Sarah Marquis Is Breaking Up Exploration’s Boys Club

She walks across entire continents. She has a Spidey sense for alligators and avalanches. And she is redefining what it means to be a modern-day explorer.

New perk: Easily find new routes and hidden gems, upcoming running events, and more near you. Your weekly Local Running Newsletter has everything you need to lace up! .

The map of southwest Tasmania is an unbroken expanse of forest green. There are no towns and no roads on this remote section of Australia’s largest island. There’s nothing save for a few sharply creased mountains and an array of lakes and streams. In many pockets of the rainforest, an endemic tree, the slow-growing horizontal scrub, sprouts a noxious tangle of drooping branches that spawn vertical shoots and crosshatching suckers until the woods are all but impenetrable. In 1822, when the Brits ran penal colonies in Tasmania, a group of escaped convicts ate one another while attempting a getaway through this forest.��

Last year, though, a Swiss explorer, 47-year-old , set out on a three-month, south-to-north solo traverse of Tasmania that included a long push through this thick rainforest. Moving forward at roughly two miles a day, carrying a 75-pound pack in the constant rain, Marquis hacked through the vinelike woody snares with a machete. She clambered at times to the top of the thicket, where she was frequently forced to trample on tree limbs 15 feet��above the forest floor. She could have died stepping on a rotten branch.

But what got her was a steep ravine roughly 500 yards across at its top. On the second day of thrashing her way down through the first side of the ravine’s waterlogged, vine-snared V, the muddy soil gave way beneath her, and she was swept, along with a cascade of rocks and ferns and trees, into a cold river. She blacked out, and when she awoke, she was facedown in the water. Her left arm screamed in pain. Her sat��phone was useless at the shadowed base of the canyon. Was she just going to die down there?��

Marquis had certainly been in tight spots before. She’s a hiking specialist who spends months, sometimes even years, walking across scarcely traveled swaths of earth. From 2010 to 2013, she trekked 10,000 miles from Siberia to the Gobi Desert, then (after 13 days on a cargo ship) across Australia. In 2015, on another visit to Oz, she spent three months subsisting almost entirely on roots and grubs that she caught and fish that she snared. She has camped in minus-30-degree cold��and endured blizzards, sandstorms, mudslides, dengue fever, and an almost fatal tooth infection.��

Marquis is a modern-day explorer—but though anguish and suffering are as part and parcel of��her expeditions as they were to early polar explorers like Robert Peary and Roald Amundsen, her goals are different. A hundred and ten years ago, the objectives of exploration were clear: you pointed yourself at some blank spot on the map and then muscled toward it and planted your flag. Today, however, nearly all terra incognita on the planet is gone. Conquering is a dead art.��

“We’ve moved away from focusing on exploration for exploration’s sake,” says Cheryl Zook, director of the Explorers Program at the National Geographic Society. The��program now funds filmmakers and oceanographers, anthropologists and crime investigators. It also funds Marquis, who’s been a National Geographic Explorer since 2015��and is the author of seven French-language books about her expeditions.��

OK, there are still��a few superstrivers who chase after clearly delineated iconic goals—American Colin O’Brady, for instance, who last year became the first person to cross all 932 miles of the Antarctic��landmass solo, unaided and unsupported, a feat he accomplished in 54 days while pulling a 300-pound sled. Arguably, though, the new soul of exploration lies in less harried and more imaginative quadrants, where a disparate constellation of world wanderers is dreaming up new ways to draw meaningful lines on our thoroughly traveled globe. Think here of Paul Salopek, a Pulitzer Prize–winning journalist now on a multiyear, 21,000-mile global walk that is retracing��the paths of the first human migrants to disperse from Africa in the Stone Age. Salopek’s cross-cultural journey is of a piece��with an earlier feat of new-school exploration, swimmer Lynne Cox’s of the Bering Strait between Alaska and Russia in 1987. In 44-degree waters, in the shadow of the Cold War, Cox was trying to forge détente between the U.S. and the U.S.S.R.

Modern exploration isn’t necessarily steeped in geopolitical themes. It’s about probing new depths on old turf with an inventive flourish and passion. Last June, on Strava, the recently retired Tour de France cyclist Ted King posted a 182-mile, nine-plus-hour Vermont-to-New Hampshire back-roads ramble, captioning it, “I rode to see my dad to wish him a Happy Father’s Day.”

