The Weird, Wild Business of Shrunken Heads

A guy calls, says he found some mysterious papers left behind by a dead relative who apparently shrunk human heads and bodies. Do we wanna come see? Uh, no. But we knew Mary Roach would.

New perk: Easily find new routes and hidden gems, upcoming running events, and more near you. Your weekly Local Running Newsletter has everything you need to lace up! .

Late on afternoon in the Ecuadoran Amazon, a short but imposing Achuar tribeswoman walked up to me with a knife in her hand. The Achuar are the tribe next door to the Shuar, who are known for their historical tradition of shrinking the heads of slain enemies. (Both tribes were formerly, and politically incorrectly, known as the Jívaro, which comes from the Spanish ��í��������, meaning “savage.”) The Achuar had, at the time I visited in 1998, the world’s second-highest murder rate. I was there with an anthropologist named John Patton, who studies intratribal murder and revenge, and the Conambo River Valley was a fruitful place for him to be. Achuar men do not so much as go out for a piss without bringing a rifle.

The woman spoke loudly in words I couldn’t understand. With her free hand, she grabbed my hair. “She wants to make paintbrushes,” Patton said. My hair is finer than Achuar hair, and the woman saw its potential for achieving precise lines and decorative embellishments on the clay bowls she crafted. I went back to the States minus a crudely lopped hank of hair and with a new story that grew with each telling. The knife, which might have been a pair of scissors—I honestly don’t recall—became a machete. The machete acquired bloodstains. The potter took on a stony glower that I claimed to have interpreted as: This scrawny woman in the bulbous shoes annoys me, and I will take her head.

It was a preposterous story. The Achuar were not head shrinkers—as adversaries of the Shuar, they were the shrinkees—and I knew this. I was the latest in a long line of white folk who’ve visited Jívaro country and come home with embroidered tales of scary encounters.

American’s fascination with “savages” and shrunken heads began in the early 1900s, with the publication of the first English-language Jívaro ethnographies and the arrival of the first tsantsas, as ceremonial heads are known, in U.S. museums. The fascination flourished throughout the first half of the 20th century. In the thirties and forties, self-styled “explorers” like and made a living off travelogues depicting life in deepest, darkest you-name-it. �����ԹϺ��� travel as a recreational pursuit did not yet exist. If a man went deep enough into the bush, no one could check his facts.

MY FOUR YEARS WITH THE HEAD HUNTERS OF THE AMAZON, announces the cover of a circa-1940 brochure detailing a lecture that a man named would give, for a fee, at your local Shriners club or ladies’ auxiliary. The pamphlet describes him as the sole survivor of an “illfated botanical expedition.” Struve, it says, was taken captive by headhunters, married the chief’s daughter, and learned “the secret process of shrinking human heads and even entire bodies.”

Shrunken bodies? Struve appeared to have proof; a photo showed a shrunken man nestled in his palm like a passenger in a bucket seat.

Longtime readers of �����ԹϺ��� might recognize Struve’s name from a 1994 article called “Little Men,” by natural-history writer Caroline Alexander. Having learned about two shrunken men on display at New York City’s Museum of the American Indian (MAI), Alexander set out to determine their origins. Museum records provided little beyond this: a doctor from Ecuador, Gustav Struve, had sold them to the museum in the early 1920s. Eventually, Alexander located Struve’s son, now deceased but then living in Quito, who told her interpreter, “Papa used to make the mummies.” No explanation or motive was offered. The director of an archaeological museum in Guayaquil, Ecuador, told Alexander that he’d heard of medical students around that time shrinking unclaimed bodies “as a joke.” The trail ended there, leaving the reader with an image of Struve as an enigmatic grotesquerie.

One person who saw the story was Struve’s grand-nephew David Brown, the manager of a natural-foods co-op in Boise, Idaho. During an expedition to his parents’ Idaho basement in 2003, Brown stumbled upon a box of the old man’s papers. Gustav’s wife, Gertrude, was the sister of Brown’s grandfather. Gustav and Gertrude had no children, so the elderly couple’s belongings wound up with Gertrude’s brother and eventually made their way to the Browns’ basement.

