TWO ENGINES START UP with a guttural purr, the sound muffled by knee-deep California powder. A hundred yards apart, separated by a mogul field, a pair of men mount their fidgety Polaris snowmobiles. Behind them, the Minaret peaks claw at a hyper-blue sky.

warren miller

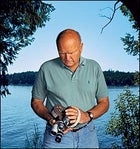

“It’s Been Fun So Far”: Warren Miller at his home on Orcas Island, Washington

“It’s Been Fun So Far”: Warren Miller at his home on Orcas Island, Washingtonwarren miller

The Original Ski Bum: Miller in 1947, checking his wax in Sun Valley, Idaho

The Original Ski Bum: Miller in 1947, checking his wax in Sun Valley, Idaho

“Warren and Dave. Take one!”

The production assistant snaps a slate and ducks behind the cameraman. As an Arriflex 16-millimeter starts rolling, the riders lurch forward, gaining speed as they pitch off huge snow mounds. Suddenly their faces are visible, their ruddy cheeks stretched flat in demonic grins. The character flying in from stage right is Dave McCoy, legendary founder and owner of Mammoth Mountain ski resort and a former trainer of Olympic skiers. Growling in from left is Warren Miller, the puckish godfather of extreme-ski cinema and our nation’s original ski bum.

Miller turns 80 on October 15. McCoy is 88. But no one here believes it. Ski buddies since the 1940s, they’re being filmed in Mammoth’s backcountry for the 2004 Warren Miller film Impact, which opens October 21 in Portland, Oregon, before rolling out to 180 U.S. cities and seven other countries. Shots of Miller romping with his merry-prankster pals are a cherished part of these movies. It’s one slightly indulgent ingredient in a successful formula that, year after year, pulls in more than half a million raucous fans, who pay up to $18.50 a ticket. Impact will be Miller’s 55th feature film—and possibly his last.

Miller is an imposing six foot one, with a giant bald head and a strapping chest stuffed inside his signature Dale of Norway sweater. He’s blocking out this scene himself, using pine boughs to indicate where he and McCoy will make their final vaults so that, from the camera’s perspective, their snowmobiles will appear to intersect in midair, like crossed swords. As McCoy and Miller bound over the last few moguls in near-flawless rhythm, there’s a goofy synchronicity to the moment, as if Esther Williams were choreographing a scene from Mad Max.

Finally, the men launch off their respective jumps and sail past each other, a feat that should look great in slo-mo. Unfortunately, the cameraman didn’t get the shot he wanted.

“Gotta do it over, Dave!” Miller yells, feigning dismay.

“OK!” shouts McCoy.

With that, they spin their machines around, rev ’em up, and do it all again—two raging geriatrics, trying to form a perfect X.

WITH UPWARDS 570 FILMS bearing his name for the big screen, television, private companies, and ski resorts, Warren Miller is the most prolific sports cinematographer of all time, and an instigator of our culture’s endless fascination with extreme. He’s championed the stoked life in nine books, in countless newspaper and magazine columns, on the speaking circuit, and from his favorite pulpit—the chairlift. If you’re ever lucky enough to spend ten minutes riding with him up a high-speed quad, you’ll hop off and head directly for the steepest chute or most bodacious jump you can find.

“Go get your freak on!” Miller will likely say. “Whatever it is you want to do, you have to do it now!”

Miller has lived by his own mantra—he’s tried just about every thrill sport there is. In his (slightly) younger days, he won amateur ski races all over the American West, became a crack sailor, and surfed many a righteous California break on a 100-pound redwood board. In 1968, he out-skied an erupting volcano while filming Jean-Claude Killy in New Zealand. Just a few years ago, he windsurfed from Maui to Molokai, having taken up that sport at the ripe young age of 60.

“I’ve been a little out of the box my whole life,” Miller quips.