Yes, I thought, pressing the��“kudos”��button within the app. The man’s an explorer.

Sometimes��the new-school explorer travels inward, searching for forgotten zones of the human psyche. Marquis says she travels—and crawls through deserts and rivers and mud—to “rediscover the lost language between humans and the animal kingdom.” She aims, always, for an unmitigated one-on-one communion with nature. She wants to prove that, even amid the abstracted digital fog of our 21st-century lives, a human being can still sit alone by a campfire and feel primitive, like an animal.��

Marquis’s goal is entirely her own invention—she is, if nothing else, a free woman—and in chasing after that goal, she has been catcalled and harassed in most of the earth’s major languages. She has not flinched, perhaps because she’s been too focused on evading the other crazy perils that pervade all great adventure.

Down in the ravine, it turned out, Marquis had snapped the top of her humerus, the big, upper bone in her arm. She considered downing an emergency dose of Tramadol, a painkilling opiate. But she couldn’t afford to numb her senses. There were scores of black snakes in the underbrush, and her sat��phone wouldn’t work down there, amid the thick vegetation. She would need to hike out for three days to find��reception and a clearing big enough for a helicopter landing.��������������������������������

So she did. Off-balance, thanks to her pack and her gimp arm, she fell, over and over. Each crash sent a crescendo of pain into her shoulder. She��met the copter, and then, two weeks later, against doctor’s orders, returned to her hiking route. She had to skip the last section of dense bush, but��she spent three weeks completing a modified, easier version of her intended hike, walking mostly on flat, treeless paths, wincing each time her pack jostled her shoulder.��

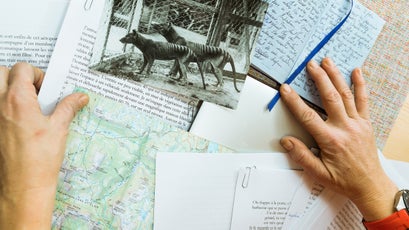

It’s January now, nearly a year after the completion of Marquis’s��Tasmanian expedition, and I’m visiting her in Switzerland, in her tiny, 400-square-foot, seventies-era chalet,��which sits half a mile off the nearest all-season road in the Swiss Alps. It’s cold outside, and she’s wearing a black fleece, black sweatpants, and beige Uggs as she sits on a stool in her kitchen. Her long blond��hair is in disarray. We’re watching snow fall in the sparse forest outside, down onto the boughs of the evergreens. There are houses nearby, but they are snow-caked summer houses, and the world is so quiet that I think I hear the snow falling.

Marquis bought this house, the long-neglected summer abode of a distinguished Geneva family, in 2017. Trash cluttered the home’s warren of mini bedrooms at closing; there was a dessicated crow in the chimney. Still, Marquis envisioned the place a “quiet writer’s cave.” In an e-mail, she told me, “I’ve been waiting all my life for such a place.”��

In the past, she’s tapped out her books in a mountain bungalow in Thailand, on a windblown crag in the Swiss Alps, and deep in the Spanish countryside. Now��she’s pinioned at home, nursing a broken rib, this injury sustained in a prosaic tumble down a snowy Swiss staircase. She’s writing a book about her Tasmanian travels, and taped to a picture window, on Post-it Notes, are hand-scrawled ideas for her first draft. I feel like I’ve stepped into her mind, into her dream. I remember what she wrote to me earlier, discussing the cabin: “I will spend the harsh winter of the Swiss Alps here, with no vehicle access. I’ll move with a canoe in summer and on foot in winter.”

Off-balance, thanks to her pack and her gimp arm, she fell, over and over. Each crash sent a crescendo of pain into her shoulder. She met the copter, and then, two weeks later, against doctor’s orders, returned to her hiking route.

