I SKIPPED A LOT OF CLASSES IN HIGH SCHOOL, so it wasn’t until our soot-streaked Mi-8 helicopter slipped down into the northernmost valley of outermost Mongolia and began whirring us above the Uur River at little more than treetop level that I finally caught up with Hemingway 101.

Fly-Fishing Mongolia

TEASING THE MONSTER: Guide Dan Vermillion, left, mans the landing net while The author works a Chernobyl squirrel over a stretch of the Uur

TEASING THE MONSTER: Guide Dan Vermillion, left, mans the landing net while The author works a Chernobyl squirrel over a stretch of the UurFly-Fishing Mongolia

Fly-Fishing Mongolia

FAITH-BASED CONSERVATION: local mongolians, who work with fishermen and scientists to protect the Eg-Uur watersheed, visit anglers in camp

FAITH-BASED CONSERVATION: local mongolians, who work with fishermen and scientists to protect the Eg-Uur watersheed, visit anglers in campFly-Fishing Mongolia

“YOU’RE GONNA CATCH A BIG ONE”: guide Charlie Conn waves fishermen luck as they head out before the Uur’s first snows

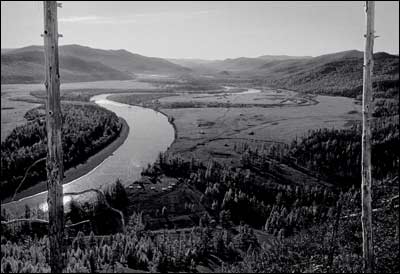

“YOU’RE GONNA CATCH A BIG ONE”: guide Charlie Conn waves fishermen luck as they head out before the Uur’s first snowsFor three hours, I had been glued to a porthole, watching the wrinkled autumn skin of the earth unveil itself as we flew north, over open desert, into rolling plains, and out toward the Russian border. Each range of hills was steeper than the last, and finally some trees—Siberian larch and pine—began to appear. When we dropped toward the last valley, I saw, flashing below us at a hundred miles an hour, the telltale black circles and twisted thickets left by a forest fire. The fire had been out for several years, but long stretches of gray hillside and tangles of stripped trunks revealed its former rage.

Over the summer I’d been on a sort of literary crack binge, hiding in the cool aisles of library stacks with all the Hemingway stories I was supposed to have read decades ago. But only now, from the Olympian vantage of a Russian helicopter, did I abruptly comprehend one of his most obvious metaphors. The cold fire down below was the same ash-strewn wreckage that greets Nick Adams in the opening sentence of “Big Two-Hearted River,” perhaps the prototype for all American fishing tales. In this 1925 story, Adams walks out of that burn, away from his nameless anxieties, carrying a fly rod. Going into the wilderness of Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, he finds his “good place,” a section of pine forest beside a river marbled with trout. Once the tent was up, “nothing could touch him.”

I was having a busy month of discoveries. A late bloomer, I’d gotten married three weeks earlier, my first time on that journey. And now here I was making my first trip to Mongolia, to catch my first taimen, one of the world’s most elusive freshwater fish. A massive salmonid once common from Bohemia to Hokkaido, the taimen is making one of its last stands here, in the high, cold, pure rivers of Mongolia’s remote watersheds. This rare opportunity is what filled the helicopter with Texas businessmen, doctors, and millionaire factory owners, as well as two New Yorkers: me and James Nachtwey, a legendary globe-trotting photographer for Time. We were all here to catch a big fish, maybe the fish of a lifetime.

This was also, unaccountably, my first flight in a helicopter. On the tarmac in Ulan Bator, Mongolia’s capital, I had asked Jim for advice. He’d been flying in helicopters for decades, whisking in and out of war zones. Although he didn’t say so, Jim had been in Darfur the week before, and the next week, no doubt, it would be some other terrible place. In War Photographer, a 2001 documentary about his career, Jim was shown calmly snapping away in burning Balkan villages and shootouts in Palestine. His terrifying pictures from September 11, taken at the feet of the twin towers, open the book War, a collaboration of the nine photographers in his agency. Living two miles from ground zero, I only felt like the north tower had fallen on my head; in Jim’s case, it nearly had. Despite all this—or perhaps because of it—he had a boyish enthusiasm for adventures like this one, for the innocence of chasing wild fish in wild places. And he loved helicopters.

“They are magic carpets,” Jim said, with his usual grin. Jim is a man of few words, and his advice was to the point. “Pee before getting in,” he said—there were no toilets. For once, a useful tip.

