“It Just Consumed Me”

Normally, not something you want a shark scientist to say. But Eric Stroud is talking about his chemistry-lab quest for the ultimate shark repellent, which he appears to have found. The questions that remain: Does it work on the great white, the ocean’s most fearsome predator? And can a couple of rookie entrepreneurs get it to market?

New perk: Easily find new routes and hidden gems, upcoming running events, and more near you. Your weekly Local Running Newsletter has everything you need to lace up! .

There's a house in Mossel Bay, South Africa, high on a hill overlooking the Indian Ocean, five hours east of Cape Town, where shark nerds from around the world come to live each year. I arrived this past June, after a long day on a small boat watching great whites chasing roped tuna heads.

��

The 2,000-pound sharks are common along the coast, which is why the property of Kenny Coskey—a laid-back local with a large house, an oil job offshore, and a close friend in the shark world—has become an ichthyologist commune of sorts.��

for your iPhone to listen to more longform titles.

A college-aged woman answered the door wearing SHARKS MAKE ME HAPPY. YOU? NOT SO MUCH. A toddler ran by with a ��toy shark. More shark-obsessed young people emerged. Most were interns with , a South African organization that specializes in tagging and studying sharks.��

My boat trip was part of Oceans Research’s side gig: conducting tests on shark repellents. Keeping sharks away from surfers and ocean swimmers as if they were mosquitoes in the woodseither through smells, magnetic fields, or any number of other schemes—has become a holy grail of sorts for a certain set of ichthyologists and entrepreneurs.

“It’s not exactly trying toothpaste on rattlesnakes,” an intern told me. “But there are easier tests to conduct.”

“I assisted an LED-light trial soon after I arrived,” one woman said over beers as rap music played. “It didn’t go well.” Great whites were wooed to the side of a 26-foot research vessel with sardines and then flashed with powerful lights while tempting tuna heads were tossed in the light’s path. The strobe had little noticeable effect; the sharks tried to eat the heads anyway.

Another tactic utilized electricity, but great whites, unlike many other species of shark, aren’t terribly bothered by it. A third used sound waves in a failed attempt to overwhelm the sharks’ senses. One group painted orca patterns on a dummy of a seal, a favorite food of whites. It seemed to work—until the dummy stopped moving. Then it got chomped.

Nothing thus far has consistently repelled the sharks. The test I was there to see, of chemicals found in decaying shark matter, commissioned by three Americans, was greeted with suspicion by the residents of the shark house.

“The ocean isn’t our home,” Gibbs Kuguru, a visiting molecular biologist in his twenties told me. “So we have to pay a tax. When the tax man calls, you pay your dues. No product is going to change that.”

While we now know a lot more about shark attacks than ever before, preventing them is still largely a mystery. Before the mid-20th century, shark repulsion was a fringe study without funding. The methods were crude. In 1916, the governor of New Jersey urged dynamiting off the state’s coast after five people were killed or maimed by a shark—either a great white or a bull—that became known as the Matawan Man-Eater. In 1945, the Japanese sank the USS Indianapolis near Guam as the ship was returning from delivering parts for the atomic bomb. Nearly 900 men died, many from shark bites. Shocked into action, the , the , and others—including Julia Child, who was then working at the Office of Strategic Services—explored chemical deterrents like cyanide and strychnine. But the chemical compounds usually just killed the sharks.

In South Africa in the 1950s, scientists stretched huge electrical cables from the shore to the surf zone and back, forming a giant U shape of presumed safety, since most sharks are sensitive to close-range electrical fields. But the cables zapped humans and washed up on beaches. Meanwhile, some Americans ventured into the sea with their legs hidden in giant plastic bags; others tried colorful bathing suits to mimic poisonous sea creatures. The sharks didn’t care.

In the 1970s, American ichthyologist Eugenie Clark found that sharks wouldn’t eat the Moses sole, a Red Sea–dwelling fish that when threatened secretes a chemical that causes the jaws of whitetip sharks to lock open. But scientists weren’t able to replicate the active molecule. A decade later, Samuel Gruber, an ichthyologist now heading the , and Kazuo Tachibana, a chemist at the , discovered similarities between the Moses sole secretion and sodium dodecyl sulphate, an ingredient in soap. Gruber built huge squirt guns to test its efficacy. It worked, but unless you shot a high concentration directly into the mouth of an oncoming shark, the ocean diluted the repellent. This was the same problem encountered earlier by Stewart Springer, a renowned shark expert who died in 1991, when he tried a mixture of copper sulfate and eosine, a purple dye.