A few years ago, Brown contacted �����ԹϺ��� to clarify some minor points in the original article. He mentioned the box he’d found and offered to make it available (a generous offer, given that Brown is at work on a book about all this). Even better: Brown was headed to the Chicago-based to examine a “shrunken boy” that Gustav had donated in 1935. This one was a new specimen, distinct from Alexander’s mystery men and the one pictured in Struve’s lecture brochure. And, best of all, it could be viewed in person. Both Alexander and Brown had been denied permission to look at the MAI bodies. (They were removed from public display in the late seventies. Modern political correctness, along with the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, have turned heads and other human remains into ethical hot potatoes.)

It was a rare opportunity to examine a shrunken body and what would appear to be the uniquely twisted mind of Gustav Struve. The story Alexander began could now be told in full.

There’s a reason hunters’ trophies tend to end at the neck. A head is more practical than a body. It’s easier to transport, it’s less time-consuming to prepare, and it confers the same bragging rights. Today, I count 29 heads—most taxidermied, some shrunken—on display in the �����ԹϺ���rs Club’s spacious old headquarters in downtown Chicago. Plus four attached to torsos: mine, David Brown’s, club honcho Howard Rosen’s, and that of Struve’s shrunken boy.

We’re having lunch around the club’s Long Table, a pair of rectangular surfaces pushed end to end and running the length of the main room. The walls and ceiling beams are hung with fringed expedition flags commemorating the adventures that are the primary requirement for membership here. To qualify, an adventure must include “the element of risk to life or limb.” During the club’s heyday in the first half of the 20th century, this often took the form of big-game safari hunting. These days, the definition has been relaxed somewhat. Rosen, a CPA in nearby Riverwoods, earned his flag by fishing for peacock bass in Colombia’s Orinoco River Basin. The peacock bass is not dangerous, but Rosen says he was “almost killed by a gang of 12- and 13-year-old thieves” outside the Bogotá Hotel Intercontinental.

Brown is here to do research. He has taken two years off from his job to devote himself to “Investigating the Life of Dr. Gustavo Struve” (as stated on his current business card). He is 57 but looks younger, the gray in his beard just starting to get the upper hand on the red. He wears a chunky sweater-vest and a tweed blazer with leather elbow patches. Brown’s attire and soft-spoken manner give him a professorial stiffness at odds with the bully-bully, wisecracking camaraderie of the club regulars who drift in and out during lunch hour.

The Shuar believed that killing a man created an avenging soul that would leave the corpse via the mouth and come after the perpetrator.

Like a cop or an undertaker, Brown has grown blasé about the grisly particulars of his current work. He refers to head shrinking as a “kind of craft.” As in, “It wouldn’t bother me to have my head shrunk. If I found someone who did this kind of craft.”

“Teach me!” Rosen says in his gleeful, booming bass. “If you go before me, I’ll do you!”

Lunch plates are cleared. A staffer has unlocked a glass-fronted display cabinet and is wordlessly removing bell jars that hold the museum’s collection of shrunken heads, placing them in front of Brown and me. It’s like some cheesy horror movie where the guest is treated with the utmost decorum until he lifts a plate cover and finds he’s been served the head of his beloved.

“Here comes the boy,” Brown says.

Thirteen inches from heel to crown, the specimen is mounted on a mahogany stand that could serve as a paper-towel holder. The first thing you notice is the skin color. The Shuar believed that killing a man created an avenging soul that would leave the corpse via the mouth and come after the perpetrator. Lips were sewn shut to prevent this, and true ceremonial tsantsas have blackened skin, the result of the killer having rubbed it with charcoal to prevent the victim’s spirit from “seeing” out. This child’s skin is the buff color and rough texture of a dried kalamata fig. Based on its proportions—the plump bowed legs, the nubbin of a penis, the fat cheeks—it looks more like a mummified infant than a shrunken boy. In fact, the inventory lists it as “stillborn.”

“Gustav told us it had been given to him by the Shuar and that he carried it out when he escaped,” Brown says. “He never told us that he himself shrunk humans.”

