Jim Cantore Is the World’s Most Fearless Meteorologist

When Hurricane Sandy closed in on New York City, the Weather Channel dispatched (who else?) Jim Cantore. Nick Heil tagged along for a wet, wild adventure that quickly became something else—a survival challenge in the darkest hours of a killer storm.

New perk: Easily find new routes and hidden gems, upcoming running events, and more near you. Your weekly Local Running Newsletter has everything you need to lace up! .

On Monday afternoon, October 29, 2012, Jim Cantore, the 49-year-old stormchaser from the , stands on the esplanade in Robert F. Wagner Jr. Park, near Manhattan’s Battery Park City, while his camera team establishes a shot with New York Harbor and the Statue of Liberty framed patriotically in the background. Conditions are whippy and gray. CNN and some other news crews have set up nearby, preparing for the hell that’s about to break loose.

A hundred miles or so out in the Atlantic, the eponymous “Frankenstorm,” the “Nor’easter-cane,” the “Hurriween”—a.k.a. —is bearing down fast and about to bowl over the most populous metropolitan region in North America.

“Right now the water’s here,” Cantore barks into his handheld mic, pointing to the tide lapping a few feet below the concrete walk. “By tonight it’s going to be here!” He reaches up and slaps a lamp post, six feet above the ground. Under his familiar network-branded blue jacket Cantore is wearing a kayaker’s drysuit, the first time he’s gone to such lengths, apparel-wise, in more than 25 years of covering severe weather. “With this wind, in late October, you could go hypothermic instantly,” he says. He’d spent most of the day repeating similar versions of the forecast, with his signature gravitas, while his producer, a bearish, bearded guy named Kip Grosenick, triangulated satellite tie-ins with various NBC affiliates. An investor group led by NBC Universal purchased the Weather Channel in 2008—a smart move. Deadly meteorological events have been on the rise for at least a decade, and so have ratings.

Earlier, fighting through the human tide fleeing the flood zones, I’d made my way downtown to embed with the Weather Channel crew. Cantore intended to report on the storm as it blew through the city, and I’d made the dubious arrangement to hang with him in full gale-force glory. If extreme weather had a celebrity face, Cantore’s bald, chiseled head was it. Urban myth had it that he had invented the now ubiquitous technique of broadcasting from the teeth of a storm, but that’s not quite true. That honor goes to Dan Rather, who, in 1961, was the , a move that launched the legendary newsman’s career. But it’s certainly fair to say that Cantore has come to own the modern stormcasting genre. Since he was first dispatched to Florida to cover Hurricane Andrew in 1991, he has broadcast live from nearly 100 hurricanes, tropical storms, and tornadoes. His routine presence at the scene of so much destruction has garnered him an odd sort of fame, perhaps best characterized by a young couple who approach him in the park for an autograph. “We’re big fans,” says the fellow, “but we’re really bummed you’re here.”

Cantore encounters this all the time. When Hurricane Isaac hit the Gulf Coast two months earlier, store owners boarded up their windows and spray-painted STAY AWAY JIM CANTORE across the plywood. He is called, interchangeably, Dr. Death and Dr. Doom. In 2011, in a nod to these monikers, the Weather Channel produced a commercial starring Cantore in swim trunks, on vacation, arriving at a sunny beach. When the frolicking families realize who he is, they scoop up their chairs, towels, kids, and pets and flee, screaming, while Cantore looks around, shrugs, and plunks down in his beach chair.

It’s funny—sort of. A lot depends on where you live and what you’ve lived through. In just the past two years, severe weather has caused 1,624 fatalities and racked up more than $180 billion in damage in the U.S. alone. It got so hot in Australia in the summer of 2013 that forecasters had to add new colors to their weather maps, illustrating highs up to 129 degrees.

When I arrive at the downtown waterfront around midday to meet Cantore, there is a carnival atmosphere. Hundreds of people mill around the park despite the evacuation order for Zone A, lower Manhattan’s most flood-prone streets. Two buff young men jog shirtless through the crowds. A guy on a jet ski photobombs the news cameras, buzzing back and forth in the harbor and launching big air off the whitecaps.

