Before Henry Worsley, There Was B├╕rge Ousland

David GrannтАЩs New Yorker story about a doomed Antarctic adventurer was a spellbinding read. But as heтАФand ╣·▓·│╘╣╧║┌┴╧тАФseem to forget, other people had already done what Worsley was trying to pull off.

New perk: Easily find new routes and hidden gems, upcoming running events, and more near you. Your weekly Local Running Newsletter has everything you need to lace up! .

Sixty-two days into a planned thousand-mile journey across Antarctica, Henry Worsley, 55, a retired British Army officer, is near exhaustion. ItтАЩs January 2016 and heтАЩs trying to complete that Sir Ernest Shackleton didnтАЩt get to a century earlier. ItтАЩs been tough going.

тАЬEach time he exhaled the moisture froze on his face,тАЭ David Grann. тАЬA chandelier of crystals hung from his beard; his eyebrows were encased like preserved specimens; his eyelashes cracked when he blinked.тАЭ Because Worsley had climbed to 10,000 feet above sea level, where the thin air is brutally cold (nearly minus 40 degrees Fahrenheit), capillaries in his nose have burst and тАЬa crimson mist colored the snow along his path.тАЭ With each step he takes on a pair of cross-country skis, he might accidentally punch through a crust of snow and тАЬvanish into a hidden chasm.тАЭ

Grann is the author of the terrific┬аThe Lost City of Z and the terrific and appalling Killers of the Flower Moon, which is about the systematic murder of land-owning Osage Indians in the 1920s. He could not have typed up WorsleyтАЩs ordeal more vividly if heтАЩd been there. But of course he wasnтАЩt. Worsley is alone. And that turns out to be a crucial point of the story.

Reading Grann, youтАЩd barely know that anyone who isnтАЩt a British subject, or who isnтАЩt from the Golden Age of polar exploration, matters much when it comes to the history of expeditions on Antarctica.

Worsley is traveling тАЬunsupported,тАЭ which is to say without any outside help or resupply caches along the way, and without anyone else on hand to cheer him up, provide first aid, or check his dangerous ambition. (He did, however, have a satellite phone that he eventually used to call in a rescue planeтАФa form of support that Shackleton definitely lacked.) HeтАЩs taking a challenge that is already incredibly hard and making it that much harder in order to see how heтАЩll fare. (Spoiler alert: not well. This effort will cost him his life.) тАЬHe had to haul all his provisions on a sled,тАЭ Grann explains, тАЬwithout the assistance of dogs or a sail. Nobody had attempted this feat before.тАЭ

Those italics are mine, because if you blinked youтАЩd miss a thin-slice qualifier that keeps the next sentence technically true but has some polar veterans wondering if Grann and The New YorkerтАЩs fact-checkers are in the tank for the Crown. Reading Grann, youтАЩd barely know that anyone who isnтАЩt a British subject, or who isnтАЩt from the Golden Age of polar exploration, matters much when it comes to the history of expeditions on Antarctica. And by sticking to WorselyтАЩs justification of his historic тАЬfirstтАЭтАФas ╣·▓·│╘╣╧║┌┴╧┬аhas also done repeatedlyтАФGrann plays into the British knack for romanticizing their polar tragedies at the expense of the far more clever, and undeniably more successful, Scandinavian exploits at the ends of the Earth.

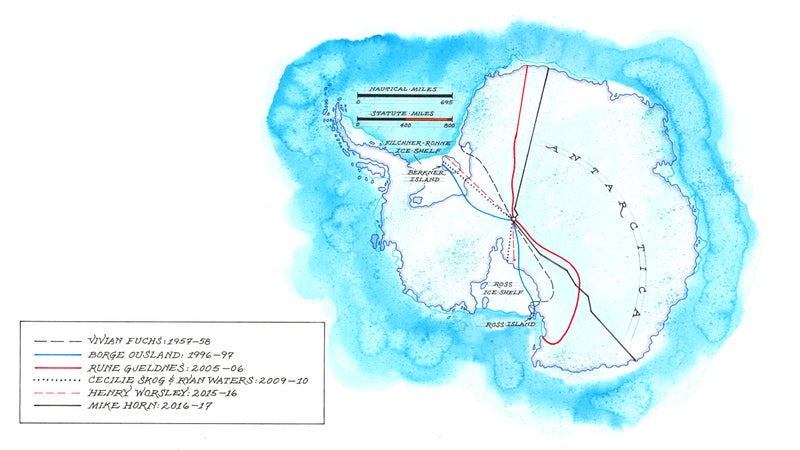

In an article of 20,000-plus words, thereтАЩs plenty of room for WorsleyтАЩs hero, Shackleton, but none for several modern explorers who Worsley consulted for advice, foremost among them B├╕rge Ousland, a Norwegian hardman who became the first person to ski alone across Antarctica in 1996-97. For all practical purposes, two other soloists also have done what Worsley failed to do: OuslandтАЩs countrymen Rune Gjeldnes, who pulled off an astonishing solo traverse in 2005-06, and the Swiss-South African Mike Horn, who did it last year. All three of them skied and used small sails during portions of their tripтАФOusland estimates that a sail helped rip him along for about a third of the distance. (Imagine a kite-surfing rig, only youтАЩre on skis and towing a capsule-like sled.)

