Murder on the Appalachian Trail

In 1990, a grisly double homicide on America’s most famous hiking route shocked the nation and forever changed our ideas about crime, violence, and safety in the outdoors

New perk: Easily find new routes and hidden gems, upcoming running events, and more near you. Your weekly Local Running Newsletter has everything you need to lace up! .

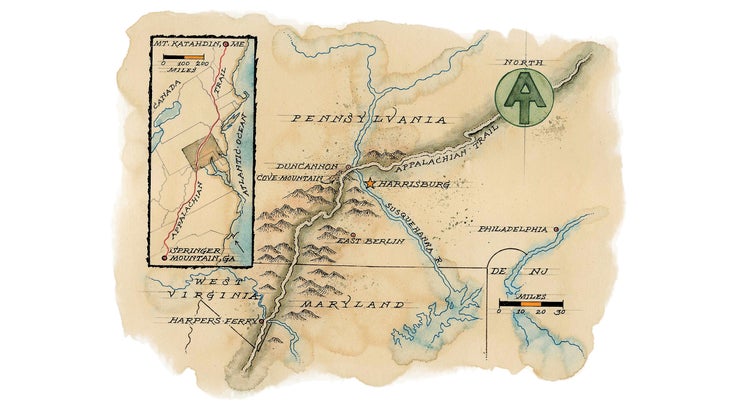

It is a quiet, restorative place, this clearing high on a Pennsylvania ridge. Ferns and wildflowers carpet its floor. Sassafras and tulip trees, tall oak and hickory stand tight at its sides, their leaves hissing in breezes that sweep from the valley below. Cloistered from civilization by a steep 900-foot climb over loose and jutting rock, the glade goes unseen by most everyone but a straggle of hikers on the Appalachian Trail, the 2,180-mile footpath carved into the roofs of 14 eastern states.

Those travelers have rested here for more than half a century. At the clearing’s edge stands an open-faced shelter of heavy timber, one of 260 huts built roughly a day’s walk apart on the AT’s wriggling, roller-coaster course from Maine to Georgia. It’s tall and airy and skylit, with a deep porch, two tiers of wooden bunks, and a picnic table.

A few feet away stood the ancient log lean-to it replaced. When I visited this past spring, saplings and tangled brier so colonized the old shelter’s footprint that I might have missed it, had I not slept there myself. Twenty-five summers ago, I pulled into what was called the Thelma Marks shelter, near the halfway point of a southbound through-hike. I met a stranger in the old lean-to, talked with him under its low roof as we fired up our stoves and cooked dinner.

Eight nights later, a southbound couple I’d befriended early in my hike followed me into Thelma Marks. They met a stranger there, too.

What he did to them left wounds that didn’t close as neatly as that fading rectangle in the forest floor. It prompted outdoorsmen and trail officials to rethink conventional wisdom long held dear: that safety lies in numbers, that the wilds offer escape from senseless violence, and that when trouble does visit, it’s always near some nexus with civilization—a road, a park, the fringe of a town.

And it reverberates still, all these years later, because what befell Geoff Hood and Molly LaRue at the Thelma Marks shelter is a cautionary tale without lesson.

Then as now, this clearing was a lovely place.

And near as anyone can tell, they did everything right.

It’s no surprise, what with the millions who use the path each year, that the AT had seen violence before the early morning of September 13, 1990. Five of its hikers had been killed in four attacks, the earliest in May 1974, the most recent in May 1988.

Those crimes shared traits with what transpired at Thelma Marks. Two of the four attacks were aimed at couples. Three came at trailside shelters. All were ghastly.

Still, none drew the attention, or generated the angst, of the incident here. Perhaps it was because Thelma Marks fell within range of news media in New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Washington, D.C., and because it involved not only a crime but a mountain manhunt that lasted a week. Perhaps the shelter’s remoteness—far greater than that of past trouble—played into our big-city uneasiness about what lurks in the woods at night.

The police thought Paul David Crews might have killed before. And now, late on the afternoon of September 11, 1990, he found his way to the Appalachian Trail.

Maybe it was the sheer savagery of the act. Or the questions that lingered when the man responsible would not say why he shot Geoff three times or why he tied Molly’s hands behind her back and looped the rope around her neck. Why he raped her. Why he stabbed her eight times in the neck, throat, and back.

“It probably took me a good 15 years to just process,” says Karen Lutz, then and now the top staffer in the mid-Atlantic region for the (ATC).

“I was up at the shelter. It was very real. It was very fresh. It was god-awful.”

Or maybe what set this sad affair apart were the victims, who combined competence, wholesomeness, and smarts.

“This might have to do with my age, but I find I get more emotional about it now,” says former Perry County, Pennsylvania, prosecutor R. Scott Cramer, who tried the case in 1991. “I get choked up thinking about Molly and Geoff.

“These were good kids. They were going to make a difference. All the indicators suggested that. And to have their lives snuffed out at that age—it’s a tragedy beyond words.”

