive enough that they decided to use it at the opening stage of the 2019 Tour de Romandie, where Slovenian rider Jan Tratnik took the win for Bahrain Merida.

On the morning after our EEG tests, we met Geda in a conference room in the imposingly ornate Grand Hotel Sitea for our first treatment before a test ride up the Colle della Maddalena, one of the hills across the Po River from downtown Turin. When I apologized for encroaching on her Sunday, Geda waved me off: she’d sent her two toddlers to their grandmother’s for the weekend so she could focus on the tour. “This is like a holiday for me,” she laughed. Pulling up a 3-D model of the human brain on her computer, she outlined the results of the previous day’s EEG tests.

Trevor Ward, one of the British journalists, apparently had “a great connection” between his prefrontal and motor cortices—between perception and action, in effect. This is characteristic of elite athletes, Geda explained, so he would receive the same six-electrode tDCS stimulation that the pros got, focusing on the prefrontal cortex (PFC) itself. That’s the region of the brain that integrates information from everywhere else and decides whether and when you can push harder. “Our theory is that the PFC is less active during exercise because other regions are overloaded,” Gallo explained. “So if we stimulate this area, the athlete should have better regulation of pacing.”

The other Brit, John Whitney, and I were not so accomplished, so we’d get a remedial eight-electrode stimulation to help nurture the crucial prefrontal-motor connection in addition to stimulating the PFC. Geda slid the neoprene cap onto my head, and I felt a mild prickling in my scalp as one milliampere of current began to flow. A minute or so later, the sensation faded to nothing, and for the rest of the 20 minutes, I simply sat back and relaxed.

After a short ride through the cobbled maze of Turin’s pedestrian core (and the requisite stop for espresso), we crossed the Po and started climbing. As we pedaled up the incline, I felt a little buzzed and a little jet-lagged, and my bike felt about half as heavy as usual—which it was, since I’d trained for the trip on an aging mountain bike and was now riding a $6,000 carbon-frame Bianchi. Joining us for the ride was Vittoria Bussi, the reigning world-record holder for the one-hour time trial, and I fell in beside her to get her take on the technology.

I felt a little buzzed and a little jet-lagged, and my bike felt about half as heavy as usual—which it was, since I’d trained for the trip on an aging mountain bike and was now riding a $6,000 carbon-frame Bianchi.

Bussi, it turned out, had just returned from a time trial in Slovenia, where she’d been accompanied by Geda to try prerace tDCS. Bussi hadn’t detected any difference in performance or power output, but her heart rate had been lower than usual—a somewhat ambiguous result that she’d also noticed in a previous experiment with the technique. A compulsive tinkerer, with a Ph.D. in math from the University of Oxford, Bussi saw tDCS as just another element of the continual process of experimentation, quantification, and optimization that cycling permits. “I’m curious,” she said. “I like trying to figure out the best possible approach to a problem.” Overall, the race in Slovenia had been a success, with a third-place finish that boded well for her goal of qualifying for the 2020 Olympics. She figured she’d keep using brain stimulation, at least for a while.

As for me—well, I never expected to feel any magical gains from brain stimulation. (Don’t tell my editor.) My pace up the Colle della Maddalena, or any other hill, would be determined by how hard it felt. If the effort that felt sustainable happened to get me to the top a percent or two faster than normal, how would I possibly detect such a subtle difference? At best, the cumulative effects of each day’s brain stimulation would leave me a little fresher as the week (and its 37,000 feet of climbing) proceeded—better able to enjoy the evening feasts, less likely to end up in the sag wagon. But for any given ride, the only useful way to judge something like this is with well-designed research, preferably double-blind and peer-reviewed. Trust the data, not your easily deluded intuition.

Even the data, however, is far from definitive on tDCS. The U.S. National Library of Medicine lists more than 5,000 tDCS studies, the vast majority from the past decade. The technique (or maybe ),������ (or maybe ),������ (or maybe ), and on and on for a seemingly limitless variety of conditions. There’s a ton of hype and a corresponding amount of backlash. One researcher the field as “a sea of bullshit and bad science.”

The sports applications of tDCS face a similarly muddled situation. A in Frontiers in Physiology in 2017 identified 12 studies of brain stimulation and exercise performance, eight of which found a performance boost. Conversely, two meta-analyses of and studies published in Brain Stimulation in 2019 concluded that the evidence in favor of an athletic boost is somewhere between slim and nonexistent. Part of the problem is that different studies use different protocols, electrode montages, and exercise tests. Some stimulate the motor cortex, hoping to facilitate a stronger output signal from brain to muscle. That’s the approach that consumer-tech startup Halo Neuroscience uses for its $400 brain-stimulating headphones. Other studies stimulate the regions responsible for evaluating inputs to the brain, hoping to dull the sensation of effort. Geda and Pollastri, by focusing on the prefrontal cortex, take yet another approach.