On a break from a shot, Cantore leans his muscular five-foot-eight-inch frame against a bench and hunches over his phone to check e-mail and . He’s bullish on social media. At last count, Cantore had more than 183,500 followers, and he’s particularly pleased that the Sandy coverage has netted him 20,000 more, pushing his total slightly ahead, for the time being, of his weather-compatriot-cum-social-media-nemesis, Al Roker, who he occasionally fills in for on the Today show.

“Thirty-nine! No way!” Cantore says, examining the glowing screen. I assume he’s referring to barometric pressure or some other vital stat from the . But when he shows me his phone, it’s a picture of Cantore, wearing a pressed white shirt at a recent formal event, posing next to a slender, attractive woman in a sparkly dress.

“No way is she 39,” he says. “Damn!”

Cantore, who has been divorced since 2007, is a guy’s guy, a brawny weather bro, but over the years he’s acquired a large contingent of admiring ladies. It’s that irresistible Yul Brynner sex appeal, perhaps, or the way his Master and Commander baritone can pierce an 80-mile-per-hour gust. One time, he tells me, while he was covering a tropical storm in Florida, two intoxicated young women stood behind the camera and flashed him their breasts. In New York for the past day or so, he’s been the focus of a lot of media-on-media coverage. Earlier in the day, as he was becoming a ubiquitous television presence, posted a Jim Cantore edition of “Fuck, Marry, Kill,” a snarky game that assesses a person’s, well, companionability. The consensus seemed to be that—his exuberance over “Thundersnow!” notwithstanding—he was quite a catch.

Grosenick, his 50-year-old producer, walks up. The rain is pelting at an angle now, and Cantore is bundled in a hooded parka. “Can you do Chris Matthews in 15?”

“Hardball? Sure!”

I ask Grosenick how bad the weather has to become before they bail.

“We’ll stay out as gnarly as it gets,” Grosenick says. “That’s our franchise. In fact, that’s our nickname for him—the Franchise.”

Because Cantore has become a de facto expert on extreme weather, he often finds himself pulled, not always willingly, into conversations about climate change. While many leaders in the environmental movement have seized on the rise of natural disasters as a way to galvanize support for the climate-change movement, Cantore is quick to point out that the connection between climate and weather is trickier and more nuanced. In New York, standing at the waterfront as Sandy approached, he tried to explain this to Chris Matthews, on live TV, in just a few seconds.

“Without getting involved in the big fight over global warming or climate change, what is going on?” Matthews asks, his voice rising to a shout.

“I’ll try and make this as brief as I can, Chris,” Cantore says, the waves frothing in the harbor behind him. “What we’ve seen in the last several days is called high-latitude blocking. The globe is warming, and we’re seeing these high-latitude blocks—it’s just like a traffic jam. That’s starting to have implications on what’s going on with our midlatitude systems: more droughts, more floods, more strange systems like this that we certainly aren’t used to seeing. That’s potentially what’s going on here.”

High-latitude blocks, or what are more commonly called high-pressure blocks, are high-pressure systems that set up over the Arctic. They’re historically unusual in late autumn and winter but have become more frequent in recent decades as average Arctic temperatures have risen dramatically faster than those in temperate zones. The blocks are so named because they impede and reroute storm systems as they roll up the East Coast, as was the case with Sandy. In the days leading up to the storm’s landfall, weather nerds had been freaking out about its anticipated inland track (such systems typically dogleg back out to the Atlantic) and collision with an extratropical cyclone. Also worrisome was the intensity of the low-pressure system, which had hit 940 millibars (the standard unit of atmospheric pressure), .

After Cantore’s segment on Hardball, I pressed him on the topic everyone would be discussing in the wake of the storm. Were the storms a direct result of our reckless stewardship of the planet? Our comeuppance for a profligate lifestyle? A hefty invoice for the environmental remodeling we’ve been embarked on for the past century or two?