I’ve come here to imbibe Marquis’s idyllic cabin life��and also to meditate on a question that I often ask myself, being a journalist who’s reported stories on six continents: How does a restless person find a still spot in the world? How can a nomad make a home, that is at once sustaining and invigorating, not boring?��

I want Marquis to tell me that she’s going to learn the names of all the plants and birds outside her door. I want her to tell me that she’ll live in this house until she dies, that she’s already 800 pages into writing a book about the place. But now, as she cooks us some organic vegan whole-wheat pasta, she’s backpedaling from her florid e-mail. “This is just a base camp for me,” she says. “That’s all. It’s a place to store my fancy clothes. This is not my type of bush here. I belong to the Australian bush. I know every bird there, every tree, and I’d take a eucalyptus over a pine any day. And no”—she laughs, rolling her eyes before dissing me in her Australian-tinged English—“I don’t think of dying here. I don’t even have a bloody idea what I’m doing next week.”��

Jeezum, did I fly all the way across the Atlantic to get tacks thrown into my path like this? I can already sense a certain tension: I’m a man, here to write about a woman who’s prevailed in life because she’s kicked back against men who sought to write her script.��

On the steppes of Mongolia, drunken nomads on horseback galloped out to��Marquis’s tent night after night and surrounded her, taunting her, just for fun. Marquis, in turn, terrorized two such antagonists after they charged at her with their horses. “I throw myself toward them all at once, arms in the air and screaming like a madwoman,” she writes��in��, the only book of hers that has been translated into English. She’s intent on “scaring them and throwing them off balance,” and she��succeeds. “They glare angrily, understanding that I’m not afraid,” she writes. “They depart without another word.”

During my four-day stay, Marquis will be nothing but gracious, buying me one Swiss chocolate bar after another. But throughout,��her message remains clear: men need to reframe how they think about women in exploration.��

Marquis and I travel��one afternoon��to the nearby village of Chandolin, to visit the onetime home of her childhood idol, legendary 20th-century Swiss explorer and writer Ella Maillart. Maillart competed in the 1924 Olympics��as a sailor��and then went on to lead an all-women’s sailing mission to Crete and travel across the Takla Makan Desert from Beijing to India��with journalist Peter Fleming. Marquis becomes incensed when we discover that the town’s only Maillart museum is a single, unattended room arrayed with a few dusty photographs. “This is bullshit,” she says. “If Ella Maillart was a man, there’d be a brand-new museum here, with videos and sound effects.”

In time��I’ll learn of how Marquis slept in pink leggings every night in the Mongolian desert, just to feel feminine as she towed a bulky cart through the dirt. I’ll discover her Martha Stewart side, when she gives me a copy of her coffee-table book��La Nature Dans Ma Vie (Nature in My Life), which gives readers tips on how they can be just like her, supported by��40 photos of the author—Marquis sitting lotus style, her flowing tresses exquisitely coiffed, her makeup just so; Marquis communing winsomely with a wicker basket of garden-fresh carrots; and so on.��

Sarah Marquis is reframing what an explorer can do and be. So can’t I reframe my own understanding of how her life works?

Maybe I’ll have to, for she has never fit neatly into anyone else’s story line.

Marquis grew up on a farm in Switzerland’s rainy north country, surrounded by ducks and chicken and sheep, in a village so remote that she didn’t see a movie in a theater until she was 15. She and her brother, Joel, who’s two years younger,��named each of the towering beech trees near their home. They climbed into the crowns of the trees, balancing on narrow branches 60 feet up as they swayed in the wind.��

Starting when Marquis was five, her mother took her into the forest to hunt for mushrooms and medicinal plants. “I was learning everything about survival,” says Marquis.��

As a teenager, she left home for a railway job that involved traveling all over Switzerland, managing the operations of trains. Her coworkers, older men mostly, harassed her. (According to a New York Times Magazine , on her first day, one colleague proclaimed that he could smell when she was on her period.) She took such taunts as a challenge. At age 17, alone, she rode a horse across Turkey. Then, in her twenties, she worked as a waitress at a ski resort and ventured, often, on brave expeditions that tested her still meager outdoor skills. She ventured into the��bush of New Zealand’s South Island, for example, endeavoring��to live for a month only on fish that she speared. She lost 15 pounds.��

Eventually, when she was 29, Marquis conceived her first grand expedition—an 8,700-mile loop around the interior of Australia. She was still a waitress; major sponsorship was a pipe dream. But Joel, by then an accomplished engineer and��windsurfer who traveled the world in search of waves, was in her corner—and he was lucky. One day��Joel bought a two-dollar��lottery ticket and found, scratching it, three miniature TV icons in a row. He’d earned a��hard-to-come-by��invite onto a Swiss game show.��

