On the Hunt for America’s Last Great Treasure

Millionaire Forrest Fenn launched a thousand trips when he filled a chest with gold, rubies, and diamonds, and hid it somewhere north of Santa Fe. If one man is going to find it, by god, it’s an ex-cop from Seattle named Darrell Seyler.

New perk: Easily find new routes and hidden gems, upcoming running events, and more near you. Your weekly Local Running Newsletter has everything you need to lace up! .

You’re about to read one of the �����ԹϺ��� Classics, a series highlighting the best stories we’ve ever published, along with author interviews, where-are-they-now updates, and other exclusive bonus materials. Get access to all of the �����ԹϺ��� Classics when you sign up for �����ԹϺ���+.

If not for the treasure, it seems unlikely that Forrest Fenn and Darrell Seyler would ever have crossed paths. Fenn is an 85-year-old retired art dealer from Santa Fe; Darrell is a 50-year-old former cop living in Seattle. Fenn grew up exploring Yellowstone National Park; Darrell bounced in and out of foster homes. After a bad tour in Vietnam, Fenn wandered the plateaus and canyons of the desert Southwest; after a divorce, Darrell spent a few unfortunate months on the Dallas club scene—glow sticks, bass drops, put your hands in the air.

Yet the two are inextricably linked by an incredible fact: for the past three years, Darrell has been searching the Rocky Mountains for a chest filled with an estimated million dollars in gold, and Fenn knows where it is. In fact, he put it there.

Fenn has spent his life amassing treasure. As a kid growing up in the 1930s in Temple, Texas, halfway between Dallas and San Antonio, he hunted for arrowheads with his father; he found his first one while walking a creekbed on a drizzly Sunday afternoon. Every summer, his family drove their 1936 Chevy to Yellowstone National Park, where Fenn pulled trout from the streams and scoured the riverbanks looking for agates. By age 13, he was a professional fishing guide in the area. At 16, he read Osborne Russell’s —about the mountain man’s explorations and encounters with Native Americans in the Yellowstone Valley—and set out with a friend to wander the same territory.

“The mountains continue to beckon me,” Fenn wrote in his 2010 memoir, . “They always will.”

In 1950, at age 20, he left the mountains to join the Air Force, eventually flying fighter jets in Vietnam. He was shot down twice, the second time spending a night alone in the jungle hiding from Pathet Lao forces before being rescued.

He was discharged in 1970 and later moved to Santa Fe to start an art gallery, selling paintings, sculptures, and artifacts he’d traded for or found throughout the Four Corners region. His collection, he wrote, “grew to excessive proportions.”

When I met Fenn at his home last September, a museum’s worth of mementos adorned his study: ten Native American headdresses, a wall of moccasins, proof sheets for A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court full of Mark Twain’s own pencil markings. Some are worth a lot of money, others are valuable only for the memories they represent.

“There’s an old saying: ‘I never knew it was the chase I sought and not the quarry,’ ” Fenn says. “Isn’t that a nice little phrase?”