“No,” Cantore told me. “We can’t say that global warming caused Katrina or Sandy or any of these storms. But is the frequency and intensity of these systems on the rise because of the warming atmosphere? Yes.”

If that sounds like having it both ways, it could be because, as a self-described climate-change skeptic turned believer, Cantore finds himself in an awkward position. Though he is arguably as experienced as anyone scrutinizing a monkey-wrenched environment, he holds only a B.S. in meteorology. He is not a climate scientist. “At the end of the day, I’m an operational meteorologist,” he says. “I go in and look at the models. I don’t have to make you believe in climate change. I have to tell you there’s going to be more extreme weather, and I have to tell you what the impacts are going to be on you. If I can do that, I’m doing my job.”

Cantore is much more comfortable helping viewers get a clear sense of the impending danger of each storm. And as the Weather Channel’s audience and influence has grown, Cantore and the network are playing an increasingly significant role in helping viewers decide how to prepare, a job typically done by state and local governments. One of the more controversial moments during Sandy came when New York City mayor Michael Bloomberg initially announced that city residents did not need to evacuate flood zones, a statement that Cantore and the rest of the Weather Channel team found distressing. “I am very concerned about Mayor @MikeBloomberg decision on no evacuations. Wondering if a hurricane warning would have changed that,” Cantore tweeted on October 27. The mayor’s position changed quickly, however, and evacuation was ordered the following day.

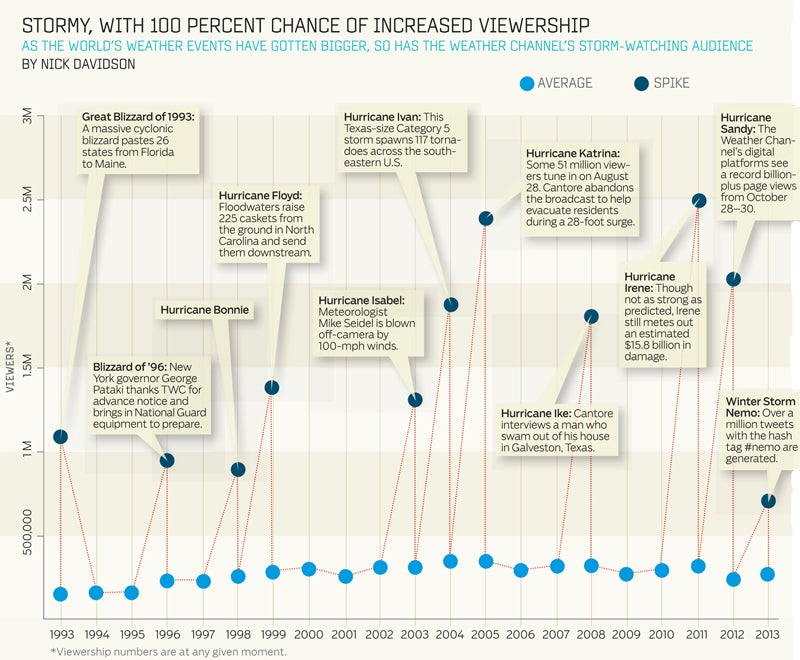

Recently, the network was roundly criticized for naming winter storms, which are trickier to forecast than hurricanes and thus have traditionally been left unnamed by the federally funded National Weather Service. In February the network christened a freak snowstorm heading for the Northeast Nemo and quickly sent Cantore to cover the action. The Weather Channel says , and indeed, #nemo provided a tidy hash tag that garnered more than a million posts on Twitter and a similar volume on Instagram. But it’s also true that storms bring the network huge ratings (see sidebar), and some critics say TWC is ratcheting up our fear of routine weather events in order to profit from our collective panic. “Winter storms are more complex than hurricanes, and their impact is harder to predict,” says Jesse Ferrell, a meteorologist and blogger at AccuWeather. “This seems to be mostly about marketing.”