He was born in 1924 on the kitchen table in the middle of a party at his parents’ house in Hollywood, California. His father, an architect, lost everything during the Depression and slowly drank himself to death. Miller’s mother sewed quilts for the Work Projects Administration. As a child, Miller was hungry for part of every day, and he slept in a closet until he was 13.

In third grade, he sold stink bombs to his classmates so that he could buy his first still camera, a Bakelite Univex, for 39 cents. He took it along on Boy Scout expeditions to Mount San Jacinto, where he learned to turn $2 army surplus skis. After graduating from high school in 1942, Miller entered the Naval Officers Training Program at the University of Southern California, where he studied astrophysics, played basketball, and drew cartoons. In 1945, Ensign Miller served in the Pacific on a subchaser that sank in 60-foot waves near Guadalcanal. After his 1946 discharge, Miller spent his bonus on an eight-millimeter movie camera. He launched his film career that winter from the ski-resort parking lot at Sun Valley, Idaho, where he and his surfing-and-skiing buddy Ward Baker lived out of a four-by-eight-foot camping trailer.

Miller and Baker made ski-bum history that season—managing to eat, sleep, and ski on a total of $18 apiece. By day they poached crackers and ketchup from the cafeteria to make a lame imitation of tomato soup; by night they scarfed jackrabbits they’d shot with a rifle. They became ski instructors, and to earn a few extra bucks, Miller took photos and drew cartoons of wealthy skiers he met on the slopes. “If it was a picture of the guy with his wife and family, I’d sell it for a dollar,” Miller commonly jokes. “If I had a shot of a fella with his mistress, it was $10, negatives included.”

Through two ski seasons, Miller and Baker photographed each other and the pantheon of celebrities drawn to Sun Valley—people like Groucho Marx, Ernest Hemingway, the Shah of Iran, and Gary Cooper. In 1949, free talent was indispensable in producing Miller’s first ski film, Deep and Light, shot in Squaw Valley, California, on a $427 budget, using a 16-millimeter camera on loan from two Bell & Howell executives Miller had instructed.

Extreme skiing was born on the reel in 1954, when Miller filmed Olympian Stein Eriksen doing a front flip. Audiences were stunned, and sponsors like Head Skis, Ford Motor Company, and Old Crow Whiskey signed on, enabling Miller to shoot in exotic locations all over the world.

Three decades later, in 1983, a young skier named Scot Schmidt changed everything when he hucked off a 75-foot cliff into neck-high powder at Squaw Valley. Ever since, Miller’s movies have steadily ratcheted up the adrenalized snowmanship, inspiring generations of skiers and sparking the rapid growth of the ski industry. Today, in the snow-sports category alone, dozens of companies are making movies, and films like Touching the Void and Riding Giants wouldn’t be playing in your neighborhood theater if not for Miller’s persistent trailblazing.

“Warren Miller is the man who made the snowball that created the whole industry,” says Dirk Collins, 34, cofounder of Wyoming-based Teton Gravity Research, a production company known for films like High Life and The Prophecy. Collins sees a direct lineage from Warren Miller Entertainment to TGR and the flock of young companies that followed Miller’s lead.

Like Miller, he says, “we’re all just living out our dreams—and figuring out how to get paid for it.”

ALTHOUGH MILLER HAS SKIED the world, Mammoth remains one of his favorite places. “It’s 72 degrees and there’s still 17 feet of snow—let’s go skiing!” he pleads, looking covetously up at his mountain arcadia. It’s a sunny afternoon the last week of March, and we’re trolling the slopes for more scenes.

Most of the aerial action at Mammoth takes place at Unbound, an über–terrain park with 30 acres of rails, jumps, and the headline feature, the superpipe, where everyone is either pointing a video camera or vamping for one. Miller and McCoy are here to interact on film with some of the crazier denizens of the park.