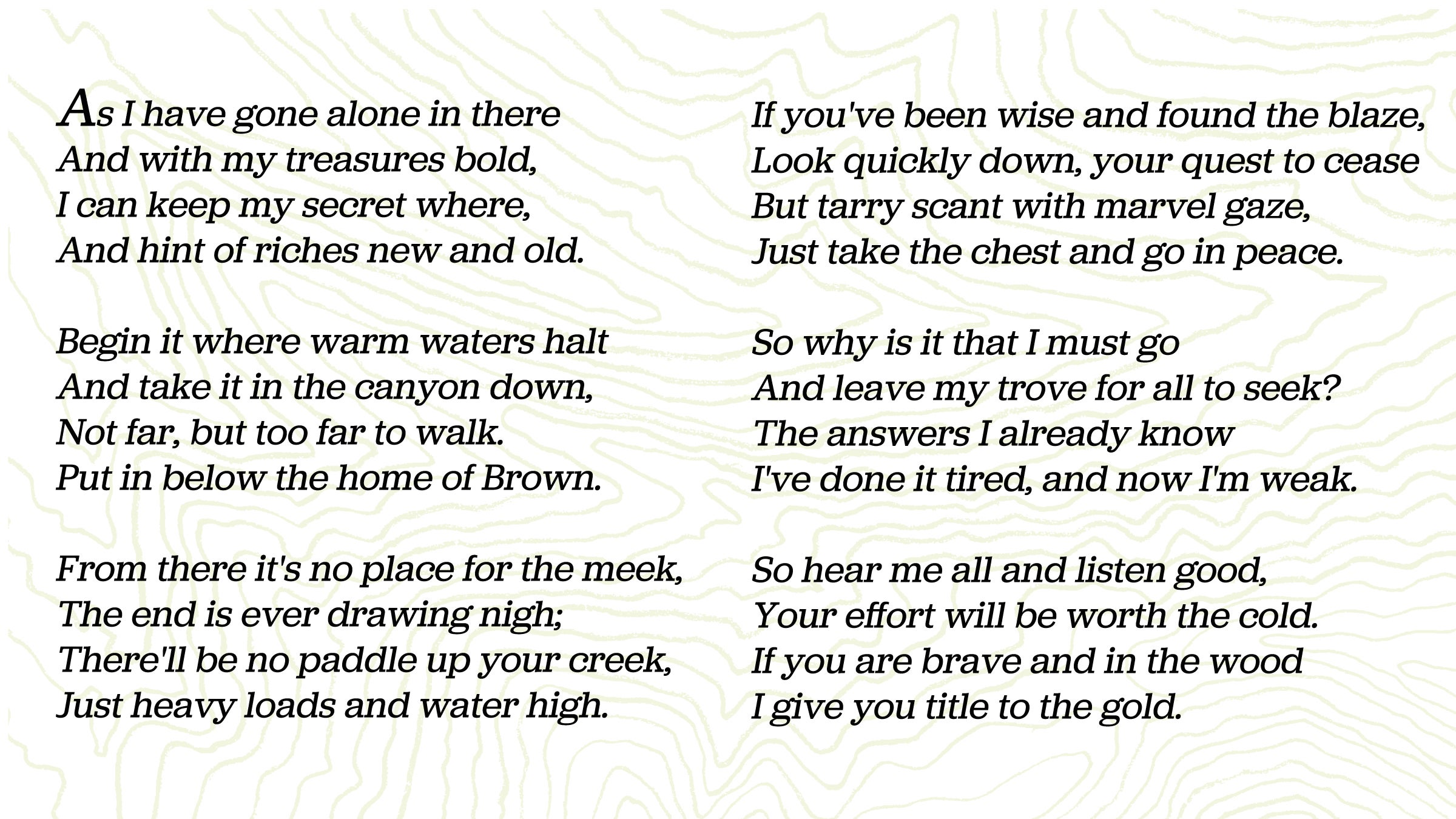

In 1987, Fenn’s father took enough sleeping pills to end a protracted fight with pancreatic cancer. The next year, Fenn was diagnosed with kidney cancer and given a 20 percent chance of surviving three years. He decided he’d go out with a flourish of minor mystery. He’d fill a ten-by-ten-by-five-inch bronze box full of gold coins and jewels, carry it to a final resting place, set it down, and wait to die. The only way to find him—and the treasure—would be to follow the clues he’d leave behind in a poem.

Everything was going according to plan—he’d written the poem and filled the chest with 42 pounds of sapphires, rubies, gold coins, ancient jade carvings, a pre-Columbian gold frog, and a turquoise bracelet—until the cancer went into remission. Fenn put his plan on hold until 2010, when he turned 80 and decided to start it up again. So, like the scores of outlaws and miners whose legends still have shovel-wielding optimists wandering the American West, he stashed his prize. Then he printed the poem in his memoir and waited for the story to spread. There was only one small twist. This time he wouldn’t die next to his treasure; he’d stick around to watch the pursuit.

It’s Thanksgiving weekend, and Darrell and I are speeding east from Seattle toward Wyoming on I-90. When I stopped by his place for the first time, two weeks ago, Darrell said point-blank that he knew where it was. An hour later we were scheming how to get it.

Darrell has soft eyes, angular good looks, and an openhanded demeanor that puts people at ease. Joining us are Harry Greer and George Boyd, friends of Darrell’s who he enlisted to help with the driving. Greer is a craggy-faced ex-con struggling to turn his life around. (“They put a camera on everything these days,” he says.) Boyd has a tendency to wrap conversations back around to how the planets are gods conspiring to provide for him, personally. At least I think that’s what he means. Plan a trip for Thanksgiving and these are the guys who can come along, Darrell says later with a shrug.

Like a lot of searchers, Darrell learned of the Fenn treasure while perusing the Internet on a work break. After a bit of research, he decided that he knew—absolutely knew—where it was: a certain grove of aspen trees in Yellowstone National Park. He had found it on Google Earth, and it lined up with some of Fenn’s clues. He went to retrieve the treasure in January 2013 and discovered that, like every other searcher thus far, he was wrong.

�ճ��������������: Darrell isn’t the only hunter to become obsessed.

