Dear Dad,

Scott Carpenter and the Mercury Project

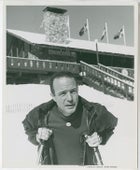

Scott Carpenter and the Mercury Project Scott Carpenter at Vail in 1964

Scott Carpenter at Vail in 1964Thank you for the camera, the books, and skis you sent me, which are all right in front of me. I am reading Mysterious Island first. I hope you read it, for it is very interesting. And all the books I am sure will be interesting. …

The S’s on my report card stand for superb, superior, superhuman, and splendid—at least that’s what I think. But the teacher meant them for satisfactory, the highest grade you can get.

—Scott Carpenter, January 1, 1937

ON SATURDAY, November 2, my father—Project Mercury astronaut —will be mourned and remembered at Saint John’s Episcopal, his boyhood church in Boulder, Colorado. In the spring, when the snow clears, we’ll take his ashes to the Frye place, near Clark, Colorado. Homesteaded in 1901 by his great-uncle John, it hosts family camping trips when not under snow. The grave site will be consecrated among the aspens, near the headgate, and we’ll inter his remains at 8,300 feet, laying him to rest close to the ashes of his infant son, Timothy, dead 60 years now.

This is what my father wanted, to be buried in a place that had shaped him.

Navy test pilot, undersea explorer, and world traveler, my dad was a Mercury astronaut, celebrated in The Right Stuff alongside Alan Shepard, John Glenn, Gus Grissom, Gordon Cooper, Deke Slayton, and Wally Schirra. But before that, he was just a freckled kid in 1930s Boulder, fatherless and slightly feral, besotted with frontier tales, wood lore, scouting, hunting, horseback riding, and adventure literature written for Victorian boys.

Scott was raised by his mother, Florence, and her parents, Vic and Clara Noxon. Boulder-born in 1925, he lived his first two years in New York City, because his father had won a postdoctoral grant to study physical chemistry at Columbia University. But after Florence contracted tuberculosis in 1927, Scott senior returned to his in-laws’ Boulder home, ill wife and two-year-old son in tow. Then he left for New York, promising to return. “Get better,” I think, was the plan. But Florence didn’t get better until 1938, and she supervised her son’s upbringing for ten years, with help from her parents, from her bed. Father and son negotiated their relationship after that through faithful family correspondence and some awkward visits.

Scott gained a few things from the upheaval. In Boulder there was a big house, the outdoors to explore, and loving adults to care for him. The absent, adored, hard-to-please father was his childhood motif—perplexing, normal, and satisfying by turns. Separation brought a mostly safe distance from the man’s caustic appraisals. It also brought an unusual benediction: Scott was raised by a kind grandfather, walking encyclopedia, companion, and sage.

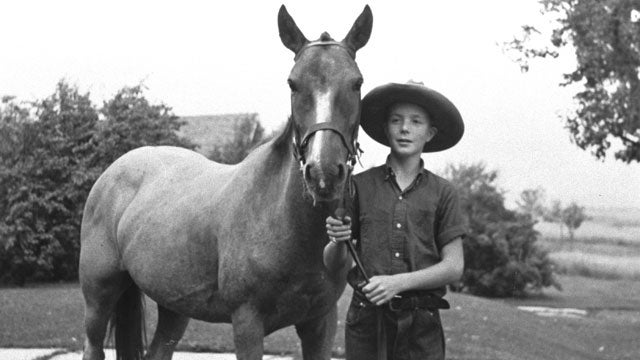

Above all, Scott had the freedom to roam a sparsely populated Front Range landscape. Going by the nickname Buddy, he tramped through the forests behind the family house at Aurora Avenue and Seventh Street, climbed all the Flatirons, and spent half his time in spring, summer, and fall galloping around on Lady Luck, a three-quarters Arabian mare he rode bareback because he knew that’s the way the Sioux rode. In his solitude and freedom of movement, Dad experienced a kind of loneliness that combined with a longing for adventure and, ultimately, a hunger for fame. I see him in those years in a trance induced by fresh air at altitude, racing, dreaming, riding, and reading—most supervision happily avoided.

Scott was a child with evident intellectual gifts. But he was also a musician, glee-club member, and athlete, with obscure interests in what to others seemed outlandish hobbies: bow hunting, hiking, camping. He developed a fascination for edge tools. He could see things that others couldn’t, both as a matter of perspective (he was a near orphan in a town of two-parent children) and fact: he possessed twenty-ten vision.