“The reality is that the ocean is a big bunch of water,” says George Burgess, an ichthyologist who maintains the at the Florida Museum of Natural History, a collection of data going back to 1580. “Unless you have a barge of chemicals and dump shovelfuls around a guy 24/7, you won’t keep anything away.”

Worldwide each year, there are about 80 reported shark attacks, resulting in an average of six deaths. Though the odds are extremely low, fear of shark attacks remains great, which helps explain the popularity of recent films like and , as well as the sustained entrepreneurial frenzy around shark deterrents.

The most established product is a Australian device, the , that emits a three-dimensional electronic field from electrodes mounted to the base of a surfboard, supposedly causing the shark to experience muscle spasms. Detractors say it’s too pricey, too cumbersome, and unreliable. Then there’s , a $449 surf leash that sends out an electrical signal that is said to affect sharks’ sense organs. Meanwhile, a company called makes a wetsuit with a “cryptic” pattern that it claims can “hide the wearer in the water column.” And sells four-foot-long stickers that look like zebra stripes and are, according to the website, “recognized by animals through evolution to provide a warning to predators.”

“I get e-mailed once a week by somebody with a bright idea for an anti-shark measure,” Burgess says. “I have yet to see an anti-shark device that I, somebody who studies sharks and shark attacks, would plop down money for.”

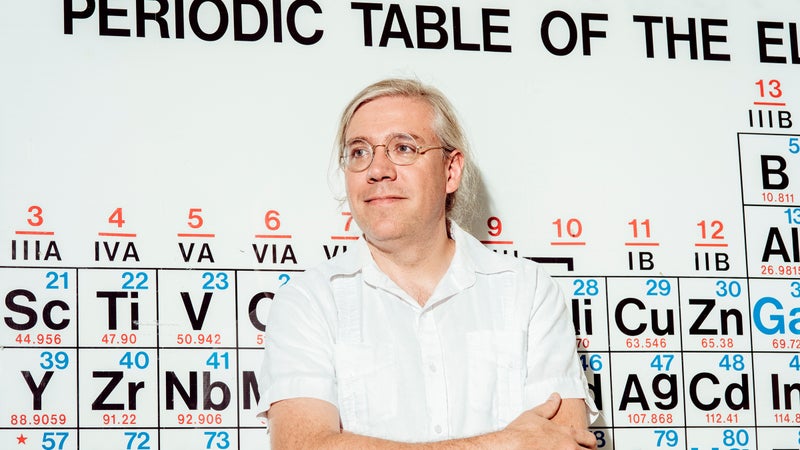

Perhaps no one has come closer to cracking the shark-repellent mystery than Eric Stroud. A pharmaceutical consultant who started his research in a baby pool in his basement in Oak Ridge, New Jersey, Stroud has spent the past 16 years studying the history and science of shark repulsion. The 43-year-old first became interested in the subject while on a cruise with his wife, in August 2001. That was when Time magazine put a great white , above the headline “Summer of the Shark.”��

“Shark attacks were on the news every single day,” Stroud recalls. “My wife asked me, ‘Where are the shark repellents?’ I looked at the literature and saw that scientists got kind of far, then stopped. I decided to delve into it, and it just consumed me.”

From 2001 to 2003, Stroud, a ponytailed and bespectacled chemist, set up inflatable swimming pools, filling them with baby nurse, wobbegong, lemon, and dogfish sharks he got from a specialty aquarium. It was a self-funded project. “Using my own little research laboratory at home, I started to study which trace compounds worked on baby sharks,” Stroud says.

“I get e-mailed once a week by somebody with a bright idea for an anti-shark measure,” says ichthyologist George Burgess. “I have yet to see an anti-shark device that I, the guy who studies sharks and shark attacks, will plop down money for.”

He first examined a group of compounds found in sea cucumbers called saponins, which were known to irritate fish gills. “I thought that if a shark got the chemical through its gill rakers, it’d be repelled,” Stroud says. Into the baby pools it went, with disappointing results. “If you handled these substances, you’d have a sneezing fit and break out in a rash,” Stroud says. “But not the sharks.”

Fortuitously, his breakthrough began when his three-foot-long lemon shark died in 2002. “I don’t know why,” Stroud says, “but I preserved it in alcohol. I didn’t want to throw the animal away. I felt really bad.”

In April 2003, Stroud went to the Bahamas to perform tests with Samuel Gruber, the Bimini Sharklab ichthyologist, who was still studying repellents. Stroud brought the saponins, as well as some of the lemon shark alcohol solution. “By then I’d heard an interesting rumor that maybe dead sharks could repel other sharks,” he says.