But hunting for treasure was like living out his childhood dreams; he’d had Raiders of the Lost Ark on repeat as a kid. He spent most of 2013 dissecting Fenn’s clues and made the 13-hour drive to Yellowstone 17 times between January 2013 and May 2014.

That’s a lot of trips, but Darrell is hardly unique. Fenn estimates that at least 30,000 people have looked for the chest, and searchers range from weekend enthusiasts to semiprofessional hunters to unrepentant fanatics. In 2013 in Tererro, New Mexico, a man was charged with damaging a cultural artifact for digging beneath the white cross of a roadside memorial. Another man dug up graves, even though Fenn has been very careful never to say that he buried the treasure—it’s “hidden.” A woman in Chicago has spent $100,000 on searches she can’t afford. On three separate occasions, hunters have shown up at Fenn’s house acting different brands of crazy, and he has called the police.

“It’s a monster that I created with my story,” Fenn told me.

When I first reached out to Darrell after reading about his hunt online, I wasn’t sure how strong a grip the treasure had on him. But when I drove up from my home in Portland to meet him in Seattle, I found him calm, funny, and willing to bet me all the meals on the drive home that his “solve,” as searchers call it, was correct.

The inside of his place was standard-issue suburban decor: infomercial workout gear on door frames, pinecone-shaped air fresheners, and those vertical blinds that clack together when the heat turns on. He opened his laptop and showed me a picture he took from the bottom of a 50-foot cliff. He was looking at this photo last night and realized that the chest—right there, can you believe it?—was tucked into the rocks halfway up. It’s a spot he’d searched previously, just not the cliff. He talked me through the picture.

“What I thought was, this is the lid, that’s the top, and that’s the latch,” he said. “Can you see that?”

“W�����…�ĝ

“It’s a little difficult at first, I know. How about now?”

He zoomed in so close that all I could see were a bunch of fuzzy squares.

“It’s pretty pixelated,” I said.

But then he talked me through his solution to the first three clues in Fenn’s poem. I thought, Damn, that’s a good solve. Then he talked me through the rest of his evidence and I thought, Holy shit!

Two weeks later, here we are, Greer driving, Boyd riding shotgun, Darrell giving me another tour of the pixelated photographs.

Our plan is to drive 12 hours through the night, get the treasure, and drive right back. We doze in shifts, rotating drivers every two hours. Around 3 A.M., we stop at a Walmart to pick up rope, gloves, and binoculars. The clerk gives us a funny look when we check out—we’re a few full-face stocking caps away from a burglary kit. We also buy snacks and some Montana’s Treasure bottled water. Somehow we forget the binoculars.

Back on the road, the late-November sunrise reveals snow like a hasty coat of primer on the mountains, blond grass showing through. But it’s warmish when Darrell and I don snowshoes and set out to a location I’ve sworn not to reveal. Boyd and Greer, lacking snow gear, stay behind.

I become something of a guide on the three-mile hike, advising Darrell on how to navigate the terrain and lending him some snow pants. When he mistakes a zippered vent for a pocket and loses his phone, timekeeping duties fall to me as well.

Approaching the top of the 50-foot cliff, Darrell says we’ll tie off a rope so he can climb down to the spot. He didn’t bring a climbing harness, however, just a length of fraying cord and the $15 Walmart rope. After watching Darrell tie a knot, I go over and replace it with a real one.

“Look at you, Boy Scout,” he says.

Fenn has repeatedly said that the treasure is “not in a dangerous place.” He hid the chest when he was 80 years old and tells searchers not to look anywhere he couldn’t have gone.

But Fenn is also no ordinary octogenarian, Darrell argues. In fact, it would be exactly like him to let people assume he couldn’t rappel down a cliff. Also, Fenn made his money selling native artifacts from the Southwest. Where did Southwestern cultures hide valuables? On cliffs.

So down Darrell climbs, to the edge of where things turn vertical. But for all his enthusiasm, Darrell is afraid of heights, and that fear speaks to him on a deeper level than treasure. He decides he wants a better rope, better footing. He wants to survey the cliff from down below so he knows where he’s going. The sun is getting low. Let’s come back tomorrow, he says.

We scramble down a much easier route to the bottom. This is the same vantage point from which Darrell’s laptop photo was taken, but to me it just looks like rock.

Beside me, Darrell is having the opposite reaction.

“Oh, oh, oh!” he says. “There it is! I can see it! I can see the brackets he used to keep it in place. He covered it in netting!”

If hunting treasure is a drug, this is the high. Darrell is blissed-out and slack-jawed, tripping over his snowshoes and catching himself without taking his eyes off the cliff.