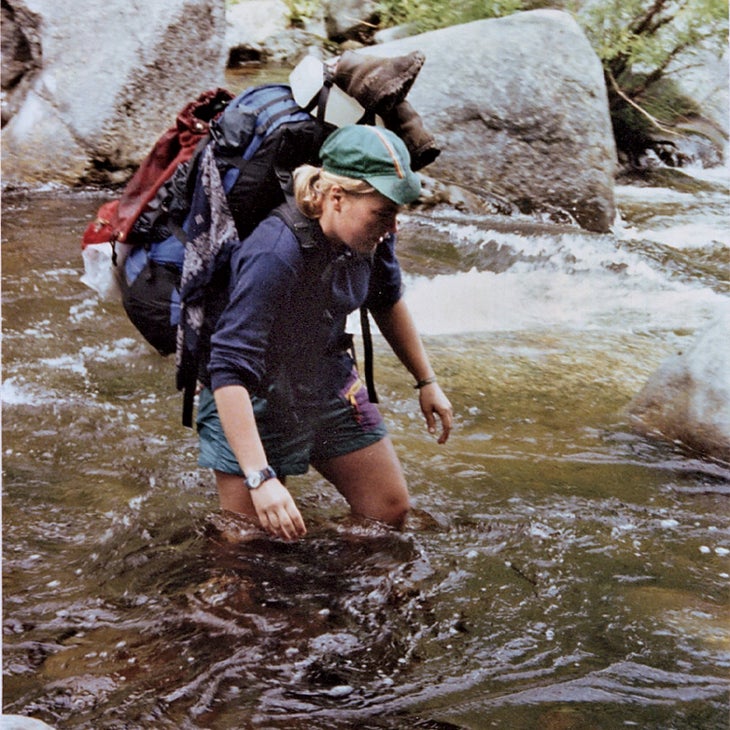

They’d met in Salina, Kansas, where both worked for a church-sponsored outfit that took at-risk youngsters into the backcountry to salve their troubles with adventure. At 26, Geoff was a friendly, contemplative Tennessean, even tempered and patient. Molly, a year younger, was a sunny, energetic artist who in high school had won a national contest to design a 1984 U.S. postage stamp.

They shared a love for kids and the outdoors. Geoff had rock-climbed in Colorado and taught climbing at New Mexico’s Philmont Scout Ranch. Molly had tackled two Outward Bound courses and spent a year providing wilderness therapy to kids in the Arizona desert.

They ventured onto the AT, as many do, at an unsettled juncture in their lives: they’d learned that, come May, they’d be laid off, and a six-month hike seemed a good way to decide what to do next. “We got a phone call from her one day,” Molly’s father, Jim LaRue, recalls. “She said, ‘You know I’ve always wanted to do the Appalachian Trail, and I have a friend here who wants to do it, too. Do you want to know something about the friend?’

“I said, ‘Yes, I would.’

“She said, ‘Well, he’s a male.’

“I said, ‘Are you announcing a relationship?’

“And she said, ‘Yes, I am.’ ”

By then she and Geoff were close to inseparable. “I love you forever, I like you for always,” he wrote in April, when he was off in the backcountry. “As long as I’m living my ALL you will be.” She cashed in her savings to finance their trip, which they’d start in Maine, as only one in ten through-hikers do.

And so, on June 4, 1990, having climbed the day before to the AT’s northern terminus on the peak of mile-high Mount Katahdin, they set off on their long walk—and found it surprisingly arduous. “We reminded one another before we started this ordeal that there would be tough days: Days we would ask ourselves, ‘Why are we doing this?’ ” Molly admitted early on, in a journal they shared. “Well, we had one of those days.” Geoff’s next entry whimpered: “Our bodies have had almost as much as they can take.”

But they also wrote in the logbooks left in shelters, which, in the days before cell phones, were the most reliable means for through-hikers to connect. Reading those entries made it obvious to all in their wake that they were enjoying themselves immensely.

Which is how I first made their acquaintance, in a poem Molly left in a Maine lean-to and signed with her trail name, Nalgene.

Last evening I whispered “I think there’re less bugs.”

This morning, BRING ON THE SLUGS.

Through the roof of our tent I see their familiar sludge

The stuff that resembles butterscotch fudge.

Squish between my toes in my sandal

Yuck! This is something I just can’t handle.

I read this a few days south of Katahdin, which I’d climbed 12 days behind them. I was stinking, blistered, and covered in mosquito bites. My pack weighed nearly half as much as I did, and every pound hurt. Black flies kamikazed into my eyes and mouth. I missed my girlfriend.

My first reaction was: How can this Nalgene person be so obnoxiously happy?

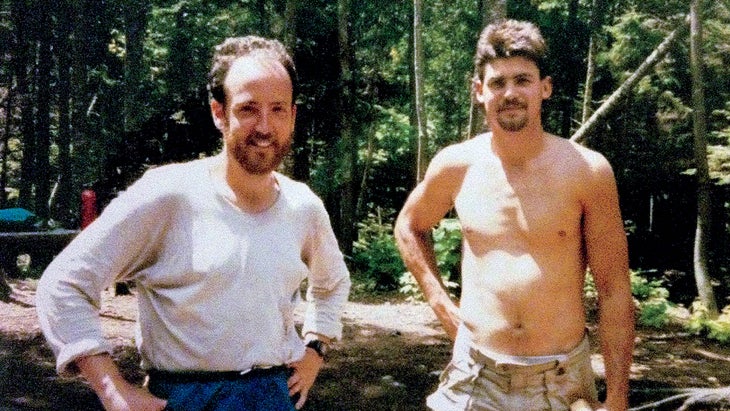

Eleven days into my hike, I stumbled out of the woods and into Monson, Maine, where I met Greg Hammer, an Army vet in his late twenties whose Virginia home was just a short distance from mine. Greg, trail name Animal, was easygoing and smart, and together we pushed into the windswept mountains of western Maine.