The saponins failed again, but the alcohol worked. “You need to study this,” Gruber told him. The vial of alcohol seemed more effective than anything else he’d tested. “It was the first time I saw something that could work,” Stroud says.

Shortly after, Stroud set up a company that is now called , received grants from the , and began studying the shark chemicals in the alcohol vial to see if they could be synthesized for commercial production.

In November 2004, Stroud dropped a magnet next to one of his tanks and discovered that sharks react to changes in the magnetic field. He tested this development with fishermen but soon found that, though it worked, hundreds of strong magnets on a metal longline vessel were not a good mix. It wasn’t the answer he was after.��

Over the next six years, Stroud largely focused on the chemical solution. Along with Patrick Rice, a marine biologist at a Florida community college, he isolated three molecules from dead sharks and tested them in the Bahamas. These compounds don’t exist in living shark tissue. They can be harvested only after aerobic decay.

“SharkDefense settled on a very specific set of aldehydes and imides we considered the ‘death signals,’ ” Stroud told me, referring to the organic compounds he replicated in a synthetic repellent. “Sharks will avoid the taste or smell of it like an evolutionary cue.”��

More important, other fish don’t mind it. “Applied to bait, our repellent can drop fishermen’s shark bycatch by 68 percent,” says Stroud. But even better than the synthetic stuff is actual rotten shark extract, which works at low concentrations. One dead adult shark, he says, will make 50 gallons of repellent and can potentially save 100 living sharks.

One way to administer Stroud’s repellent is with an aerosol can inspired by the Batman TV show from the sixties, in which Adam West uses “oceanic repellent bat spray” . Instead of spraying yourself, you depress the steel can’s button and hurl it into the water, Stroud explains, “like a grenade. The chemical comes out, and the shark leaves.” You won’t get a return—if you get one at all—for 15 minutes or more, he says. It has worked on 30 species, including bull and blacktip sharks, the two that account for the most attacks in the United States. Most promising, it exhibits what Stroud calls “broad-spectrum repellency” on most coastal sharks. An extract made from the death-signal molecules of a blue shark will repel a reef shark, for instance, and vice versa.

But as of this May, no tests had been conducted on great whites, largely due to their status as a vulnerable species. (No reliable data exists, but rough estimates put the world population at less than 5,000.) Lamnid sharks—mako, porbeagle, and great white—are fundamentally different than the coastal, or carcharhinid, sharks that respond to the repellent. Lamnids are warm-blooded, for example, and have a higher metabolism.��

“All the research has really been on the coastal sharks hitting the fishing lines,” Stroud says. “The repellent works on the two that bite most people in the U.S. But everyone thinks of Jaws, right?” Which is where those three Americans who commissioned the test in South Africa come in.��

In 2014, an entrepreneur named Nathan Garrison and his father, David, a software salesman, began testing a new product they’d come up with called , a wearable 1.5-inch-long magnet wrapped in colorful plastic. The device is based on Stroud’s research, and the duo obtained exclusive global rights to Stroud’s patent on the magnetic repulsion of sharks and stingrays. (It seemed easier to bring to market than Stroud’s still-in-progress chemical repellent.) That August, they traveled with Rice to the Bahamas to test a prototype.��

“My dad and I got in the water,” says Nathan, a 30-year-old bright-eyed surfer with a mane of blond hair, “and I filmed the scientists repelling Caribbean reef and a few blacktip sharks.” They repeated the test a few times. During each trial, the sharks clearly veered away from the bands. “There was something there,” Nathan says. “I felt confident selling it.”

A friend who worked for an ABC News affiliate in Charleston, South Carolina, produced a story on the fledgling company that September, six weeks after its website launched. The two-minute segment spread like wildfire.

“We only had a prototype, but we got all these preorders, this infusion of cash,” said Davis Mersereau, a childhood friend of Nathan’s who joined the company shortly after. “It was like doing a Kickstarter.” They had found a manufacturer in China and, by January 2015, were shipping Sharkbanz. (A fourth employee does customer service.) “I was hooked,” the 30-year-old Mersereau says. “I could immediately see the potential.”

The team asked George Burgess what he thought. “In the end, the proof is whether the product works,” Burgess told me. No one regulates the shark-repellent market, and there hasn’t been an independent study of Sharkbanz. But there have been customer trials—nearly 50,000 wristbands have sold worldwide in three years, along with several thousand magnetic surf leashes that employ the same technology.

