In March 2012, the Pacific Crest Trail changed for good when , about her 1995 thru-hike of the trail, hit shelves and quickly became a New York Times bestseller. In 2014, Reese Witherspoon adapted and starred in the . From 2013 to 2018, PCT applications nearly quadrupled.

But Wild wasn’t the only thing that transformed the trail that March. The same month, thru-hiker named Ryan Linn quietly released an iPhone application . It took the entire set of tools needed for thru-hiking—a map, compass, guidebook, and water reports—and consolidated them into a single virtual location. It functioned off-line and crowdsourced updated information about trail conditions and campsites when online. Such an app might have been inevitable, but for ultralight-obsessed thru-hikers, it was a revolution.

Linn’s timing couldn’t have been more perfect. In the last three years, the app has been downloaded 337,000 times, and in 2018, found that 85 percent used the app. found that, for the first time, more AT hikers found Guthook helpful than David Miller’s The A.T. Guide (a.k.a. the Awol Guide), the longtime king of AT guidebooks. What started in 2010 as a passion project is now a company that employs five people full-time and has mapped more than two dozen long trails around the world.

But as the the app’s empire continues to grow, many thru-hikers worry about its unintended consequences. They see themselves and fellow hikers depending on their phones to decide where to sleep and eat and to discover exactly how far, down to the tenth of a mile, they are from those places. They fear that American thru-hiking, once the ultimate test of self-reliance, is no longer as wild as it once was.

While attending Vassar College in 2002, Linn joined an outdoors club. The upperclassmen decided that the new recruits needed intimidating nicknames. One day, Linn and two other club members were driving past a hunting and fishing store and pulled over to wander the aisles for inspiration. Linn became “Guthook,” and it stuck through college and afterward, when he hiked the AT in 2007 and then the PCT in 2010.

It was while hiking the PCT that Linn met Paul Bodnar, a guidebook author who was collecting GPS data on trail with the intent of updating a PCT guide he published in 2009. In the era of “There should be an app for that,” it didn’t take long for the two to start talking about what a smartphone-based guide would look like. “We figured it would be something for us to do on the side, in between seasonal work,” says Linn, who since college had been doing various trail-crew and outdoor-education jobs.

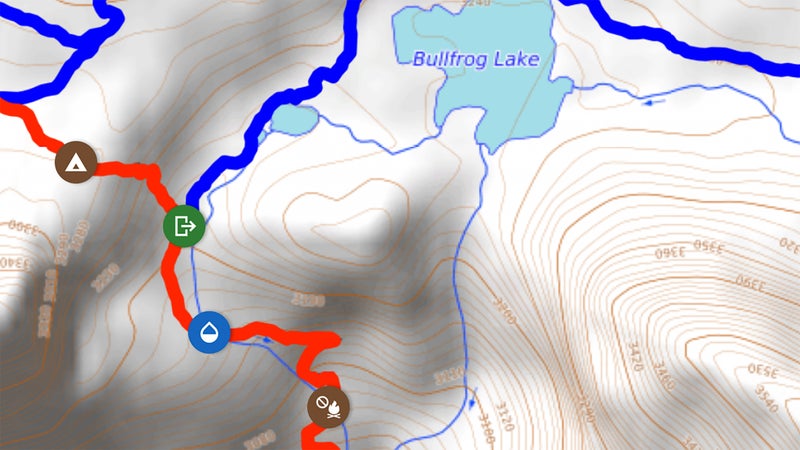

After they finished their hike, Linn spent the next year and a half using the GPS data Bodnar had collected to create the first version of Guthook Guides, learning to code as he went. Visually, the app looks similar to the paper topo maps hikers have used for decades. Virtual icons along the trail designate campsites, water sources, intersecting roads, and trail-town information. But unlike paper maps, Guthook Guides is GPS enabled, and users can click on an icon to learn more or add a comment. The ability to leave comments, in particular, made Guthook Guides more than a guidebook. Hikers could tell other users whether a water source had gone dry, the quality of a campsite, and the friendliness of local businesses.

After the 2012 release, the app made just enough money for Linn to pay a friend to collect data while hiking the Appalachian Trail in 2013. (The app is free to download, but users must then purchase guides for each trail.) The AT guide was released the next year. In 2015, Guthook Guides became available on Android phones. By then, Linn and Bodnar, the app’s cocreators, understood that Guthook Guides was no longer a side project. They went all in.

A sense of surviving in the wilderness is a major reason why a 2,000-mile hike is more than just a feat of athleticism. Taking a wrong turn, getting lost, navigating back—all that misadventure and the intellectual challenge of sorting it out makes for better stories than does walking in a straight line dictated by an app. Yet thru-hiking the PCT last year, I had to stop myself from checking the Guthook app as often as every hour. At one point, my hiking partner even instituted a no-Guthook rule, with the hope that we’d reclaim some sense of agency over our endeavor. Our self-imposed app ban didn’t last, because pretending like we didn’t have this all-knowing resource in our pockets felt somehow inauthentic. Especially when most everyone else on trail was embracing it as reality.