Before a live audience, Joel won $25,000. He used the funds to launch his sister’s expedition. “Nobody thought she could make it,” he explained to me, “but I knew she could. When we climbed those trees, she was steady and strong.” Joel flew to Australia��so he could serve as expedition coordinator, and the siblings collaborated with an ease and a fluidity that at times transcended language. “There wasn’t any need to explain things,” Marquis says. “We were in a desert, without landmarks or trees, and he’d leave a food drop, and I’d know where it was.”��

Marquis’s first book,��L’aventurière Des Sables (The �����ԹϺ���r of the Sands), published in 2004, recounted that Australia trip. She self-published it, at the age of 32. Then she visited every bookstore in French-speaking Switzerland and genially, over coffee, cajoled dozens of store owners to buy the book on her own special terms—money up front, no returns. She spoke at over a hundred schools, accompanied by her dog and her brother, who punctuated her stories by riffing on his didgeridoo. Video snippets of her Australian adventure began showing up on Swiss television.

In 2006, Marquis spent eight��months on a solo hike through the Andes, battling altitude sickness as she made her way to Machu Picchu. In 2010, she began her trek from Siberia to Australia. Gradually, and quite casually, Marquis became a household name in French-speaking Switzerland. A loyal contingent of fans bought every book that she wrote, and her fame seeped into France. The French edition of her 2014��book,��Wild by Nature,��sold 180,000 copies, and in 2018, the French sports magazine������ֱ�ܾ������put her on the cover.��

Marquis is now sponsored by Icebreaker (an underwear brand), the North Face, Sportiva boots, Tissot watches, and Debiopharm, a Swiss pharmaceutical company. But she says she gets no salary. “They just fund an expedition if they like it,” she says of her sponsors. “I have to fight for the money every time. I still work my ass off.”��

Marquis’s publisher, Elsa Lafon, says that the explorer is popular because there’s really nothing transcendent or superhuman about her. “Sarah��has no background as an Olympian, and she’s not an extreme skier or snowboarder,” explains Lafon. “She’s walking, and walking is something everyone can do. It’s also a spiritual activity. People want to live as she does, and when I was with her in Switzerland, everyone stopped her to take pictures.”

Like so many celebrities, Marquis is torn about her status as a public figure. In a way, she loves it. When we’re at a restaurant one afternoon, she begins snapping photos of our food. “You can’t even imagine how many young women follow me on ,” she explains��happily. “There’s a whole new wave of single women out there traveling alone now. They’re not waiting for the perfect partner to do the journey.” Marquis knows she’s their role model. “I’m not attached to some magical guy who’s paying for everything,” she says. “And you’ll never see me doing a photo shoot in a bikini. I could have played that game. I didn’t.”��

But if Marquis loves inspiring young acolytes, she still likes her privacy. We’re sitting in a remote booth at the restaurant, to avoid gawkers, and now she tells me that her highest ideal is “pure exploration. I want to be in nature until I become nature,” she explains, “until it doesn’t matter whether I’m a man or a woman and I arrive at the core of things.”��

When Marquis bought the chalet,��it should have been razed. Starting afresh—building a brand-new cabin—would have been easier than breathing new life into a ruin, but the local Swiss zoning regulations forbid teardowns.��

Marquis turned to her brother for assistance—that was a given. No one in her life (save perhaps��her mother) has been more unwaveringly supportive. When Sarah and I meet Joel one afternoon��at a café, I note that sister and brother share the same tilt to their heads, the same glinting smile. Joel is more settled now. He and his partner have two kids, and he has a lucrative gig as a Swiss Alps tour guide. He’s always up for a challenge, though, so he and Sarah spent a month filling two dumpsters with garbage as they meditated on an architectural challenge: How do you transform a moldy, claustrophobic bunkhouse into a stylish writer’s hermitage?��

Their scheme came together jaggedly, with nothing written on paper. “We came up with a new plan every day,” says Sarah, “and then we changed our minds.”