“Where?” I ask.

“There, there! See the thing that looks like a wheel? Right there! That’s a metal bracket.”

“Darrell, that’s rock.”

We go on like this for a while, debating something 30 feet in front of us like we debated his pixelated photos. If only we’d remembered the binoculars, Darrell says, I’d be able to see what he’s seeing. But we’re past our turnaround time, so he has me take some pictures with my phone, we walk back to the car, and we drive an hour to a Super 8 motel.

Darrell is adamant throughout the drive that what he saw is the treasure. He’s zooming in on my phone, explaining how the chest is on a ledge that we couldn’t see looking up from below. But, he says, you can see a fuzzy image of it projected onto the rock above the ledge. Cameras will do that. The light bends. You can only see it with a camera.

“Darrell, when I look at these pictures and I can’t see what you’re seeing, do I sound crazy to you?” I ask.

“No,” he says. “And I don’t think I sound crazy, either.”

Like something out of an airport mystery novel, Fenn’s poem is a rhyming literary treasure map: six stanzas, nine sequential clues, all as vague as a jigsaw puzzle strewn across the table. The key to solving it, most searchers agree, is figuring out the line “Begin it where warm waters halt.” From there you’re looking for a “canyon down,” and then some sort of “home of Brown.” Find all three in succession and maybe you’re in business. �����ԹϺ��� of that, there’s hardly a consensus as to which lines are real clues.

Subsequent information from Fenn has narrowed the search area to elevations between 5,000 and 10,200 feet in Montana, Wyoming, Colorado, and anywhere north of Santa Fe in New Mexico, but those states are chock-full of hot springs, warmish lakes, warm-water reservoirs, canyons, brown trout, brown bears, and ranches and mountains named for one Brown or another, so it’s hard to get much more zeroed-in than that.

Dal Neitzel, a searcher from Lummi Island, Washington, who , has gone looking for it more than 50 times. A longtime underwater treasure hunter, Neitzel first heard of Fenn while searching for a sunken ship in Uruguay with Forrest’s nephew, Crayton Fenn, who told story after story about his madcap uncle.

A few years later, back on dry land, Neitzel Googled Forrest to see what he was up to. Top results: hiding treasure and writing poetry.

“I thought, This is going to be simple!” Neitzel said. “I’ve found lots of stuff with no directions. If this guy is going to give me some, this will be easy.”

That was five years ago.

Fenn once wrote that most searchers overcomplicate the clues, resting their solve on obscure knowledge or hidden codes—bending the poem to fit their solution rather than the other way around.

Despite Fenn’s insistence that searchers focus on the text, nothing seems off-limits. There are as many solutions to the poem as there are nooks and crannies in the Rocky Mountains. For example, if you start at Flaming Gorge Reservoir in Wyoming (where warm waters halt) and continue downstream 15 miles (too far to walk), you come to a park named for French Canadian fur trapper Baptiste Brown (home of Brown). Follow the river and you come to Fort Misery, where pioneer Joseph Meek hid out among notorious outlaws (no place for the meek). The geography, the trappers, and the wordplay all read like classic Fenn. But: no treasure.

Darrell’s current solution doesn’t rely on obscure facts, and it dovetails in a really elegant way with some things Fenn has said about the hunt. Go online and you’ll find folks parsing Fenn’s every word for hidden meaning and contradictions. The level of scrutiny is formidable—some searchers have gone so far as to compile all of Fenn’s published spelling errors looking for patterns—but it’s also a reminder of just how much collective brainpower is going into solving this thing.

In other words, Fenn’s poem isn’t just a riddle. It’s also a race.

The next morning, our plan is the same. Hike in, get the treasure, and cannonball home. Except this time Harry Greer comes with us. He’s never been snowshoeing before, and he’s been commenting the whole trip about how amazing the landscape is. He also wants to earn the money Darrell promised him, so he volunteers to be the one who rappels down the cliff. I offer to make him a cheap harness, but no one wants to stop to buy the webbing we’d need. Instead, when we get to the spot, Greer wraps the rope around his chest four times and edges toward the cliff. If all goes well, he’s thinking, the friction will feed the rope out slowly as he drops to the bottom.

“Are you comfortable with this?” I ask.

“No,” he says, dropping over the ledge. “But I’ve got a lot of bills to pay.”

Of course, the rope-corset crushes his chest immediately. As he continues to lower himself, I track his progress via grunts of pain echoing through the wood.

Darrell is below, dodging falling rocks and excitedly guiding him to the treasure.

“Check up there, yeah, to the left, on that ledge. OK, yeah, hold on. You can take a minute,” says Darrell.