Traffic is dense in the stunt ditch. There’s a constant swirl of kids throwing corked 360’s and dinner-roll sevens. Emily Thomas, 26, an Australian snowboarder, pops off the lip of the quarterpipe, rotates, and drops back down the wall. Her husband is filming her for an Australian TV show. As McCoy whistles appreciatively, Thomas carves a sweeping arc and pulls up beside me.

“Is that Warren Miller?” she asks incredulously. “He’s the guru of ski films! I work eight months a year in Sydney so I can travel to the places in his films. My parents say, ‘Get a real job.’ And I’m like, ‘People make a living out of this. Look at Warren Miller!’ “

Miller loves being the jolly ski Svengali. “I feel like I’ve been selling an illegal substance,” he says. “People tell me how I’ve messed up their lives, because their kids are jumping higher, farther, faster. But if you don’t scare yourself at least a few times every time you ski, you’re doing something wrong.”

Suddenly, a pair of young snowboarders on the lift recognize him. “Warren Miller rocks!” they yell in unison. Miller raises his hand in laconic acknowledgment, then turns back to McCoy, a smile crinkling his pale blue eyes. Matty Smith, a member of the film crew, interrupts the moment with a little razzing.

“What’s that, Warren?” he asks, pointing at a lift ticket clipped to Miller’s pants.

“They wouldn’t let me on the lift, ’cause I didn’t have a ticket!” Miller says in mock outrage. “I said I’d left it on my other pants. That worked for about three runs, then I had to go buy one.”

“I want that ticket,” Smith says, turning to me. “That may be the only one Warren’s ever paid for.”

Despite being a millionaire, Miller is a strict practitioner of the ski-bum ethos, which dictates that all good truants must at least try to scam a lift ticket. “Wherever you go skiing,” he’s fond of saying, “spare no expense to make your trip as cheap as possible.”

As we’re about to get on the lift, a skier named Dennis Agee slips into the instructors-only chute and sits beside me. A former racer and U.S. Ski Team coach who starred in Warren Miller films in the 1960s, Agee knows a bit about Miller’s legendary frugality.

“Warren paid really well in those days,” he says facetiously. “You worked your tail off for three days—hiked cornices over and over so the cameraman could get his shot, skied terrain you had no business going down when you were that tired. And at the end, you got a Warren Miller pin!”

Agee laughs. “But it was an honor just to be asked,” he says. “That pin was the most prestigious thing you could wear. It was like an Oscar or an Olympic medal. You were a member of the most exclusive ski club in the world.”

MILLER LIKES TO BOAST that he’s pulled off “a lifetime of never having to work for a living” and has charmed people into coming along for the ride. But while his life has been long on adventure, it’s been short on family stability. He lost his first wife, Jean, to cancer when their son, Scott, was only 18 months old. Miller went on to have two more children—a daughter, Chris, and a son, Kurt—with his second wife, Dottie. But he was gone most of the time, filming or touring, and his second marriage crumbled, as did the next. His children have each found their way into the film business: Scott, 52, is a documentary filmmaker in Malibu, California; Chris, 47, is a photojournalist in Los Angeles; and Boulder, Colorado–based Kurt, 45, runs Synergy Group, which acquires and co-produces sports films for Regal Entertainment.

In the late eighties, having recently married his fourth wife, Laurie, a ski retailer, Miller was ready to step back from the frenetic demands of running a film company. By that time, Kurt, a world-class sailor who’d been making sailing movies that mimicked Warren’s formula, had carved out a niche within Warren Miller Entertainment. Kurt saw an opportunity to expand the brand by filming other sports his dad had taught him to love—surfing, skateboarding, BMX biking, and every possible mode of snow sliding—and marketing those films with gusto. In 1989, Warren sold his company—and his name—to Kurt and his partner, Peter Speek, for roughly $1.5 million. Although Warren continued to write and narrate the films, he was no longer calling the shots in the editing room or with corporate sponsors.