While weтАЩre at it, another pair worthy of note is Cecile Skog, a Norwegian woman, and Ryan Waters, an American, who crossed Antarctica together in 2009-10. Like Worsley, they man-hauledтАФthat is, dragged everything they needed in a sledтАФand they didnтАЩt use sails. DonтАЩt they count?

тАЬItтАЩs just ridiculous to say that Worsley would have been the first,тАЭ says Douglas Stoup, the founder of Ice Axe Expeditions, a polar outfitter that has led many trips to both poles. тАЬItтАЩs like thereтАЩs a loophole that allows these British guys to say no oneтАЩs done it, when it has been done.тАЭ Roald Amundsen, who led the first party to the South Pole in December of 1911, , used dogs┬аto get there. тАЬSo was he not first?тАЭ Stoup asks.

Stoup says he met and liked Henry Worsley. Super-nice guy. But he believes that Worsley and others, like , another Brit with an Antarctic obsession, have used subtle qualifiers to assert that something has тАЬnever been doneтАЭ or is a тАЬfirstтАЭ because doing so helps attract sponsors and drives publicity. ThatтАЩs how this game is played. But Stoup finds such casually misleading claims unfair to the real polar trailblazers.

In November of 1996, Ousland set out from the coast of Berkner Island for the second time in an effort to cross Antarctica solo without any help. (HeтАЩd aborted the same mission the year before because of frostbite.) He didnтАЩt warm up inside the South Pole science station when he passed by, for fear of getting тАЬtoo cozy.тАЭ On the leg from the South Pole to the Ross Sea, he opted for a longer, but safer, route through the Axel Heiberg glacier. In all, he completed 1,768┬аmiles. When he arrived at McMurdo Station, on the Ross Sea, heтАЩd been alone on the ice for 64 days and had survived temperatures as low as minus 62┬аFahrenheit. Remarkably, he still had all his fingers and toes and his nose. To Stoup, Ousland set a new standard for self-reliance and тАЬhad done some of the richest living you could do.тАЭ

For the first Trans-Antarctic crossing, completed in 1957-58, British explorer Vivian Fuchs had 11 other┬аmen along and relied on Sno-Cats and dog teams.

So in what way was WorsleyтАЩs mission unprecedented? Well, unlike Ousland, he refused assistance by sail. And according to rules concocted several years later by an adventure-tracking online site called , use of a sail means that OuslandтАЩs trip was тАЬsupportedтАЭтАФby windтАФwhereas Worsley could claim in a mission statement to be тАЬsolo …┬аunsupported, and unassisted.тАЭ

Launched in 1999, ExplorerтАЩs Web filled a niche that the Royal Geographic Society and the National Geographic Society have not bothered with, trying to vet and record the increasingly specialized firsts on peaks and at the poles now that all the major geographic discoveries have been done.

Created by Tom and Tina Sjogren, a Swedish-American couple whoтАЩve been to both poles, the site has often stirred controversy, with many wondering who these self-appointed gatekeepers think they are. тАЬWhy the hell do they make the rules?тАЭ asks Stoup. тАЬAnd what if youтАЩre tired and a stiff wind stands you up? Is that support? What about GPS? What about a tent? Are they supports, too?тАЭ

No, says Tom Sjogren, and neither are snowshoes or a pair of skis. Reached in the Mojave Desert, where he and his wife are now busy building their own space rocket for two, Tom defended their choice of declaring wind to be an expeditionary aid. He drew an analogy to ocean travel, where a sailboat is тАЬsail-supportedтАЭ but a rowboat is human-powered. Though Tom agreed that ski-sails are difficult to master and dangerous in their own rightтАФHorn broke his shoulder after being slammed to the ice by hisтАФhe believes┬аtheyтАЩre game-changers. With a stiff tailwind, they can increase the potential distance you can cover in a day by a factor of five, or even ten.

A sensible person might say that being able to travel farther in a dayтАФin minus-40 degree temperaturesтАФis a smart idea, as are comrades. For the first Trans-Antarctic crossing, completed in 1957-58, British explorer Vivian Fuchs had 11 other┬аmen along and relied on Sno-Cats and dog teams.