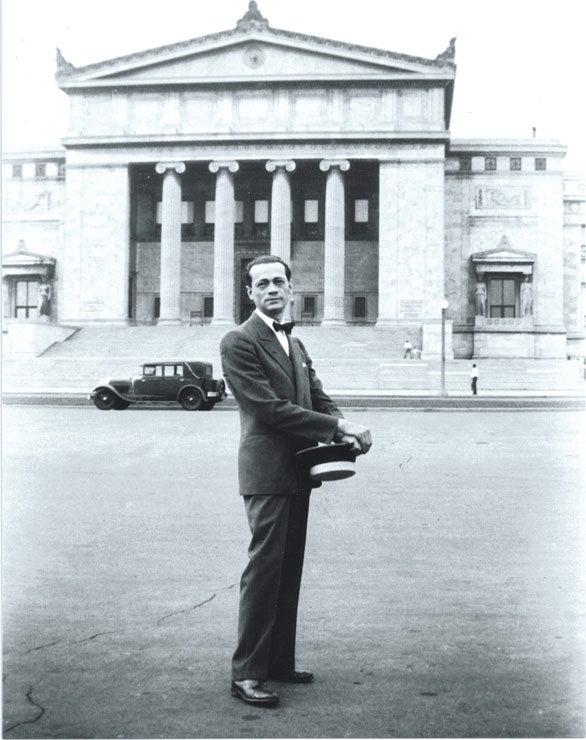

Brown has his laptop open and has been clicking through images from his family’s photo albums. He shows me a 1955 shot of Gus and Gert—as American friends sometimes called them—seated at a restaurant table for a family dinner in Los Angeles. Bowls and spoons are set before them. Struve looks at the camera with the mild peevishness of an old guy who wants to have his soup. He wears dress suspenders over a short-sleeved button-down shirt and sports the pencil-thin mustache he wore most of his adult life. I remark to Brown that it’s hard to picture this natty gentleman flaying bodies and boiling skins.

“Check the pattern on the shirt,” he says. I lean in closer. The shirt is decorated with a row of tsantsas, life-size and garish, with lips sewn shut and flowing Wonder Woman hair.

“So he was a bit of an odd one,” I say.

“I would stand there and visualize the stories my great-uncle Gustav told me about killing monkeys and slitting their throats and tossing them in the river to distract the fish so they could cross,” he said.

“Well, bear in mind,” Brown says quickly, “America was in the midst of a shrunken-head craze.” He calls up a 1960s TV ad for a toy Witch Dr. Head Shrinkers Kit (“Shrunken heads for all occasions!”) featuring a pith-helmeted actor hacking his way through what looks like a Kansas wheat field.

Brown seems a little conflicted. On one hand, he hopes to launch a writing career by conveying the lurid escapades of his great-uncle. On the other, he seems protective of a beloved family member’s reputation. Earlier today when we met for coffee, he told me how, as a child, he would visit a mall near his parents’ house that featured a tank of piranhas. “I would stand there and visualize the stories my great-uncle Gustav told me about killing monkeys and slitting their throats and tossing them in the river to distract the fish so they could cross,” he said. This was immediately followed by: “He was a warm guy, loved kids.” The most memorable of Gustav’s stories, of course, involved jungle savages who shrank their enemies’ heads and bodies.

It’s the bodies that, for me, raise a red flag. None of the Jívaro ethnographies mention a anything below the neck. Members of a Shuar war party would strike and retreat swiftly, sticking around just long enough to hack the heads off the fallen and string them on strips of bark or tie them to their headbands. Then they’d flee the scene, heads bobbing against their backsides. To drag off a whole body—even a boy’s—would slow a warrior down and put him at risk of retaliation.

So where did this ghastly object come from? Did Struve make it, as Caroline Alexander suspected? Why? Who shrinks a child?

