My Father’s SOS—From the Middle of the Sea

Richard Carr, a retired psychologist who had long dreamed of sailing around the world, was in the middle of the Pacific when he started sending frantic messages that said pirates were boarding his boat. Two thousand miles away in Los Angeles, his family woke up to a nightmare: he might be dying alone, and there was almost nothing they could do about it.

New perk: Easily find new routes and hidden gems, upcoming running events, and more near you. Your weekly Local Running Newsletter has everything you need to lace up! .

My father’s e-mail didn’t make much sense, but he seemed to be saying that pirates had boarded his boat. “Being kidnappedby filmcompany Deep south blackcult took over steering,” it read. “Ship disabled.”

He sent this to my mother, Martha Carr, at 4:30 a.m. Pacific time on May 28, 2017, a Sunday. She was at home in Los Angeles, asleep, and she wouldn’t see the message—and a couple more like it—until 8:30 a.m. For several hours, my dad, 71-year-old Richard Carr, must have thought they weren’t getting through.

Dad was in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, on his way from Puerto Vallarta, Mexico, to the Marquesas Islands, 26 days into a single-handed, 2,780-mile crossing that was to be the first major leg of a lifelong dream: sailing around the world. It was 3:30 A.M. where he was, near the equator, an hour behind Pacific time. He was 1,160 nautical miles from the Marquesas, 1,975 from Hawaii, and 1,553 from Mexico—about as far away from land, and help, as you can get.

His boat was a 36-foot Union Cutter called Celebration, built in 1985. It had a white hull, faded teak decks, brass portholes turning turquoise, and forest green sail covers that always reminded me of summer camp. Climbing into the cabin was like disappearing into a hobbit hole—a dark, welcoming space with oak cabinets and big cushions.

Just six hours before Dad sent the pirate alert, late in the evening on May 27, he had used his satellite text messager and tracking device to wish Mom a happy 39th wedding anniversary. He also wanted to ease her concerns that his boat was pointed the wrong way, something she’d noticed on a map that indicated his position based on the messages he sent.

“Hey Hon. I’m fine,” he wrote. “I have enough food, etc. The watermaker is still working. Pulling over & parking in a storm (heave to) is a good skill to have & practice.” He signed off with a smiley face.

The smile was gone now. Ten minutes after his 4:30 message, he e-mailed one of his younger brothers, John Carr, an aerospace engineer in Orange County. “Being kidnapped by pirates,” he wrote. “Talk to martha.” John was asleep, too, and didn’t see it.

About two hours later, Dad followed up with this message to John: “Apparently, I’ve been spared.” A few minutes after that, at 6:54, he messaged Mom: “Hugewind pirates left. I’m fine. Talklater.” He said he’d sent out an SOS and an alert from his EPIRB, an emergency device that transmits a satellite signal to rescuers when a boat is in distress. He asked her to call and cancel them.

I was nervous, but I also understood the exhilaration he felt on the water, and I was proud that Dad was going for it. I knew there was a chance that he wouldn’t come back, but I’d rather he try—risk and all—than live with regret.

At 7:54, shortly after sunrise where Dad was, he wrote Mom: “Message me as soon as u can. I’m really shaken.” Then he tried John again: “Very scarey. Thought I would not see day.” For Dad, sunrise meant nearly 13 hours of sitting in humid 80-degree weather in the doldrums—an area near the equator with fickle conditions that leave sailors becalmed one minute, huddled in squalls the next, and then scrambling to catch a big gust of wind.

Around eight in L.A., Mom went outside to do some gardening before it got too hot. She still wasn’t aware of the e-mail Dad had sent. “Richard usually messaged me in the afternoon, and I would write back,” she told me later. “So I didn’t check my e-mail when I got up.”

At 8:30, the phone rang. It was John calling to discuss the strange e-mail he’d received. She ran upstairs to her laptop. It was then, roughly an hour after Dad sent his final message of the morning, that he finally heard back from the family. Mom’s first message to him said: “Omg-what do u need? Are u ok?”

She phoned my brother, Tim, who lives in Culver City, about 45 minutes from her house, with his wife, Jen, and their two young boys. Tim messaged Dad, asking if he was all right and giving him instructions for canceling an SOS. Then he drove to Mom’s. Once there he called me in Woodstock, New York, where I live with my husband, Ian, and our two small daughters.

Before leaving, Dad had given Mom a list of emergency contacts. She called a California branch of the Coast Guard and was advised to try Honolulu instead, because that part of the Pacific is their territory. A woman answered. After listening to the details about Dad, she checked for an EPIRB alert from him. When she came back, she said, “There’s been no signal.”

What was going on? There were various possibilities, and none of them seemed good. We scrambled to find answers, knowing there might not be much time.

Richard Carr grew up in the 1940s and ’50s near the Erie Canal just outside Buffalo, New York. As was typical in that area at that time, he was one of seven kids in a hardworking family with stern parents, all of them crammed into a three-bedroom house.

The boys in the family were often out all day, until dinner, and Richard was no different. He taught kids to swim and fish for the local Boys’ Club and built a canoe with his older brother to explore the canal’s feeder creeks. He and his best friends played Lost Boys along parts of the Niagara River, when he wasn’t diving in it with members of the scuba club he started.“He was an optimist,” my uncle John recalls. “He always had the outlook that there was something to do and it was always good.”

In 1963, Richard was offered a full scholarship to study marine biology at the University of Miami, but his father refused to divulge the family’s income on the required forms, so the aid fell through. Ready for some distance from his hometown, he caught a free ride to L.A., where he took classes at a community college to make himself eligible for residency tuition at California universities. To save money, he worked at a Laundromat and sometimes lived off ketchup packets mixed with water. (“Tomato soup,” he joked.) He was shy, but he had a sunny, magnetic smile.