To skeptics, peering at this hodgepodge of conflicting evidence and concluding that brain stimulation will make you faster sounds a lot like wishful thinking. In July, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Calgary named James Wrightson posted a preprint (a finished paper that is posted publicly for comment prior to being submitted for peer review) of his latest study, which found no effect of tDCS to the motor cortex on leg endurance. A crucial detail: Wrightson’s study protocol had been , meaning that he decided in advance how his data would be analyzed, and he committed to sharing the results regardless of whether or not they confirmed his hypothesis. How many of the small, positive reports of tDCS’s athletic effects, he wondered, might be explained by or counterbalanced by negative studies that no one bothered to publish?

These issues aren’t unique to tDCS research, of course. In fact, they apply to pretty much any sexy and “science-backed” performance aid these days. Wrightson is a passionate advocate of more rigorous methodology in sports science, which lags behind other fields, like neuroscience, in insisting on things like preregistration and large sample sizes that reduce the likelihood of spurious results. His own study, with 22 subjects, isn’t enough to prove that tDCS doesn’t work, he emphasized when I emailed to ask about his research. Many more studies, with far bigger sample sizes, are needed before we can draw any firm conclusions. Until then, his advice to athletes is to skip tDCS—and any other shiny new performance booster—until better evidence is available. “But athletes are always going to be athletes (and coaches, coaches),” he wrote, “so we’ll probably still see Halo devices everywhere at Tokyo 2020 anyway.”

From a scientific perspective—the Sisyphean pursuit of knowledge through the eternal evaluation and reevaluation of evidence, let’s say—Wrightson is undeniably correct. We don’t know shit about tDCS, scientifically speaking. But his comment about athletes being athletes, with the implication that anyone who tries an unproven technique like tDCS is a benighted dunce, struck me as unfair. Athletes are not trying to advance human knowledge or settle epistemological questions; they’re trying to win. If you have a technology with minimal cost, no known health risks, and there’s a plausible but unproven chance that it has real performance-boosting effects, isn’t it entirely rational to give it a try? Even ignoring placebo effects—another discussion entirely—there’s a small possibility of life-altering benefits for an elite athlete near the top of their sport, weighed against negligible downsides.

Wrightson, when I put this to him, didn’t buy it. In fact, he felt that even discussing preliminary research in fields like tDCS outside the hallowed halls of academia was highly irresponsible. Writing about tDCS in the “lay press,” as I had done on several occasions (and am doing right now, for that matter), was particularly egregious. “I think you were wrong to publish those articles so early,” he insisted. “It’s a hill I’m willing to die on.”

The first real hill of our tour, on Monday morning, was the Colle delle Finestre—the hero-making climb where, in last year’s Giro, Chris Froome made his winning 50-mile breakaway and where, after a restless night, Pozzovivo’s podium dreams died. We started our day in the Alpine town of Susa, lounging on folding chairs in a public park in the shadow of an imposing 2,000-year-old Roman arch as Geda gelled up the electrodes. But just before she cranked on the current, the ominous clouds above us unleashed a few warning drops. We barely had time to scramble back into the van, where I put in my 20 minutes of stimulation amid the drumbeat of torrential rain on the roof.

An hour later, the rain finally subsided, and we pedaled off, with Massimo setting the pace. We soon settled into a rhythm that would come to feel routine in the days to come, climbing steadily for 10 or 15 or 20 miles at a time, up average grades of 7 or 8 or 9 percent. There was almost no traffic, since other roads and tunnels now provide faster and more direct routes across the mountain passes. We saw nobody other than the occasional shepherd or blueberry picker, though we passed farmhouses and mountain refuges and ancient churches and monuments to cyclists of yore. It’s not like climbing the short, sharp hills that I encounter around my home in Toronto, where you can rely on momentum and a leg-burning sprint to get you to the crest. Instead you have to find a sustainable rhythm, so that the climb becomes not a frantic struggle but a meditative grind.

Just under five miles from the top of Colle delle Finestre, the asphalt ended. The rest of the road was gravel, wet and slippery thanks to the rain that was once again falling. I focused on following Massimo’s rear wheel, weaving between rocks and cutting across stream-washed gullies in the road. I felt surprisingly strong and was almost disappointed when we finally reached the stone monument to cycling star (and thrice-caught doper) Danilo di Luca at the summit. I’d have sworn the brain stimulation had worked, except that the rain-delayed start meant the performance-boosting window—about 90 minutes, Geda had told us—had closed long before we even hit the gravel.