One way to administer Stroud’s repellent is with an aerosol can inspired by the Batman TV show from the sixties, in which Adam West uses “oceanic repellent bat spray” to fend off attack.

Then, in December 2016, a shark—likely a blacktip—attacked Zack Davis, a 16-year-old in North Hutchinson Island, Florida, who was wearing a Sharkbanz wristband while surfing his backyard break. “I got it for Christmas, and the first time I wore it, I get bit,” Davis said. His arm required more than 40 stitches.

“When I saw a Sharkbanz advertisement, I thought that’d be good for my kids in the water,” Zack’s mom, Sherry, told me.

Last January, Zack Davis and Nathan Garrison appeared in a six-minute segment on Jimmy Kimmel Live. Nathan, speaking via satellite from Santa Barbara, California, told Kimmel that after the attack he’d invited Davis to “see the product in action,” from the deck of a company boat.

“He already saw the product in action!” Kimmel quipped.

“I think it’s a great reminder for all of us,” Nathan continued, “that there’s no 100 percent guarantee for any safety device.”��

The Sharkbanz team thinks that Davis fell directly onto the shark. George Burgess believes otherwise. “Davis was tumbling in the surf zone following a wipeout,” he told me. “He had the device on one arm, and the shark bit him on the other. We don’t think he landed on the shark. In our database, it’s an ‘unprovoked’ attack.”

In May, the Davis family retained Richard Hussey, a personal-injury lawyer in Fort Lauderdale. Hussey and Sherry believe the product did not work as claimed; as of press time, they are in the early investigations of filing a suit. Sharkbanz comes with a standard disclaimer stating that the “wearer assumes all risk.” And David Garrison is quick to add that “condoms, seatbelts, airbags, and helmets aren’t guaranteed to work, either. But like those, Sharkbanz reduces risk.”

Still, the Davis incident encouraged the Sharkbanz team to bring a new deterrent to market. As luck would have it, Stroud was putting the finishing touches on his synthetic death-signal repellent. The Garrisons had recently obtained global rights to Stroud’s proprietary formula and named it Sharkchemz. They decided to test it on great whites, a species they’d never seen up close, in South Africa.

Hours after my arrival in Cape Town, a once-in-a-decade storm hit the city, sending 60-mile-an-hour winds and 20-foot waves onto beaches where locals shot cell-phone videos and skimboarded across the flooded sand. The next day wildfires raged, eventually killing at least seven people and forcing the evacuation of 10,000 more near our route to Mossel Bay. Meanwhile, Nathan Garrison had an allergic reaction to something he ate, requiring a visit to a remote medical clinic.

“When it comes to shark research, nothing is easy,” David said while driving to the test site with four gallons of Stroud’s shark repellent sloshing around in the back.

“He’s right,” added Mersereau. “One time, while testing in the Bahamas, the whole island we were on ran out of gas.”

Nathan’s rash cleared up, and we detoured to Jeffreys Bay, a few hours beyond Mossel Bay, to surf. Arriving late, we saw the bay’s famous waves for the first time in full, fantastical moonlight. The next morning, Mersereau read a news story about an American woman who lost an arm to a tiger shark while snorkeling in the Bahamas.

“Super sad,” he said. “Bet this is gonna go viral.”

Down at the beach, Nathan took a better look at the break where professional surfer Mick Fanning encountered a shark—likely a great white—while competing in the 2015 Jeffreys Bay Open. The waves were pumping, and Nathan stayed out for three hours. When he finally came in, he said it was the best surf of his life.��

“I saw two kids wearing Sharkbanz,” he said. “But we were too busy ripping to talk.”

Later that afternoon, he and Mersereau walked into the sprawling Jeffreys Bay offices of Cheron Kraak, co-owner of the surf shop . Kraak explained how she had a bad experience with another shark-repulsion product she’d put on her shelves some years prior. It was expensive and didn’t seem to work. Few of them sold. She was skeptical that any product could stop a great white, or as she put it, “a double-decker bus.”

“We wasted a lot of money on… what was it called?” she asked a nearby assistant, who reminded her of a company, now defunct, that sold a surf leash that emitted an electrical field.��

“The product was really bad,” Kraak said. “Wouldn’t even stay charged.”

Garrison nodded. “What we do is totally different,” he said. “It doesn’t need any charging or batteries.”