Along the way, the hikers ahead of us came into focus, none more so than Nalgene and her partner, who called himself Clevis. They left upbeat log entries at every shelter. They thanked the volunteers who maintained the trail. They gave shout-outs to other hikers, including one named Skip “Muskratt” Richards, whom they’d met in Monson. They were self-deprecating, funny, kind.

And they were slow. By the time I left Monson, I’d gained three days on them, and I was no speedster. At the New Hampshire line I’d picked up a week. As Molly predicted in one log entry: “If you’re behind us you will pass us.”

Their glacial pace was no accident. They were stopping to take pictures, to study plants, turtles, and salamanders, to bake bread. Animal and I resolved to catch them. We sped over the high, wild Presidential Range and down the 2,000-foot Webster Cliffs, setting up camp at the bottom two nights behind Geoff and Molly. Shortly after midnight, as I snored in my tent and Greg slept in his bivy sack, we were startled awake by a concussive thud: a rotted tree had toppled into the four-foot space between us, coming within inches of my head.

We eyed the near miss by flashlight, awed by the almost surgical precision with which fate had spared us—and unnerved that life or death could turn on such blind, stupid luck.

Our rendezvous came on Friday, July 20, at the Jeffers Brook shelter near Glencliff, New Hampshire, after we’d crossed an above-tree-line peak in a crashing thunderstorm. As I exchanged handshakes with Clevis and Nalgene, I told them that I felt like we’d already met. First impressions: Molly—blond and dimpled, quick to smile, solidly built but obviously fit. Spirited. Funny. A blue-haired troll doll dangled from her backpack. Geoff—bearded, beetle browed, and thin, with a smoky, high-pitched Tennessee drawl. I noticed that he carried one of the best packs around at the time, a mammoth green Gregory, and that both of them handled their gear with an expert nonchalance.

Our conversation was halted by the approach of a short, bearded man in a baggy black suit and large-brimmed hat, staggering under a pack that towered high over his head. Without a hello, he demanded that he be given the shelter’s east wall, where Greg had already set up. He huffed, impatient, when Greg didn’t jump to clear the space.

Irritated, Greg told the newcomer, whose name was Rubin, that he’d have to make do with the shelter’s middle. He unpacked, muttering, as our conversation resumed. Molly, Geoff, and I talked about Salina, where I’d interviewed for a job once. Greg chatted with two section hikers, Elizabeth and Chris, who’d been traveling with them for days.

Rubin interrupted. Why had I chosen my model of backpack, he wanted to know. He had heard it was bad. It’s worked just fine, I told him. Oh, you think it’s fine? Yes, I said, I think it’s fine. Well, if you think it’s fine, why have I heard it’s a bad pack?

And so on, whenever he opened his mouth, which he did a lot: to my everlasting regret, I devoted far more space in my journal to Rubin than to Geoff and Molly. With the sun setting, he yanked six Old Milwaukee tallboys from his pack and chugged them in quick succession. He crunched the empties into makeshift candleholders. As the rest of us crawled into our bags, he began to celebrate the Sabbath.

In what seemed a trance, he chanted, wailed, and danced in the middle of the shelter for one hour, then two. Then beyond two. At 9:30, Greg stopped him: “Are you almost through?” Rubin nodded, then went right back to it. Shortly after ten, when he’d paused to wolf down some bread, I told him he’d have to stop. “These people are trying to sleep,” I said, nodding toward the others. “There’s got to be a way you can pray to yourself.”

Rubin brushed me off. “They’re probably sleeping right through it.”

From the darkness of the shelter’s west wall, Molly yelled, “I’m not sleeping through it!” A chorus backed her up.

Morning came. Rubin needed no coffee to get up to speed. Throughout his babble, Geoff and Molly—who wrote in their journal that they’d “had a very poor night’s sleep due to the noise pollution”—treated him with quiet tolerance, never rising to his bait, just letting him be.

Still, they beat us out of camp. We caught up with them that afternoon as they took a break at a road crossing, chatting about the strange night we’d shared and our relief that Rubin was northbound. Greg and I pushed on but reunited with the other four southbounders that evening at a Dartmouth Outing Club bunkhouse. Geoff had hitched to a store for beer, and we all sat around the house’s kitchen table, drinking and talking, late into the evening—about their layoffs, their plans for grad school after reaching Georgia, and, not least, Rubin.

The next morning, we all took a two-mile detour to a restaurant for the hiker’s special: six pancakes, four pieces of sausage, coffee, and juice for $5. We lingered, talking and laughing, long after we’d gorged ourselves. Back outside we split up: Greg and I decided to hike an old section of the AT, while the others backtracked to the rerouted trail.

We watched as they hitched a ride from a pickup and, waving from its bed, motored off for the trail crossing. We expected to reunite with them that night. But we covered close to 16 miles that day, far more than they did. We didn’t see them again.

A few days later, we caught up with Muskratt at Vermont’s Happy Hill shelter. We’d followed his register entries from Maine, and he proved an affable companion, at ease in the woods after working at fish camps close to the Canadian border.