Cantore isn’t having it. “Numerical weather prediction is one of the greatest inventions of the 20th century,” he told me. “We have super-computers now that can crunch 70 million math formulas a second. That means we can cover the earth with smaller and smaller grids, account for topography, ocean temperature. We can look at really fine detail. My point is that we can , but there’s still a lot we don’t know, and that keeps it exciting. I don’t need to hype the weather. It does a good job of that on its own.”

Cantore joined��the Weather Channel in 1986, back when a forecaster’s sole duty was to stand in front of a green screen and point at an imaginary map. He grew up in White River Junction, Vermont, the oldest of four, in a town of about 2,300 on the New Hampshire state line. It was a quaint, conventional upbringing: high school football and baseball. Springsteen. Loud family dinners over big bowls of pasta.

In early February 1978, when he was 13, a powerful nor’easter rolled across New England. It snowed for 33 hours. When the storm finally cleared out, it left a carpet of snow more than two feet thick from Rhode Island to Maine. “After the plows came through, the roads were like tunnels,” Cantore recalls. “We had this overhanging porch, and my brother Vinnie and I went up to shovel it. By the time we finished, the pile was as high as the roof. We did rock-paper-scissors to see who got to jump into it, and Vinnie won. He jumped and just—ffffmmmtttt!—disappeared. I’m like, ‘Oh, my God!’ So I jump down and I’m digging out my brother, who’s like a foot under. I mean, we could have lost him. That was the storm that got me stoked.”

Cantore attended Lyndon State College, where he studied meteorology. His senior year, he started applying for jobs at various news stations around the country. He looked good on camera and had a flare for bringing wonky science to life. The offers started rolling in—Yakima, Washington; Omaha, Nebraska—but Cantore wanted to stay close to home. “I’m an East Coast kind of guy,” he says. Then, the summer after he graduated, came the call from the Weather Channel. He’s been there ever since.

When TWC launched in 1982, skeptics had doubts that a network dedicated to 24/7 live weather coverage would find an audience. Cantore’s timing was good. By 1987, a year after he started, TWC was piping into 27 million homes, a figure that would climb to more than 100 million—and a startling 89 percent market share across all platforms—by 2012. Even the “weathervator” music, the saccharine soundtrack to the “Local on the 8s” segment, eventually became a hit. When TWC released a 2007 compilation CD, , it soared to number one on Billboard’s contemporary jazz chart. In July 2012, the Weather Company, as the umbrella organization is now called, purchased Weather Underground, a popular site built on a vast community of independent users with home weather stations. The move essentially left the network without a major competitor.

Cantore’s career had a similarly meteoric rise. From the start, he displayed a natural talent for explaining confusing weather events to the masses, especially when reporting live from the field. “What Jim does really well is he takes you there, and couples that with a very scientific mind,” David Kenny, the Weather Company’s chairman and CEO, told me recently. “The reason he’s become a celebrity is that he brings so much authority. Jim can explain what’s going on with a depth you’re not going to get anywhere else. He sets the standard for the whole channel.” In addition to dispatching Cantore to cover disasters, the network has tried to capitalize on his skill set by sending him to report from big NFL games, PGA events, and even a few space shuttle launches. In between it all, Cantore hosts two shows on the Weather Channel, and .

The trajectory of his personal life hasn’t been as perfectly scripted. In 1990, he married Tamra, who worked in ad sales at TWC. They had two kids: Christina, born in 1993, and Ben, born in 1995. In 1998, however, Tamra developed strange and troubling symptoms: sore joints, bodily fatigue, a slight tremor. They received a firm diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease later that year. And the bad news didn’t end there. Ben had been slow to develop as an infant; by age two he still wasn’t talking. Tests revealed that he had fragile X syndrome, the most common known cause of autism. When they tested Christina, doctors discovered that she carried the mutated chromosome as well.

“It was brutal,” Cantore says. “Especially since I travel so much.” He and Tamra divorced nine years later, though the family all live in the Atlanta area and remain close. Cantore often makes public appearances on behalf of Parkinson’s and fragile X.