Mom saw him for the first time in 1969, at Oakwood, her private high school in L.A. Born Martha Gold, she was a popular tenth-grader, with long red hair, parents who worked in the film industry, and a horse that she jumped in competition. Dad was interviewing to teach seventh-grade science. By that time, he’d earned a degree in anthropology from UCLA and was interested in psychology. They didn’t start a relationship until 1975, when Mom was at UCLA as a psych major. They met in a professional group, and though Mom declined his invitations for a while, she finally gave in and agreed to go out with him.

“I was an anxious person and didn’t have a lot of relationship experience,” she says. “He helped me work through my resistance and wasn’t put off by my weaknesses, so that showed me a lot about his devotion.”

They married in 1978; by the next year, Mom was pregnant with Tim. Dad, who had learned to sail in California, sold a boat he owned—a 31-foot Mariner ketch called Cortez—and bought an old Spanish-style house in the San Fernando Valley, where Tim and I grew up and where Mom still lives. My parents were busy raising us and tending to clients in their therapy practices, but sailing was always on Dad’s mind. He often tried to convince Mom that the family should sail around the world together, but she wanted her kids to have a normal upbringing.

My parents shared an office suite in Hollywood, across from the famous Capitol Records building. As a kid, I’d sometimes sit in the waiting room while one of them finished a session. I’d sort my Mom’s tea collection and watch gem-toned fish flit about in Dad’s saltwater tank. Over the years, in addition to his practice, he became deeply interested in research. He explored the neurology of babies in the womb and wrote a book about the .

Though Dad was devoted to his work, our coffee table was never without an issue of . On some weekends during my childhood, we sailed a rented boat to Catalina Island, a half-day’s trip from L.A. We often camped and skied, and also traveled to Hawaii, snorkeling and listening to Dad tick off the names of the fish we’d seen.

More recently, as he prepared to depart on his circumnavigation, I thought about taking sailing lessons and joining him somewhere tropical. Father-daughter time felt sacred by then, because we hadn’t lived in the same state for almost ten years. The occasions we spent together—a ski trip to Mammoth, a daylong sail off Los Angeles Harbor—established our dynamic. We dipped comfortably into troughs of silence crested by deep conversations about life.

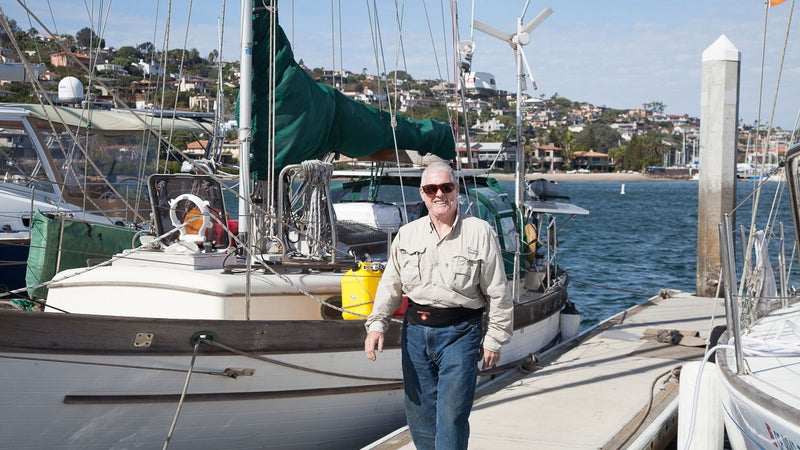

Dad’s quest to sail the world got serious on March 16, 2010, when he made the final payment on a boat he found in the San Francisco Bay Area called Celebration. It had a crack in the bulkhead, a rusted mast step, and a hull full of blisters. He planned to devote the next few years to readying it.

The boat had been known as Pelican, until the previous owner changed it. According to legend, renaming a boat enrages the sea gods if you neglect to do various ritualistic things, like burn the old ship’s log. I have no idea if the prior owner adhered to that tradition, but we do know that he made it only as far as San Diego on his own around-the-world attempt. There he suffered a stroke and was sidelined. Seven years after purchasing the boat, my dad bought a carved pelican figurine at a stop in La Paz, Mexico, and mounted it in the cabin as a talisman.

During the summer of 2010, once Celebration was fit to use, it was temporarily docked in Oxnard, 60 miles northwest of L.A., and my parents spent weekends sailing to the Channel Islands. Mom enjoyed the trips but had no interest in big ocean crossings. Instead of joining Dad on his circumnavigation, which would play out in stages over several years, she planned to meet him in various ports around the world.

That fall, Celebration found its new long-term home in busy, industrial Los Angeles Harbor, at a small, homey marina called . It was tucked into the terminus of a maze of massive cranes playing Tetris with container ships.

Dad spent weekends fastidiously working on Celebration, but eight hours a day was a lot for him. “He wasn’t a carpenter or a mason or a plumber,” says Thor Faber, a boat repairman who sold Dad equipment to prepare for long sails. “It’s taxing for somebody who is 40 or 50, but for someone who is 60-plus it’s a big adventure.”

At first the trip was a dream. “Lovely light air sailing,” he wrote. It filled me with relief and joy to know that, after years of hammering and tinkering, the boat was finally living up to its stout reputation.

Still, Dad couldn’t stay away, and the more time he spent on the boat, the more obsessed he became with getting everything done. When his professional work got in the way, he grew frustrated and cranky. Marty Richards, Dad’s liveaboard neighbor, says he could never suggest a fix for something without inviting a lengthy back-and-forth.

“Your dad was a stubborn guy,” he told me. “Kind of a self-taught guy, and I think he pretty much lived his whole life that way, right? He wouldn’t take anything on faith unless he could understand it intuitively. He just wouldn’t believe it.”

