GLENN CLOSE AND I ARE HEAD OVER HEELS. Ass over teakettle we tumble, from our raft into the spin cycle of the Rio Futaleufú;. It is a perfect day: The sun is shining and the river is beautiful—a shimmering, effervescent foam that glints like a shower of sapphires as it closes over my head. Suddenly I’m hit with a preconscious instinct, my own reverse Elephant Man moment. I am not a man, I am an animal: Follow the bubbles to the surface!

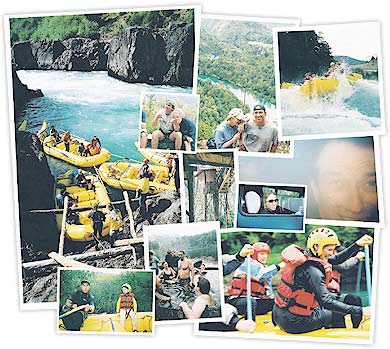

The froth is disorienting, churning in every direction, with no clear way up. But flotation being what it is, the combination of our life jackets and the powerful arms of Robert F. Kennedy Jr. (Bobby for short; president of the Waterkeeper Alliance, senior attorney for the Natural Resources Defense Council) does the trick. Glenn and I are hoisted, dripping, back into the boat, our ordeal all of five seconds from start to finish.

Cutting through the green, snowcapped Andes in southern Chile like a satin ribbon, the “Fu” is nirvana for paddlers. Along with mind-bending Class V rapids, the river has two unique features: On its 120-mile, 8,000-foot descent to the Pacific, the Fu’s meltwater stops in several lakes, which simultaneously warm it—at 61 degrees, it is considerably more temperate than most glacially fed rivers—and filter out almost all the silt. This accounts for the Fu’s supreme clarity. By the time the water reaches the riverbed, it’s an astounding teal-blue, more Caribbean than Patagonian.

This is our last day on—and briefly in—the river. Glenn, 56, grins widely as we resume our positions in the raft, her already enviable bone structure somehow enhanced by this brush with mortality. I wish I could say the same for myself. I’ve traveled halfway around the world to write about celebrities behaving badly on an expedition meant to bring attention to an endangered river. But most of them—Woody Harrelson, Julia Louis-Dreyfus, Richard Dean Anderson—didn’t show up. And the ones who did—Bobby, his wife, Mary, and their longtime pals Glenn and New York hotelier Andre Balazs—all brought their kids. So I’m heading back with new friends and a story of a dam development scheme that seems more sleeping giant than clear and present danger. But not before having the crap scared out of me.

TRAVEL WITH A KENNEDY and you occasionally feel like you’re on the road with a major brand: Mickey Mouse, say, or the Coca-Cola logo. There’s a surreal quality to meeting RFK Jr. for the first time, at JFK. Kennedy, 49, has assembled two dozen people for a trip that will be part adventure tourism, part consciousness raising: The Futaleufú; is facing a proposed dam project by multinational corporation Endesa, Chile’s largest electric company.

We are being led by Earth River Expeditions, which started running outfitted trips down the river in 1992. Based in upstate New York, the organization has been buying up property along the Fu to keep it out of Endesa’s hands. Earth River currently owns about 1,500 acres—land goes for about $3,000 per—upon which about ten homesteaders live. The agenda behind a trip like ours is that we will return home and, through word of mouth, send others down the Fu, enhancing its value as a well-traveled ecotourist destination and making it a viable economic alternative to a hydroelectric dam. Or there’s the best-case scenario, from Earth River’s standpoint: One of the wealthier rafters in our group will buy a piece of land and put conservation easements on it so that it can never be sold to a power company. (Endesa is a corporation, not the government; it would have to own any land it proposes to flood.)

Earth River’s cofounders are Eric Hertz, 48, an American with the youthful, blue-eyed friendliness of Greg Kinnear; and Robert Currie, 44, a Santiago native of Scottish and Chilean parentage, with the physique and demeanor of a benign Hercules. Hertz waits in a cataraft for ejectees at the bottom of each set of rapids, and Currie is our trip leader. We’ll be on the Fu for six days in three rafts, starting at Infierno Canyon—roughly 25 miles from the river’s headwaters at Lake Amutui Quimei, in Argentina’s Sierra Nevada—and descending 45 feet per mile for the next 25 miles down to the rapids of Terminador. Glenn and I are in the grown-ups’ boat, behind Bobby and Mary, who have been taking rafting trips together since 1977, before they were even sweethearts.