The process, more intuitive than logical, is of a piece with the strategies Marquis deploys to survive in the wilds. She prepares meticulously, drying and vacuum-sealing all her own food, but out in the field she’s guided quite often by her gut. Once, when she was camping beneath a cliff in China, she had a premonition that there’d be an avalanche. She moved her tent. Ten minutes later, according to Sarah,��the rocks buried her earlier campsite. In Australia in 2015, she says, she evolved a Spidey sense as to which creeks contained crocodiles and which didn’t. (“I became a crocodile,” she says.) She claims to carry an internal compass, so that she can tell which way is north, without even consulting the stars.��

“Women have more of an animal sense,” she says. “We’re made to bear a child. We’re hormonal creatures, and we are able to feel our bodies and the earth. And surviving in the wild isn’t just about strength. You need to have an understanding of the landscape. Women have that, and they can use that to survive.”��

Even though she’s intent on liberating women everywhere, there’s still a bit of the old-world explorer about Sarah Marquis. In the tradition of travel writers such as Paul Theroux and V.S. Naipaul, she is unafraid to be dismissive of the people she meets in the field. Wild by Nature sees her lampooning some of the Mongolians she encounters as “fat” and as “idiots” as she gripes about how they “pee right next to me” and frequent a bar that “smells of musty oldness mixed with vomit.” In fairness, she also reports on the generosity of local women who help her out. In reviewing the book, Publisher’s Weekly complained about her “long diatribes,” saying they “sometimes border on the culturally insensitive.”

When I ask her about that review, she’s not pleased with me. “Americans,” she says, “have no idea of how the world works.��What is that reviewer saying? That it’s OK��for me for me to be attacked every night? So I’m culturally insensitive? I bloody don’t care. That’s your problem!”��

I’m not sure if she means me or the reviewer, and I’m a little afraid to ask. But I guess I’m not shocked that her rough travel experiences have leavened her romantic streak with a sliver of grim, Hobbesian skepticism about human nature. “Look,” she says, still dwelling on her Mongolian attackers, “it’s complicated. On that trip, I learned empathy. I became a better person. But we are all animals at the base. Everyone’s got their own world, and sometimes you are not welcome in that world. I wasn’t welcome there.”��

So she keeps coming home, back to the mountains of Switzerland, where she has now finally built a house of her own, through arduous labor.

In the end, Marquis tore out most of the chalet’s walls and folded the kitchen around a new wood-burning stove��that feeds to the chimney. There are still distinct rooms, but there are no doors on the office or the dining nook, and light pours in through the glass entry door. The white pine decor, meanwhile, is buoyantly bright.

Marquis grew up on a farm in Switzerland’s rainy north country, surrounded by ducks and chicken and sheep, in a village so remote that she didn’t see a movie in a theater until she was 15.

For me, though, what leaps out is that this chalet is shaped to house a single creative person—a second resident would be a stretch. In Wild by Nature, Marquis covers her romantic life glancingly, alluding to “hairy, bare chests where I rested my head for an instant,” and in another book she mentions a breakup that “left me as scarred as if I’d fallen from a five-story building.” At one point��she tells me, “I love everything about men. There is nothing so exciting as a man who knows his strengths, his inner beauty.”��

But she still seems likely to keep inhabiting her tiny home by her lonesome. “I’ve had long relationships,” she tells me, “but always, after some time, the man wants more, and I’m like, More of what?��What they want more of is me, and I will not compromise who I am to be with a man.”��

Marquis gazes out the window, contemplating, then continues. “But I don’t know,” she says. “Love has everything to do with freedom—with deep communication, with allowing your partner to do what they want. But I’ve never met a man who’s understood me completely.” She rises up from her chair now. “Oh!” she says, throwing her arms up in faux exasperation.��“Let’s go for a walk.”��

We step out of the chalet, Marquis coughing a bit each time the frayed edge of her rib tickles her lungs, and we stroll along a cross-country ski trail, chatting about the guises she assumes out on expedition. “I dress like a man,” she says, “for safety, and if I need to talk to somebody, I’m like this.” She drops her shoulders��now, so her arms hang, apelike and foreboding, by her sides as she continues in a low, gravelly voice. “‘Where’s water?’ If they say something,” she continues, “I jump right in. I don’t give them any time to think.” Her voice goes gravelly again. “‘Is it a good stream? How far?’”��

We keep walking. She tells me about the training she does in the six-month lead-up to each expedition. On a typical day, she says, she might run for an hour, then do a three-hour hike to a peak carrying a 65-pound backpack before swimming two or three miles. “By six at night,” she says, “I am dead.”

We pass a lone skier poling along, and then Marquis shares a trick she learned years ago, studying karate. It involves watching one’s opponent closely, waiting for his focus to ebb, and then moving in for a flash strike. To my surprise, she demonstrates, suddenly jabbing her arm toward my chest, so I stagger backward��a step. “It’s useful,” she says of the move.