Dad hoped to depart in late 2015, but an El Niño weather forecast loomed for that winter. Plus, the boat wasn’t seaworthy yet. The delays felt monumental to him. It was as if sticking to the schedule was the primary goal, and he couldn’t see that being patient would allow him to practice and prepare. I think he also sensed that, at this stage of his life, getting ready for such a trip might require more time than he had left.

Mom became anxious as the departure date got closer. Their lives had been intertwined for decades, and he was about to leave on a voyage that could go on for years. The repairs—which came to nearly half the cost of the boat—caused frequent arguments. But she had to accept that he wasn’t going to give up his dream, so they moved forward, at times clumsily, toward his ultimate adventure.

The start of 2016 brought a major new expense: ������������پ��Dz�’s decks were rotting and had to be replaced. After that repair was completed, in Marina del Rey, Dad motored down the coast toward L.A. Harbor. En route, the engine started smoking, and it blew a head gasket, requiring a partial rebuild. Crucial time to test gear and practice single-handing was slipping away.

Finally, Dad refused to delay any longer. He forced himself to get going by signing up for the , a two-week cruising rally with 130 other boats that ran from San Diego to Cabo San Lucas, Mexico, at the end of October. He would go with his marina mate Marty Richards.

Dad and Richards made their way to San Diego, and the whole family gathered there to say goodbye. Mom kept her nerves under control by orchestrating dinner. Dad’s anxiety peaked as he tried to clear years of collected junk from Celebration—piles of pencils, rulers, and other dead weight.

I was nervous, given Dad’s track record with mishaps like the overheated engine, which required a Coast Guard tow. But I also understood the exhilaration he felt on the water. Over the years, as part of my career, I’ve snowboarded backcountry terrain and climbed in the dark with thousands of feet of exposure. I was proud that Dad was going for it. I knew there was a chance that he wouldn’t come back, but I’d rather he try—risk and all—than live with regret.

One night in San Diego, after the kids were asleep, Tim and Ian went to the hotel bar. A sailor there started talking about pirates along the African coast, an area that Dad would eventually find himself in as he sailed around the world.

“That really alarmed us and made us question if Richard knew what he was doing,” Ian remembers. “We were crying into our scotch. We knew he was going no matter what.”

“I remember feeling impressed at how brave he was and proud of him for going, but I was also terrified,” Tim says. “I gave him a hug on the boat and told him I was afraid he wouldn’t come back.”

When it was time to pull away from port, Mom ran off briefly to put something in the car. When she got back, Celebration was gone. “That was when I really started to worry,” she says. “How could he forget to say goodbye?” She called his mobile. After fueling up, he turned around, docked, and said a proper farewell before rejoining the rally.

Problems ensued as Dad and Richards made their way south. Among other things, they had to fix a leaky bilge pump, which had caused an alarming amount of steam to pour from the engine compartment. New noises kept Dad awake on the first night. “He was so sleep deprived he was slurring,” Mom recalls of their phone conversation the next day. “His thoughts were all over the place.”

And his eyes were playing tricks on him. At one point in the night, he thought he saw a forest of trees rising from the water, illuminated by phosphorescence. “Despite knowing they couldn’t be real,” he wrote later on his blog, “I had to wait … and watch the branches dissolve into fragmentary illusions.” Hallucinations worried us, but we also knew that they’re not uncommon among sailors on overnighters.

Even so, Dad had some hard things to face. “The real journey, which had been more challenging than my conjured fears before we started, left me needing to reflect and redefine my trip,” he wrote. “Questions tormented me… When Marty’s gone, who will I talk things through with? How will I hold up sailing day and night on long runs? Am I really ready to single-hand this trip? A reality that had been an idea just a few days before was unfolding according to its own design as the life I’d agreed to.”

Cabo Corrientes, rocky and pointed like an arrowhead, is the last piece of land jutting into the Pacific at the base of Mexico’s horseshoe-shaped Banderas Bay. Head east and you’ll hit Puerto Vallarta, the bass-thumping spring-break destination. Head west and you’ll hear nothing but wind and the slap of the ocean against your hull.

I can picture Dad clearing that spot on the morning of May 3, 2017, his hands loosely gripping the boat’s metal wheel and his blue eyes surveying the horizon. He would have uttered an “m�����” to mark the moment before he went back to winching and charting and setting angles. “My sea journey has really begun,” he texted as he moved out. “Only ocean to the Marquesas. Lite winds. Breakfast time.”

The huge expanse ahead would be his first ocean crossing, and it would also be the hardest leg of his planned route, judging by the likely weather patterns and duration—an estimated 27 days. When I asked what scared him most about the trip, he said it was sleep deprivation, an inevitable issue for single-handed sailors, who often are so busy that they can rest only in chunks.

Dad had spent the month and a half before departure in La Cruz de Huanacaxtle, prepping to join the , a migration of boats that cross from the Americas to French Polynesia, mostly during March and April, when the winds are strong and storms are rare. But April came to a close, and he still had repairs to make. Fortunately, the weather window remained favorable for a few extra weeks, and there were at least a half-dozen boats crossing at the same time. On May 2, the birthday of his first grandchild, Brendan, he set sail.

Celebration, a slow but sturdy boat, was equipped with solar panels, a wind generator, a watermaker (or desalinator), a four-man life raft, a self-steering device, a flare gun, a $1,300 survival suit designed for dangerous Alaskan fishing conditions, and provisions for three months, among other items.

“It’s an easy boat to handle,” says Mike Danielson of PV Sailing, a Puerto Vallarta–based marine service center that helped Dad rig. “If you’re in a gale, that boat can heave to and weather it out.”