Near Manchester Center, Vermont, both Muskratt and Animal pulled ahead of me, and no matter how far or fast I hiked, I couldn’t catch up; they seemed to stay a shelter ahead through the rest of New England, until, after a hell-for-leather sprint, I managed to catch Muskratt just inside New York State. I hiked with him for several days, lost him near the New Jersey border, caught him again near Palmerton, Pennsylvania, lost him again. Greg left notes in shelter logs asking where I was, but he stayed just ahead of me.

Meanwhile, Geoff and Molly enjoyed late starts and lunch breaks that stretched into overnights. I left hellos to them in logbook entries, and sometimes, I learned much later, they replied. By the time I reached central Pennsylvania, they trailed me by eight days.

A thousand miles south of Katahdin, I crossed the Susquehanna River and walked into the old ferry town of Duncannon, Pennsylvania, following the trail’s white blazes on telephone poles up High Street past churches, a hardware store, and simple, sturdy houses on well-tended lawns. The next day, I sweated four steep and rocky miles up Cove Mountain to the Thelma Marks shelter.

Another southbounder was already there: Marcus Macaluso, a.k.a. Granola, of Kennett Square, Pennsylvania, a long-haired, deep-thinking Grateful Dead fan, 18 years old, who carried bongos in his pack and left clever register entries that I’d enjoyed for weeks. We wound up talking past 11 p.m.

Both of us slept late and lounged at Thelma Marks, drinking coffee, until close to noon. Any hopes for respectable mileage already shot, we settled for an easy seven-mile stroll to the Darlington shelter.

At this point a chase was under way. Three southbounders—Brian “Biff” Bowen and his wife, Cindi, of Amherst, Virginia, along with Gene “Flat Feet” Butcher, a retired soldier I’d camped with in Vermont—were trying to catch Geoff and Molly, who were trying to catch up with Muskratt, who was now just behind me. I was still trying to catch up with Greg, who had left word in Darlington’s register that he planned to end his hike in Harpers Ferry, West Virginia, a few days to the south. “Hope to see you before I get off,” he wrote.

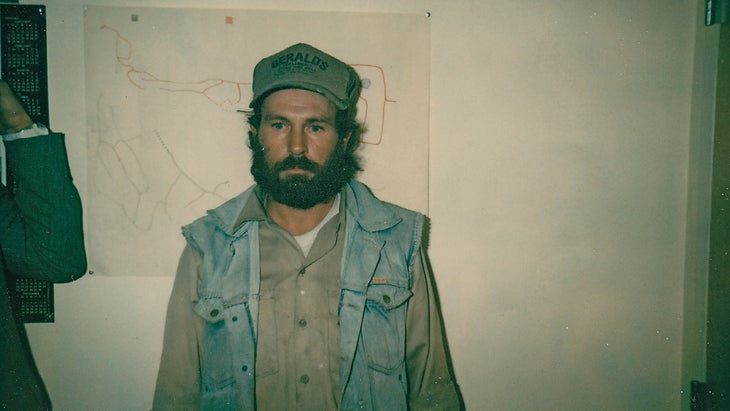

That same day—September 5, 1990—a 38-year-old farmhand left his cabin on a South Carolina tobacco spread, caught a ride to the nearest Greyhound depot, and bought a one-way ticket north. He was a short, stocky man, considered smart and hardworking by his bosses. They’d also remember him as rootless, quiet to the point of secrecy, and prone to lengthy, unexplained absences. The shack he left behind was piled with garbage and empty beer cans.

A day later he stepped off a bus in Winchester, Virginia, and embarked on a zigzag course of hitched rides—west to Romney, West Virginia, north into Maryland, northeast to Gettysburg, Pennsylvania—until, six days after leaving the farm, he walked into a library in East Berlin, Pennsylvania, halfway between Gettysburg and York, looking for hiking maps. A librarian suggested he try the York branch, wrote directions, and asked that he sign the guest book. He put down Casey Horn.

His name was really Paul David Crews, and he was a suspect in a murder. Four years earlier, on July 3, 1986, a woman had offered him a ride home from a bar in Bartow, Florida. She was later found naked and nearly decapitated on an abandoned railroad bed. Not long after, according to law-enforcement records, Crews had turned up at his older brother’s place in Polkville, North Carolina, driving the woman’s bloodied Oldsmobile. With the law closing in, his brother gave him a lift into the country, and he took off running. The police recovered the car, along with Crews’s knife and bloody clothes, but found no sign of him.

Since then he’d laid low, avoiding attention and revealing little of his past, which had been troubled from the start. Abandoned in childhood, he was adopted at age eight by a couple in Burlington, North Carolina, but he ran away frequently. He joined the Marines in 1972 and married in January 1973. Became a father the following month. Attempted suicide, went AWOL, and got discharged from the corps. Divorced in 1974. Bounced around.

In 1977, he turned up in southern Indiana, where he worked a string of dead-end jobs and met his second wife. One morning he crawled into bed behind her and held a bayonet to her throat. They divorced, too.

He wandered back to Florida, where he picked oranges each spring until the homicide in Bartow—a crime he was formally charged with on July 7, 1986. So the police thought Crews might have killed before. And now, late on the afternoon of September 11, 1990, he found his way to the Appalachian Trail.

