For 25��years, an oceanographic buoy�� has been moored in the middle of the Bering Sea��collecting data on ocean conditions��for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. In 2017, it��picked up something extraordinary: the siren song of North Pacific right whales, an endangered species so rare that scientists say tracking one down is like finding a needle in a haystack.

Nearly��2,000��miles away, in Seattle, an environmental educator and boat captain named Kevin Campion was also searching for��signs of the whale. Campion, a 42-year-old West Coast skater turned biologist, was a few years into a about the whales��and nearly a decade into an obsession with them. After a failed attempt to spot them during the summer of 2017, and spurred by Peggy’s findings, Campion blocked off two weeks of the summer of 2019, borrowed a friend’s boat, and roped in two crew members. In August 2019, the team crisscrossed��a��200-nautical-mile stretch of Bering Sea that is the whales’ critical habitat, running the boat’s hydrophone in hopes of hearing what Peggy had.

We know surprisingly little about the species the Center for Biological Diversity calls . We know they can live at least 70 years, and that they get huge—up to 100 tons��and 65 feet long. Thanks to , we think they migrate from California to the Bering Sea, and that there are two surviving populations: one of about 300 whales on the western side of their migration range, and one of about 30 whales on the eastern side, which Campion is tracking.��

We know they still exist because there were two sightings off the coast of British Columbia in 2013, more than 60 years after the last sighting in the area,��and because the acoustic recorder on Peggy captured their song in 2017. That same year,��NOAA recorded several other sightings, including one of a young whale—a hopeful sign that the whales were still reproducing.

North Pacific right whales are members of the baleen whale family, a close relative to the slightly less rare—but much more studied— and whales, which have become a larger part of the conversation about marine-mammal conservation. (They’re all related to the , whose population is endangered but increasing). The recording captured on Peggy��recently that the North Pacific right was a distinct species, because the others don’t sing.

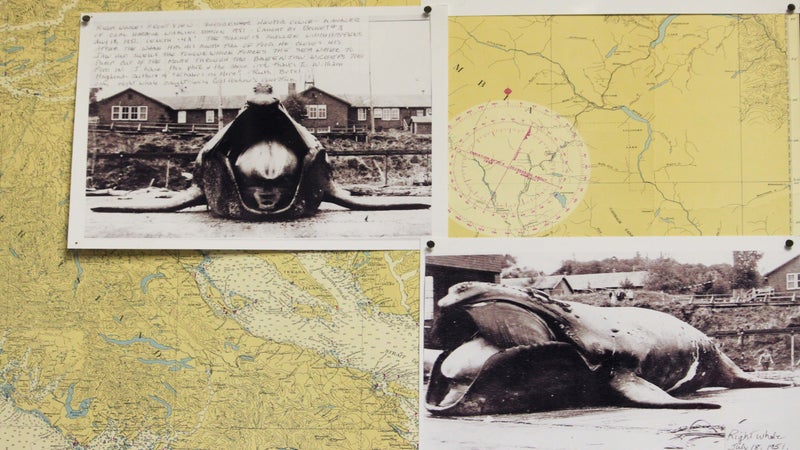

Before whaling took off in the region in the 1830s,��there were an estimated 30,000 North Pacific right whales. Those numbers were quickly decimated: the species is fatter and floatier��than other whales, which made them prime targets for whalers looking for oily blubber. Like most whales, they have long life spans and reproduce slowly; that��hinders population regrowth,��though��it has been illegal to hunt them since 1937. By 1951, when one was documented as having been��killed illegally at a whaling station in Coal Harbor, British Columbia, the North Pacific rights had all but vanished. It has been listed as an endangered species since 1970.

So it seemed to Campion that scientists should have a better handle on these whales. How—in the age of and ��and Google Maps��and Peggy—can the life of an enormous rare creature remain a mystery? How can something so big just disappear?

