Walking uphill is harder than walking on level ground. Walking downhill is easier—until it’s not, as anyone who has walked down a long, steep mountain slope eventually discovers. The precise relationship between how fast you walk, how steep your trail is, and how much energy you burn turns out to be less obvious than you might assume, which is why researchers at the United States Army Research Institute of Environmental Medicine decided to develop an equation that captures these nuances.

Lots of researchers have tackled this question over the years, most notably the Italian physiologist Rodolfo Margaria back in the 1930s, so the basics are well understood. When you head uphill, your energy expenditure is directly proportional to the steepness of the grade. When you go downhill, in contrast, your energy expenditure initially decreases but at grades of about -10 percent it reaches a minimum then starts to increase again.

But finding a single equation that captures this pattern has proven to be difficult. In the new paper, which is , the military researchers decided to take an existing equation that works on level ground—the Load Carriage Decision Aid—and add a term to adapt it for uphill and downhill calculations. They pulled existing data from 11 different studies and used that data to fine-tune their equation, with the result that it outperformed four previous calorie estimation equations.

For the record, the equation gives you energy expenditure (EE) in watts per kilogram of body mass, as a function of walking speed (S) in meters per second and gradient (G) in percent:

EE = 1.44 + 1.94*S^0.43 + 0.24*S^4 + 0.34*S*G*(1-1.05^(1-1.1^(G+32)))

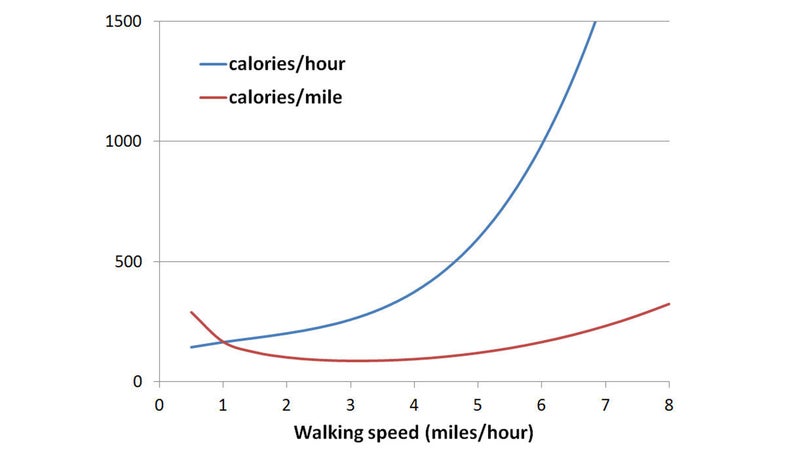

In case that’s a little hard to visualize, let’s take a look at the equation’s basic behavior. With a few adjustments to express the energy expenditure in calories and the walking speed in miles per hour, and assuming a hiker weight of 150 pounds, here’s a basic graph for level ground (G = 0):

The primary output of the graph is the blue line in calories per hour. The faster you walk, the more calories you burn per hour, which is fairly obvious. The line gets progressively steeper, reflecting the fact that once you get up to speeds beyond about 6 miles per hour, walking is very inefficient (which is why you find yourself naturally breaking into a jog).

That’s not the only way to think about that data, though. Instead of calories per hour, you can plot calories per mile (in red above). Here you see that the number of calories it takes to cover a mile is somewhat constant. If you go slow, your rate of energy burn decreases but it takes longer to cover a mile; if you go fast, you’re sizzling through calories but you finish sooner. Between about 2 and 5 miles per hour, which encompasses most people’s comfortable walking paces, those two factors roughly balance each other and calories per mile stays pretty flat. Of course, if you’re either really dawdling or racewalking, things gets significantly less efficient.