Once, in an impromptu game of hide-and-seek on Seventh Avenue, Scott found the best hiding place, and his schoolmates gave up finding him and decided to hide from him. He discovered them in short order, and he said it was so funny, their indignation. They chanted, inexplicably, “Your father’s a scientist! Your father’s a scientist!” The taunt mystified him. Years later, after his wartime stint in the V-12 Navy College Training Program, he would return to finish his schooling at the University of Colorado in Boulder, where his dad had gotten his Ph.D. 20 years before. He plugged away at the college courses required of an aspiring engineer, but flying was the thing for him, and he hated his course in heat transfer. Flunked it twice, he remembered. CU conferred it in 1962, conceding that his valuable work experience in heat transfer on May 24, 1962—when he became the fourth American to go to space—fulfilled all the course requirements at the university. He accepted his diploma in a ceremony at Folsom Stadium.

The reward of this obscure boy’s life rests partly on chance: fate kissed his longing for greatness. He mourned the lost age of exploration, and yet all the while he was preparing to play a major role in the next one. The Boy Scout motto is “Be Prepared.” Scott was prepared. Would he have found the same place in history had he grown up in New York? I have trouble imagining it.

��

SCOTT’S MOST BELOVED sport and pastime was skiing—“the closest thing to flying,” he liked to say. The speed, exhilaration, ease of maneuvering, and expanse of sky filled him with an elation that, as an adult, he would often express on chairlifts by letting out a magnificent yodel.

He skied as a young boy with an elite group of Boulder adventurers who were older than him, mostly in their teens and early twenties. Working together, the group solved an important engineering problem, much like the one later posed by spaceflight: How do you get up there? NASA engineers had to figure out how to launch a man into space and bring him safely back to earth. For the group of Boulder visionaries, operating in the era before lift-served ski resorts were common, the problem was nearly as grand: How do you get up the mountain with your skis?

In 1936, at age 11, my dad got his first pair, wooden Northlands with no metal edges, a Christmas gift from his father that came only after years of pleading. Soon he found his way into the Boulder group, headed by a young man named Kirkendahl who had a pretty wife named Libby. With four or five others in the mix, the little ski club built a lodge at a place called the Idaho mine, an old claim perched at 10,000 feet in the mountains west of Boulder. An abandoned miner’s cabin still stood at the site, and after a substantial amount of work over two summers, the group converted it into a warm, weathertight place to live during a multi-day ski trip.

The cabin wasn’t much: one room with four big wooden bunks stacked two high, each wide enough for three people. The bunks had canvas curtains and wooden sideboards that held rough straw mattresses for everyone to put their bedrolls on. A huge old wood-burning stove with a water well and a big oven filled the southwest corner. The stove became “everyone’s best friend,” Dad would later recall.

In 1934, two years before Scott joined in, the group bought a 1928 Chevy sedan and figured out how to cannibalize it and make a lift. In the summer, they drove the Chevy to the abandoned town of Caribou, up past the Idaho mine, and then a few miles farther west over the ridge, down across the valley, past the peat bogs, and beyond the cabin to the flat top of a mine dump. There they removed the wheels and body and anchored the engine and chassis to the ground. Attached to the rear axle was a large spool of cable, and the cable was run to a huge pulley that was anchored to another mine dump way up on the mountain. The cable was run back down the mountain and attached to the body of the Chevy, now mounted on skids.

With that, all they had to do was fire up the engine, put it in gear, and let out the clutch, and four skiers could be hauled up, comfortably seated on upholstered car seats. Depending on who was at the throttle, it was often more fun to ride up than ski down. I assume this was doubly true when Scott was driving.

��

FAST-FORWARD 26 years. As John Glenn’s backup and friend, Scott Carpenter, by then a 37-year-old naval aviator and Mercury astronaut, had been training alongside the relentless Marine for nearly a year in preparation for the United States’ inaugural orbital spaceflight in 1962. On the morning of February 20, Carpenter was in the blockhouse by the launchpad with Convair engineer T. J. O’Malley as Glenn got ready to become the first American to orbit the Earth. Many people remember Carpenter’s send-off, “Godspeed, John Glenn,” which he uttered as the Atlas rocket began to thunder and lift off. O’Malley added, “May the good Lord ride all the way.”

Telemetered readouts during the flight of Friendship 7 showed that Glenn, a fit and healthy Marine, had been pushed to the limits of human endurance by his three-orbit flight. An Air Force cardiologist named Lawrence E. Lamb was alarmed, therefore, when he learned that Deke Slayton was slated for the next Mercury mission. Lamb had examined Slayton in September 1959, at NASA’s request, confirming in a written report to the young space agency that he suffered from an atrial fibrillation. This would not prevent the Air Force pilot from leading an active life, Dr. Lamb wrote, but the condition was medically disqualifying not only for spaceflight, but also for the prime pilot slot in any high-performance aircraft.