Campion is a biologist who has sailed vast swaths of the world’s oceans��and runs a marine-science program called Deep Green Wilderness in Seattle. He’s been obsessed with whales since he was a kid, but he had never heard of the species before 2013, when the second North Pacific right to be seen in 60 years was spotted near Vancouver Island. He started reading up and asking the whale researchers he knew about them. Soon��the mystery of the North Pacific rights had pulled him in, in part because their disappearance from human view and scientific study struck him as near mythical.��“The deeper I dug, the less people knew about them,” he says.��

For two summers, Campion has led a crew on trips to search for the whales. The first time, in 2017, Campion’s crew spent about six weeks circling Vancouver Island, where that single North Pacific right had been spotted four years earlier.��He tracked down Brian Gisborne, the 60-year-old former commercial fisherman who had seen the whale in 2013. (Gisborne used to run a water-taxi business��and is contracted by the Canadian Department of Fisheries and Oceans to look for rare species. “He’s spent years of his life at sea,” Campion says. “If anyone had the rights to find something rare, it was this guy.”) Gisborne was initially reticent, but once he warmed up, he shared a wealth of information about where the whales might want to eat��and what topographical features might give them trouble. “We were pretty sure we weren’t going to see one,” Campion says.��“But the researchers were like, ‘You might!’”��

Their first trip was fruitless, whale-wise. But “might” was enough for Campion and his crew to try again in 2019 in the Bering Sea, motivated in part by the��groundbreaking recording captured on the Peggy buoy. By then��the whales had become a focal point of Campion’s lifelong environmentalism: he wanted people to care about the fragile state of the oceans as passionately as he did, and the North Pacific rights were an enigmatic and especially endangered victim of them. By that point, he and his crew had been working on making a film��about the whales since 2017. A sighting, he believed, would help highlight the charismatic megafauna. After all, it’s hard for people to care about things they don’t know about.

When Campion’s crew began��the��second whale expedition, he couldn’t help but get his hopes up. As they headed north, during what was��an unusually warm summer, he felt like they might have a chance. They had diligently researched the most likely place to catch up to the whales��and the time of year that they had the best chance of spotting them. Campion talked to , the scientist who had identified the song of the North Pacific right that was recorded on Peggy. He dove into all the data and reports he could find��and tracked the history of places the whales had been seen. They planned their trip based on whale��behavior as much as possible.

They traveled to the Bering Sea during a year of very low sea ice. If sea-ice concentration is high, then the abundance and concentration of baleen whales’��prey is also high—meaning a buffet for the whales. However, when there is minimal sea ice, there’s a decrease in prey abundance and concentration (which adds another stress variable for the whales, who are already routinely threatened by ships, fishing nets, and ocean noise). They crisscrossed the sea in the heat, recording their journey for their upcoming , which��will reveal the details of the trip, Campion says. He hopes to complete the film later this year.

During these expeditions, and as a result of his research��and his conversations with the few other obsessive people who have tried to track the whale, Campion became even more concerned with how ignored the species was in conservation circles. It seemed, to him, like crazy negligence��on behalf of the government, environmental groups, and anyone��who loves marine mammals. Why wasn’t more information available for a general audience?��

“More than I want to see one, I feel pretty obligated to share, now that I know the story as well as I do,” Campion says. “If people don’t know about them,��we’re not going to be able to save them.”��

Conservation efforts are often dedicated to charismatic megafauna like whales,��and publicity campaigns often hinge on a visual representation of how the appealing creature is being harmed. It would seem that North Pacific rights are ignored mostly because they are so rarely sighted, even compared to their close relatives.��An interesting analogy to the North Pacific rights’��place in species-protection efforts are North��Atlantic rights, which have��become a celebrated figurehead of marine-mammal conservation. Nearly all North��Atlantic rights have been identified and are carefully tracked by human beings. We know what’s going on with them, their plight is highly visible to researchers and the public, and the public seems to adore them. “Every time one of those whales died, there would be a New York Times story,” Campion says. “Even West Coast news organizations would mention Atlantic whales—it’s crazy.”��

If people don’t know about them, we’re not going to be able to save them.

Conservation groups have designated 2020 as the year of the right whale��family, but that campaign focuses on the less threatened North��Atlantic species. In 2013, NOAA issued a formal ,��but so far it’s largely been a nonstarter. Even in circles focused on identifying and protecting whales, the North Pacific right seems invisible.��

Once Campion’s film is done, he plans to launch other initiatives, like a postcard campaign to the Department of Commerce,��which, in addition to NOAA, is partially responsible for the recovery plan.��“No one has been hammering on it,” Campion says.��NOAA has received funding for inexpensive projects, like maintaining the acoustic recorder on Peggy, but it isn’t enough for large-scale vessel surveys and fieldwork.��

Campion admits that positioning himself as an advocate for��an enigmatic, struggling species is exhausting. Sometimes it feels like screaming at a wall, he says. But he doesn’t want to give up on his quest to save the rarest whale in the world.��

“These whales are very likely going to go extinct, potentially in my lifetime,” he says, “It seems like��telling this story��is what I can do right now.”