Warren and Kurt’s relationship was often stormy. According to a colleague who worked with both men, they clashed over almost everything. Warren accused Kurt of corrupting his magic formula with conspicuous product placement and long, uninterrupted music tracks by Dave Matthews and Counting Crows that drowned out Warren’s folksy narration. “It was not easy to work for my son,” Warren says. “I don’t know many fathers who could.”

Kurt had his own complaints—one being that the Warren Miller vibe was getting stale. Edgier ski-movie outfits like Greg Stump Films and, later, Matchstick Productions and TGR were luring 18- to 25-year-old audiences by rejecting Warren’s humor-travelogue schtick in favor of rowdier action, pumping soundtracks, and more focus on the Dionysian energy of the athletes.

“My dad should be telling himself, ‘I created the greatest thing in the world,’ ” Kurt says. ” ‘Yes, it’s being changed, but it’s my vision being sustained in a new way.’ I wish he could just enjoy it.”

Kurt expanded the company by kick-starting dozens of “downstream business acquisitions” in publishing, advertising, and corporate sponsorship. He produced shows in places like Antarctica for the Outdoor Life Network, ESPN, and the Discovery Channel.

Four years ago, in June 2000, Kurt sold Warren Miller Entertainment to Time Warner for somewhere in the neighborhood of $7.5 million. The company Miller had spent a lifetime building—along with his archives, his voice, and his name—all passed into the hands of the largest media conglomerate in the world. Warren and Kurt have barely spoken since. They will see each other this fall at a surprise party for Warren’s 80th birthday. Kurt, for one, genuinely hopes their relationship will mend and that Miller’s movies will carry on in the spirit Warren made them.

“People have grown up on my father’s films for 54 years,” says Kurt. “Whether I’m involved or my father is, I hope it continues.”

MILLER’S QUEST TO LIVE THE DREAM has paid off in other ways. It’s an overcast, snowy day in March, and we’re flying into Bozeman, Montana, at 600 miles per hour on a Gulfstream 100 on loan from a friend of Miller’s. Our destination is the most exclusive ski resort in the world—the Yellowstone Club, in nearby Big Sky. Since its creation in 2000, Miller has been the director of skiing at this members-only resort tucked away in the Madison Range.

Hank Kashiwa, the Yellowstone Club’s vice president of marketing, greets us at the Buffalo Bar and Grill, where fur-collared women and men in starched jeans are wandering in for an early-afternoon cocktail. Kashiwa is a former Olympic skier and TV commentator. As I sit talking to him, I’m watching empty chair after empty chair circling the main lift just outside the window.

“We have nine lifts, with a capacity of 5,500 people per hour,” Kashiwa says, “but we usually have about 35 people skiing a day.”

Kashiwa waits for my face to register seismic disbelief, then gives me the membership lowdown. Fee to join? $250,000. Yearly dues? $16,000. Building requirements? One lot will set you back $1 million to $8 million, a spec house $3 million to $12 million. For that, you get a cap that reads private powder, your choice of 50 trails, service from a staff of 278, and lift rides with Warren Miller.

Miller seems completely at home at this gated mountain, rubbing parkas with people like Jack Kemp, Dan Quayle, and 148 of their wealthiest friends. “The second time I skied here,” he says, “there were only six other people: Jack Kemp, Benjamin Netanyahu, the club’s owner, and three bodyguards.”

He scoots me out the door and onto the vacant high-speed quad. From inside the windless pod, he points out his nearly finished 6,000-square-foot house, which will have an unimpeded view of the immense stone-and-timber Warren Miller Lodge being built. Just over the ridge is a run called Miller Point. Miller’s old films run on TVs in every lounge, lobby, game room, and bar. His name is everywhere—it’s the Temple of Warren Miller.

“Isn’t this just incredible?” he asks. “There’s not a single track on this hill. Go on—make your turns really wide!”

