What the World Needs Now Is Clothing Made for Mars

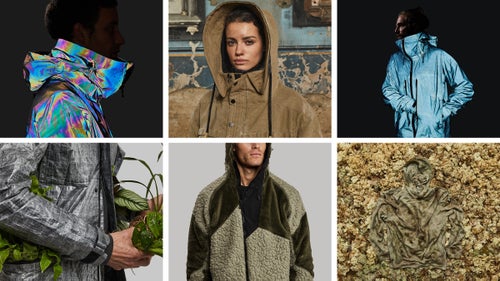

With fabrics created from alga, graphene, and copper, and hoodies built to last a hundred years, two British ad men are creating the apparel and gear of the future

New perk: Easily find new routes and hidden gems, upcoming running events, and more near you. Your weekly Local Running Newsletter has everything you need to lace up! .

The first piece of Vollebak clothing I ever held in my hands was the planet earth hoodie, which landed on my New York City doorstep in late February 2020. The 30-person company was founded in London in 2015 by twin brothers Steve and Nick Tidball, who’d come from the world of advertising and displayed a penchant for highly technical, highly conceptual adventure clothing. The brand is small—“We’re not going to give Nike any sleepless nights,” Steve said—so the brothers rely on fervent word of mouth and offbeat marketing. In 2019, for example, to launch their incredibly niche Deep Sleep Cocoon—a “self-contained microhabitat” to help the wearer shut out the noisy world of long-haul space flight—they rented a billboard across the street from SpaceX, in Hawthorne, California, that read: “Our jacket is ready. How is your rocket going?” (No response from SpaceX founder Elon Musk, but the brothers said that they did get an invitation from NASA to give a talk.)

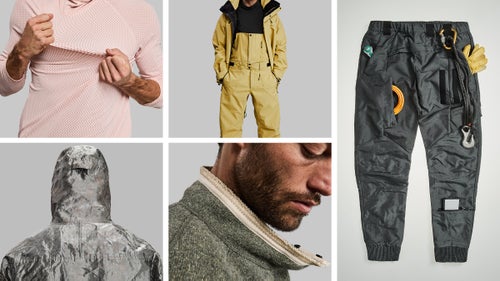

The Planet Earth hoodie, made from Australian merino wool with a brushed-fleece interior, struck me as well-made and comfortable, if hardly revolutionary in a world swimming with hoodies. There was one detail, however, that stood out: a hinged merino face guard of sorts, with small ventilation holes. “From NASA space helmets to explorers’ balaclavas,” read the company’s description, “protecting your face and head has always been high up on the list of priorities for people on a mission.” Fair enough, I thought, even if my “mission” rarely went beyond typing at my laptop.

And then, a few weeks later, the pandemic struck. Suddenly, the idea of covering one’s face no longer seemed extreme. Like most everyone, I spent a not insignificant portion of the next two years behind a mask. And at the height of the pandemic, when the sound of sirens filled my Brooklyn neighborhood, I often found myself throwing on my Planet Earth hoodie and pulling up the merino visor over my N95 for an added layer of protection. What I’d first dismissed as folly now seemed eerily prescient.

Flash forward nearly two years and I’m in the cozy Vollebak offices near the Soho section of London, hovering around a conference table with Steve and Nick, admiring their latest piece of space-inspired clothing, the Mars jacket. Sleek and shiny, it looks plucked from the set of Dune. The company describes it as “industrial workwear fit for any planet.” Nick, who trained as an architect and handles the design work, excitedly points out the details. It is made from ballistic nylon to resist the corrosive effects of space dust. There’s an abundance of Velcro straps, “a gravity surrogate in space,” he says. And there’s a 3D-printed “vomit pocket” containing an orange PVC sack, should you suffer space-adaptation syndrome, a type of motion sickness. “The vomit bags are really beautiful,” he says. They’re designed with large deployment tabs and are brightly colored because, he notes, “when you’re puking, your eyesight’s crap and the vomit bag has to be really, really recognizable.”

Steve, who sees to the company’s sales strategy, admits that the actual functional market for Mars clothing is precisely zero. “But the idea is, we’re probably not going there for 30 years,” he says. “If we’ve been designing clothes for Mars for 30 years, testing them on earth, I’ll reckon we’ve got a good shot at making decent clothes for Mars.” Not everyone who goes, he says, will be “a Russian cosmonaut who’s been training for 20 years.” Instead, he says, it will be regular people with regular human needs who won’t want to live in a space suit 24/7.

“No one,” he says, “has asked us to do this.”