Heaving to—a maneuver used to slow a boat’s progress and basically park it—is a skill Dad would practice often on this trip, especially when he was in the Intertropical Convergence Zone, where the north- and southeast trade winds meet near the equator. This region is infamous for chaotic weather that alternates between rain squalls, shifting winds, thunderstorms, and dead calm. The patterns become more frenetic as summer approaches. “It’s feast or famine out there,” says Danielson. “Getting across the convergence zone at that time is a lot of work.”

I was due to have my second baby a week before Dad’s estimated arrival in the Marquesas on May 29. Both of us would be facing difficult challenges thousands of miles apart—me in labor, him single-handing—and that made me feel close to him. Our family had preliminary plans to meet in New Zealand for Christmas.

On May 3, as Dad sailed west and Cabo Corrientes slipped below the horizon, my water broke—three weeks early. Later that day, I delivered my second daughter, Wyatt.

“Congrats on new daughter,” Dad wrote the next morning. “Delivered with your special drama, flair and courage to do all U can.” As he headed into the empty Pacific—wishing he’d been present for Wyatt’s birth—seven birds kept him company, perching on the bowsprit, falling, scrambling, honking, and perching again.

At first the trip was a dream. Every few days, Dad would let us know how great the conditions were. “Lovely light air sailing,” he wrote. It filled me with relief and joy to know that, after years of hammering and tinkering that had left Dad’s hands greasy and raw, the boat was finally living up to its stout reputation. He was really doing it.

Eventually, the seas got bigger and rougher. Dad’s self-steering wind vane—which allowed him to leave the helm to cook or clean or sleep—was overwhelmed by winds and swells, and he had to stay on deck and help steer. Exhaustion set in, and the less than ideal wind direction he was trying to harness required vigilance.

By the time he was ten days in, averaging a slow, steady 80 to 90 nautical miles per day, he was getting to know himself in isolation. He told Mom that he was having a lot of internal dialogue, which for him was a normal way to deal with demanding situations.

As the days went on, the frequency of Dad’s messages slowed, as did his forward progress: he was making only 77 miles a day now, and his overall trip time was recalibrated to five weeks. Because of rough seas, he was having trouble eating without spilling. Worse, his watermaker had stopped functioning shortly after he left Banderas Bay. Mom relayed repair notes from Thor Faber; after two weeks, during which he probably drank from the backup supply, Dad got it working again.

In his third week out, on May 20, he wrote that “gear & wind & wave” had knocked two pairs of glasses off his face, leaving him with a single damaged but wearable pair. “A bit scarey couple of days,” he said. “Adveture & learn or die trying ;}};.” He followed with this cryptic note: “Horizontal winds that turn ranbows sideways pose question of how does one sail in that? Very carfully!”

For days the weather flopped between foul and calm. On May 26, two days before Dad sent his first message about pirates, he made a sharp turn south toward Hiva Oa—the second-largest island in the Marquesas—but storms blew him back 20 nautical miles.

“No joy!” he wrote. He told Mom that he was reevaluating everything. “It’s the whole plan,” he said. “Boat and I r not really going.” His next message read: “Damn t.” The weather router had just told him it would take 24 to 48 hours for the winds to become more favorable.

In the doldrums, time slows down. Explorer Jason Lewis, who has sailed in that part of the Pacific, described it like this in Jonathan Franklin’s book , an account of the saga of Mexican fisherman Salvador Alvarenga, who survived being lost at sea in the Pacific for well over a year: “The lightning comes down to the water. You’ll see these thunderstorms developing, and they’ll be very dark and foreboding. You watch them for hours, rolling toward you. … Every day out there feels like a week … and every week feels like a month, a month felt like a year.”

In the same book, explorer Ivan Macfadyen says: “If you start to imagine saber-toothed tigers in the corner of the room, then suddenly they’re all over you. The fear factor is overpowering.”

At this point, the Coast Guard requested that he type a simple Y or N to this question: “Is your life in danger?” “I believe so,” Dad responded. A few minutes later, he wrote to our family: “Goodby.” “You come home! NO!!!” Mom begged.

Dad was never a complainer, but he was worried about the calm conditions. “This not a little thing,” he texted. “It’s over a week of lite adverse winds.” His fuel tank was nearly full—he could have motored most of the way to Hiva Oa—and he seemed to be forgetting that the weather wouldn’t always be like this.

“Big challenges going on,” he wrote on the 26th. “I need some new ways of approaching them. Strangest thing just happened. Too odd & Long for InReach. Involved scam moviemaking.”

Mom, alarmed, responded within minutes: “Scam moviemaking? Are you in contact with others? Food and water holding out?” She told him she wanted to hear more about the challenges he faced. He didn’t respond.

On the afternoon of May 27, around 1:15, he wrote: “Rain—Intense at times, moments horizontal. my decks are relatively clear, not sails. Happy Anniversary 39 years of bliss. Re movie scam. Maybe my Beautiful Mind ala My Sailing Mind. Take this as possible book idea. As real dilemma. After2 days sleep dep, Banderas Bay, Shortwave radio playng unknown to me made me think I was in trouble. Then thought to check it. Had a laugh.”

Mom wrote back: “Happy Anniversary Lover! I wondered if hallucination re Movie Scam but thought maybe u r listening to something bizarre over shortwave…SLEEP!”

Then she got the message that made it clear his boat was facing the wrong way. “I was in rolling seas, storm cells encroaching & gusts to 28Knts, so I heaved to,” he wrote. “Parked. Big storm Moving north.… Adverse til next Friday. Can u believe it. Obstacles at almost every step. The communication difficulties o”

The text ended there.

On the morning of May 28, once Mom had read the “deep south blackcult” pirate messages, the family started reaching out every ten minutes: “Are you okay?” “On phone with coast guard.” “Trying to find you.” “PLEASE ANSWER.”