By the mid-2000s, though his private life was in turmoil, his public persona was becoming a cable TV sensation. He styled himself not just as an expert on the nuances of meteorology, but as its buff and stalwart emcee. “He loves wearing those tight T-shirts,” Al Roker told me. “He’s the Anderson Cooper of weather!” As hurricanes approached, Cantore would ratchet up his gym workouts, as much to look ripped on air as to handle the hours enduring such intense conditions. It wasn’t unusual to see him doing push-ups on camera in the middle of a storm. A video from Hurricane Isaac shows him holding on to Roker, preventing his colleague from being blown down a street in New Orleans. “We had quite the bromance,” Roker laughs now.

In Cantore’s experience, nothing compares to covering the big kahuna of 2005: . He’d been tracking the system since it crossed Florida in late summer, broadcasting from locations on the Gulf Coast. On August 29, the team set up at the Armed Forces Retirement Home in Gulfport, Mississippi, as the hurricane made landfall. It seemed safe enough, perched on a patch of land 20 feet above sea level yet still near the coast. But the surge came in some six hours sooner and several feet higher than predicted, peaking at close to 28 feet. The team’s four vehicles were submerged to their rooftops, and water poured into the first floor of the facility. Cantore abandoned any attempt at a broadcast and instead turned to evacuating residents, some of them confined to wheelchairs, to the second floor.

Everyone in the home survived, but the aftermath scrambled Cantore’s senses. He remembers Gulfport looking like a set from a Michael Bay film, with one exception: it was horrifyingly real. Mud-coated human and animal corpses lay twisted in the rubble. Mature trees had been yanked from the earth and piled up like cordwood. At one point, Cantore saw a sea lion lying in the middle of the highway, miles from its home at the Marine Life Oceanarium.

“Katrina set the bar,” he says. “The smell of death was everywhere. I’ve never experienced anything like it, before or since.”

Events like��Katrina have taught Cantore never to underestimate a storm, and now, late on Monday afternoon, with Sandy’s eye tracking northeast less than 100 miles from central New Jersey, he and Grosenick get ready for another live uplink from the lower Manhattan waterfront. The storm surge in New York Harbor is expected to set an all-time record. Inland, Sandy will collide with a cold front from Canada, dumping several feet of snow from West Virginia to Maine. Cantore is wearing an earpiece and getting updates from Bryan Norcross, the hurricane expert who is coanchoring TWC’s Sandy coverage at the studio in Atlanta. He jots talking points in a reporter’s notebook.

“Man, a hurricane and blizzard warnings,” Cantore says.

“It’s a meteorologist’s wet dream,” chirps Grosenick.

“Yeah,” says Cantore, “but we’re leaving that off camera.”

As the daylight fades, the darkness surrounding us becomes surreal. Con Edison has shut down the power grid in lower Manhattan, and almost all the buildings are blacked out except for generator-powered emergency lights. Cantore and the TWC crew stand inside a bright orb created by their own lights as the surge crests the seawall, creeps over the esplanade, and begins to flood the grass up to their feet. The gusts gain frequency and amplitude, twanging the trees, hitting 70 miles per hour. Somewhat abruptly the wind changes direction and starts barreling directly into New York Harbor. By 9:30 the full force of Sandy is upon us.

Throughout the afternoon and evening, I’d been lulled into a false sense of security by the celeb-gawkers, the autograph seekers, the photobombers, the dude with the circa-1980s VHS camcorder on his shoulder who is walking around documenting the scene, providing his own narration: “See, just like Irene. Oh yeah. Big storm.” But now only a few of us remain, including Cantore, Grosenick, a half-dozen grips, drivers, and cameramen, and TWC publicist Maureen Marshall, an irrepressibly upbeat New Yorker who has been hanging out in the storm long enough that her mirth has finally dwindled. We huddle against the sandblasting gusts while Cantore hooks into another live shot with Norcross. All around the city and across the harbor, power lines are ripped away from poles and transformers detonate at steady intervals, strobing the gray sky with yellow flashes.

