On June 22, the Tokyo 2020 Organizing Committee for possible inclusion in the 2020 Olympic Games in Japan.* While chess, tug of war, and Frisbee, among others, didn’t make the cut, surfing finally did.

Following the committee's decision, the president of the International Surfing Association (or ISA, surfing's governing body), Fernando Aguerre, , “This is a significant milestone for our sport and gives us further motivation and resolve to make our Olympic dream become a reality.” Aguerre has led a decades-long crusade to get surfing into the Olympics. Now that he’s closer than ever, you’d think surfers the world over would be rejoicing along with him. But they’re not—for many reasons, some dubious and others perfectly valid.

Australian pro surfer Owen Wright, who had just won the Volcom Fiji Pro, told Reuters the day after the IOC announcement: “I think surfing in itself is more of an art form and an expression. The Olympic banner doesn’t really suit the sport.”

From a distance, it might seem Wright’s is some kind of fringe opinion, not to mention a little hypocritical, considering that he competes professionally in the World Surf League (WSL). But dare to dip a toe into the pro surfing scene and you will discover that competitors and fans alike have a long history of resisting Olympic recognition. The reason has a lot to do with surfers’ perennial fear of loosing what they call their “core status.”

In 2011, the author of The History of Surfing, Matt Warshaw, told Surfer Magazine, “The thought of surfing in the Olympics brings a familiar dab of bile to my throat.” Curious to know if his mind had changed since the IOC’s announcement, I contacted Warshaw this week. “Surfing in the Olympics, it’s like teaching a cat to use the toilet,” he told me. “It’s a novelty, at best.”

Warshaw, by his own admission, is holding on to the bygone idea that surfing “lives in its own little funky beautiful cul-de-sac in the world of sport.” As a lifelong surfer, I appreciate Warshaw’s sentiment, and I too yearn for the preservation of surfing’s funky beauty. But the truth is, the funk is dead. Surfing has plunged into the mainstream.

The WSL’s current title sponsor is Samsung. Most major surf apparel companies are publicly traded, multi-national corporations. Nick Woodman, who founded GoPro because he wanted to film himself surfing, is worth $2.4 billion. Take a walk through New York City or Tokyo and just try not to notice all the surf inspired clothing in the windows of fashion boutiques. Chess, tug of war, and Frisbee are not exactly garnering that kind of “youth appeal,” which was “key characteristics” the Tokyo Organising Committee was looking for in the twenty-six long-listed international federations that sought inclusion as additional events in the 2020 Games.

For all the pushback from surfers, bringing surfing to the Olympics isn't going to tarnish the meditative art of soul surfing. There is, however, one big problem with including surfing in the Olympics: surfers sometimes get skunked. There is no more unpredictable playing field than the ocean, especially in Japan, a country not known to produce the kind of large, crowd-pleasing waves found in places like Hawaii, Tahiti, or Fiji. Anyone who has had the great displeasure of visiting the U.S. Open of Surfing in Huntington Beach on a scorching, wave-less summer day, and witnessing surfers compete in wind-shorn, two-foot surf, will know how boring professional surfing can sometimes be. The WSL handles this problem by opening weeks-long windows in which contests can be held, rather than assigning them a specific date in advance, and surfers simply wait for contest-worthy waves to materialize before competing. (Even then, the waves don’t always arrive, and contests have been run in sub-par conditions.) But with live television schedules to contend with, such waiting periods may not be an option in the Olympics.

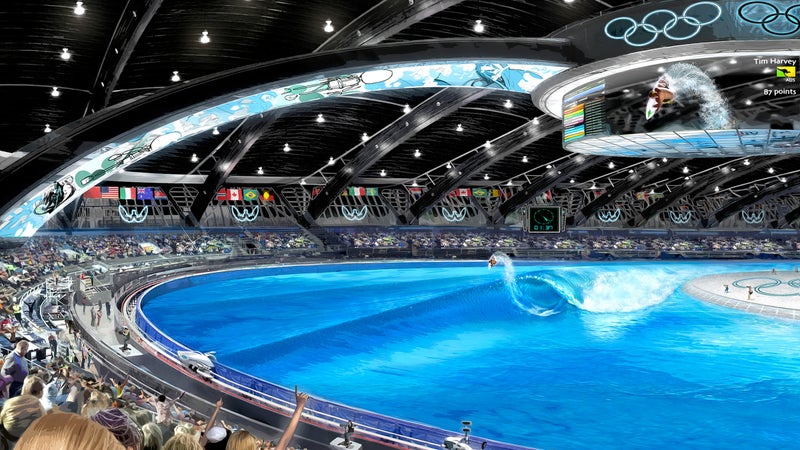

Aguerre and the ISA have thought of this, and their solution to the ocean’s inconsistency is the promising advent of the wave pool. It's basically a massive swimming pool in which quality surfing waves are manufactured to provide a near static medium, much like a half-pipe, for surfers to compete on.

“Once people understand better that we will be running competitions on high quality artificial waves, I think a lot of attitudes will change,” Aguerre told me. “And just like the [1998 Nagano] Winter Olympic Games did for snowboarding in terms of elevating the athletes and sport without sacrificing their core identity, I think most people will come around to the same realization [with surfing] in the Summer Games.”

While functioning wave pools were once a topic for those science-fiction geeks among the surfing populace, today they are as real as corporate suits running the surf industry. From in the UAE to in Wales, which is set to open next month, the technology to produce barreling, head-high waves that break for the length of a football field has arrived. The pools themselves are for much of the same reasons why surfing in the Olympics is: they're viewed as impure. But with the dawn of world-class artificial waves on the horizon, protests against wave pools may soon be moot. Even Kelly Slater, the greatest surfer of all time, has in the wave tech game.

And anyway, isn’t it time for us old salts to shelf our nostalgia for the sake of the children? The current world champion, 21-year-old Gabriel Medina, told me last year that it would be a dream come true to represent his native Brazil on the Olympic stage. With an estimated 35 million people riding waves around the world these days, there’s no denying surfing is a sporting force to be reckoned with. Why not give the thousands of talented young surfers with Olympic dreams the chance to express their art form, be it in salt or chlorinated water?

Those sports selected for inclusion in the 2020 Games will be announced during the 2016 Summer Olympics in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

*Correction: A previous version of this article incorrectly stated that the International Olympic Committee had shortlisted surfing.