Inside the Mind of Thru-Hiking’s Most Devious Con Man

For more than two decades, Jeff Caldwell has lured in hikers, couchsurfers, and other women (and they're almost always women), enthralling them with his tales of adventure. Then he manufactures personal crises and exploits their sympathy to rip them off.

New perk: Easily find new routes and hidden gems, upcoming running events, and more near you. Your weekly Local Running Newsletter has everything you need to lace up! .

On a Thursday in late April, Melissa Trent, a single mother in Colorado Springs, Colorado, logged into her account on the dating website and had a new message from a user called “lovetohike1972.” “I can’t believe a woman as pretty as you is on a site like this,” he wrote.

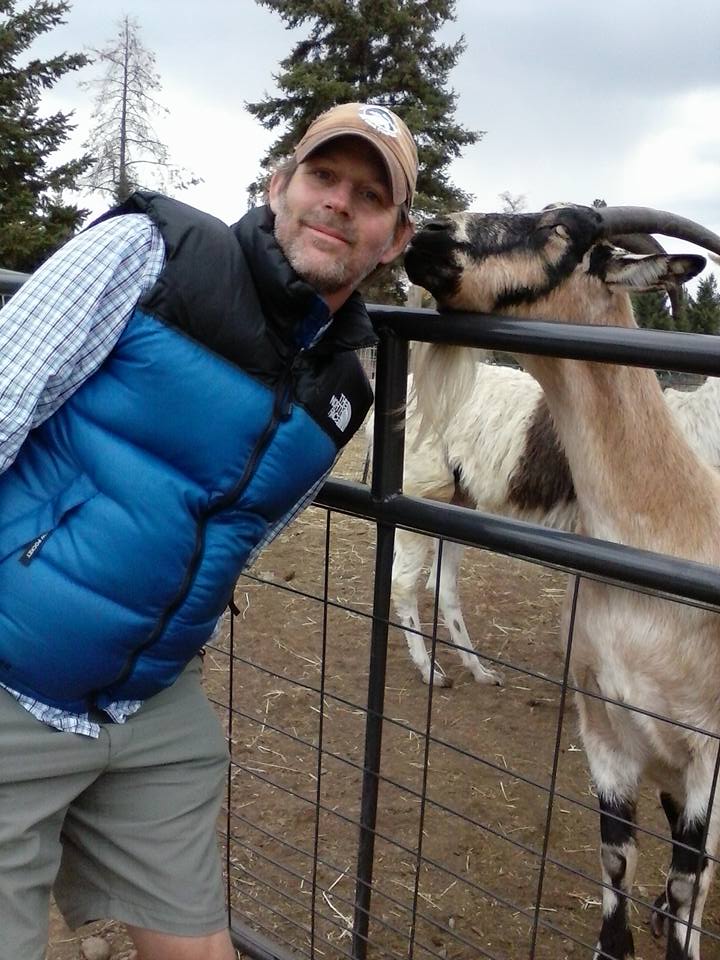

Trent clicked open the man’s account. The photos showed a smiling, clean-shaven guy in a Marmot puffy with chunky glasses and shaggy hair curling up from under a baseball cap. Trent thought he looked cute. There were shots of him atop Pikes Peak, hanging out with thru-hiking buddies at a hostel in Seattle, and climbing into a tractor in Montana. “I love adventure,” he wrote in his profile. “Anything in the outdoors.” His interests included hiking, biking, skiing, craft beer, and the occasional toke.

Trent, who is in her 40s, hadn’t had much luck with online dating, but this guy seemed promising. He was smart and good-looking and she especially liked that he was outdoorsy. After exchanging a few messages, she gave him her number. When he called that evening, he introduced himself as Jeff Cantwell. He said he was born on Kodiak Island, Alaska, and had recently moved to Colorado Springs, where he was training to be an arborist. Most guys Trent had spoken to from dating sites were gross, bringing up sex during a first phone call. “Jeff didn’t do that,” she says. “He wanted to know about my favorite flower.” They ended up talking for ten hours.

Two days later, Trent and Cantwell met for burgers. The connection they made on the phone seemed to deepen in person. They talked about Pikes Peak, which he claimed to have climbed over 200 times, and he also told her how he had lost his parents in a car crash when he was 18. When the bill came, Cantwell paid. A few days later he came over and made spaghetti with meatballs for Trent and her two daughters.