The report was initially quashed by NASA—the official word was that Slayton had only “a heart hiccup, nothing more”—but he was eventually deemed unfit for space. And so it happened that, on March 15, 1962, NASA administrator Bob Gilruth announced that my father, John Glenn’s MA-6 alternate, would take the next mission, MA-7.

Slayton’s demotion, and my father’s elevation, stunned the close-knit astronaut corps. However much desired, an outright shunning was difficult to manage at Langley AFB, where NASA was then headquartered. Service wives in general, and Project Mercury wives in particular, were averse to the practice. Keeping his mind on the mission, meanwhile, Carpenter plunged back into the grueling regimen known only to spaceflight pioneers. He had seven weeks.

Carpenter was on the launchpad at Cape Canaveral on the morning of May 24, 1962, atop the Atlas 107-D. Like Glenn, he would be pushed to his physical limits, losing eight pounds of pure sweat during the course of his nearly five-hour flight. His job was straightforward. He was to replicate, and thus confirm, Glenn’s successful orbital mission while working through a different flight plan. As ordered, he would undertake more radical spacecraft maneuvers and perform additional science and engineering experiments. During a successful, largely uneventful flight, intermittently malfunctioning hydrogen-peroxide thrusters, working off false pitch-horizon-scanner readings, wasted fuel during the first two orbits. Carpenter had enough fuel for reentry, and he kept a close eye on the gauges, working through his flight plan methodically.

At retrofire, with his pitch-horizon scanner again malfunctioning, Carpenter did what any astronaut would do. He lined up the scribe line in his small cabin window with the horizon—correcting for pitch attitude—and manually piloted Aurora 7 to a safe landing in the Atlantic. He also had to fire his retro-rockets manually on a count from Al Shepard. They malfunctioned as well, firing two seconds late.

Imagine steering a small, man-made meteor back from space through the atmosphere. It’s called blunt-end reentry, and that’s what the early astronauts did: they rode meteors down to ocean landings. While Carpenter was on his way back, chunks of heat shield started coming off, glowing hotly through his window, and he deployed his drogue chutes early, at 10,000 feet. You do that to keep a meteor from tumbling. It’s the blunt end, with its precious heat shield, that you want beneath you, not the nose. His drogue chutes reefed nicely and stabilized the capsule. He landed safely; no surprise there. He had been training for this moment, he would tell you, since fourth grade.

Once in the ocean, Carpenter secured the cabin, then grabbed his camera and climbed out through the nose of his capsule—a notable feat of upper-body strength never replicated by anyone who followed him in spaceflight. (The usual practice was to stay inside the capsule until a chopper picked the whole thing up.) Perched atop his heat-blistered spacecraft, bobbing in the swells, he inflated his life raft, tethering it to the capsule, and dropped it in the ocean. Clambering down the side, he pulled himself into the raft and lay back for the wait. Patrol planes, he knew, would be looking for him. He had landed more than 250 miles past his splashdown target, a record he would keep until Russian cosmonauts recently outdid him.

For years after, Deke Slayton’s partisans at NASA, flight director Chris Kraft in particular, used Carpenter’s overshot, in vicious rounds of infighting, to bring this consummate astronaut down and others into line. My dad would retire from the astronaut corps in 1967 with a medically grounding injury of his own, sustained in a 1964 motorbike accident. He never flew much after that.

��

and a warm, attentive father. He wasn’t perfect. After the Carpenter family’s ties with NASA dissolved, it seems that our ties to each other dissolved as well. Service to country, and mission, was our only glue. My parents divorced in 1971, after 23 years of marriage and five children—three still living. For many years, I didn’t see my father much after that, and I often wondered why. We would become reacquainted later on, and collaborate for five years on his biography, and my father would explain to me in his inimitably patient way, as we worked through the flight transcript, the mysteries of yaw, pitch, and roll and the challenges of piloting a tiny spacecraft, which were nothing to him. Just something he had been training for since fourth grade.

Thank you, Father, for your gifts of time and attention when I was little. Thank you for your service to country. I missed you when you left.

��

KRIS STOEVER IS THE COAUTHOR OF SCOTT CARPENTER’S 2003 BIOGRAPHY, SHE LIVES IN DENVER WITH HER HUSBAND, TOM.