When we landed and began to unpack, I could not contain my idiotic enthusiasm for my recent discoveries in the field of American literature. I told Jim how I had finally realized, while riding in the Mi-8, that the burned forest in the opening of “Big Two-Hearted Riv—”

“It was the war,” Jim interrupted, not looking up from his duffel bag. He kept unpiling his clothes, sorting the fishing gear from the fleece and the socks.

“The fire was the war,” he said.

MONGOLIA IS a land of brutal superlatives. With a mean temperature of 28 degrees, Ulan Bator, known as “U.B.,” really is the coldest capital in the world. And with fewer than five people per square mile, Mongolia actually does have the lowest population density of any country. Despite a tourism boom—up 50 percent just last year—and a gold-mining rush, half its citizens are still nomadic, husbanding animals over vast spaces of desert and foothill. The place is a synonym for emptiness, the thing beyond the beyond.

Perfect fishing country, in other words. The helicopter had dropped off the Texas doctors in a lower camp, and we were set down 60 miles to the north. This camp, run by a Montana company, Sweetwater Travel, was on the banks of the Uur River, which drains the high timber country east of Lake Hovsgol, Mongolia’s biggest, and flows down into the Eg River and eventually on to Lake Baikal, in Russia. The small encampment included five gers, the traditional Mongolian tents of thick felt laid over a round frame of willow switches.

There was also a log cabin for dining, and on that late-September night, over a dinner of Mongolian noodles with beef, we met our fellow elect. The guides were both Montanans. Dan Vermillion was a Livingston lawyer who had abandoned the bar to open these waters to catch-and-release fly-fishing a few years ago with his brothers and a Mongolian partner. Charlie Conn was the Candide of the Rockies; upon meeting me he announced that I was about to catch a big taimen and never deviated from that faith. His cowgirl wife, Wendy, had flown in with us, as had Bill and Sharon Sumner, irrepressible Texans in their mid-fifties. Sharon proved to be a sharp caster, with a game attitude and a balanced personality, which was vital, given that her husband was an angling maniac. Between stints rescuing his plastic-bag factory from one crisis or another, he fished all over the world. He’d tried to break the addiction with golf or hunting, but nothing else worked. Taimen have been known to burst out of the water to swallow prairie dogs neat. Bill had come all the way to Mongolia to see if the world’s biggest freshwater salmonid would sate his fish lust once and for all.

Bill wasn’t just from Texas; he was from TEXAS. He liked speaking loud, and he liked speaking his mind. About five seconds after we sat down to eat, he asked Nachtwey the question I’d been trying to avoid all day.

“SO, JIM,” he bellowed. “I HEARD YOU GOT BLOWED UP IN EYE-RACK. WHAT HAPPENED?”

THE FIRST DAY OF FISHING WAS SWEET, which should have been a warning. We rolled out in two green johnboats and were soon in warm sunshine along open, sweeping bends in the river. The Uur came out of a canyon here, fast, and made a deep cut into the valley floor. Jim hooked up on his third cast.

In no time he held a thrashing monster in the shallows. It was a mottled, flashing gray and had a disturbingly prehistoric look to it, with a wide mouth, supermodel lips, and rows of sharp-looking teeth. We netted it and photographed it, and I measured it at 36 inches. This wasn’t quite one of the legendary fish of the Uur, but it was big enough that Jim had trouble holding it out of the water when Dan Vermillion reached in with a blue plastic rivet gun and drove a numbered tag through the dorsal fin. Part of Sweetwater’s catch-and-release regimen involves tagging and tracking the taimen, to fill in the gaps about their habits.

Dan used a fishing technique called drop-dragging, which means floating downstream with an anchor tied behind the boat. Taimen fishing requires long, languid casts, each one covering as much water as possible, and slowing the boat helps. We were tossing five-inch poppers with sparkling tails, which landed like old sneakers and threw a wake that screamed Eat me! halfway across the valley.

Cast. Cast. Cast. Then cast some more. We’d been warned, repeatedly, that taimen are finicky creatures, hard to find and harder to catch. I’d made 150 casts by lunch, without hooking a thing. In the afternoon the temperature dropped to the forties and the wind picked up. Hurling Chernobyl squirrels into this gale was futile, swinging the heavy rods and lines a sustained torture.

But once you’ve seen a photograph of a man holding a fish the size of a golden retriever, you believe you will catch one that big yourself. On subsequent days, even Charlie’s genetic optimism (“This is the cast… OK, I can feel it this time…”) wasn’t enough to summon the taimen. Twenty-inch lenok, a kind of proto-trout, were there for the taking, but we foolishly ignored them in our relentless hunt for taimen.