We take a few runs down the lonely slopes, and I needle Miller about what a grueling job he’s taken on. Director of skiing? As far as I can tell, the job requires only his occasional presence. I ask a lift operator—who’s deep into a nice, fat novel—the longest he’s waited for a skier to show up and ride his lift.

“Three hours,” he says.

There’s an awkward friction between Miller, rollicking ski bum of the people, and the exclusivity of a place like the Yellowstone Club. But given the abject poverty Miller grew up in, it’s hard to fault him for his extravagances.

BESIDES, HE’S GIVEN plenty back. Miller has devoted his formidable drive to making the world better by sharing his passion: the pursuit of freedom through sports. His do-it-now instincts never flag, even when he’s at home on Orcas Island, north of Seattle in the San Juans.

The spartan public ferry taking me there is less glamorous than the private jet we flew to Montana, but it’s a gorgeous July day, and Orcas is bucolic and unassuming—an undeveloped Pacific Nantucket. The road to Miller’s place meanders past fruit orchards and grazing horses.

“Living here has added 15 years to my life,” Miller says, greeting me at his handsome Arts and Crafts house, with its Asian rooflines and cedar shingles. The backyard slopes down to a cold blue finger of Puget Sound, where Miller keeps his favorite toys—a skipjack, two kayaks, and a 47-foot yacht. “Sometimes I think it’s pretentious,” Miller confesses, “but I’ve grown to love it. I often think, What have I done to deserve all this?”

Miller’s next book is a humorous look at how not to age. He would love to become our national spokesman for habitual youth, and he’s hoping this book will start a new tack in his career, particularly since his future in film looks uncertain. Miller’s current contract to write and narrate movies expires in December. He feels he’s been steadily marginalized since he sold the company, and under Time Warner’s management the process is only accelerating. “What bothers me,” he says, “is that they’re showing too much extreme stuff and not enough giggling. Without my voice, it’s just guys turning their skis right and left.”

When I ask Perkins Miller (no relation), vice president of Mountain Sports Media—the Time Warner subsidiary that now runs Warren Miller Entertainment—whether Impact will be the last film Miller will narrate, he answers, “That hasn’t been determined. We’re looking forward to having a conversation with him this fall…” Then his voice trails off. “Unless he’s told you this is his last film.”

Whatever his next role, Warren Miller will always have his finger on the young pulse of action sports. He feels, as he likes to put it, “like a 14-year-old trapped in a senior citizen’s body.” He drives me to the new state-of-the-art $225,000 skate park he started building on Orcas after raising just $65,000. “I said, ‘If we dig the hole, the money will come,’ ” Miller says in mock-Confucian tones. “And it did.”

The park is thrumming with kids going huge and pumping up and down smooth concrete walls. Miller waves to a 12-year-old on the far side.

“Hey, Warren!” the kid shouts.

“Where’s the camera, Tyler?” Miller asks.

“Forgot to bring it today,” the boy says sheepishly. “But I’ve been filming every day this summer.”

Miller was watching Tyler skate one day and thought he had potential. He met Tyler’s mom, a housekeeper on the island, and learned she was raising him on her own. So he gave Tyler a video camera and said, “See what you can do with this.” It was a pay-it-forward gesture from a man whose early circumstances mirrored Tyler’s and whose own life was changed every time someone believed in him. “Put the right tools in kids’ hands, and good things happen,” Miller says.

He drives home the long way, showing me a few other pet projects: a BMX park and a YMCA summer camp, which he recently outfitted with a fleet of secondhand sailboats. Later, we’re getting ready to take Miller’s yacht to his favorite seafood joint, over on San Juan Island. As we grab our coats, we stand in his den, gazing at a ten-foot wall covered with photographs of family and friends, politicians and ski heroes. There’s Warren filming from atop a greasy gondola a thousand feet above Chamonix, and cooking rabbit stew with Ward Baker. I get the feeling there are many more pictures to come.

“It’s been fun so far!” he says, jingling the keys to his yacht. “Let’s get going!”