You find a dead body lying in the middle of a field in the wilderness. It has no apparent injuries, and its clothes are undisturbed. What happened?

This may sound like a parlor game, but it’s a familiar real-life challenge for forensic pathologists. , doctors from Tunisia report three such cases. In each one, they eventually found marks called Lichtenberg figures, a reddish fern-like branching pattern on the surface of the skin that results from a lightning strike. As a result, despite suspicious-looking bruises and abrasions in one of the cases, they were able to rule out foul play.

The catch? These figures generally appear after about an hour, then fade without a trace within 48 hours, so it’s crucial to identify and photograph them as soon as possible to establish the cause of death. That’s why the Tunisian doctors shared this case series in the journal, in order to raise awareness. And it’s the same motivation for the wide range of unusual injuries and deaths in remote places that Wilderness & Environmental Medicine reports. How can you be ready to treat the victim of a Sri Lankan sloth bear attack if you’ve never even heard of it?

In that forewarned-is-forearmed spirit, here are some of the hazards described in the last few issues of the journal. Tread carefully out there.

Crocodiles

From emergency physicians in Puducherry, India, comes the tale of while washing on the riverbank. At the trauma center, doctors stitched up six different lacerations, cleaned and dressed the wounds, and administered antibiotics. But something still didn’t look right. An ultrasound revealed that the pressure of the crocodile’s jaws had generated enough bruising to completely block the femoral artery and vein, cutting off the leg’s blood supply.

Based on the Mangled Extremity Severity Score (MESS), the patient was predicted to lose his leg. But once they realized why blood flow was cut off, they were able to operate and restore circulation, and he made a full recovery. The takeaway: croc bites can look pretty gruesome on the surface, but their blunt force of up to 2,000 pounds can also wreak havoc internally. Check the ultrasound.

Slugs

On a monsoon-soaked afternoon in rural Nepal, police brought a corpse to the local forensic medical facility for autopsy. It was a 47-year-old male of average build and generally good health (other than being dead). Examination revealed a four-inch-long slug lodged in his trachea, facing upward, which had caused him to asphyxiate. Friends explained that the man was in the habit of swallowing slugs to relieve his arthritic joint pain.

The authors of note that belief in unproven folk remedies continues to thrive in remote locales, in part because of the difficulty of accessing modern medical care. They suggest recruiting more healthcare workers in remote areas, and perhaps offering modern medical training to traditional healers. They also note that eating slugs is a bad idea under any circumstances, citing a 2001 case in Sydney, Australia, where a young man was hospitalized with parasitic meningitis after swallowing two leopard slugs from his garden on a dare.

Mushrooms

Foraging was one of my favorite pandemic hobbies, but one group of potential edibles I steered clear of was mushrooms: it’s just too hard to know which ones are safe unless you’re an expert. Doctors in Atlanta and Turkey a pair of poisonings from Amanita muscaria, better known as fly agaric, and even better known as the spotted mushrooms in Super Mario Brothers and the Smurfs. They’re relatively easy to identify, and widely known to be toxic, though boiling and/or soaking is supposed to remove enough toxins to make them safe to eat. They’re also psychoactive.

The U.S. poisoning involved a 44-year-old who ingested six to ten dried fly agarics that his friend bought from a website called IamShaman.com. He passed out half an hour later, and his heart stopped beating after about ten hours. He was rushed to hospital but never regained consciousness. The Turkish victim, a 75-year-old who’d foraged the mushroom for dinner, survived after a long hospital stay. Bottom line: the North American Mycological Association will likely want to update that, in humans, “there are no reliably documented cases of death from the toxins in these mushrooms in the past 100 years.”

Ramps

Sticking with the foraging theme, three people ended up in hospital after eating tacos that included ramps harvested from their backyard. Ramps, sometimes known as wild leeks, are a pungent, garlicky delicacy across eastern North America. Unfortunately, it’s hard to differentiate them from lookalikes such as lily-of-the-valley and false hellebore. Half an hour after the tacos, all three people noticed a strange sensation in their throats, and two of them began vomiting.