“You’ve got power surges everywhere. It looks like a Fourth of July fireworks display over there,” Cantore says into the camera. “Something’s burning! There’s a distinct smell of something that’s burning!”

For the first time in my life, I understand the kind of myopic confusion that seizes those who are caught in natural disasters. Lacking power and with only minimal communications, it’s difficult to understand the scope of what is happening, how long it might last, and what the specific threat might be. Are more slabs of sheet metal on the way, like the one that just Frisbeed past me? Unsure what to do, I duck into a small grove at the edge of the park and tuck up against the trunk of a large tree, maybe 15 inches in diameter. Pressed against it, I can feel the trunk moving back and forth in a rubbery way. Just then, Cantore stomps past on his way to the satellite truck.

“You shouldn’t stand under a tree,” he says, as if everyone knows this essential bit of wisdom.

I deliberate for a few seconds before dashing over to the truck, which is the size of a small RV. Inside, Cantore is on the phone to his daughter, Christina. “Daddy’s fine, honey. I am so proud of you.” Others have packed in, and it’s standing-room only, so I leave to join Grosenick, who is sitting calmly at the wheel of his rental SUV, parked nearby, chowing on a bag of chips and reading and replying to messages on his cell phone. When I ask if this is just another day at the office, he answers pretty much, yes, and then launches into a story about him and Cantore covering , which pummeled Florida in June 2012.

“We’re in the armpit of Florida, and Debby’s coming right at us,” Grosenick says. “The roads get washed out, water just pouring across. We’re trying to make a Nightly News shot, which is a big deal, right? Six million people. I’m white-knuckled, ’cause he always makes me drive. He’s always on the phone. I’d rather drive; when he drives, he’s on his phone anyway. He looks at me and he goes, ‘Are you all right?’ And I’m like, ‘I’m not gonna lie to you. I’m a little scared.’ Eventually, we manage to get the shot out and we’re heroes. But the next day Cantore says, ‘I’m not sure you’re cut out for this job. You need to understand what’s at stake. If we have to break in somewhere and spend the night, that’s what we’re going to do. If we gotta swim for our lives, that’s what we’re going to do. Any. Means. Necessary. When the shit hits the fan and it’s every man for himself and I’m swimming for my life—you better be swimming for your life, too.’ ”

By 11 P.M. the wind lets up, and Cantore comes over to the SUV. They’re done for the night, and he and Grosenick start plotting how to get back to their hotel, which is up by the new World Trade Center building. Problem is, we’re marooned on high ground by floodwater, and it’s not at all clear if we can go anywhere. We start to drive uptown, water sloshing into the wheel wells. There’s a stupefying diesel stench in the air, and the water glistens with an iridescent sheen. A couple of young guys are wading down the street. Cantore thrusts his head out the window and asks if they know of any safe passage.

“Hey, it’s the weather guy!” one says.

“Yeah, hey dude,” says Cantore flatly.

They tell him they don’t know a good way to go. It’s flooded in every direction.

We wend slowly along, violating one-way streets, until at last, around 1 A.M., we reach the Millenium Hilton, next to the World Trade construction site, where a deep pit has filled with water, like a quarry. The hotel’s power is out, but it has rooms available for $400 a night. The clerk is smartly dressed in a gray suit, but his tie and hair are disheveled and he has a vacant look. We check in and he hands us neon green glow sticks to light the way upstairs.

IF, as the saying goes, all weather is local, then the locals just got their asses kicked. In the morning, the hotel is still without power, and the lobby is packed with people charging phones off the ground-floor generator and trying to figure how to get out of the city. The only people who seem to be on their way in stand next to me—a pair of Verizon techs called down from upstate to help get the cell towers back on line. “I worked 9/11, the blackout, Irene, and this is way worse,” one tells me. “It’s so bad, we don’t even know where to start.”

A few hours later, we all meet up at the Battery for Cantore’s day-after coverage. In between live shots, Cantore is summoned to appear on that evening’s Late Show with David Letterman, which is taping at the Ed Sullivan Theater in a few hours. Marshall, the publicist, who lives nearby in Battery Park City, is still sticking it out with us.