Over the next week, they texted and talked every day. To Trent, it seemed like they grew closer with each conversation. She asked if he had ever been married, and Cantwell revealed more about his history of heartache and loss. During the car accident that killed his parents, his fiancée, and his five-month-old baby were also killed, he said. He enlisted in the army and deployed to Afghanistan, where he was the victim of a severe knife attack. He apparently found some consolation in nature, however. He showed Trent tattoos on his calves that he said he earned for completing hiking’s so-called Triple Crown—the Pacific Crest Trail, the Continental Divide Trail, and the Appalachian Trail.

That weekend, when Cantwell said his bank card had stopped working, Trent lent him a couple hundred dollars. She trusted him. On Monday morning, when she let him borrow her blue Audi A4 to go get a new bank card, she figured he wouldn’t be gone long. About 30 minutes later, however, Cantwell texted that he’d need to go to the branch in Denver, more than an hour away. He asked if he could use the credit card she left in the car to get gas. Trent gave him the go-ahead, but now she was getting nervous. She didn’t remember leaving her card there.

Cantwell’s behavior grew stranger that afternoon. He claimed the bank in Denver had already closed by the time he got there. “I’ll have to sleep in the parking lot,” he told Trent. She knew something wasn’t adding up, but she didn’t want to believe the worst. “I thought we had a connection,” she says.

When Cantwell’s texts became increasingly erratic that night, Trent finally called the El Paso County Sheriff’s Department. They used Cantwell’s cell-phone number to identify him as 44-year-old Jeffrey Dean Caldwell, a Virginia native who’d been locked up in three states for seven felonies, including burglary, writing bad checks, and attempted escape. Most recently, he’d been paroled in September 2016, after serving time in Colorado for identity theft. But in April, shortly before he met Trent, he had stopped reporting to his parole officer.

Still, Trent couldn’t quite convince herself that the man she’d met had such a dark side. “Can I hear your voice one more time?” she begged him in a text. Part of her wanted to trick him into returning the car. Part of her still believed the man she’d fallen so hard for had to exist somewhere. “I don’t want you to go to prison. We have to figure out a way out of this. Can we leave the state?”

Caldwell did call her one last time, but when she started sobbing, he hung up. “I’m sick in the head,” he texted her. “Write to me in prison.”

The cops put out a warrant for Caldwell’s arrest, but he wasn’t known to be violent and no one expected he’d be locked up any time soon. “These con men are transient and move around a lot without any way to track where they are,” says Lieutenant James Disner of the Larimer County Sheriff’s Office, which had arrested Caldwell almost a decade ago. “I have been successful in a few of these types of cases, but only by reaching out to the communities they prey on.”

Caldwell’s victims typically fell into one of two communities: elderly people and women, whom he often found by participating in Facebook and Meetup groups for hikers, by using the website , and by hanging around trailheads, hostels, and outdoor gear stores. By the time he met Trent, he had been traveling across the West, presenting himself as a free-spirited outdoor archetype, for over a decade. On his Couchsurfing account, he used the name John McCandless, the same middle and last name as Christopher McCandless, the charismatic wanderer profiled by Jon Krakauer in .

When we see a man with a trail-worn Gore-Tex jacket and a decade-old Dana Designs backpack, we instinctively trust him. We can’t help but envy his authenticity, his freedom.

A pattern emerged with each of Caldwell’s cons, too. He’d scope out a victim, share his tale of woe, then enthrall her with his adventures (“31 wolves talking to each other!”) and quixotic pursuits (“I’m buying land. 155 acres. You can come stay with me. . . putting up a yurt”). Next, he’d give her a sentimental gift—say, an Alaska shot glass or an Appalachian Trail patch—and send her selfies from the mountains. Finally, he would orchestrate a personal crisis that ranged from the plausible to the bizarre, and finish it off by asking for a small loan or else he’d just steal what was lying around. The con might be over within days. In a few cases, he was able to stretch out such a relationship for years.

At the end of each con, he would apparently be wracked by regret, sending messages to victims that often began with him sounding apologetic and self-pitying, then switching to angry and entitled. “You were a means to an end. Adios,” he wrote one woman. “No crime done, just sniveling broads.” The moment the authorities caught Caldwell, he would confess everything.

As I learned about Caldwell’s exploits, I wondered if there was something about the outdoor community and our sympathy for such wanderers that may make us especially easy marks. When we see a man with a trail-worn Gore-Tex jacket and a decade-old Dana Designs backpack, we instinctively trust him. We can’t help but envy his authenticity, his freedom. He’s not just a weekend warrior—he’s living the life we want. Or at least, that’s how it seems.