But we get the idea: ExplorerтАЩs Web celebrates and respects extremes. To set the bar for future Antarctic efforts, they should probably define тАЬunsupportedтАЭ even more starkly. No sails, no Sno-Cats, no horses, no oxen, and especially no dogs could be used. (Nixing dogs is easy. TheyтАЩre no longer allowed on Antarctica; all non-endemic species except humans are forbidden now.) To cross Antarctica in pure style, youтАЩd have to man-haul a sled with all your rations, no food caches or drops. Only boots or snowshoes would be permittedтАФnothing that eases the physical challenge of completing your journey. (Skis do make travel easier: skiing requires much less effort than postholing.) ItтАЩs OK to have a tent, of course, but no GPS, no iPod, and no┬аsatellite phone like Worsley carried. (Modern communications tools provide too much physical and mental aid. You might as well bring an emotional support penguin.) Once you leave, youтАЩre off the radar until you show up at the other end.┬аOh, and youтАЩll have to pick a new route that isnтАЩt merely the shortest distance you can possibly trace to cross the continent.

Which leads to another sticking point about WorsleyтАЩs plan. Before he left for his fatal 2015-16 expedition, he spoke with Ousland, who says the discussions were тАЬalways in a friendly tone.тАЭ But they had to agree to disagree about some things, including the route Worsley proposed. Ousland completed a traverse that was truly coast-to-coast and, as such, more than 600 miles longer than what Worsley set out to do. Worsley and other Brits, Ousland says, favor тАЬthe short version.тАЭ

тАЬThey end the trip where the mountain meets the shelf ice, called the Filchner-Ronne Ice Shelf on the Weddell side, and the Ross Ice shelf on the Ross side,тАЭ Ousland says. тАЬThese huge ice shelves are 600 to 800 meters thick, and theyтАЩve been there for more than 100,000 years, long before countries like Denmark and the Netherlands existed.тАЭ In OuslandтАЩs view, the ice shelves are part of the continent. If you donтАЩt cross them, you havenтАЩt crossed Antarctica.

тАЬThese U.K. guys are saying theirs will be a first because they do it a bit different, but that is stretching it,тАЭ says Ousland, now 55. Speaking from his home in Oslo, he searches for an American term of art. тАЬItтАЩs a bit of fake truth,тАЭ he says.

In a 2015 interview for National Geographic, the climber and author Mark Synnott asked Worsley about OuslandтАЩs 1997 precedent. тАЬWhat he did was amazing,тАЭ Worsley replied. тАЬAnd IтАЩm not worthy to clean his shoes, but he did use a kite. Maybe itтАЩs a British thing not to use kites. [Robert Falcon] Scott might have well frowned on the use of kites [as he did on the use of dogs], yet Amundsen would use as many dogs as he could, I expect, and not care what anyone said.тАЭ

Dogs! Kites! All of this might seem absurd, and it is. But thereтАЩs more to it than just hair-splitting.

While Scott might have frowned on the тАЬsupportтАЭ of dogs and kites, in 1911┬аhe brought tractors and ponies to Antarctica to help him in his race against Amundsen and his crew to the South Pole. Both forms of travel failed miserably, but Scott would have used them if theyтАЩd worked. His man-hauling expeditionтАФcall it Plan CтАФwas a disaster, ending in the death of him and four other men. And yet when Amundsen beat Scott, he found his methodsтАФwhich included eating exhausted sled dogsтАФdisparaged. It was as if, by paying careful attention to the Inuit, and learning how to travel efficiently in polar regions from native people who knew how to do it right, the Norwegians had somehow cheated.

For his part, Grann obviously meant no disrespect to any unnamed polar explorers. тАЬI was really interested in HenryтАЩs story, and his worship of Shackleton, so it felt more important to know more about Shackleton,тАЭ he told me. тАЬI was interested most in the tension between a devoted family man and his need to push to the limits of endurance.” Also, Grann┬аsaid, adding more context about contemporary explorers would have added words to the article, тАЬand itтАЩs pretty long as it is.тАЭ

Worsley, Grann writes, would often ask himself тАЬWhat would Shacks do?тАЭ Shackleton is veneratedтАФjustly soтАФfor rescuing his men when things went sideways during his 1914┬аexpedition aboard╠¤╖б▓╘╗х│▄░ї▓╣▓╘│ж▒Ё. But what Shacks didnтАЩt do was claim a single polar prize. In seeking to emulate him, Worsley appears to have learned at least one wrong lesson: to make the trip harder than it needed to be. With a sail, Worsley might have made it and lived to tell his story to Grann in person.