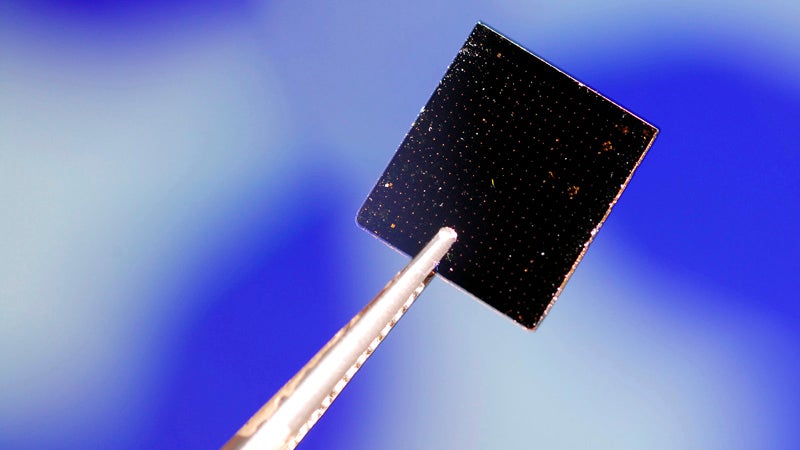

What do the condom of the future and the new line of women’s skis from Head have in common? Okay, you’re not gonna get this one, so I’ll just tell you. Both will utilize a material called graphene, a layer of carbon atoms bonded together in repeating hexagonal shapes. One million times thinner than paper and 100 times stronger than steel, graphene is considered the strongest and lightest material known to man.

Two scientists from England’s University of Manchester discovered graphene in 2004. They were subsequently awarded the 2010 Nobel Prize in physics for isolating the material. Since its discovery, graphene has been imagined for numerous applications—everything from unbreakable phone screens to body armor for soldiers to better solar cells (the material is an excellent conductor of heat).

A University of Michigan study is looking at how graphene could be used to make infrared contact lenses. And that condom, which the University of Manchester is developing thanks to a $100,000 grant from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, is supposed to be the strongest and thinnest condom ever made—and therefore a condom men might actually be inclined to wear because of the near-normal sensation the prophylactic will allow. (When I tried to reach somebody at University of Manchester for comment, I was told nobody was available.) The Polish government is so encouraged by graphene’s potential that it has poured nearly $70 million into infrastructure to produce the material.

One million times thinner than paper and 100 times stronger than steel, graphene is considered the strongest and lightest material known to man.

Any real use for graphene so far has come in the world of sports. Last year, Austrian sporting goods manufacturer Head increased the power and control of its tennis racket by employing graphene in its throat. In testing, the manufacturer noticed that the most precise and hardest-hit balls were struck using rackets that were light in the midsection but heavy in the handle and head. The prototypes, however, kept cracking. Graphene solved that problem.

Catlike, a , is also using graphene to make lighter and more durable helmets. The four styles of , which the company claims are incredibly strong yet incredibly lightweight, have been on the market only for a few months and cost around $300.

Next season, Head’s line of women’s skis will feature the material. “Graphene allowed us to target where we wanted to reduce weight while also increasing the product’s strength,” says Jon Rucker, Head’s vice president.

In the groomer ski category, the company used graphene in the midsection, allowing the heavier tip and tail of the ski to grip the snow. In powder boards, Head designers used graphene in the tip and tail to allow the ski to float through the fluff.

The downside to all this is that the skis are more expensive. Graphene costs about 20 percent more than fiberglass or carbon, other materials used in ski manufacturing. That means Head’s Total Joy, which is 85 millimeters underfoot, will run you about $1,000.

If reports are true—that the skis are damp, strong, and lighter than other skis on the market—then the cost may be worth it. Head also plans to unveil men’s skis featuring graphene. “There’s no timetable,” says Rucker. “But they’re coming.”

Other sporting goods products featuring graphene may also be on the very near horizon. “If graphene isn’t manufactured perfectly, the material is weak,” says Jun Lou, a researcher at Rice University who recently released a study on the effectiveness of graphene. “But if it’s mixed with other materials in a composite, as would probably be the case in most sports equipment, the product will likely do very well. It’s also a cheaper way of using graphene, so I think we’ll see more of that soon.”