Gustav Struve was born in Ecuador in 1893 to parents of German descent. He earned a surgical diploma from a university in Guayaquil in 1918, a year after marrying an Ecuadoran woman, with whom he had one son. His résumé lists a span of six years spent traveling around South and Central America in an unspecified “commercial capacity.” He settled for periods in Lima, Panama, the Amazon, and his prolonged absences from his wife devolved into a permanent separation. He traveled to the United States in 1925, settling in Chicago, where he worked for the Argentine consulate. In 1939, he married Gertrude.

Brown has been unable to find any record of the 1914 botanical expedition mentioned in Struve’s lecture brochure. The drafts of a memoir Struve was writing contain no names of fellow party members. “It’s incredibly vague,” Brown says. Did Struve simply make the whole thing up?

“Maybe,” says Brown. “But look at this.” On his laptop, he pulls up a scan of a newspaper clipping he found among Struve’s papers. It details a talk given by a German engineer named Herbert Huth, who claimed to have been taken prisoner by cannibals near the headwaters of the Amazon in the 1920s. Forced to watch his companion tied to a tree and then burned alive (while “Indians danced and sang around the flames”), Huth claimed, he lost consciousness. When he came to, he found himself married to a Jívaro woman, just as Struve had described in his lecture brochure.

And then the clincher. “He claimed to have learned various secrets of the Amazonian Indians, among others a method of reducing the size of human heads and of bodies,” the story says. Brown suspects this story was Struve’s “inspiration”—that he swiped its details to fit his props and then set himself up on the travelogue circuit.

So it appears that there were at least two body shrinkers at work. Likely far more.

As for the props, several facts suggest that Struve fashioned them himself. Brown recalls coyote and fox heads that Struve said he’d shrunk. (It’s not that difficult. See “Do Ick Yourself.”) In a letter to Gertrude dated 1939, he describes visiting a San Francisco museum with a shrunken-heads display. “One of the small heads, of a woman,” he writes, “it has been done by me.” In his 1923 book , explorer Fritz W. Up de Graff mentions a man in Panama who “makes a business of preparing and shrinking heads, and who has even shrunken two entire bodies, one of an adult, the other evidently a child.” By one account, Struve lived in Panama in 1923. Perhaps he did some shrinking there. Or perhaps he just did his head shopping there.

Whether or not Struve made all the specimens himself, he was clearly, as Brown puts it, “a purveyor.” Brown shows me a letter from June 1937, a reply from the director of the Fleishhacker Zoo, in San Francisco, whom Struve had contacted for advice on where to sell “Jívaro shrunken head trophies.” Struve sold one to the �����ԹϺ���rs Club in 1933 for $52.50—about $860 in today’s dollars. And one of the two shrunken men purchased by the MAI fetched $500, a big sum in 1923. Struve’s grandson told Brown that he recalls his grandmother talking about her husband’s trips into Jívaro country to provide medical care. He added, in an e-mail that Brown had translated, that she would not have approved of trafficking in cabezas reducidas—shrunken heads.

And thus, perhaps Struve omitted that part of the story in his communications with family. It is, admittedly, a bit awkward to explain.

One reason Brown has traveled to the �����ԹϺ���rs Club is to inspect the craftwork on the shrunken boy. He wants to compare it with that of the shrunken men Struve sold to the MAI—which in 1989 was absorbed by the congressionally established (NMAI)—to see if they all look like the work of the same hand. The two MAI specimens appear to have been stitched, not glued. Brown learned this from an NMAI anthropologist via an e-mail description; following its standard policy, the museum would not permit him to see the bodies or have them photographed.

Now, handling the boy in Chicago, he turns the body over to inspect the seams on its back. They look glued with some sort of crude sealant, not sewn. So it appears that there were at least two body shrinkers at work.

Likely far more. A spin through the various Jívaro ethnographies reveals that counterfeit human shrinking was a thriving cottage industry. “The majority of heads which leave the country … were never in the hands of the Jívaros but were prepared by various individuals from the bodies of unclaimed paupers to supply the constant demand of tourists and travelers,” ethnographer M. W. Stirling wrote in a 1938 volume of the bulletin of the Bureau of American Ethnology.