The logistical challenges of combining brain stimulation with cycling, we now realized, weren’t trivial. Geda had brought enough equipment from the clinic to zap two of us at once, but when you added in the time needed to clean electrodes between users and so on, it took about an hour for the three of us. A fully booked tour with eight cyclists would have been even more chaotic, even with extra staff and equipment. Bahrain Merida encountered similar challenges: it had sprung for ten sophisticated clinical-grade tDCS machines, each costing thousands of dollars, but it didn’t have enough trained medical staff to administer the treatment to everyone at once; instead, it only used one or two machines at a time.

Even though we’d come for the explicit purpose of trying out the brain stimulation, Trevor, John, and I couldn’t help grumbling a bit over the next few days. When the morning sun was shining and the mountains beckoned, it felt wrong to spend precious blue-skied hours fiddling with electrodes or to delay our dinner after a long day in the saddle. There were moments, as I waited patiently on van seats and in lobbies and hotel rooms across Piedmont and Savoy, when I began to question the basic premise of the trip. Sometimes I worried that the technology didn’t really work. Other times I worried that it did.

I’m all for e-bikes in the appropriate context. But it’s also obvious that it would be both unfair and meaningless to win a race using a motor, like winning a marathon by wearing roller skates. Even if the only person you’re competing with is yourself, you wouldn’t celebrate a new best time on your favorite training route (or, God forbid, a Strava KOM) if it was battery powered. Despite the Olympic motto, we intuitively understand that simply going faster (or higher or stronger) without any restrictions is not the fundamental goal of sport. Instead, there’s something else that’s harder to articulate—what the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) vaguely and unhelpfully refers to as “the spirit of sport.”

For nearly four decades, Thomas Murray, president emeritus of the Hastings Center bioethics research institute, has been trying to pin that elusive spirit down. A research grant from the National Science Foundation in 1979 started him down the path of trying to understand why athletes do or don’t choose to dope, which in turn led to the question of what sport is really about. His conclusion, laid out in academic papers and a 2018 book called Good Sport: Why Our Games Matter and How Doping Undermines Them, is that the highest goal of athletic competition is “the virtuous perfection of natural talents.” “Virtuous is a loaded word,” he acknowledged when I phoned to get his thoughts on brain stimulation. “Absolutely it is. But it’s the right word.”

In some situations, virtue is easy to discern. Training, nutrition, and coaching are all widely sanctioned methods of honing your abilities. Taking a crowbar to your main rival’s kneecap is not. But the distinction is often more nuanced. “There’s a golf ball that flies straighter, but sport bans it,” he points out. “They also bar certain clubs that make it easier to hit accurate shots out of the rough.” The point isn’t that all technology is bad; it’s that slicing into the rough should have a penalty. So the key question, whether you’re talking about drugs or technology, isn’t: Does it make you better? It’s: Does it change the things athletes have to do, and the qualities they have to possess, to win?

As the athletic implications of tDCS have become apparent, academics have started grappling with the ethical questions, variously arguing that it should be allowed, or that it should be banned, or even that athletes should be tested and handicapped to ensure that everyone gets exactly the same net benefit from it. The argument that caught my attention, from a 2013 paper on “neurodoping” by British neuroscientist and psychologist Nick Davis, was that brain stimulation “mediates a person’s ability but does not enhance it in the strictest sense.” You don’t get extra energy or stronger muscles from tDCS; you just find it a little easier to access the energy and strength that’s already present within you. Why would we ban something that simply helps us dig a little deeper?

The key question, whether you’re talking about drugs or technology, isn’t: Does it make you better? It’s: Does it change the things athletes have to do, and the qualities they have to possess, to win?

To me, though, that internal struggle to push a little closer to your limits is an essential part of endurance sport—in a sense, it’s the fundamental, defining characteristic. Change that and you change what it takes to win. After all, if you could just push a button to extract every ounce of power from your quads, what mystery would remain? Why would anyone watch—or participate?

I expected Murray, a long-standing defender of anti-doping orthodoxy, to share my qualms. But when I tried to pin him down about tDCS, he hedged. “The mere fact that something is a biomedical technology and enhances performance is not enough to disqualify it,” he said. “It’s only when it disrupts the connections between natural talents and their perfection.” That’s a judgment that may differ from sport to sport: a barefoot ultrarunner might have a different take on the appropriate role of technology in their sport compared to a gear-happy triathlete. WADA itself, according to spokesman James Fitzgerald, is aware of the controversy and has discussed it with experts in the field but hasn’t yet seen “compelling evidence” that it breaks the rules.

There is, however, one final caveat, Murray acknowledged before hanging up: “Once an effective technology gets adopted in a sport, it becomes tyrannical. You have to use it.” If the pros start brain-zapping, don’t kid yourself that it won’t trickle down to college, high school, and even the weekend warriors.