For six weeks, I texted Caldwell at a number that Trent had given me, but he never responded. Then, on June 27, he finally sent me a text along with a photo of himself sporting a blue flannel shirt while lounging on a rolled-up fleece in a pine forest. When we spoke on the phone a couple days later, I could hear birds chirping. At first he told me he was in northern Arizona. Later, he claimed he was near the popular Barr Trail on Pikes Peak. “I know Pikes Peak,” he said, “I can hide on this mountain for a long time.”

He agreed to speak with me because he hoped that, by coming clean in public, he wouldn’t be able to take advantage of anyone ever again. “There has got to be a reason why I’m here,” he said. “There’s got to be. It can’t be to keep scamming people.”

Over the next week, we talked for several hours and exchanged hundreds of text messages. “Living like this gets lonely,” he said. He estimated that he’s conned 20 to 25 people over the course of his life, but it doesn’t seem like there are clear lines in his head between a friend, lover, or potential victim. “I don’t go into meeting somebody thinking I’m going to use them,” he said. “It just happens when I’m down and out.” He wasn’t always honest with me, minimizing some of his crimes and the extent to which he manipulated people. Still, he was more transparent than I expected, providing me with access to his email and Facebook accounts. I checked everything he told me with public records and through interviews with dozens of people who had met him.

Caldwell was born in Roanoke, Virginia, on October 26, 1972, the son of a Navy captain and an office worker. His parents split when he was 10 months old, and he and his mother, Susan, moved to southern California. Money was tight and Caldwell says his mother was too busy with boyfriends to give him much attention. (I couldn’t confirm this, as Susan Caldwell died in 2015.) As a teenager, Caldwell says he became a troublemaker. Skipping school, breaking windows, and staying out all night became routine.

When Caldwell was around 16, Susan turned him over to the , a family services organization in Virginia that bounced him between foster families and group homes. He never finished high school and the day he turned 18, he set off on his own.

Caldwell spent his first few weeks of freedom camping out in a creek bed in the woods behind the Hanging Rock Golf Club in Salem, Virginia. But he felt unmoored. In August 1991, he enlisted in the Army Reserve. After 13 weeks of basic training, the Reserves just required him to report to duty for one weekend each month over the next two years. (He’d be honorably discharged after two and a half years.) The rest of the time he was back in Roanoke, sleeping on couches and attaching himself to a group of outdoorsy potheads who were starting college or working day jobs. Caldwell didn’t have his own car, but he had a knack for picking up young girls who could shuttle him around. “I liked him and he was fun to hang out with,” recalls one friend, Heather Riddle.

In June 1993, Caldwell finagled a job as a tennis instructor at Virginia’s oldest girls’ camp, Camp Carysbrook, by presenting himself as a student at . Toward the end of the summer, he snuck into a shed by the lake and stole some camping and rock climbing gear and sent it back to Roanoke with a friend. Then, he says, he hiked a section of the Appalachian trail from McAfee Knob north to the James River. It’s a distance of only 60 miles, but Caldwell spent three weeks out there with friends. “We weren’t pushing for miles,” he says.

When Caldwell returned to Roanoke, he says he started betraying the people closest to him. He snagged a checkbook from one buddy. From another, he stole a camera. The Camp Carysbrook theft caught up to him that winter when a friend’s mother ratted him out and he was handed his first prison sentence—two-and-half years in Tazewell, Virginia.

After Caldwell was released in 1996, he worked odd jobs in the Missouri Ozarks yet failed to pay the restitution he owed. A year later, he got arrested again, this time for writing a bogus $10.16 check to a convenience store from a bank account that didn’t exist. He could have wiped out the resulting three-year sentence with three months in prison under the state’s “shock incarceration” program, which tries to rehabilitate nonviolent offenders. But he violated the terms of his parole three times and got locked up again each time.

In 2004, Caldwell fled from his parole obligations once again and took off to Topeka, Kansas, where he met a woman who was working at the homeless shelter he was staying in. According to Caldwell, they went on a camping trip to Colorado, fell in love with the Rockies, and made plans to move there. But when she became pregnant, he balked at the idea of marriage. Her family convinced them to move back to Kansas to have the child, but his heart wasn’t in it. “Everything started to go downhill after that,” he says. (Through her family, the woman declined to speak about the relationship.)

Whenever I asked Caldwell to explain what motivated him, he seemed unwilling or unable to reflect on his behavior. Maybe he manipulated people simply because he could.

The couple never married and Caldwell drifted in and out of his daughter’s life over the next three years. He failed to pay child support, according to court records. One night, drunk on margaritas, he broke a window, got arrested, and was sent back to Missouri. In May 2004, he forfeited his parental rights.