Given that shrunken bodies are not true indigenous remains, why shouldn’t the NMAI let Brown photograph them? Basically, because remains of any sort are politically volatile. The NMAI would very much like the little men to go away, but repatriation is tricky because the bodies are not definitively known to be Jívaro.

“You kind of don’t know what to do with them,” Mary Jane Lenz, an archivist with the department, explained when I spoke with her by phone. For now, the pair reside in a storage facility whose location I’ve promised not to reveal.

M. W. Stirling contended that counterfeit tsantsas were made at various places in Ecuador, Colombia, and Panama as far back as 1872, when “a white man living on the borders of the Jívaro country” apparently learned the craft from the natives. The time frame—late 1800s to early 1900s—corresponds with the equally gruesome and lucrative trade in freshly buried corpses dug up by body snatchers and sold to anatomy schools in England and the U.S.

Patton told me that the Shuar, around that time, would refer to the Achuar as fish—as in, “Let’s go catch some fish.”

If you know what to look for, it’s usually a simple matter to detect a counterfeit tsantsa. The fakes often have facial hair; the Shuar took care to singe it off. The lips of counterfeit tsantsas are closed with unwoven strips of vine rather than string, and they lack the holes in the head that would enable a warrior to hang it around his neck during ceremonies.

It wasn’t just tourists and collectors who fell for the ruse. Major institutions, including the American Museum of Natural History and the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History, own a mix of Jívaro-made tsantsas and knockoffs. Of 125 museum-held and privately collected heads examined and photographed by James L. Castner, author of a 2002 book called , only 23 turned out to be authentic.

It’s possible these curators knew they were acquiring fakes and didn’t care. Shrunken heads were a tremendous draw, bodies more so. “They were the stars of the third floor,” Lenz said of the MAI’s pair, which went on display with great fanfare when the museum opened in 1922. She recalls when they were taken off exhibit in the 1970s. “We’d get people who had childhood memories of having seen these figures, and now they were coming back with their children and their grandchildren. They were just crushed that they weren’t there anymore.”

Here’s what surprised me most: the Shuar themselves were prolific commercial head shrinkers. Beginning in the mid-1940s, word spread throughout the region that a tsantsa could be traded for a shotgun. Around the same time, anthropologist John Patton told me, the Shuar gained a tactical advantage over the Achuar. The Achuar had long controlled the rivers, affording access to trade routes and opportunities to barter for superior firearms being made in Brazil and traded up through Peru and Ecuador. Because Shuar headhunters faced retaliation from the better-armed Achuar, head-taking raids were sporadic and carefully considered. And then the balance shifted. A critical section of border closed, cutting off the Achuar’s access to trade and ammunition. The Shuar got busy.

“A hundred and fifty Shuar warriors would go and take heads, whole families,” says Patton, “partly because they had a commercial outlet for it and also because when the Achuar were reduced to using spears it was a lot easier to do.” Patton told me that the Shuar, around that time, would refer to the Achuar as fish—as in, “Let’s go catch some fish.”

It’s impossible to know how many Achuar were killed as a consequence of the market demand for shrunken heads among curators, tourists, and collectors. It’s safe to say that a lot of what passed for adventure in the Amazon back then was little more than ugly commerce. Brown has a 1933 newspaper clipping about an adventurer named Frederick Mitchell-Hedges, interviewed in his hotel room in Chicago with 17 shrunken heads laid out on the bed. Looked at in this light, Struve was just another guy who figured out a way to spin a living from, as Brown put it, “his good looks and shrunken goods.”

Inside the �����ԹϺ���rs Club, Brown closes his laptop. The boy is returned to his place in the display cabinet, near a General Tojo suicide photo and a deck of cards that Roald Amundsen carried to both poles.

“All these guys traveling around with suitcases full of shrunken heads and bodies, filling the public’s collective mind with images of crazed savages,” he says, summing up. “Meanwhile, the folks down south are cranking out heads, picking up the slack when the Jívaro failed to keep up with the demand. And the ‘professionals’ at museums would put them on display as genuine artifacts and enjoy the extra sales at the ticket booth. What a trip.”