It’s hard to understate the impact that Guthook has had on the experience of thru-hiking. I talked to nearly a dozen hikers and trail managers who all seemed simultaneously concerned that the app enables hikers to lose self-reliance and awareness of their surroundings but couldn’t deny the app’s supreme usefulness. Eric Lee, for example, has taken time off from his job as a software engineer every year since 2002 to hike a different section of the PCT. The 48-year-old completed the final segment last fall. Over that time, Lee witnessed smartphone apps slowly become ubiquitous in long-distance hiking. There was a PCT app called Halfmile that used GPS to identify your location on its companion physical maps (the developer discontinued the app this year). Later, offered its own GPS-enabled maps for multiple thru-hikes. But none of them took off like Guthook Guides, which grew to dominate the space. “Guthook does make for a very different experience,” says Lee. “I can’t say it’s better or worse, it’s just different.”

Lee compares the impact of Guthook Guides to what Google Maps has done for driving. “We no longer have to think about landmarks and turns and street names. We just type our address into the phone and press go,” he says, noting that it undoubtedly makes thru-hiking an easier, more stress-free experience. But because of the app, he sees more hikers today who are not as viscerally connected to the trail. “They’re walking from waypoint to waypoint. It’s just a set of numbers.”

“You can now call an Uber or Lyft into town if it’s going to rain. It has altered the way people do their hikes.”

This effect has led to some pushback against the app. “I’ve encouraged people to not use it,” says Lucas Weaver, a 29-year-old fiber-optic technician who used Guthook Guides while hiking the Continental Divide Trail last year. “I’m not saying don’t get it, I’m saying don’t let it dictate, don’t rely on it.” Weaver is glad he hadn’t yet downloaded the app when he hiked the AT in 2015. “Being out there without any guide or technology makes it more adventurous,” he says.

The app’s popularity has coincided with the use of phones creeping into trails more generally. Now hikers have Instagram accounts to update with selfies, blogs to write, and loved ones to keep in touch with. “There is no question that people are using their devices more and more on the Appalachian Trail,” says Morgan Sommerville, southern regional director at the Appalachian Trail Conservancy. “You can now call an Uber or Lyft into town if it’s going to rain. It has altered the way people do their hikes.” Effie Drew, a 26-year-old nanny who has hiked all three major trails, now sees people regularly checking for cell service or taking videos. “Guthook Guides has helped make phones more socially acceptable on the trail,” she says.

Sometimes use of the app enters into the absurd. “We came across many hikers who would use the app to the point they would lose common sense,” says Jen Nicholson, a 29-year-old physical therapist who also thru-hiked the Continental Divide Trail last year. She recalls hikers who insisted on walking five feet off to the side of the trail because their GPS told them that’s where the path was.

Then there are the stories of hikers relying on trail apps who lose or break their phone or even just run out of battery. For those who forgo paper backup maps to save weight (I was guilty of this myself), a dead phone makes getting lost more frightening than thrilling. Rachel Brown, membership-services manager for the Continental Divide Trail Coalition, recalls encountering this multiple times when hiking the trail in 2015. A friend of hers lost her phone, spent hours searching for it, didn’t find it, and had no backup maps. “She ended up camping out at a really confusing trail junction for three days until somebody else came,” Brown says. Another time, Brown hiked with a man who dropped his phone into a creek. “He ended up sticking like glue to my partner and me,” she recalls. “It was a little frustrating for us, because it kind of felt like we were babysitting. He was always there.”

Perhaps most telling is Guthook’s own experience. Last summer on a backpacking trip, Linn found he had drifted off of a poorly marked trail. “I stopped, and I was about to grab my phone,” says Linn. “Now I have to really consciously tell myself, No, no no. You just noticed you’re off the trail, go and find it.” Linn is pensive about how his app has affected life on trails. “There are downsides to every new technology in the wilderness,” he admits. “Probably people are using Guthook a little more than I would have wanted.”

“It gave me more self-reliance, which is a big deal with a disability. That almost brings a tear to my eye.”

But Linn has no regrets. The app, after all, has had many positive effects, too. For one, Guthook Guides has worked to conserve the trails it has helped make so easy to hike. Linn has collaborated with trail administrators like Sommerville and the Appalachian Trail Conservancy to find ways to encourage sustainable thru-hiking. Linn and his team have removed unapproved campsites from Guthook Guides at the conservancy’s request, reducing the impact on fragile ecosystems not intended for overnight use. And now when Linn codes a new trail for the app, he reaches out directly to trail associations for data, giving them the ultimate say on campsites designations, water sources, and so on.

The app has also helped make long-distance trails accessible to many people who otherwise might not have the opportunity, like Curt Ebert. The 47-year-old public speaker from Illinois dearly wanted to hike the Appalachian Trail but feared that being legally blind would put him in danger. Unable to accurately distinguish topographical features while hiking, Ebert found traditional maps to be of limited use. With Guthook Guides, he could simply use the GPS to check if he had veered off course. “It gave me peace to know I was on the trail, and it’d give you the direction to go if you did get off the trail,” says Ebert. “It gave me more self-reliance, which is a big deal with a disability. That almost brings a tear to my eye.”

For all the good and the bad attributable to Guthook Guides, the consensus is things are just different now. In 2003, Eric Lee accidentally turned off the PCT and hours later ran into another hiker who told him he was going the wrong way. Lee didn’t believe him. “We brought out paper maps and discussed it for 15 minutes” before the other hiker convinced Lee of the truth. Back then that was part of the experience, and maybe even charm, of the trail. “Today that would never happen,” says Lee. “But I’m OK with that.”