Each day the lower reaches of the forest were gilded with more defectors to autumn, and the upper watershed was soon a golden brocade woven tightly around the last green holdouts. We experienced all the side effects of wilderness fishing: the ice-cold water down the back of your underpants; the split thumbs; dogs howling all night at the wolves; the frosty kiss of an outhouse seat at 4 a.m. Jim and I hit the boat at dawn, fished hard all morning and then all afternoon, floating or afoot.

“Man, this is melancholy,” Jim volunteered one afternoon, from a hunched position in the bottom of the boat, ice coating his boots. For one of the world’s foremost combat photographers, that’s really saying something.

People expect photojournalists to twitch and freak, Dennis Hoppers of the Apocalypse. But 25 years of covering wars had honed Jim rather than deformed him, stripping away the unnecessary and removing the neurotic. He was full of self-control, a drinker of club soda who listened carefully and looked where he stepped. War had rubbed him down into one of the most serene and sane men I’ve ever met.

In the log cabin that first night, when Big Bill demanded the story of what had happened in Baghdad, Jim had paused for a long moment. Then he gave a barren answer. With all the guides and clients leaning forward, he said, in a monotone, that someone had thrown a grenade into the Hummer he was riding in. He had taken some shrapnel in the knee. The Time writer with him had lost his hand. The two soldiers had been discharged for their injuries.

Everyone sat there, waiting for the rest of the story. But that was it. Twenty seconds. Just the facts. Jim was a terrible storyteller, probably on purpose. He spoke with his camera.

When we were alone, hiking one day, Jim did finish the Baghdad story. But it was comedy, not tragedy. He fell into giggles as he related the fallout of that night. Bleeding and stunned, he’d been evacuated to an American medical unit. But while doctors cut the shrapnel not just from his knee but from his leg, stomach, face, hand, and groin, someone had stolen his wallet. It took Jim six months to replace all the contents. “That’s the only thing that really bothered me,” he said, laughing at himself. Blown up by the enemy and then robbed by your own side.

The attack had real consequences. Jim had been laid up for months and still carried a satchel full of medications. Half a year later, he was once again agile as a goat, ready to cover tsunamis and slow-moving social catastrophes. But he couldn’t run, and that meant no more assignments to the front lines for the time being. “There hasn’t been a war yet where I didn’t have to run,” he said.

I’d had to run for it a few times myself. For more than a decade I’d covered insurgencies in Colombia, Cambodia, Nepal, and Afghanistan, always at boot level, among the peasant fighters and mad Marxists. I’d grown tired of tear gas and heavily armed teenagers, of having my sources arrested or, in one case, killed, of walking into minefields and tangling with mobs. And yet I’d only glimpsed, as through a curtain, the world where Jim lives almost without pause.

This peripatetic life doesn’t lend itself to long-term personal relationships, so, like Nick Adams, I’d begun to walk out of my own burned past, searching, in wilderness and family, for that elusive “good place.” I was settling down. In the boat one day, I told Jim about my recent wedding and the fact that my wife was secretly pregnant. We hadn’t told anyone, not even our parents, because there had been a miscarriage earlier in the year.

“How old were you when you got married?” Jim asked.

“Forty,” I said. Jim is 57, and still a bachelor.

“So,” he said. “There’s hope for me.”

Later, as we drop-dragged through a slow, emerald section of the river, he let slip why he was here. We weren’t catching anything, and I was in a black mood, but Jim sailed along, sublimely happy. After yet another cast to a promising spot that produced nothing, he said, “That’s why I like fishing. You have this sense of hope.” Each cast was a flick toward possibility. A blank slate.

“Palpable hope,” he said.

WE ATE LUNCH SOMETIMES in a broad meadow, speckled with horses and the ruins of a Buddhist monastery. Dan Vermillion was working with the Tributary Fund, a Montana-based nonprofit devoted to protecting native species by collaborating with indigenous cultures. A local monk, perhaps mindful of the fund’s contribution to rebuilding the Dayan Derkh monastery, had ruled that Buddhist sutras condemning the unnecessary harming of animals might be relaxed for catch-and-release fishing if the sport could help protect the species.

Dan was hoping that a Buddhist endorsement would do more than justify a sport fishery. Mongolia’s rivers are salted with flakes of alluvial gold, and one mine using cyanide extraction was already operating within earshot of the Uur. There was also proposed placer mining, which would involve ripping up the entire streambed, wiping out the taimen and much else. A “faith-based conservation” movement, as Dan called it, was crucial to stopping the mines and, more important, stopping taimen poaching by Chinese and Russian meat fishermen. Foreigners, too, were having outbreaks of faith. One grateful angler had sent a check for $25,000 to the Tributary Fund; after my visit, the same client contributed another $150,000.