At the time, the AT followed 16 miles of paved road through Pennsylvania’s Cumberland Valley—a shadeless hike, hard on the feet. The trail’s caretakers had worked for years to reroute the footpath into forest they had acquired piecemeal. On this afternoon, the ATC’s Karen Lutz was surveying one such property when she noticed a bearded man plodding up the road behind her.

She was a stone’s throw from the Pennsylvania Turnpike and figured him for a hitcher between rides, a drifter. No chance he was a hiker: he wore a flannel shirt, jeans, and combat boots, had a small rucksack on his back, and carried two bright red gym bags, each emblazoned with the Marlboro logo. He kept his head down as he trudged past, headed north toward U.S. 11.

Two hours later, Lutz drove north on the trail, following its blazes through several turns. Well north of 11, she encountered the stranger again. So he was hiking, she realized. He wasn’t far from the spot where the AT veered from the road and into the trees. If he hustled, he might make the Darlington shelter, little more than three miles away.

Lutz drove on, unnerved. Something about the man—his filthiness, his clothes, his joyless progress—filled her with dread. She didn’t know that the stranger carried a long-barreled .22-caliber revolver, a box of 50 bullets, and a double-edged knife nearly nine inches long. She didn’t know he was among Florida’s most wanted fugitives. Even so, Lutz, herself a 1978 through-hiker, decided that Darlington was a place she most sincerely did not want to be.

For years she would be haunted by that moment, by “tremendous guilt over the fact that I had seen him, and that I had sensed an evil aura coming off him.

“I know that sounds wacko, but that’s exactly what I felt,” she says. “And I didn’t do anything.”

Earlier that day, Geoff and Molly had broken camp at the tiny, squalid Peters Mountain shelter north of the Susquehanna River. They were almost halfway through their hike now, and ambitious days came comfortably, though they didn’t make them a habit. They continued to dawdle through meals. They lounged on any rock with a view. They even paused to do some counseling. “We reached the Allentown shelter for breakfast,” Geoff wrote on September 6. “There we met Paul, whom we talked with quite a while. He is a 15-year-old who was kicked out of his house. We talked about some different ideas for him to try.”

Along the 11 miles to Duncannon, they encountered a section hiker, Mark “Doc” Glazerow of Owings Mills, Maryland, who joined them at a pizza parlor in town. His companions were still eating when Glazerow announced that he had more hiking to do, wished them luck, and groaned his way up to Thelma Marks.

Geoff and Molly walked two blocks to the , the crumbling fossil of a once grand inn. In 1990 as now, its bar served wonderful burgers and cheap draft beer, but even at $11 a night, the 23 peeling, spider-infested rooms upstairs were only so much of a bargain. They shared just three baths.

Still, those rooms had mattresses. The hikers unpacked their gear and called their parents, discussing their planned reunion in Harpers Ferry to celebrate making it halfway. Better bring soap and brushes, Geoff told his mother, so that we can scrub the smell out of our packs. Glenda Hood promised to bring two pumpkin pies, his favorite.

One more thing, Geoff said—we have something to tell you when we all get together. “There’s always been a lot of speculation about what that was going to be,” his younger sister, Marla Hood, says. She thinks they planned to announce their engagement.

Biff and Cindi Bowen slowed as they approached the lean-to’s rear. The clearing was dead quiet. An hour later they were back in Duncannon, phoning the state police.

That night, while feasting on shrimp and mushrooms, the couple signed the Doyle’s register, countering a previous hiker’s claim that he was the last of 1990’s southbounders.

“Hey Greenhorn you most certainly are not the last entry of the season,” Geoff wrote. “As you can’t read this we’ll tell you when we catch you! As we hear it we’re about mid-slip of the southbounders moving down—oops getting food on the book. Good food too; time to go—Clevis & Nalgene.”

In the morning—Wednesday, September 12, 1990—they met Molly’s elderly great aunt and two other relatives on the town square, then accompanied them to lunch at a nearby truck stop. Afterward, they picked up mail, stopped at a small grocery, and, at 3:45 p.m., followed the trail into the woods and up Cove Mountain.

The climb over lichen-flaked stone and loose scree ended at Hawk Rock, a promontory offering a sweeping vista of the town, rivers, and rolling farmland below. From there they faced an easy two miles of ridgetop to Thelma Marks—which waited, dark and droopy, its back to the AT, at the bottom of a steep 500-foot side trail.

Geoff and Molly likely arrived there sometime after 5 p.m. The graffiti-carved plank floor slept four or five comfortably, eight in a pinch. They would have had plenty of room to unroll their sleeping gear and spread out a bit.

Sunset came at 7:22 p.m., but the shelter was hunched against the mountain’s eastern flank, in the shade of the ridgetop.

Night fell fast.

Geoff and Molly most likely died between five and seven the next morning. Little else about the event is certain. Were they in trouble from the moment they met Crews? Unknown. Were they attacked as they slept? Unclear. Did they have a conversation with him? The killer’s own words, to others he met in the days that followed, suggest they talked and that he stole their story along with their gear: he said he’d started hiking in Maine around the first of June and was trying to catch up with Muskratt.

Jerry Philpott, the Duncannon lawyer who represented Crews at his 1991 trial, says he believes the couple reached the shelter first. “They were settling down for the night,” he says. “It was summer—it would have been pretty light. He came upon the scene, and something happened.