He showed her a Sharkbanz wristband and explained how it works.��

“Sharks detect magnetic fields,” he said. He told her the price, , and they discussed how to minimize the duties imposed on imports to South Africa. Kraak was interested in becoming a distributor, potentially the first for Sharkbanz in South Africa. Stoked, the three men headed to Mossel Bay for the primary purpose of the trip.��

“It’s time to see our first whites,” David said. “The quest resumes.”

We’re finally on the boat just off Seal Island, a speck of land less than a half-mile from shore. It’s time to infuse the sea with a liter of Sharkchemz, which has been stored in a Mott’s apple-juice jug that cleared South African customs without a second look (though the team did have permits for the solution).

Nathan removes the cap and the repellent seizes the air around us, which is already perfumed by a trash can full of sardine chum and the excretions of a thousand bleating seals. The collective aroma conjures “horse shit in rotten clam chowder,” says Nathan. “A sea lion locker room,” Mersereau adds. But Enrico Gennari seems unbothered as he mashes sardines with a wooden pole at the stern, wearing a horned cap and more facial piercings than most scientists.

Having seen many repellents fail, Gennari is a realist. “The white is a very peculiar shark,” he tells me, shrugging. “They do what they want.”

“Pirate money,” he says, pointing to the rings in his eyebrows and ears.

Gennari is the 40-year-old Italian tasked with testing the stuff. He gives orders to two assistants, as well as the surrounding sharks, in a thick Roman accent.��

“Spit it out, dumbass,” Gennari says to a shark that seizes a tuna head. Then he turns to me. “See where you stand? A three-meter white shark breached and landed there a few years ago.”��

He ladles more chum, like spaghetti sauce, into the chop. More sharks begin circling and lunging for the tuna heads, which are being dragged across the surface by one of Gennari’s assistants.

“There’s a surf break over there,” Gennari says, pointing less than a mile away. “I don’t surf it. I know what is beneath.”

He spots a ten-foot monster. “I think that’s ABC,” he says. Gennari and his team have named many of the sharks they see regularly. There’s Nubs, Ghost, and Sharky McSharkface. They’re identified by physical traits: a black line on a dorsal fin, gills with parasite scars, a white nose patch.

Gennari came to South Africa 12 years ago and received his Ph.D. in ichthyology before cofounding Oceans Research. Testing repellents for private companies, which Gennari does once or twice a year, helps pay for things like Oceans’ long-term effort to tag and track all the whites in Mossel Bay. David paid Gennari around $5,000 for today’s preliminary testing of Sharkchemz and would likely pay four times as much for a full trial if an independent analysis of the results seemed positive.

Having seen many repellents fail, Gennari is a realist. “The white is a very peculiar shark,” he tells me, shrugging. “They do what they want.”

Once enough sharks have congregated around the boat and shown interest in the bait, Gennari begins the testing. Using a bilge pump, he sends a liter of the chemical solution from the Mott’s bottle through a tube attached to a long stick and into the water about eight feet from the boat. A ripe canister of sardines also dangles at the end of the stick. The first few sharks approach the bait but turn away. Then, after four minutes or so—enough time to provoke optimistic glances—a giant shark takes the canister deep into the sea. A storm soon forces us back to the harbor. The next day, the tests resume with much the same result: a short period of absence followed by largely normal alpha-predator behavior.

“This is quite good for a normal tagging trip,” Gennari says after we’ve seen some 30 different sharks. “But for a repellent trip, maybe not so good.” In any case, many more trials will need to be undertaken.

“Inconclusive,” says Gennari.��

“Back to the drawing board,” says Mersereau.

The morning of the final test, Nathan goes surfing while Mersereau, David, and I take turns diving with the sharks, protected by a small cage and a Sharkbanz wristband. As the lid clanks closed above me, I try to catch my breath and grab the sides for leverage, endeavoring to keep fingers and toes within its aluminum bars. I can see only a few yards in front of me. No sharks charge or bite the cage. But the nearby rotting tuna heads are surely more appealing than my wetsuit-encased flesh. This is not a scientific test, just more grist for hopeful speculation.

After a few minutes, gaping jaws appear out of the nothingness. A 14-foot shark surges toward the tuna, its eyes rolling back in its head. Then it disappears. Soon another beast emerges. Then I seem to be alone.

After ten minutes, I signal to one of Gennari’s assistants to open the cage and then I jump back onto the boat. It’s Mersereau’s turn. He’s certainly no wimp, but he taps out after 30 seconds in the cage. “I had a moment in there,” he says. “And I didn’t even see a shark.”

Charles Bethea () wrote about letsrun.com in the December 2016 issue.