Upstream one afternoon, I hauled in two 20-inch baby taimen in quick succession, and looked up to see Jim waving at me from the far bank. Dan picked me up in the boat and we went over to find Jim paused over a set of bear tracks in the sand.

“Siberian brown bear,” Dan said as we slowly followed the paw prints up from the water’s edge, across a beach, and down into a tributary stream. “He better watch out,” Dan said. The tracks were heading out of the Uur Valley, toward human settlements. The bear would get shot there and sold in parts for black-market medicine and trophies.

With the Tributary Fund, Dan had arranged for field scientists from the University of Wisconsin and the University of Nevada–Reno to monitor the taimen. Protecting this paradise required some proof of the value of these fish, of the size of their population, of their migration patterns and appeal to sportfishermen. The scientists had their own ger camp a half-mile from ours and were busy putting radio transmitters into the bellies of captured fish—anesthetizing the taimen, slicing them open, and suturing them back tight. They named each fish before releasing it, so that the river was now dotted with radio-beeping taimen named Snoop Dogg, Pumpkin, and—the very largest, a five-footer weighing in at around 100 pounds—Anna Nicole. We fishermen had a small role to play; in addition to tagging our catches, Dan had volunteered us as fish herders.

That’s how I found myself drinking whisky in my underwear during the season’s first light snowfall. I had roared upriver in an aluminum skiff with Zeb Hogan, a curly-haired Wisconsin fish biologist, and Brant Allen, an experienced taimen researcher from UC Davis. Brant had asked us to help make a “visual survey,” which turned out to mean swimming down the Uur, three abreast, trying to drive the fish toward Zeb’s Nikonos camera. At a long, gentle curve in the river, we unloaded the boats and started warming ourselves pre-dunk with Johnnie Walker Black and a driftwood fire.

The view encompassed every combination of wild beauty, with steep, snow-dusted mountains in one place and bright sun falling on yellow larch in another. Some scholars believe that our love of spectacular landscapes may be less the product of sentiment than of natural selection. As early as 1.5 million years ago, they argue, our ancestors were genetically imprinted to favor views like this: a valley with hunting grounds; grass to attract animals; a river with clean water; trees for ambush and escape. According to this “woodland-mosaic hypothesis,” we are drawn to the patchwork of nature. Just as trout stalk the seam between two currents, we reach for the borders between states of being.

Hopping from foot to foot, we wrestled into drysuits, masks, and snorkels, adding neoprene hoods, booties, and gloves against the cold. We flailed into the Uur and were immediately swept downstream, bobbing like corks and just as helpless. Before I could even gesture at it, the first taimen was gone. But there was another, at once, a silvery juvenile in the lee of a rock. It dropped back warily, looking a bit surprised by my arrival. I lifted a hand to start herding and immediately flipped upside down. By the time I righted myself, I’d spotted another taimen and a pair of lenok.

All week I had angler’s blindness: Because I caught few fish, I believed there were few fish. But here it became obvious there was a taimen or a lenok for every 20 feet of good river. Brant and Zeb had flushed as many as I had. We got out, laughing for no reason. A few seconds on the bank, in the wind, was enough to send me jogging upstream toward the fire.

AS THE DALAI LAMA might say, torturing a fish ain’t kosher. That night, our fifth in camp, I had a nightmare in which my karmic payback was to be reborn as a worm. The next morning Jim looked over from his Mickey Mouse mattress on the far side of the ger and said he too was sleeping badly, dreaming a lot.

“War dreams?” I asked.

“No,” he replied, rolling over. “Those are different.”

There was no escaping the world, even here. Jim carried a tiny short-wave radio, but in these high valleys we could hear only Chinese and Russian voices. Fishing is thieving time from that outer world, a way of escaping from responsibilities, news cycles, and the tiny vibrations under the floorboards that signal the approach of some new existential tsunami. Fly-fishing may be an indefensible activity, but play, rest, beauty, and freedom are crucial to sanity and survival. Time, however, doesn’t pause just because we do. Charlie had a satellite phone in his tent, and I used it to call home. Normally I preferred my wilderness deep and disconnected, but my expectant wife had been feeling poorly before I left.

The signal bounced off a geosynchronous bird and jingled a receiver in Brooklyn. My wife picked up, in tears. Something was wrong. She was in terrible pain.

The signal coughed and sputtered, making gibberish of the simplest words. “Miscarriage,” she said. “The doctors think it might require surgery.” In less than a week, perhaps, depending.

For 13 minutes and 46 seconds my wife and I talked, and I hung up the phone to the sound of her crying.