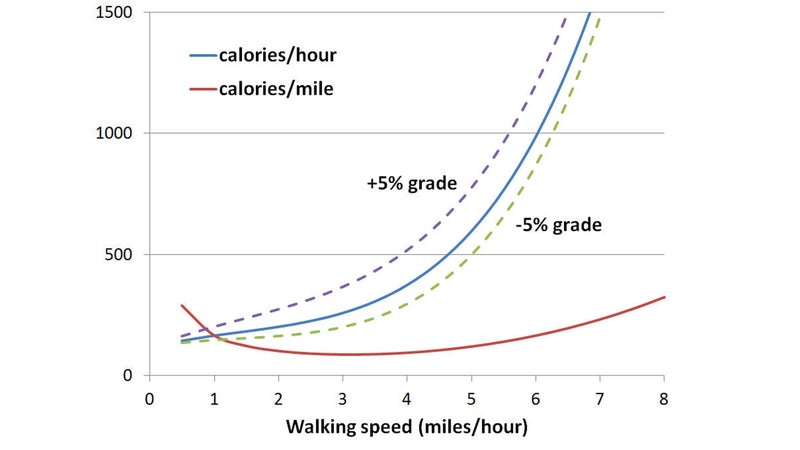

What happens when you add in some hills? The obvious answer is that your energy expenditure increases on uphills and decreases on downhills. Here’s what that looks like for a 5 percent grade either up or down:

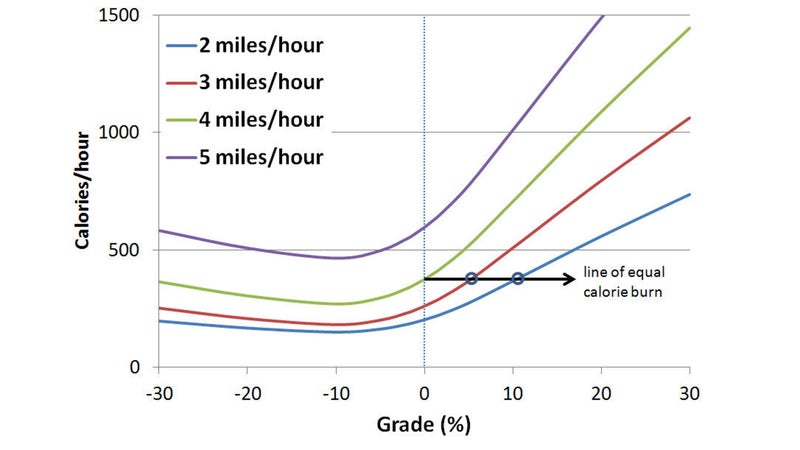

As you can see, the change in energy expenditure isn’t symmetric for climbing versus descending a 5 percent grade. To get a clearer view of how grade affects energy expenditure, it’s helpful to switch and instead plot it as a function of grade. The graph below shows calories per hour as a function of grade, for four different speeds:

Here you can see that going uphill incurs a steep cost. Going downhill, on the other hand, gives you a more modest benefit initially, and then energy expenditure bottoms out somewhere between -5 and -10 percent grade, then starts increasing again. If you’re choosing a route through the mountains, look for downhill routes that get close to that sweet spot.

The military is interested in this data for fairly obvious reasons. They need to estimate how long it will take to cover a given distance over variable terrain, how hard it will feel, and roughly how many calories it takes, and they may also want to plot the most efficient route. Last year, I wrote about the Pandolf equation, a similar estimator that takes the weight of your pack into account, but it isn’t able to handle downhill slopes—a fairly significant limitation that this new equation addresses.

In theory, backpackers have similar interests, but few bother to model the energy requirements of their routes in that much detail. Instead, the new equation is mainly interesting to me as a way of getting a rough estimate of the relative difficulty of hiking at different slopes. The horizontal line on the graph above tells me that if I’m used to hiking at 4 miles per hour on level ground, it’ll take a similar effort to go 3 miles per hour up a 5 percent slope, and 2 miles per hour up a 10 percent slope. If you want to play around with some of these parameters yourself, try plugging some numbers into the calculator below.

One final note: it’s not necessarily clear that keeping your energy expenditure constant over hilly terrain is actually optimal. In cycling, thanks to the nonlinear effects of aerodynamic drag, it makes sense to push a little harder on the uphills (where drag is less important because your speed is lower) and back off on the downhills (where you’d have to work disproportionately hard to overcome the high-speed drag). There’s that runners instinctively do the same thing, pushing harder than they “should” on uphills and recovering on downhills. Is this a tactical error, or are they responding to other cues (like the pounding your muscles take when running fast downhill) that make a more uneven effort profile more optimal? If it’s the latter, does the same apply for hiking?

With those caveats and as-yet-unanswered questions in mind, here’s based on the modified Load Carriage Decision Aid. Have fun!

My new book, , with a foreword by Malcolm Gladwell, is now available. For more, join me on and , and sign up for the Sweat Science .