Not surprisingly, Caldwell’s actual backstory was quite different than the one he shared with Trent and other victims, even if some of the details, like the name Cantwell, had some vague connection to reality. He wasn’t an injured war veteran, but he had been in the Reserves. He hadn’t lost a child in a tragic accident, but he was a father. And his family wasn’t dead. Well, of that he wasn’t sure. But he imagined they were. It was easier that way. “I didn’t want to tell people the real story,” he says.

In the summer of 2006, Paul Twardock was at his office at Alaska Pacific University in Anchorage, where he’s a , when his phone rang. He glanced at the caller ID and was surprised to see that it was from Missouri’s King County Correctional Center.

Jeff Caldwell introduced himself as an incoming student—his high GED scores had made him eligible for a full financial aid package—and he said that he was eager to get some academic advice. “While we were talking, I asked him what he was doing in jail,” Twardock recalled recently. Caldwell admitted that he had passed some bad checks. “He seemed remorseful.”

By the time he arrived in Alaska, Caldwell, then 34, was styling himself as a real adventurer, sporting mountaineering boots when he strutted into Kaladi Brothers, the local coffee chain. Caldwell says he genuinely wanted a fresh start, but couldn’t handle the class schedule. He didn’t even last a semester.

Within weeks, he was stealing from friends and roommates, marking the start of his strategy of flattery and deception. He says he wasn’t motivated so much by the money or adventure. He longed to get close to people—almost exclusively women—to be swaddled, pampered, and mothered by them. “They keep offering to help, so you say ‘OK,’” he says. “It’s so comfortable. I am a nice person, but I have that evil person that’s also there.”

Con men like Caldwell have been known to spend years pretending to be someone else, building a relationship for a financial payoff that is, quite often, dwarfed by the investment in time. Maria Konnikova, psychologist and author of says that the true motivation of the swindler is never money. “They want to have power over other people,” she says. “What is more controlling than the most intimate thing of all?”

Caldwell eventually left Alaska, staying ahead of the law for a while as he hopped across the West. In August 2007, he met Erika, a mountain biker with long blonde hair who had just started graduate school in Montana and needed a friend. (Erika asked that her last name not be used in the story.) “He was kind of a charmer and had these amazing stories,” she says. “I was enamored by the idea of living in the middle-of-nowhere in Alaska.” They hiked to the “M” overlooking town, and Caldwell brought a bottle of red wine that they shared at the top.

Yet over the next month, Caldwell never invited Erika into his place. That seemed odd to her. He tried to brush off her questions about it, but he also got clingy, showing up at her place late at night or meeting her after class with flowers. When she confronted him about his behavior, he said he was working undercover for the DEA and taking her to his house would put them in danger. Caldwell says he didn’t want to tell her that he was really living at the Poverello Center, a homeless shelter downtown. He was in love with her. “I was nervous about telling her the truth,” he says.

A month after they met, she loaned him her truck while she was in class. When she got home, he had stolen her backpack and an enormous jar of change. He left the truck in the parking lot of a nearby grocery store—the keys in the ignition and a “Thank You” note in the cab.

The grifts continued. The next year, Caldwell swiped a credit card and $1,900 in cash from a woman he met at a bar in Fort Collins, Colorado. He took a train to Lynchburg, Virginia, then used the stolen credit card to load up on $800 of camping gear, including a JetBoil stove and a Steripen. The cops learned that he had checked into a motel that night, but by the time they arrived, he had made a dash for the Appalachian Trail.

Caldwell says he spent the next month hiking south more than 500 miles—a breakneck pace which, if you believe him, would require climbing and descending an average of 4,500 feet over 20 miles every day. “I can do 10 by lunch,” Caldwell insists. On October 30, he was coming out of a grocery store in Robbinsville, North Carolina, when a cop ran his ID and arrested him for the theft in Colorado.

Caldwell spent the next six years in and out of prison and halfway houses, but he never dropped his outdoor persona. While he was on parole in July 2015, he headed to in Colorado Springs and had the three thru-trail symbols inked on his calves. Then, thanks to the western chapter of the , he flew to Portland, Oregon. The group had given him their thru-hiker scholarship to attend their annual gathering because he claimed to have just completed the Triple Crown. He told people his trail name was “Mr. Breeze,” but even that was stolen. He had evidently lifted it from another hiker. Caldwell convinced an older couple at the conference to loan him $500, which he never repaid. “Being in the trail community, I couldn’t believe that somebody would do this to another hiker,” says ALDHA-west president Whitney LaRuffa.