The love of remote places, the unreasonable desire to know all of this world, leaves us hostage to fate. My father had been diagnosed with terminal cancer when I was living on another continent. Standing in an airport once, I learned from voice mail that my apartment and everything in it had been destroyed by fire. And now another lost pregnancy.

Surgery. In days. After I hung up, I said to myself what I had just said to her, in the 13th minute: I will be there.

I wanted to go home. Now. But wilderness is unmoved by our needs. That is the point in seeking it, and it is a sharp point. Now, in Mongolia, means three days from now. There was no way out until Monday, when the orange Mi-8 would pick us up shortly after dawn.

I counted the days on my fingers. Friday, Saturday, Sunday, Monday. A lifetime. If I could get out of Ulan Bator by Tuesday, I might reach South Korea Wednesday, Los Angeles the day after that. Then, just maybe, I could make it to New York in time.

IN ONE WEEK the trees had surrendered their colors, the nighttime temperatures had plummeted, and the rivers were shutting down. The taimen vanished from knowledge then. Local lore held that they migrated up the Eg to Lake Hovsgol, or downstream to Lake Baikal, but the scientists’ partial evidence indicated that they probably stayed right where they were.

I willed myself to believe that the earth would spin, the river would flow. The aircraft would come. And on Sunday, with one finger left on my calendar, I fished.

Charlie had seen, once, a big taimen resting in a deep bend of the river. We drifted quietly down into it and he pointed out where an old landslide had poured down a bank into the water. “That’s where you’re gonna catch him,” he said.

On the last day of the last week of the brief fishing season on the last river full of taimen, I made one last cast. I dragged an immense black popper across the current, and the hit was so big that I thought Jim had thrown a bowling ball into the water. I hooked, played, and then, after 20 seconds, lost the fish. The mouths of taimen are hard as metal plates, and they throw off a lot of hooks.

The foam fly bobbed to the surface as the blood ran out of my face. Charlie had said a hundred times that taimen will come back around and hit a fly again. Paralyzed, I let the fly ride there, every ounce of attention coiled into my hands, but nothing happened.

Yet luck is made. Second chances are made. I lifted the fly, arced a single false cast, and dropped it back over by the landslide. Nothing. In despair I pulled it in toward the boat, slowly, the way Charlie had taught me. This time the taimen hit with a whitewater splash full of teeth, dived back down with a flash of dark tail, and then the fly and the fish came tight on the line, thrashing.

By the time I wrestled it in, my arm was trembling with lactic exhaustion. Taimen are not spectacular fighters, but their size and weight make it a brutal contest. “Thirty-seven inches,” Charlie said, looking up from the net. Almost a meter long. This wasn’t Anna Nicole, but the fish was fat enough to melt over my fingers like Monterey Jack in a microwave. Holding the sleek gray beast out of the water, posing for photographs, I accumulated some seriously bad karma.

Before releasing it, we studied a deep, round scar in its back. The fish appeared to have survived a stabbing by poachers, who use long wooden tridents. I revived it until my fingers were numbed by the Uur, and the taimen abruptly kicked its way free.

Five minutes later we saw the fish one last time. It was finning slowly against the sandy bottom, down in the black heart of the river. Tired, but still alive. A survivor.

I TOOK JIM’S ADVICE and peed before getting into the helicopter, and the magic carpet had us in Ulan Bator by lunch. A veteran of many goodbyes, Jim simply handed me his old copies of Time and caught a flight to Beijing. Then Central Asia kicked in: A sudden windstorm shut down the airport, stranding me in the capital, amid broken sidewalks and construction cranes, for more than a day.

The phrase “My wife is in the hospital” can melt the coldest hearts, and once I reached South Korea I was allowed to simply walk onto the next direct flight to New York. We burned up and over the glacial reaches of Alaska, nicked the Arctic Circle at 33,000 feet, and finally, 14 hours later, dropped into New York, bathed in solar radiation and unwatchable movies the whole way.

From there, everything went terribly, shockingly right. I stumbled into the hospital just as my wife was signing the consent form for anesthesia. When I dropped all my fishing gear, a cloud of Mongolian dust rose into the sparkling room.

The surgery was far worse in anticipation than in the actual event. Twenty brief minutes and a clean bill of health, with walking papers that afternoon. That night we lay in bed, exhausted, infinitely relieved, listening to the elevated train rumble past our brick house and to the vain wailings of car alarms down by the Gowanus Canal.

So that is one last reason to go to Mongolia, to go such a terrible distance away. You have to learn that paradise is not a silver creature in a black stream lined with pine trees. I’d found my good place. Nothing could touch us here.