“The desire and intention to make photographs sometimes overpowers the truth in them,” James Fee says, seated at his home in Los Angeles. “The snapshot, for me, has always held more truth than professional photography.”

River of Sorrows Slide Show

to see more of James Fee’s images, and hear him talk about photographing the Dolores River.Dolores River photography

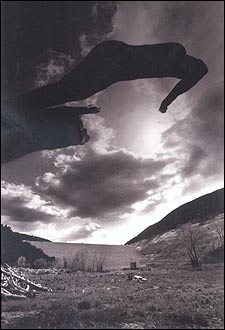

The dammed Dolores River

The dammed Dolores River

Given that Fee is a renowned photographer best known for his dark, somewhat ominously styled compositions, his comments are a little surprising. But flipping through the collection of photos he took for �����ԹϺ���‘s June feature article, “Dry Run on the River of Sorrows,” one begins to see what he means.

In April 2003, �����ԹϺ��� sent Fee, 54, to photograph Colorado’s Dolores River for that story, written by Mark Sundeen, as part of a series of articles exploring America’s use and misuse of water. Fee seemed the perfect fit. His penchant for moody imagery seemed appropriate to the bleak condition of the Dolores, whose seasonal flow has been nearly sapped dry from years of drought, agricultural use, and damming.

Unlike other landscape photographers who favor shooting placid glacial lakes or imposing mountains, Fee is not a photographer interested in taking “pretty” pictures. Instead, he uses his camera as a critical eye to explore societal and environmental problems. “It’s a political landscape for me, not necessarily a beauty landscape,” he says. “I think that most landscape photography of our environment has really been an effort to glorify it in some way, to accentuate the beauty of being outside. My view has always been really different.”

“Dry Run on the River of Sorrows” chronicles Sundeen’s attempt to raft and kayak the Dolores, which was once a favorite of whitewater lovers but is now so low in spots that it can barely float a toy boat. But Fee left the paddling to the writer—in fact, he didn’t even set foot in a boat. Instead, along with river guide Thomas Klema and a photo assistant (who briefly and unsuccessfully attempted to raft the river), Fee followed the Dolores by foot, car, and plane from her headwaters near Colorado’s San Juan Mountains toward her confluence with the Colorado River in Utah.

Prior to this assignment, Fee had never visited the Dolores, and he intentionally avoided researching the river. He wanted to shoot with as few preconceptions as possible—which included not asking Klema too many questions. Instead, Fee set about discovering the river through his lens. “Mostly I wanted to work my own way through the project without too much information,” says Fee. “I tend to do my best work with things I know less about. A lot of times, that fresh view of not knowing exactly what’s going on and allowing the camera to do the exploratory process is much more beneficial.”

During the shoot, Fee and his companions found that the Dolores had been “bled dry” in many spots. But Fee’s exploratory eye moved beyond the flow of the river to the trash, junked cars, and radioactive-waste warnings littered along the riverbanks. His attention to such details is not surprising. After all, for much of his work, Fee’s muse seems to be the underbelly of America: an ironically beautiful land of abandoned and crumbling factories, murky forests, and people at the fringes of society. In the end, though, the Dolores project did toss Fee a surprise about his own photography: the truthful nature of the snapshot.

Throughout the trip, Fee took the melancholy black-and-white photos he’s best known for as well as a series of simple, color snapshots to record shot locations around the Dolores. He didn’t think much of the snapshots until he learned that �����ԹϺ��� wanted to use them for most of the piece. At first Fee was surprised—he’d taken the snapshots quickly and without much thought, mainly for positioning his more composed photos. But after looking through the collection he realized that “the story wasn’t so much in the photographs that I was trying to ‘make,’ as it was in the positioning shots. There’s much more truth in those photographs than the ones I was trying to interpret.”

“I really shot two visions of the river on this assignment,” Fee said, “a more positive vision and a more negative vision.” His negative vision, the composed black-and-white shots, ultimately seemed less truthful to him than the direct statements made by the snapshots.

Though the Dolores River project hasn’t changed Fee’s rather critical view of the American landscape, the experience did give him a new perspective. “Your own ideas are always getting in the way of the simple process of making photographs and that’s why snapshots are so honest,” he says. Fee plans to integrate some snapshots into his newest collection, What We Saw, which will feature photos from Burma, Italy, and Costa Rica, as well as the Dolores River.

“Photography, for me, is a tool of communication and a tool of change.” Fee says. “The quickest way to get things moving and to change things is to go right to the heart of the problem and so I tend to focus on what’s wrong with our environment, what’s happening that we should change.”