“You guys can clean up at our apartment whenever you want,” she says as we drive toward midtown. “I know that’s cold comfort, but if you need a shower…”

“A shower would be nice,” says Grosenick.

“Let’s do one more day without a shower. I like this,” says Cantore.

“Startin’ to enjoy the smell of your own foxhole?” asks Marshall.

Grosenick laughs.

“Wow!” says Cantore.

The Letterman experience is almost as strange as driving into the thriving heart of Manhattan, where, above 33rd Street, the city still looks untouched by the storm. Power, hot food, and New Yorkers abound. We’re ushered in through a backstage door, escorted up a flight of stairs, and shown into a dressing room. Cantore debates his wardrobe: blue jacket or black jacket? He goes with the black one.

After a few minutes, a producer leads him away and we see him appear on the monitor, getting introduced by Letterman. Even the host seems drawn and somber, humbled by the drama of the past 24 hours. He cracks only a single joke: about the storm in Cantore’s bedroom. For the second night in a row, there is no audience because of the weather—the only two times the show has been recorded in a closed theater.

After some topical banter, Letterman asks, “Have the dynamics shifted because of climate change?”

“OK, I knew we’d get there, so let’s go there,” says Cantore. “Every time we’ve looked at an extreme event, this blocking pattern seems to show up. Whether it’s a drought in the U.S. or a heat wave in Russia or a storm that comes north and takes this hook to the left, there’s that block.”

Cantore sets the tone: serious answers for serious questions, and Letterman, a former meteorologist himself, nods understandingly. Meteorologists, in contrast to, say, climatologists, tend to be persons of intractable pragmatism, which helps when it comes to their role as town crier announcing the grave events to come. The larger existential implications are better left to those with the time to afford it. This is, essentially, the meteorologist’s paradox: to announce the weather and yet be confounded by it—to reveal its power, magnificence, and mystery while acknowledging that we are mostly helpless in the face of it.

“How was it?” Cantore asks when he reappears in the dressing room.

“Perfect,” says Marshall. “You looked great. Hit just the right tone.”

“Nailed it, dude,” says Grosenick.

In the following weeks, statistics from the storm coalesce into an unsettling picture: a 900-mile tropical-storm-force windfield, the largest ever recorded, three times the size of Katrina; more than 8.5 million homes without power; upwards of $50 billion in damage; 145 people killed in seven countries, eight of those casualties within a few miles of where we stood when it made landfall.

I catch up with Cantore a few months later. He’d been busy since I’d last seen him, including a ceremonial induction into the Meteorology Hall of Fame in Punxsutawney, Pennsylvania. He was just back from attending the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, with TWC jefe��David Kenny, where international money managers, corporate executives, and policymakers all echoed a familiar refrain: What is going on?

Cantore liked the events—the schmoozing, the glamour, the gorgeous babes—though the travel, exciting as it could be, was taking its toll. For the first time since I’d met him in the fall, he sounded weary. He said that the thing he’d been looking forward to the most in recent weeks was the chance to sneak off to his weekend cabin in the quiet mountains of upstate Georgia, where he and his kids went whenever they could to hike and fish and cook up big bowls of pasta.

But no. Another high-impact weather event was cranking up, and he was being dispatched to Boston in the morning to cover it: Winter Storm Nemo. The pending blizzard had the weather community in a frenzy again. Some models were suggesting it could drop up to 50 inches of snow in parts of Boston (it would turn out to be about half that) and paralyze New England.

“It’s weird. This is the same date that the blizzard of 1978 hit,” Cantore tells me on the phone. “That was my coming-out party; that’s when I realized how much I loved the weather. I remember my dad telling me, ‘You freak out when it snows. There’s something in you that relates to this.’ It just clicked then. He said, ‘You’re going to have to wake up for the next 50 years of your life and love what you do. Think about this.’ And I was like—���Ǵdz�—��DzԱ�.”

Contributing editor wrote about around-the-world-adventurer Erden Eruc in February.