Currie mans the oars in the back and precedes each run with a few minutes of river reading. On our first day, as we near Alfombra Magica (“Magic Carpet”)—our first Class IV challenge—he points to the geography of chaos roiling below.

“We’ll ride down that ridge of water and then we’ll typewriter across and back up when we get to the second drop,” he says. “Then we’ll paddle over to the eddy, which will stop our drifting.”

“I knew an Eddie once who stopped my drifting for a while,” Glenn deadpans.

As we sit at the top of each rapids, I can always see exactly what Robert is talking about. Once we’re in it, though, it’s a barreling spume of foamy white and Scope green. Where are those watery landmarks he described? I have no idea. It doesn’t matter, really—he can see them, and that’s what counts. As his crew, we only have one job: to do what he tells us. More often than not, that means paddle like hell. And even though at times it seems impossible that our efforts could be doing much of anything—those moments when our paddles stew nothing but the air as the river drops out from under us—we are apparently Currie’s power source.

And his mouthpiece. Kennedy is somewhat deaf in his left ear, and the river is loud. It falls to me to scream out Currie’s instructions. “Back it up! Stop! OK, dig in, dig in, dig in!” Later, when I get back home, I’m sent a copy of the video of our trip. I am talking in every shot, as if spooling out a monologue of fear. But there’s no way to run the Fu without making a sound of one sort or another. Glenn laughs exuberantly, while I opt for yee-hawing in what I hope sounds like an approximation of “Isn’t this fun?”

It is fun, in large part because I’m not steering. Currie’s skill gives the danger a virtual quality; it’s more like watching an exciting but consequence-free film of a river than being on one. I start to feel downright cocky.

EARTH RIVER HAS THREE CAMPS on the Fu, where we will stay over the next six days. The first is Camp Mapu Leufu, a rolling meadow that ends abruptly at the edge of a cliff, its springy grass littered with ox pies. Our routine is less than strenuous: Each evening we peel off our wetsuits and head for the hot tub. There is one at every camp. What initially seemed like so much Marin County nonsense proves indispensable, our best chance to get warm after a day spent on a chilly river. We’re treated like true adventure pashas—beer, snacks, excellent meals. We can even schedule a massage in our tents. With about a dozen children, ranging from seven to 18, we spend hours telling stories around the fire every night.

“A man checks into the Plaza Hotel in New York,” Kennedy says one evening in his gravelly Jimmy Stewart-like sob. “He eats too much for dinner and goes to bed. He wakes up a few hours later to find himself marinating in diarrhea.” That line is a big crowd-pleaser. Kennedy goes on: Horrified, the man throws his sheets out the window. They land on a wino, who wrestles them off and confusedly tells a cop he thinks he “just beat the crap out of a ghost.”

There is grown-up talk as well. A good deal of it about politics and, not surprisingly—given that we are traveling with Kennedys and a bona fide movie star—some really choice gossip. I’m sworn to secrecy, but it doesn’t really make a difference: I don’t recognize most of the names. By the time I’m back in my tent, all I can remember are “World Bank” and “Vanity Fair airbrushed his Speedo bulge.” Our wetsuits are hung overnight near the fire. By morning, the neoprene isn’t exactly dry, but it’s taken on a comforting bacony quality. The white noise of the Futaleufú; is good for sleeping, though it also serves to wipe clean whatever confidence I gained the previous day. I wake newly terrified, as does Glenn, I’m pleased to find out. This is as it should be, according to Currie. Especially because today, our first full day of Class V rapids, we are running Infierno Canyon.

“The day you think about Infierno without your hands doing this”—Robert shakes his like Al Jolson singing “Mammy”—”is the day to quit rafting the Fu.” This is no place for false bravado, he tells us, and seeing the sheer rock walls of Infierno up close, it would be hard to muster any. Even the names of the rapids suggest meeting your maker: Purgatorio, Danza de los Angeles, Escala de Jacobo. Once in, the only way out of Infierno is by running it. We couldn’t portage here even if we wanted to. Yesterday I was aware of the river and others in the raft; today my peripheral vision narrows to nothing. It’s just me and the end of my paddle.