“This is a brain on cocaine and a quart of Jim Beam,” Philpott says of Crews. “He would take a quart of Jim Beam and a cigarette pack full of powder cocaine, and that’s how he would hike.”

Crews shared little information with him, Philpott says. “He never wanted to talk about this incident, or any of his alleged murderous incidents.”

Indeed, Crews offered only monosyllabic responses to police, said next to nothing in court, and has described to no one, as far as is known, why things took such a horrible turn at Thelma Marks. He did not respond to several interview requests for this story.

Bob Howell, a Pennsylvania state police investigator at the center of the inquiry, offers a straightforward take. “He went on the trail looking for an opportunity,” he says. “Bingo. That’s it, as far as I’m concerned.”

Jim LaRue’s explanation is almost as cut and dried. “He happened to fall on these two kids and I’m sure saw Molly as a rape prospect.

“Molly was a strong girl,” he says. “I wish she had had the strength to overcome him, and even if she had had to kill him, that would have been all right with me—just to protect herself and maybe save Geoff. But that’s not the way it played out.”

This much is known: later in the day on September 13, Crews returned to the trail and hiked north into Duncannon without his red gym bags. Now he wore a big green Gregory.

He hitched a ride east to Interstate 81 and got at least one ride south before rejoining the trail in the next county, far from Thelma Marks. He walked south from there, assuming the guise of a through-hiker.

At the same time, the trio of southbounders chasing Geoff and Molly walked into Duncannon. Gene “Flat Feet” Butcher decided not to dally and hiked up Cove Mountain shortly after Crews had descended the same path. Peering down the steep mountainside toward the invisible Thelma Marks shelter, Butcher decided not to stop in and hiked on to Darlington. There he found the shelter littered with trash—including an empty red gym bag, a discarded bus ticket, and a library note written to someone named Casey Horn.

Back in town, Biff and Cindi Bowen retrieved a mail drop and stuffed themselves on pizza, ice cream, and beer. It was close to 5 p.m. when they started climbing and about six when they reached the turnoff.

Cindi, an elementary school teacher, and Biff, a jeweler, knew they were close on Geoff and Molly’s heels. They planned to celebrate Biff’s upcoming birthday at Thelma Marks and were excited that they might do so with a couple they’d followed for nearly three months. “We knew they were good people,” Cindi says, “because we’d been reading their entries.”

But they slowed as they approached the lean-to’s rear. The clearing was dead quiet. An hour later they were back in Duncannon, phoning the state police.

That night, detectives who’d never set foot on the trail struggled for three hours to reach Thelma Marks. “I think most of the conversation was curse words,” recalls Pennsylvania state trooper Bill Link. “We were in dress shoes. It was dark.” The crime scene unfolded piece by piece in the beams of their flashlights. Geoff was lying in a back corner, his head on a makeshift pillow. “At first glance,” Link wrote in his report, “one would be led to believe that the subject was asleep.”

“At the other side of the lean-to,” he wrote, “the body of the female was observed laying face down in a pool of blood.”

It took another four hours to maneuver a pair of all-terrain vehicles up the mountainside on an old logging road, troopers chopping down trees to clear the way, so that the bodies and evidence could be removed.

After that the investigation proceeded rapidly. From Karen Lutz, they learned of the stranger with the red gym bags. They found one such bag at Thelma Marks, the other at Darlington. The library note Flat Feet had discovered gave them a name.

Glenda Hood, at home in Signal Mountain, Tennessee, switched on the radio the morning of September 14, just in time to hear a news report that two hikers had been murdered near Duncannon. Geoff had called from there three days before.

She knew her son was careful. In the past, when they had discussed someone meeting a bad end in the outdoors, he’d told her, “He either didn’t know what he was doing, or he wasn’t doing what he knew he should be.”

Just the same, she phoned Jim LaRue, up in Shaker Heights, Ohio, and told him what she’d heard. He burst into tears. “I was sure it was them,” he says. “I just knew.” He saw Molly’s mother, Connie, pull into the driveway with a load of groceries. He walked out and told her, “I think this is going to be the longest day of our lives.”

It was, and the days that followed were not much better. The families arranged for memorial services while police searched for the killer. Geoff was laid to rest near his home in Tennessee, in a plot overlooking Signal Mountain. Molly’s body was transported to a funeral home outside Cleveland, where the LaRues found her on a mat, covered with a sheet. The funeral director told them, “I thought you might like to hold her.”

Jim, Connie, and their son, Mark, three years older than Molly, dropped to the floor and wrapped their arms around her. “It was one of the most wonderful gifts,” Jim says. “She looked like she was asleep. It reminded me of when she was little and scared and couldn’t sleep, and going into her room to give her a hug.”

I was still on the trail, hiking in Virginia’s Shenandoah National Park, when a pair of day-hikers told me a couple had been killed on the trail up in Pennsylvania five days before. A phone call home gave me their names.

Granola had pulled ahead of me, and I lay alone in a shelter that night, stunned and scared. I’d never known a murder victim. Until then I’d been a typical suburban American who figured that violence usually came by invitation. I’d hear of a crime and do a little calculus to separate myself from the victim: I wouldn’t hang around a crack house. No way would I walk that street at three in the morning.