We got nothing.

The Coast Guard tried to raise Dad by text, but he didn’t reply. Tim wrote: “Please respond to John Mom or Ali ASAP.… Want to know you’re safe and unhurt. Maybe you’re sleeping?”

Four hours of silence passed before Dad emerged at around 12 p.m. his time. “It’s part of being put in my pjace Southern style,” he wrote. “More later.”

But nothing followed that provided any clarity. Instead, roughly an hour later, he wrote: “I’m fine now. One of those nearby fishing boats was in empjoy of a southerq boss. Who, unbeknost to me, wanted to put me in my place. Long story.”

Why was he being so murky? Had he been kidnapped by pirates and someone else was sending these messages? Was he trying to communicate in code? Mom asked for his radio frequency so she could relay it to the Coast Guard in Honolulu. “You need to reply … NOW. What you are saying makes no sense. Anything stolen?” The Coast Guard messaged boats in the area via satellite, asking them to keep a look out for Celebration.

An hour went by before Dad said he’d try the Coast Guard over the SSB, a long-range radio favored by open-ocean sailors. He apologized for not responding, then said: “Nothing stolen No one hurt, No info on boat. Was inside deciding best action.”

We were relieved but confused. Would pirates allow him to stay inside to review his options while they were aboard?

At 2:55 p.m. Dad’s time on the 28th, after he reported that the radio channels were occupied, Mom sent him the Coast Guard’s e-mail address and wrote, “I have been hysterical today. Tim with me all day. What did the fisherman do exactly? Also, what language?”

At 3 p.m., the Coast Guard texted him again. He sent his coordinates—N 6 35.9712’ W 127 17.7952’—and then messaged them: “This is vessel. Celebration WDJ4510 needing to confirm cancellation of epirb 2DCC7B512CFFBFF this morning 5/28/17 around 6:30AM. Cannot reachUSCG on SSB.”

Tim let Dad know that no emergency signal had been sent or received, adding that we were glad he was OK but this was scary for everyone. He signed off: “Love you!!! Be safe.”

We were still baffled. Dad’s abrupt shift—from giving us vague information about pirates to providing lucid housekeeping details to the Coast Guard—made no sense. Why couldn’t he be clear about what had happened to him?

An hour later, he wrote Mom: “Still may be in trouble if myinfo gotinto public record.” She responded that nothing had been made public. At 5:08, he told the Coast Guard: “I’m sea beigwatched.”

“We don’t understand your message,” they replied. “Are you in distress? Did anyone come aboard your vessel? What is deep south black cult?”

Tim’s wife, Jen, wanted to confirm that someone else wasn’t pretending to be him. “Tell me something only you would know about me. What do I do for a living?” she wrote.

“Physical sports therapy,” he said. Correct.

Mom pressed for details about the pirates, with minutes passing between responses. “We spoke about Phyllis’ disability She’s retarded or speech disabled,” he wrote, referring to someone we’d never heard of. “She thought Iwas afriendwho should stay. I refused.”

“Who spoke with you about Phyllis?” Mom asked. “Was she related to one of the fishermen? I have no context. This sounds bizarre. Did they board your boat? Threaten you?”

“I luv u always,” he said. “Marni ashes buried at sea Al’s too.”

That was a gut punch. Marni and Al were Mom’s mother and stepfather. They’d both died in the two-year period before Dad sailed. One of his goals was to spread their ashes in the ocean.

“When I saw that message, I thought, Uh-oh. He’s going to do something,” Mom said later. “It was like he was taking care of business.”

A year earlier, Dad was sitting bedside with my mom’s mother as she lay dying of cancer, her body withering into a feather. “I don’t know how to die,” she whispered.

“You don’t have to. Your body knows what to do,” he said into her ear. “You can choose to go anywhere else in your mind. Think of a childhood memory, think of something that you love.” She thought of a camping trip with her sisters. A few hours later she was gone.

Now it was Mom’s turn to talk to him. “Thank you sweetheart,” she wrote at 6:06 p.m. “I am feeling alarmed you aren’t responding to my other questions. It’s safe to send message. Do u want to go to Hawaii instead?”

Three minutes later he responded:

“Killers. Watch yourback sorry…”

A few minutes after that:

“Hawaiisoundsqood barbeque at sea.… Sorry about insuance.”

“WHAT ARE YOU DOING?” Mom wrote. “You are scaring me. What is happening? Sounds like you are going to hurt yourself! Do you need help? Say yes or no.”

“Thesepeople r killers it’s nott beautiful mind,” he said.

All that day, Dad had moved, slow but steady, on his southwesterly route toward Hiva Oa. But now the map, which updated his position with each message, showed him heading due west. He was drifting off course.

At 6:59, he wrote: “Hekilled hisdaughter well not himhis aid. Poison crack. She’s dying These r old south. People will say I sucided. Better thanwhat he intends,I’ll wait. Miss u.”

“Is your ship disabled?” Mom wrote. “Company?”

“No not in significantway. Listen talk speakers with remote personne.”

“Listening on radio? Who is talking to you?”

“Listeningtome&hisdaughtr talk& re-porting back.”

My sister-in-law broke in, saying she was worried. “So am i notlookingto die,” he wrote. “Don’t want to be killed or enslaved.”

At this point, the Coast Guard requested that he type a simple Y or N to this question: “Is your life in danger?”

“I believe so,” Dad responded. A few minutes later, he wrote to our family: “Goodby.”

“You come home! NO!!!” Mom begged. Ten minutes later, he said, “I’D loveto-buthearboats&Needtoact fast.”

Over the next hour, his responses slowed. At 8:48, Tim wrote: “Satellite shows nearest boat is many many miles away. This isn’t just a lack of sleep right?” At 9:08, with no new message from Dad, Tim begged: “Hit SOS please.”