The queen stage of our tour, with almost 9,000 feet of climbing over two historic passes, started in the crenellated French mountain town of Briançon. In the breakfast room of our hotel, I chatted with Umberto, the tour guide who (to his mild chagrin) had been assigned to drive the support van instead of cycle with us. He comes from a prominent Piedmontese mountaineering family and had trained and worked as a mountain guide before switching to cycling. His affection for the Alpine landscape around us was reverent, almost poetic, and I got the sense that he sees the world much as Reinhold Messner does: where you end up is less important than how you get there. “When I was a kid growing up in the mountains,” he told me when I delicately probed his views on our tech-assisted adventure, “sport was about you. Your quest. But our society pushes everything to extremes.”

Those words echoed in my head as we rolled out under the radiant blue sky to tackle first the 7,400-foot Col d’Izoard and then the 9,000-foot Colle dell’Agnello, which Hannibal and his elephants supposedly crossed en route to Rome more than 2,000 years ago. A few miles from the summit of Agnello, I got confused about my gears. Tailing Massimo, as I had all week, suddenly seemed too slow to stay upright, so with a muttered apology, I moved past him and essentially launched an attack. By the time I realized that I’d accidentally been in my third gear rather than my lowest one, I was too sheepish to admit my mistake, so I decided to simply carry on to the summit and let it all hang out. As on Galibier, I was soon living from switchback to switchback, stretching the elastic thinner and thinner, and not at all sure that it wouldn’t snap before I reached the top.

An hour later, after a long, wobbly descent along endless switchbacks, past startled ibexes licking salt from the recently deiced roads, I coasted into the rustic town of Sampeyre, truly a spent force. There waiting for me in the hotel were Geda and a physical therapist from the IRR. Before I knew it, I was lying facedown on a massage table, having my deltoids kneaded as Geda hooked my brain up to the old familiar juice. It was an extremely pleasant way to end an epic day. I’d made it to the top of Agnello successfully—success being defined by the nebulous but utterly unfakeable sense that I’d pushed as hard as I was capable of and then a little bit more. Now the high-voltage massage would supercharge my recovery and, according to Pozzovivo, deepen my slumbers. “I have to say that, for me, the quality of sleep improved,” he claimed in a post-Giro interview last year.

I’d made it to the top of Agnello successfully—success being defined by the nebulous but utterly unfakeable sense that I’d pushed as hard as I was capable of and then a little bit more.

For the record, the idea that tDCS massage should aid recovery is “highly speculative,” according to Samuele Marcora, a University of Kent expert on the brain’s role in fatigue, who has studied tDCS and cycling. That’s probably being diplomatic. Even Geda acknowledged that the recovery protocol is mostly based on clinical experience rather than research. The pre-ride protocol is more plausible and well supported, Marcora told me. But even then, he added, “caffeine and a session with a good sport psychologist are likely to be much more useful.”

I knew and agreed with all this. Really, I did. But as the week wore on, I’d slowly realized that my ostensible reasons for going on the trip—investigating whether tDCS actually works, reflecting on the role technology should play in sport—were to some extent convenient covers for a more personal obsession. As much as I consider myself a skeptic and Luddite who runs and bikes with nothing but a grimy vintage Timex Ironman, I’ve been drawn in repeatedly by a fascination with brain stimulation. (Much to the annoyance, it turns out, of people like James Wrightson.) I’ve flown to Los Angeles for a zany Red Bull experiment with it, tried Halo Neuroscience’s headphones, written a whole book chapter about it, and now biked across the Alps on a bespoke brain stim tour.

As someone who has spent decades trying to figure out what the edge really feels like, the truth is that I’m as fascinated as I am horrified by the prospect of inching a little closer. If you pin me down, I’d say WADA should at least ban the technique in competition, even if, like stimulants and cannabis, it remains permitted in training. But I absolutely want to know with greater certainty whether it truly boosts endurance. Because if it does, that tells us something profound about the nature of our limits—that they’re in our neurons, not our muscle fibers. Maybe that’s what keeps drawing me back to the topic: the desire to find out if the edge I’ve been skirting all this time is just an illusion.

These are the riddles I was pondering when I finally flicked off my bedside lamp after my Herculean effort on Agnello and the subsequent massage. And for the first time since the trip began, I lay awake in the dark for nearly two hours, tossing and turning while my mind continued to race. Maybe it was because of the brain stimulation, or maybe it was despite it. Maybe it was the long day in the saddle, or the ill-advised third helping of gnocchi in butter, or the imponderable depth of the questions I was wrestling with. I’ll never know for sure—unless, as my history suggests is likely, I wire myself up again sometime.