This time the math didn’t work. I couldn’t claim to know Geoff and Molly well, but they seemed far savvier in the woods than I was. They were traveling as a pair, too, which was considered common sense. They were certainly more patient than me, and far better equipped to defuse trouble. And they were so damn nice, even to Rubin.

If chaos could find them, I realized, it could find anyone. The senseless happened. The universe had no plan. Their deaths seemed a terrible accident of time and geography. Biff Bowen had the same frightened thought: “Had we hiked a little faster, it might have been us.”

Granola and I reunited a couple of days later. In Waynesboro, Virginia, we ran into an older southbounder, George Phipps, whom we’d camped with in Maryland. The killings dominated our conversation.

“Some of Geoff and Molly’s register entries impressed me so much, I wrote them down,” George told us. He flipped through his trail journal, started reading.

Last evening I whispered “I think there’re less bugs.”

This morning, BRING ON THE SLUGS.

When we had that conversation, Crews was in the custody of federal park rangers in Harpers Ferry, having been captured a few hours before as he walked a bridge across the Potomac. A hiker who’d embarked on a freelance search for the killer recognized Geoff’s pack on his back and sounded the alarm.

Crews was jailed, pending trial. Lawmen in Pennsylvania began putting together their case.

The families grieved. Glenda Hood, a pediatric nurse, threw herself into caring for ailing children. Connie LaRue, also a nurse, volunteered at a hospice on the shore of Lake Erie. The women talked often. They became close.

Jim LaRue found comfort in an idea offered by one of Molly’s college friends—that Molly, ever artistic, was now adding her touch to each evening’s sunset. “From that day forward,” he says, “there’s not a day that goes by that I don’t see a spectacular sunset and think: Ah, Molly’s at work.”

Strange as it sounds, the fact that family and friends were thrust into the unexpected role of defending the Appalachian Trail might have helped them cope. “We kept getting comments like, ‘Well, do you feel the trail is too dangerous to use?’ and ‘Should it be shut down?’ ” Jim says. “That’s when Molly’s voice would come up and tell me, ‘If you ever let my death be an excuse for anything happening to the trail, I’ll never forgive you.’

“Mol was where she wanted to be, doing what she wanted to do, caring about what she wanted to care about, having fun, and meeting and enjoying so many people,” he says. “To die doing something you love is not the worst thing in this life. There are no guarantees.”

Glenda Hood climbed Cove Mountain on the first Mother’s Day after the murders. The trail was abloom in wildflowers—Jack-in-the-pulpits, native columbine—which almost seemed a message, a gift, from Geoff and Molly. She ventured into the clearing.

“I expected it to be a dark, sinister place, and it wasn’t,” she says. “The sun was coming down through the trees, and it was a peaceful place, despite what had happened there.

“I consider that Geoff and Molly were murdered in God’s cathedral,” she says. “If someone were murdered in God’s cathedral, then murder could be committed anyplace.”

Testimony in the trial started three days after Glenda’s hike, on May 15, 1991. The state presented 60 witnesses and 158 pieces of evidence that spun an inescapable web around Crews: He’d been arrested wearing Geoff’s pack, boots, and wristwatch, and he was carrying both murder weapons. He’d left his own gear at the scene, some of which was traced back to the tobacco farm in South Carolina. DNA linked him to Molly’s rape. He was convicted and sentenced to death by lethal injection.

I was in the courtroom. Unable to shake the confusion I’d felt upon learning of the deaths, nagged by a need for explanation, I’d begged off work to return to Pennsylvania. The proceedings offered only roundabout, unsatisfying clues as to why the killings had happened. During the trial’s penalty phase, a psychiatrist appearing for the defense testified that Crews had a personality disorder and that his consumption of whiskey and cocaine had triggered “organic aggressive syndrome.” The doctor described the condition as “a short period of time after taking cocaine, maybe an hour or two, when a person can become violent.” That was as much explanation as we got.

But the trial was not without its rewards. Hikers were on hand to testify, and others, like me, had simply shown up. Some of us formed lasting bonds with Geoff’s and Molly’s families. So it was that when Biff and Cindi finished their hike that summer—having avoided shelters every night—Glenda Hood picked them up at the trail’s southern terminus at Springer Mountain, Georgia.

And in June 1992, when Geoff’s sister, Marla, set out to finish the couple’s hike, I went along for her first week. We started south from Boiling Springs, Pennsylvania, our pace modest in the Geoff and Molly tradition, reaching Pine Grove Furnace State Park, near the trail’s midpoint, on our second day out. We ate lunch at the top of a fire tower and shared a shelter with a pile of northbounders on day three, visited an emergency room when Marla pulled a knee on day four, and reached the Maryland line on day six.

Others joined Marla after me—Kansas friends, a couple of hikers the ATC had lined up, and the ATC’s chief spokesman, Brian King—before an infected blister forced Marla off the trail in Virginia.

Ten years later, in September 2000, I learned from Karen Lutz that the Thelma Marks shelter was to be replaced. I drove to Duncannon, slept at the Doyle, then swore my way uphill to the clearing. Lutz was already there, watching a crew from the Mountain Club of Maryland finish the new shelter, which was built of beams from a century-old barn. We stood together under a tall sassafras tree, songbirds chatty in its branches, and eyed the careworn and mouse-infested Thelma Marks for the last time.