At the hospital, they all tested positive for digoxin, a substance found in foxglove plants that is used as a medication for certain heart conditions but can be dangerous in excess. The story gets confusing from there: subsequent testing of plants from the backyard didn’t match up with the symptoms and test results observed in the patients, but it’s not clear whether they managed to find the same plants that they’d eaten. All the patients ended up being OK (there’s an antidote to digoxin overdose), but it’s another reminder to forage with extreme care.

Cliffs

During , one of the high-altitude porters unclipped from his fixed rope and wandered away. He had been showing signs of confusion, and he ignored the calls of his expedition mates to come back. From a ridge on Lhotse face, at about 24,000 feet above sea level, he plunged more than 1,300 feet to the bottom of the face. We know how this story ends: in the medical literature, according to the authors of the report, survivable falls seem to max out around 300 feet.

This particular story has a mostly happy—and unprecedented—ending, though. Climbers from other expeditions rushed to where the porter had landed, and sledded him to an improvised helicopter landing near Camp 2. They called for rescue 15 minutes after he fell; he arrived at Everest Base Camp’s ER at 45 minutes; at Lukla, the main airport into the Everest region, at 75 minutes; and at a hospital in Kathmandu at 150 minutes. He had a skull fracture and swelling in the brain, but was otherwise in surprisingly good shape. He ended up losing sight in his left eye and having some mild cognitive impairment, but was able to return to physical work—though not to climbing.

Crevasses

On June 4, 2017, a party of climbers was . Two of the climbers were unroped, and a few hundred meters from camp one of them plunged through a snow bridge into a crevasse. He fell about 65 feet, and got wedged, still vertically upright, between the narrowing ice walls, which were about eight inches apart.

Subsequent attempts to rescue him were pretty crazy: at one point, a ranger who was lowered down to reach him also got wedged so tightly that he couldn’t breathe, and the other rescuers on top couldn’t hear his cries for help. They tried a chain saw, a blow torch, antifreeze, boiling water, and hacking away at the ice with adzes. After 12.5 hours, a helicopter delivered a pneumatic hammer-chisel. They finally managed to dislodge him 16 hours after he fell. He’d been unresponsive for more than three hours and was presumed dead. But he lived.

The authors of the paper discuss various lessons from this episode, ranging from the obvious (don’t climb unroped) to the nuances of how to transition a hypothermia victim from vertical to horizontal without triggering cardiac arrest. The biggest lesson of all: don’t give up on rescue efforts, because you never know when someone is going to blow away the odds by surviving way longer than expected.

Bugs in Your Ear

I always thought “a bug in your ear” was just an idiom, or a story kids tell to scare each other at summer camp. Then, while backpacking through the fjordlands of Newfoundland last summer, a black fly got stuck in my ear for a few hours. The intermittent buzzing from deep within my skull was maddening and a little scary, and attempts to remove it were painful and (my physician wife warned me) dangerous.

Turns out it’s not that rare, according to . In fact, Asiatic garden beetles crawled into the ears of 186 sleeping campers at a Boy Scouts jamboree in Valley Forge, Pennsylvania, in July 1957. More generally, about half of bugs removed from ears in hospital emergency departments are cockroaches. When adults have something stuck in their ear, it’s an insect about 80 percent of the time; for kids, the percentage is lower “due to children’s proclivity to intentionally place objects in the external auditory canal.”