THE RAPIDS DON’T take very long—r at least they seem not to. Time accordions when you’re on the river. The water widens out and quiets. Vegetation creeps back onto the cliffs, which get lower, opening out to gently sloping forest and pastures in places. We throw a Nerf football from boat to boat. (Well, they do; over the years I’ve perfected my “Please don’t throw the ball to me” face.)

Kennedy fly-fishes off the side of the raft and catches a ten-inch rainbow. When he removes the hook, the trout slips out of his hands and into the limited freedom of our boat, where it spends the afternoon swimming back and forth in the bilge. Sadly for this fish, the Fu is not a catch-and-release river; by nightfall it’s headed down one of the most famous intestinal tracts in America.

It is one of only two fish I see the whole week. The other is an ancient bull of a salmon, easily 40 pounds, which swims unmolested through the frigid waters. I also see two birds, kingfishers both. And that’s it. Not one insect, rodent, or small reptile. The Fu’s food chain appears to be as exclusive as our group: crowded at the top. There are apparently two types of deer, one subspecies of puma that eats the deer, and an alien population of wild boar brought over from Africa by the Argentinians. The pigs, huge omnivores with no natural predators, are of such mythic proportions, Hertz tells me, they can upend a man on a horse.

Such a preternaturally shy ecosystem wouldn’t seem to encourage living off the land. This might account for the short history of the region, which was only settled in 1905, when the Chilean government offered its citizens land grants to stave off annexation by Argentina. Chilean settlers found no recent evidence of inhabitants, but indigenous people must have lived here at one time or another—utaleufú is, after all, a Mapuche Indian word meaning “great waters” or “grand river.” Until Chile blasted a road through the region from the coastal fishing village of Chaiten, in 1986, the only way in by car was via Argentina. Even today, a scant 800 people live along the Fu—00 of them in the hamlet of Futaleufú and the rest on small farms or backcountry homesteads. All of which makes it an easy target for a dam project.

The vibe on our trip is fairly urgent—ell, as urgent as you can get sitting in a hot tub, sipping Chilean cabernet—ueled as it is by the cautionary tale of the Bío-Bío. Home to Chile’s indigenous Pehuenche people, the Bío-Bío river valley was once the Chilean equivalent of the Grand Canyon and one of the world’s premier whitewater destinations. Endesa—ith the Chilean government’s blessing and a loan from the International Finance Corporation (IFC), a subsidiary of the World Bank—lanned a series of six dams on the river, starting with the Pangue, a 450-megawatt operation that would create a 1,250-acre reservoir.

In 1992, Kennedy, along with lawyers from the NRDC, pointed out to the IFC the major flaws in Endesa’s plans, including the fact that the dam was to be built in the middle of an earthquake zone at the base of two volcanoes. The World Bank, already under scrutiny for funding some environmentally questionable projects, launched its own internal investigation. In the end, an international coalition that included the NRDC, the Chilean Commission on Human Rights, and Grupo de Accion por el Bío-Bío, a grassroots organization, managed to keep Endesa from building all six dams. However, the Pangue devastated much of the Bío-Bío’s whitewater.

Endesa wants to build two dams on the Futaleufú that would bracket the river like concrete parentheses. The 800-megawatt La Cuesta facility would sprout up about nine miles from the village of Puerto Ramirez, our take-out. The 400-megawatt Los Coigü dam would sit just below Infierno Canyon, gateway to the river’s prime whitewater. Above that dam, local farms would be flooded under 75 feet of water; below the dam, there’s a distinct possibility that the rapids could slow to a trickle. As for the power generated, a good portion of it would probably be sold to Argentina.

In addition to trying to keep property out of Endesa’s hands, Earth River is waging its battle in the court of public opinion. One of the perks of being a river pioneer is getting to name rapids, and in 1991, when Hertz and Currie made their first descent of the Fu, they were vigilant about giving them Spanish or Mapuche names. (Endesa had tried to characterize the campaign to save the Bío-Bío as an affluent gringo insurgency, pointing out that some rapids, like Climax, were identified by English vulgarities.) The harsh reality of eminent domain, however, is that if the Chilean government really wants to hand over the Fu to Endesa, no amount of privately held riverfront property will make a difference.