Family members kept messaging late into the night, but no one heard from Dad after 8:30 his time. The final e-mail from him read: “Not able stop Patjustgot news she’s toberescued&instijtutionalized byher- boy friend.”

All this was happening in the late afternoon and evening where Dad was. In New York State, I was four hours ahead. The last I’d heard, from the message relayed by Tim and Mom (“I’m fine now”), he seemed OK. By the time the situation started deteriorating, I was asleep for the night with our new baby. Mom didn’t know which messages were getting to me, and she didn’t call because she knew it was late on the East Coast.

At 2:30 a.m. my time on the 29th, I woke up to feed the baby and decided to check my phone—something I usually don’t do, but I felt an overwhelming need to message Dad, to let him know I was sending love.

The next morning, I found this e-mail from Mom. “I know you will be getting up before us and will see some scary e-mails from dad last night,” she wrote. “Coast guard says there are no boats near him. He sent us a few more e-mails after the one that says goodbye. But we don’t know what this means yet. We will loop you in as soon as we are up. Just hope he didn’t do something stupid out of paranoia. We messaged him to go to sleep. Hope he read.”

I called Mom and Tim and asked them to forward the messages. What I read looked schizophrenic. I studied them over and over; the fear in his words was tangible.

The Coast Guard hadn’t been able to find any instances of piracy in the area where Dad was. Later research, using records from the , showed that of the 204 reports of piracy and armed robbery worldwide in 2017, only three occurred in the region where Dad was sailing. All involved large container-style ships and had happened in Peruvian and Ecuadorean ports.

By the end of the day on May 29, we hadn’t heard from Dad for 24 hours. During a conference call with the Honolulu Coast Guard, I asked about the possibility that he had run into hostile fishermen in the early-morning hours of the 28th.

“Maybe he crossed their nets and they had to come on board to detangle his boat in the middle of the night,” I said. “That would be terrifying—it would be dark, he hadn’t seen people in weeks, and most likely they spoke another language and were angry.”

The Coast Guard didn’t rule it out.

Another question loomed: Had anything at all happened to him? Dad said he’d sent EPIRB and SOS signals, but he hadn’t. And what had he meant by “barbeque at sea”? The message “sorry about insuance” showed up immediately after that. Was he telling Mom that she wouldn’t be able to collect insurance money because there would be no body to recover?

This was so far from how I envisioned Dad leaving this world. I yearned to know what his face looked like, what his heart felt like in those rawest of moments. His words didn’t tell us. As darkness fell around me on the 29th, my mind looped the same haunting questions: Dad, where are you? What did you do?

At noon on May 28 in California, as Mom and Tim were waiting for a sign of life from Dad, the Coast Guard had asked about his mental-health history. Mom told them that he’d never had any problems. But judging by his reaction to sleep deprivation during the Baja Ha-Ha, she said, he may have been delusional from exhaustion.

The Coast Guard began scouring for resources—boats, planes, anything—to get eyes on him. The nearest boats were 200 nautical miles away, more than a day’s journey. A cargo plane could have reached him, but he was so far out that the crew would have only ten minutes to search before they’d need to turn back.

At 11 p.m., a staffer at DeLorme, the maker of Dad’s texting and tracking device, confirmed that it had stopped accepting messages at the exact moment he’d sent his final one. The device had either been turned off, malfunctioned, or been destroyed.

At 1 p.m. on Monday the 29th, the Coast Guard reached the U.S. fishing vessel –American Enterprise, which was 140 nautical miles southeast of Dad’s last known location. The skipper agreed to head to that position immediately.

To construct a search grid, the Coast Guard uses a program called the Search and Rescue Optimal Planning System. It gathers information such as a boat’s size and -location, plots 5,000 corresponding points on a map, and creates simulations of likely drift patterns. The Coast Guard usually sends a boat or plane to cover these drift points -immediately. If it can, it drops a self-locating data-marker buoy, which uses the current to validate the system’s predictions. In Dad’s case, he was too far away for either of those options.

I’ve pictured Dad in an altered state: eyes glazed over, stoically moving about the boat as he completed necessary tasks, or maybe he was sobbing—heartbroken to know he would never see his family again.

Through all this, my family tried to figure out what else we could do. Mom e-mailed the Tahitian authorities. I called the most experienced sailor I knew. He suggested I try to contact fishing and commercial vessels in the area. Uncle John scoured real-time ship traffic online. Mom asked if there were any satellites taking pictures that might show us the boat or, worse, its debris. (There weren’t.) Tim e-mailed the IMB Piracy Reporting Center. But everything we were doing had already been tried by the Coast Guard.

On the evening of Tuesday, May 30, American Enterprise, along with its onboard helicopter, began a grid search southwest of Dad’s last known location. By the evening of May 31, three days since we’d heard from him, they had searched an area the size of Connecticut, with no sign of either the Celebration or any debris.

Meanwhile, a 688-foot Panamanian boat joined the search 240 nautical miles to the southeast—an area where the Coast Guard hypothesized that Dad might be. No sightings were reported.

By June 2, we were becoming desperate. We knew that Dad, even if he was still alive, probably couldn’t survive much longer. On June 4, a week since we’d heard from him, two more boats searched but saw nothing.

A day later, there was a glimmer of hope: the Coast Guard’s satellite data showed what looked like a sailboat headed south, which aligned with initial hypotheses about the boat’s course. Its length and color matched Celebration. The Coast Guard speculated that the boat was harnessing the trade winds south and would make a hard right at Hiva Oa’s latitude.

Unfortunately, by the time satellite data hits the Coast Guard’s desk, it’s 24 hours old, making a moving target nearly impossible to find, especially among scattered clouds and whitecaps.