When we reach the village and come to the garage where she parks her car, she opens the back to load some stuff in, and then, wanting to be of help, I press down on the hatch, trying to close it. The thing does not budge, not at all, so then, instinctively, I just reef on that hatch. I push down on it, hard, until I hear Marquis beside me, shuddering in distress. “Don’t,” she says. “Don’t! It’s hydraulic!”��

“Oh,” I say. “Sorry.”��

As we wind down out of the mountains, switchbacking, gazing at the roofs of the houses below, I apologize again. But then, when we’re in a parking lot with the hatch open, I forget. I find myself muscling down on the damned thing again.

“Bill, Bill, Bill!” Marquis says, copping a feigned scolding tone. She’s laughing, but still I have to wonder why I’m doing this. I’m a spacehead—that’s part of it. But do I also feel the need to demonstrate my strength? I have to admit, I do. I feel intimidated by Marquis. She’s blended her feminine qualities and raw physical strength to become a force on her own terms, an athlete and explorer I’ll never match.��

It’s easy for men to say they champion the end of sexism in the outdoors, but when women start thrashing us��or even marginalizing us? That takes a little recalibration. Speaking plainly, it’s hard on the fragile male ego. It stings sometimes. I’m not condoning the drunken Mongolian nomads or the Swiss dingleberries who threw Ella Maillart’s life history into a closet-size��dustbin, but I do understand their mindset—and also how pathetic it is.����

I’m staying in the village, in a sunlit hillside condo. I can’t tell you the name of the burg (I promised), but there are a few hundred people here��and a post office and a café��in��which the village’s most distinguished female residents gather each morning at 8:30 to chat. The ���ܱ�������������é carries only one small rack of books, all of them by Sarah Marquis, but when fans show up, seeking an audience with the author, the store’s clerks throw them off the scent.��

The realtor across the street from the store��is also protective of Sarah who, before buying the��chalet, lived in the village on and off for years��in a succession of rentals. Françoise is seventy-something, and petit, and inclined to wear black leather trousers��à��la Joan Jett. It is she who sold Sarah her house. “Other people were interested,” she tells me, “but I said, ‘No, it is not for sale.’”��

Françoise, I think, felt a kinship with Sarah. She’s done some exploring herself—in 1980, she flew around the world on the Concorde—and the two women are friends. When I meet with them for coffee one morning, they sit side by side and regard one another with a glimmering affection, reveling, it seems, in the knowledge that they are both free spirits��and fierce.

Still, when I’m invited��one evening��to celebrate Françoise’s birthday at the café, Sarah isn’t there. The fondue party goes on without her. And Françoise, speaking precisely, suggests that the absence carries a certain rightness.

“She is part of the village, and she is not,” Françoise says. “As she wishes.”

“So,” I ask, “where are you going for your next expedition?” Marquis is taking me to the train station. “Antarctica?”

“That’s for the boys. They love to gear up and go fast. They love that physical challenge.” I scribe these words into my notebook��and, watching me as she swoops through the switchbacks, Marquis��becomes irked. “Come on,” she says. “I know��you’re going to use that quote out of context.”��

I change the subject. “OK,” I say. “But what’s, like, your system for determining where you’re going to go?”

Do I really expect there to be an intricate mathematical process? Or that she’ll let me in on the secret? She tells me she looks for signs. Earlier��she showed me a picture of a dragon’s��blood tree on Yemen’s arid Socotra Island. It was at once Seussian and soulful, a giant, mushroom-shaped thing with knotted brown branches and palmlike green needles. “One day,” she says, “I’d like to go there.” When Yemen’s civil war ends, she means.����

We wind pass the church spire in a lower village. “But how long do you think you’ll keep doing expeditions?” I ask.

“I don’t know,” Sarah says sharply. “I don’t think the way you do.” A moment later, she softens. “I’m going to be an awesome old woman,” she says. “My face will be a topo map of all the places I’ve been. I’ll be a little dry apple, but I will never get old.”

When we reach the train station, I remember the hydraulic thing as I retrieve my suitcase from the back of the car. Sarah walks me out onto the platform. Per Swiss tradition, she kisses me three times on the cheeks—right, then left, then right. And then she walks away, and I watch the woman who can go anywhere in the world climb into her car and start back up the switchbacks toward her chalet in the snow.

Editor's Note: The story has been updated to specify that Colin O'Brady crossed the Antarctic��landmass but not the continent's ice shelves.��