Which makes it hard not to feel like a play-acting gringo insurgent. I had envisioned a trip where the whitewater thrills would be mixed with white knuckles of a different sort, as we bravely faced down bulldozers and sand hogs, blocking their way with our bodies, making us truly worthy of those long hot-tub soaks at the end of the day. But when I ask Hertz how dire the threat is, he puts it at about ten years off.

“Endesa hasn’t been buying up the land, and they need every piece they’re going to flood,” he tells me. “I think the fairest thing to say about the dam is that it’s in the future. People shouldn’t think they have to race down here, because it’s not true. But the more people who see the river…”

He’s not being a Pollyanna. When I call Endesa, in Santiago, I hear much the same thing. One energy planner guesses that getting these dams built by 2020 would be “optimistic.” “These projects are not confirmed,” adds Endesa communications manager Rodolfo Nieto. “They are only a far, far, far possibility.”

Perhaps, but it can’t hurt to get a 17-year head start when trying to halt a multinational hydroelectric concern. Kennedy certainly seems to think so.

“I’ve just seen this so often that it’s not even a question to me,” he says. “The locals get trampled. Dam projects like this consume their economies, devour them, and essentially liquidate them for cash. I’m worried about losing the Futaleufú.”

I’M WORRIED, TOO, but mainly because it’s our last day on the river and we’re about to run Terminador, the most challenging rapids of the trip. We take on some preliminary Class IVs in the morning—Caos and La Isla, which is where Glenn and I take our spill. It shakes me up more than I care to admit.

“How are you feeling?” Currie asks as we wait in an eddy above the rapids. Scared, we tell him. He demonstrates a Chilean gesture for our fear, bringing his fingertips together like a blossom closing up for the night.

“Get it?” he asks.

Kennedy guesses that it’s our balls shrinking down to the size of cocktail peanuts. No, Currie corrects us, it’s a sphincter tightening.

“That’s not a sphincter!” I shout. “A sphincter goes like this.” I make a fist and close it up tight like Señ;or Wences from The Ed Sullivan Show. S’alright?

Not really. I can’t remember much about Terminador, except that the force of the water seemed much more aggressive than on the other rapids, as if it were holding a grudge—the difference between a schoolyard bully and a Teamster with a baseball bat. It moved with such speed and magnitude that we had to stay close to the bank, which meant negotiating a steep drop backward at one point. Thankfully, Kennedy waits until we’re through it to tell me that it’s the most dangerous commercially run rapids in the world.

No matter, we’re alive and on to Himalayas, which is, by comparison, quite safe but possibly more thrilling. The waves are solid slopes of water easily 20 feet high, judging by our 18-foot-long raft. We ride up and down three or four of the aqueous mountains and we’re out, drifting safely in the eddy—wet, exhilarated, and done. Our last night in camp is a traditional Chilean asado. Two lambs—recently gamboling on the meadow near our tents, no doubt—have been slaughtered, butterflied on racks, and roasted on an open fire. The portions are medieval: great haunches and joints. We sit around a large square table, tearing into our food like Neanderthals.

After dinner, standing in the meadow at Mapu Leufu, there are more stars than I’ve ever seen, and that includes the pot-enhanced heavens of the “Laser Floyd” show at the planetarium. “Wow, wow, wow,” I whisper. I can’t even hear myself over the rush of the river.

HERE’S WHAT I LOST ON THE FU: two pairs of sunglasses, a water bottle, a carabiner, and my useless quick-dry towel, which swings, probably still damp, on a line somewhere.

Here’s what I didn’t lose: my life.

Here’s what I got: a new hat. When we pull the rafts out at Puerto Ramirez, Kennedy presents me with a baseball cap bearing the crest of the Swiss flag with an image of a tiny airplane clearing an alp. An adventurer’s cap.

“You don’t like my Krispy Kreme hat?”

“You’re so much more than a doughnut,” he replies.

He’s wrong, of course. I’m so much less.