American Enterprise, which was now the closest ship to the unidentified boat, sent up its helicopter again. The crew saw nothing.

On the 6th, the Coast Guard queried Tahitian hospitals to see if Dad had been brought in. Negative.

On June 8, Dad’s 72nd birthday, the Coast Guard again spotted an unidentified boat along the southern course—about 30 degrees off a Marquesas route. It was getting closer to Hiva Oa, traveling at four knots. Assuming it might be the same boat as before, the Coast Guard used the new data to create a third potential position.

Finally, on June 13, two weeks after my dad’s last communication, the unidentified boat was close enough that the Coast Guard deployed a plane from Hawaii.

After staging in Tahiti for a day, the C-130 Hercules would fly out, loaded with a communicator, a life raft, and other droppable supplies. The eight-hour round-trip flight would leave only two hours to search at the site, but at least it was something. The Tahiti coast guard’s Falcon surveillance plane would also search.

On the 15th, the planes took off from Tahiti. They scoured the boat’s path. Three vessels were spotted, and one remained unidentified, because it had no electronic signature. However, it didn’t match the description of Celebration, and radio contact confirmed that it had two people aboard.

Subsequent searches found nothing, and on June 21 the Hercules was sent back to Hawaii. On June 22, the Coast Guard suspended the search. All told, it had covered 59,598 square miles over 24 days.

In the 17 months since Dad vanished, no trace of his boat has been found. I doubt it ever will be—although one drift-analysis expert suggested that, if Celebration is still floating, it could hit New Guinea in two years. But I believe that the boat—or what’s left of it—is at the bottom of the Pacific, with Dad’s last coordinates serving as his only headstone.

I’ve spent hours trying to imagine what happened in the end. I’ve pictured Dad in an altered state: eyes glazed over, stoically moving about the boat as he completed necessary tasks, like dealing properly with my grandparents’ ashes. Or maybe he was sobbing—heartbroken to know he would never see his family again. Then he either set the teak deck on fire or cut an intake hose, filling the boat with water and sinking it.

If he did any of these things, it was because sleep deprivation had driven him mad, making him believe that suicide was the only way to escape the pirates he’d conjured, the only way to prevent them from killing him.

He didn’t have a gun on board, as far as we know, so he would have died either by fire or in the sea. Did he stay on deck as flames rose around him? Tim doubts it. He thinks Dad started a blaze, dove off the side, and swam straight down. I picture mottled moonlight reflecting on his pale skin as he descends into darkness.

The idea that sleep deprivation made Dad take drastic action may sound fantastical, but there are countless precedents. It’s known that exhaustion, fatigue, and isolation at sea can create extreme levels of delusion. Experienced sailors told me stories of mates who were rendered incapacitated just a few hundred miles offshore, with no obvious cause.

One of the most famous sailing mysteries is the case of Donald Crowhurst, a Briton who single-handed in the 1968 Golden Globe around-the-world race and never came home. He set sail on October 31—the same date Dad set off from San Diego—and was out for 243 days before he succumbed to mental collapse, writing a 25,000-word manifesto on the subject of the cosmic mind and why he had to leave this world. His boat—and log—were found floating in the Atlantic Ocean.

John Leach, a professor with the Extreme Environmental Medicine and Science Group at the University of Portsmouth, England—and an avid sailor and former military psychologist who specializes in prisoners, hostages, and others who’ve experienced isolation—described the perils of survival in the book 438 Days: “It’s okay living inside your own head, provided it doesn’t slip into psychosis.”

“He always felt like we got the life I wanted, not the life he wanted, filled with adventure—diving and sailing,” she says. “The fact that he went off on this trip felt like I wasn’t enough. Ultimately, the boat won.”

When I speak to Leach about my dad’s case, he describes to me how a mind can become unmoored. “Psychosis in simple terms is a breakdown in reality,” he told me. “When you are in isolation, and sleep deprived and water deprived, which I suspect he would’ve been, you take in the information around you and interpret it to fit the model in your head. If he thinks he’s being chased, he’ll hear waves and the wind as engines.”

The cluster effect of sleep deprivation, dehydration, fatigue, duress, and perceptual and sensory deprivation could have resulted in cognitive disorganization that was reflected in his language, Leach explains. In other words, Dad’s signals may have been misfiring, skewing his perceptions. And the timing didn’t help.

“There is something around about the three-week period in isolation that I’ve recorded too many times to dismiss,” Leach says. “Even people without psychiatric problems get a sudden crash psychologically, and for the first time they start thinking about suicide.”

My mother, sure that Dad was suicidal, had tried to reply to him in ways that would bring him off the ledge.

“Your dad used to tell me that the brain is the only organ in the body that doesn’t tell you when it’s malfunctioning,” she says. “I was afraid to say to him that’s what I thought was happening—that it was a hallucination—but I couldn’t figure out how to do it. I didn’t want him to feel abandoned and stop talking. Hearing each other through a sat phone would have helped, but he didn’t have one.”

When I ask if she has regrets, she laments not being more involved. “I felt so angry about him wanting to do this and spending so much money and he was going to leave me. I had to say, This is just his,” she says. “I didn’t want to go but I didn’t want to be alone, either. And he would’ve resented me if I had said, ‘You are not going.’ ”

Distancing herself mentally from the boat, the trip, and the departure date was a coping mechanism—the less she had to do with it, the less fearful she was. But she still wanted to be a brave, supportive wife, so she helped by packing and provisioning the boat in San Diego. Now she wonders if that was enough: “If I had educated myself about what he would face out there, I might have been more persuasive about him not going alone.”

Then Mom tells me something I didn’t know. “He always felt like we got the life I wanted, not the life he wanted, filled with adventure—diving and sailing,” she says. “He didn’t care about living in a nice house. He cared more about living in other places and exploring.”