“This event really seemed to mark the end of the trail’s innocence,” Lutz told me. In the years after the killings, hikers were more apt to bring pepper spray along with their freeze-dried meals and to take dogs along. The ATC had become far more sensitive to reports of disquieting conduct on the trail, and quicker to intervene. Earlier in the year, the organization had even published a 176-page handbook called .��

“This week is always a tough one,” Lutz said. “There’s a certain quality of the light this time of the year, and the temperatures suddenly get cooler and the humidity drops off, and it all comes right back.”

Not long after, the crew removed the old shelter’s corrugated metal roof, dismantled its log walls, and sawed them up. They burned the wood in a bonfire, scattered the rock foundation. It was an exorcism as much as a demolition. When they finished, nothing remained of the old hut but a bald patch in the forest floor, not even its name. They called the new place the Cove Mountain shelter.

The forest got busy reclaiming the footprint.

Fifteen years have grayed the new shelter’s wood. It blends comfortably, unobtrusively, into its setting, has become one with the surrounding timber.

Those same years saw Connie LaRue fall ill with cancer and spend her final days in the hospice where she volunteered. She awoke from a dream near the end to report that she’d seen Molly waiting for her. Glenda Hood held her hand shortly before she died in July 2006.

Glenda continues to grieve not only Geoff, but also the future he might have had with Molly. It’s a loss she emphasized at a December 2006 hearing where Crews’s death sentence was replaced with life in prison without parole. “That day half my future was taken from me,” she told Crews. “I have missed his wedding to Molly. I have missed seeing them share their lives together. I have missed their children, who would be my grandchildren.”

“Geoff and Molly were murdered in God’s cathedral,” Glenda Hood says. “If someone were murdered in God’s cathedral, then murder could be committed anyplace.”

Biff and Cindi Bowen have divorced, but their son, Mason, took on the trail in 2010. Like his parents, he was a southbounder. Flat Feet met him at Springer Mountain.

Karen Lutz has achieved an uneasy peace. “There isn’t a week that goes by that I don’t think of that, 25 years later,” she says, adding: “It’s better than it used to be—it’s no longer every minute, or every hour.”

Jim LaRue has lost Connie, whom he’d known since both were five. But he later found Barbara, who’d lost her husband. They live in a home on rolling woodland that they share with school groups exploring the natural world. “I want to spend my time caring about things my daughter cared about. I think that’s how I can best honor her memory,” he says. “If she knew I was wallowing in grief, she would kick my ass. She would say, ‘If you love me, get over it. Get over it, Jimmy.’ ”

His statement to Crews at that 2006 hearing reflected, he thinks, what Molly would have wanted. “Paul, I am here today to offer forgiveness for what you have done,” he told his daughter’s killer—at which point, he says, Crews locked eyes with him and held the connection. “I wish that you and I can now find peace.

“Molly had decided to devote her life to working with troubled children, like you certainly were,” he told him. “Paul, I think it would be great if you could pick up where Molly left off, starting with yourself. Help the Mollys of this world learn who you are, and try to enlist the help of other inmates to help in this effort. You are a gold mine of critical information that needs to be unearthed.”

“Peace be with you, brother,” he said in conclusion. “Peace be with you.”

This past spring, I climbed again to the clearing. In the quarter-century since my first visit there, through-hiking had mushroomed in popularity: in 1990, the ATC recorded more than 230 completed end-to-end treks, just eight of them southbound; last year, the total had grown to 961. Though a few well-publicized homicides have occurred on trails or parklands near the AT since Geoff’s and Molly’s deaths, just one—the unsolved 2011 killing of an Indiana hiker, Scott “Stonewall” Lilly, near a shelter in Amherst County, Virginia—has claimed someone actually walking the path.

My visit got me thinking of my 158 days and nights on the AT, the people I’d met, the friends I’d made, and when I got home I phoned Animal to revisit our adventures together. It had been 21 years since I’d last seen him, when I’d attended his wedding. He has a pair of teenage sons now. He’s also a Southern Baptist minister.

We read our trail journals aloud, laughed over our descriptions of Rubin, then turned to the subject of Geoff and Molly. Greg was confident that what had happened to them was part of a divine architecture, that the world’s sin, its evil, is no accident—that everything is “part of God’s sovereignty.”

Including his own hike. When he left Katahdin, he said, he had not been a good Baptist—which would explain all that beer he drank with me. But he took a step toward the righteous path late in his hike, he told me, and he could remember the night it happened: Wednesday, August 28, 1990, at the Thelma Marks shelter.

He reached the hut two weeks before Geoff and Molly. He was alone there. A storm rumbled in the distance as he pulled a Bible from his pack, along with his journal. “The lack of direction in my life was due to my leaving God,” he wrote, “but He loves me and I feel a new strength. I pray that I can retain this and use it in my life.”

A few minutes later, the weather hit. The wind rose to a sustained yowl, shredded the treetops, racked the old lean-to, seemed to be swelling toward a terrible end. Then it fell quiet. “I thought a tornado was on the way,” Greg wrote. “I was really scared, but you have to keep the faith.”

The next morning, he stepped out of the shelter and into the clearing. Sunshine splayed through the trees to dance at his feet. Birds trilled. The air smelled fresh, and all about him the woods seemed renewed. And he recognized the place as a little piece of paradise.

Earl Swift is the author of five books, including .