Caldwell used the money to buy a train ticket to Whitefish, Montana. He hiked around and answered a Craigslist ad for a live-in caretaker at the All Mosta Ranch, a livestock rescue center run by Kate Borton, a woman in her 60s who goes by “Granny Kate.”

Borton says she knew something was off about Caldwell the moment she let him stay with her. He talked about wanting to hike around Europe and about buying an off-the-grid property, but she doubted he had the wherewithal to accomplish any of it. After a few months, she and her husband asked Caldwell to move on. They later discovered he had used her credit card without permission, but she didn’t resent him. She felt sad. It seemed like he was following someone else’s dream, Borton says, going through the motions of a life that he could never truly live.

“What was missing?” she says. “The heart.”

We all create narratives about ourselves, about who we are, where we come from, and who we want to be. Caldwell told me he lied about the Triple Crown because it was “an accomplishment that people are amazed by,” but it was “a useless lie like most lies I tell.” He said he didn’t necessarily target people in the outdoors community: they just happened to be the people he liked to spend the most time with.

Whenever I asked Caldwell to explain what motivated him, he seemed unwilling or unable to reflect on his behavior. Maybe he manipulated people simply because he could. He told me he became better looking in his 30s, discovering then how much he could get away with. When I said it seemed like he’d given up on a normal life, he scoffed. “Whos EVER going to give me a chance at a decent job, Brendan? No one. I’m a modern day leper,” he texted. I pressed him again a few days later. “U asked why i tell lies? Pretend to be someone else,” he wrote. “Ever heard of self aggrandizement? If not, look it up(:”

Con men like Caldwell have been known to spend years pretending to be someone else, building a relationship for a financial payoff that is, quite often, dwarfed by the investment in time.

In late June, as we corresponded, Caldwell was still driving around in Trent’s car and told me his goal was to make a little honest money before he turned himself in. He asked if I would pay for a motel or help him out in any way, but I said I could only pay for us to talk on the phone. I knew he was starting to see me as another mark, but I still felt guilty about saying no. I saw how easy it was to be charmed by him. He was bright and had a self-deprecating sense of humor. When I broke the news to him that his mother was dead, he told me he was despondent. “Im truly alone,” he texted. He longed for something better for himself, and I wanted to believe that he was ready to turn his life around.

I didn’t hear from Caldwell for a few days. He had assured me he wasn’t leaving the state, but on July 1, he was arrested coming out of a coffee shop in Spearfish, South Dakota, where he’d gone to work a carnival. I reached him a couple days later at the Deadwood Jail. “I’m glad this is over, actually,” he said. As a repeat offender, he was potentially facing 25 years in prison for stealing Melissa Trent’s car and joyriding in it. He was almost looking forward to the prison time. “Maybe, deep down, I’m comfortable in there.” He told me he’d texted Melissa Trent to apologize. “I do feel bad for everything.”

A few weeks later, when he was transferred Washington County Jail in Akron, Colorado, he wrote me several letters. He was on an antidepressant, Wellbutrin, and taking three classes: Time for a Change, Healthy Relationships, and Anger Management. “Being a writer for �����ԹϺ��� magazine must be an exciting job,” he wrote. “I had so much potential. I could’ve possibly been in the cubicle next to you working on my next story.” In the next letter, he sounded optimistic about his case and planned to plead not guilty. “[Melissa] gave me the keys and she got her car back with no damage. We’ll see!”

That’s one way to put it. After all, it was the cops in Spearfish who gave her back the car after he was arrested. Trent says it was a mess. He had blown out the speakers and the engine had to be replaced because he had driven it for so long while it was low on oil. His dirty clothes were in the trunk and there was part of a condom wrapper under the front seat. Trent’s ex-husband helped her clean it up and scrape off all the brewery and gear-company stickers that Caldwell had plastered on the back windshield. As she went through Caldwell’s things, she found a little black notebook of Caldwell’s in the backseat. It contained all of his contacts and even some of his passwords.

On July 26, Trent used the information from the book to access his Facebook account, which had become, in recent years, a living record of the man that Caldwell longed to be. Trent decided to start editing it, to make it reflect, more clearly, the man who he truly was. She took down the profile picture of him as a bearded mountain man and replaced it with a shot of him in an orange prison jumpsuit. “I am a conman,” she wrote under his introduction. “I befriend people posing as a nice, hiking fellow. I steal from them then disappear.”

Then, she added a post about Caldwell’s next adventure. “Going to prison,” it read. “Hopefully, they’ll put me away for a very long time.”

Brendan Borrell () is an �����ԹϺ��� contributing writer. Katherine Lam is an �����ԹϺ��� contributing artist.