“When he talked about buying the boat, I tried to offer him alternatives to make life more exciting,” Mom says. “But he couldn’t be swayed.”

Eventually, they were too far along to turn back. “It felt like the boat was in charge of him,” she says. “I know it wasn’t personal but still, the fact that he went off on this trip felt like I wasn’t enough. Ultimately, the boat won.”

Dad loved us—that’s why he compromised on how he wanted to live. His obsession with the boat and the trip suddenly made sense to me. He wanted to reclaim his life.

In the end, my family can go around and around on what happened and why. We’ll never really know. We can feel guilt, regret, and anger. But we’ll always return to this: maybe Dad wasn’t experienced enough to chase his goal, but he had to try or he’d die wondering, resenting his own life. It’s hard to say that anyone should die this way. But the question remains: If you have a lifelong dream, and time is running out, what would you do?

I’m standing in a single-wide trailer that serves as the office of the Nuevo Vallarta marina. It’s the checkout point for boats departing Mexico in the Nayarit region, 30 minutes north of Puerto Vallarta by car, and the last place Dad docked before setting out to sea.

Under fluorescent lights, I see “Richard Irwin Carr” scribbled across a photocopy of his departure papers and recognize his compact, jaunty handwriting. I know it intimately from birthday cards and school notes and phone messages on our brick-colored kitchen counter.

On May 2, 2017, in the early evening, Dad filled out the line labeled Voyage Plan: “Sail to South Pacific and around world.” It reads like a fantasy, like a little boy trying to catch smoke with his fingers.

I can picture his face, flushed from a combination of pride and embarrassment as he handed the papers back to the clerk. Then he would have stuffed his hands into his jeans pockets.

Ian and I walk down to the spot where he had his boat—A-23, the only unmarked stall in the marina and the one most often used for short-term, transient vessels. I touch the cleat where his rope was last unfurled. I’m sure that the sounds around us are no different than they were on the day he left: children playing at a nearby preschool, a boat being sanded, birds chirping, and the occasional large yacht motoring past the marina to sea.

Being here makes it hard to imagine the drama of Dad’s last hours. I think back to the text he sent for Mother’s Day, nearly two weeks into his crossing. I told him I’d thought of him during Wyatt’s birth, and he said: “Think of me often. I’m an interesting person who loves you as a person as well as my daughter. And I find that gratifying!”

A few days later, Ian and I charter a sailboat from the dock in La Cruz where Dad parked for a month and a half before he headed to Nuevo Vallarta. Palm trees and bougainvillea stand out against the white stucco of the thatch-roofed buildings surrounding the marina. The Sunday craft fair is a fiesta of coconut popsicles, fish tacos, and fresh juices.

The deckhand is a young, thin Mexican man in his twenties named Eddie. He looks like many of the skater boys I went to high school with in L.A., wearing Vans and a chain wallet. He puts on Def Leppard and Weezer as we sail into Banderas Bay. His English is excellent. I explain why I’m in town, and when I mention Celebration he grows quiet.

“I remember your dad,” he says. “Short, with gray hair.” Eddie had helped him rig his sails. Then he says, “I offered to go with him.” Eddie had been looking for work as a paid deckhand.

Dad had hoped to find mates to sail with during parts of his circumnavigation—he once wrote on his blog that the experience would feel incomplete without sharing it—but he was anxious about the laws in the South Pacific. He told my mom that he didn’t want to be financially responsible for his crew, potentially made up of strangers, and any medical needs they might have once they hit the ocean. Being beholden felt too risky to him.

As we sail out toward Cabo Corrientes, I take in the horizon, cupping my hands at my eyes like blinders. I want to imagine what it’s like to see only the edge for days on end. I shake my head at the knowledge that Dad turned down Eddie’s offer. He would probably still be alive.

Back home, people ask if going to Mexico was hard. Maybe I was in denial or just numb, but it wasn’t. Being there made me feel close to Dad. The hardest part was leaving, like I wouldn’t feel his presence again unless I returned for a visit.

The other hardest part is that he’ll never know Wyatt. She’s a risk-taker. My first daughter would sit quietly on the bed or changing table, while my second wants to swan-dive off it. I can see her natural inclination to push things out of the way and investigate everything around her.

A writer I know who has interviewed some of the most daring athletes in the world—people who have both flourished and perished in their edge-of-peril pursuits—told me that, at some point, if we feel the itch in our soul to explore, we have to go. Some will consider Dad’s behavior reckless, arguing that he was underprepared (I can’t argue) and irresponsible (maybe, though he waited until his children were grown before setting off). But to assert that he was wrong to go, my writer friend said, is “to deny a potent ingredient that made him who he was—the joy in him, perhaps.” I agree. Maybe I’m like Dad and I would have gone, too.

At the memorial we held five months after he vanished, a family friend talked about the grudge she felt when he first explained his plan to sail around the world.

“How dare he do what he feels like doing,” she said with a chuckle. She told me that she realized her anger was a manifestation of envy and admiration. She respected his doggedness and willingness to do what most are too frightened to.

Patients from his practice—some who had seen him for more than 30 years—-introduced themselves and told stories about times when their lives would’ve gone south if Dad hadn’t been there. I was meeting them for the first time, but they felt like relatives. Their gratitude for him, and for his unrelenting determination, matched what I felt.

Just like his granddaughter, Dad kept pushing things out of his way to get to the horizon. He had a burning thing inside that inspired him to look over the edge. And for a few days at least, he sailed with abandon, the wind at his back.

Like any adventurer, Dad didn’t know how it would end. He had to sail away to find out.

Ali Carr Troxell (), a former editor at �����ԹϺ���, is the managing editor of the magazine Gear Patrol.