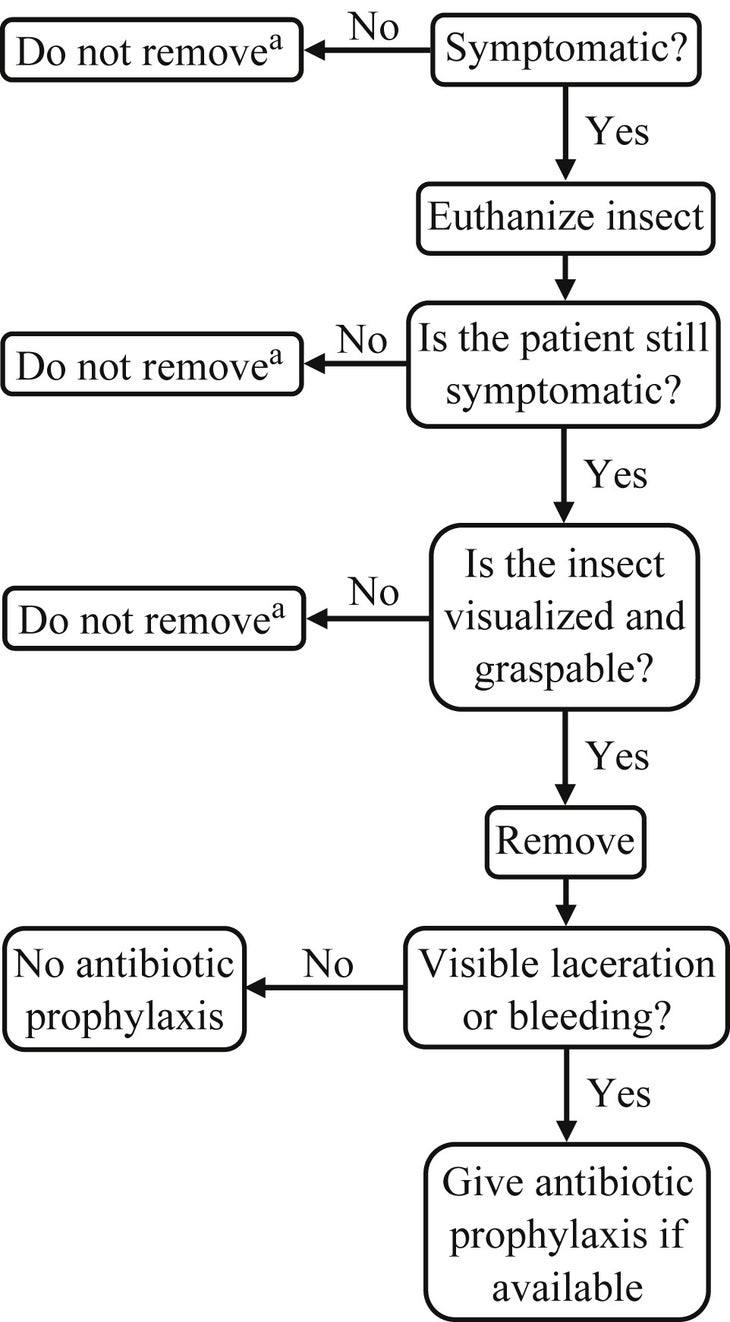

Dealing with bugs in the ear is more challenging in the backcountry, because you don’t usually have specialized equipment with you and there’s a significant danger of damaging the delicate structures of the ear. With that in mind, here’s the decision tree they provide for bug removal in the wilderness:

To sum up: start by killing the bug; don’t go into your ear unless the bug is still bothering you even after you’ve killed it, and you can clearly see it. There are several ways to kill it. The most backcountry-friendly is drowning it in vegetable oil or soapy water. Hopefully your first-aid kit has tweezers, because some of the alternatives—like superglue on a cotton swab—have the potential to go seriously wrong.

A Stick in the Eye

a comprehensive survey all patients who presented at Helsinki University Eye Hospital over a one-year period in 2011-2012 with eye trauma caused by wooden items such as sticks and branches. There were a total of 67 cases, 24 of which occurred in males between the ages of 51 and 67. The accidents mostly took place while playing, gardening, or working in the forest. The takeaways here are pretty straightforward: consider eye protection for forestry and woodworking, and children should be careful while playing with sticks—though, notably, none of the playing-with-sticks injuries resulted in permanent disability.

Sri Lankan Sloth Bears

If you’re out in the Sri Lankan jungle gathering honey or collecting the fruits of the ironwood or dragon’s eye trees, make lots of noise and look out for sloth bears. They’re relatively small, maxing out at around three feet tall at the shoulders, but despite the name they’re faster than humans—and they like those foods too. Most of the ten attacks took place while the victims were alone gathering food. All survived, but that could be because those who don’t survive sloth bear attacks don’t bother coming to the hospital.

There’s no shortage of other dangerous wildlife encounters described in the pages of Wilderness & Environmental Medicine: , , , , , and so on. Sometimes a little extra caution might protect you; other times there’s nothing you can do other than be prepared. If you spend a lot of time in the backcountry, take a , pack a comprehensive first-aid kit, and leave the slugs and mushrooms alone.

For more Sweat Science, join me on and , sign up for the , and check out my book .