“It’s not here, boss.”

“Check on that ledge. Over there. Can you see it? Dig around a little bit. It’s there.”

Greer gets a knife out and scrapes it along every flat surface. He looks down at Darrell, who is waiting like a puppy for a treat, and then searches everything again. “Nothing but rock. I’m sorry.”

This does not sit well with Darrell; for him, this treasure isn’t just treasure. It’s redemption.

Darrell grew up outside Seattle, where his drug-addicted mom occasionally worked as a prostitute. He was, he says, “the result of a John in an alley somewhere.” The only black kid in his white mother’s family, he had seven stepfathers over the years. None liked him much.

Very early he decided he would become a cop—the guy coming to the rescue—and that goal kept him improbably devoted to the straight and narrow. In 1991, after serving three years in the Army’s military police, Darrell joined the King County sheriff’s office. “Every day was my birthday,” he said, describing the job and its steady paycheck.

Then, in 1997, Darrell was pursuing a suspect on foot and slashed the guy’s car tires so that he couldn’t circle back and drive off. But the car was registered to someone else, they filed a complaint, and the department let him go. The fuck-up cost him a job he loved; the stress cost him his marriage.

When his ex-wife started appearing on Seattle billboards—she’d won a bikini contest—he fled to Dallas, partied his divorce away, and started dating a Dallas Cowboys cheerleader. But he landed back in Seattle a few years later when he got tired of the lifestyle. He worked for a couple of mortgage companies, then took a desk job recruiting engineers for B/E Aerospace in 2011. He was good at it, and his life stabilized—until the treasure popped up on his computer screen.

“I would leave on a Friday, right after work, have my vehicle packed and ready to go, and I’d get back from Yellowstone, without any sleep the entire weekend, at 8 A.M. on Monday,” he said.

Soon that schedule encroached on his job performance. A couple of times he didn’t show up on Monday until noon and got written up. His friends told him to quit the hunt.

It all came to a head in April 2014, when he drove to Yellowstone with a friend and flipped his raft trying to cross the Lamar River. He was washed 1.5 miles downstream, nearly drowned, and spent a 26-degree night soaking wet on the river’s snowy banks before search and rescue got there. But then, instead of waiting to see which of the 16 misdemeanors and park violations local prosecutors were going to pursue, Darrell drove back to Yellowstone in May, crossed the Lamar on foot, lost track of time, spent another night on the riverbank, and was again picked up by search and rescue.

Things spiraled quickly after that. The park charged him with reckless endangerment, illegal camping, and possession of a metal detector in the backcountry. He spent six days in the Bighorn County Jail in Montana, and in a plea agreement he was ordered to pay a $6,000 fine in monthly installments. He lost his job, got kicked out of his apartment, and spent two months living in his car. Eventually, he fell behind on the fine payments, and a warrant was issued for his arrest. All the while, he kept hunting for the treasure on McDonald’s Wi-Fi.

Fenn made his money selling native artifacts from the Southwest. Where did Southwestern cultures hide valuables? On cliffs.

So, more than money, this treasure is a culminating triumph, a chance for Darrell to become the man he once was. And when it’s not here, where he was absolutely sure it would be—where he had seen it in a photo!—Darrell loses it. He kicks a tree in anger, doubles over, and clutches his head. When Greer comes down, Darrell takes the rope to check the spot himself. We wait at the bottom, but after 15 minutes there’s no sign of him, and I go looking. Eventually, I find him slumped against a rock, the rope tangled in his snowshoes, crying.

This was his last idea. He’s running out of money.

“Is this the end?” I ask.

“Yeah,” he says. “Of a lot of things.”

It’s tempting sometimes to think that there is no treasure; that a puckish old man is having a laugh at everyone’s expense. Even veteran searchers say they sometimes waver on that point.

But Fenn is more interested in experience than irony. He once published his phone number in a newspaper telling people to call and wish his wife happy birthday. Besides, his family’s inheritances are set, and he says failure is dying with more than $50 in your bank account.

Some speculate that Fenn designed this whole thing to get people digging around on federal lands as a kind of middle finger to government agencies that have long thought he’d bought and sold illegally obtained relics. In 2009, the Bureau of Land Management searched his house in a sting targeting the Native American artifacts trade in the Four Corners region, but the U.S. Attorney agreed to drop the case if Fenn would return a kachina-dance mask, a basket, and a sun-dance skull, and agree not to sue them for falsifying the warrant.

Weigh out the factors for and against the treasure’s existence and you’re left with the question: Would Fenn really make this whole thing up?

The best place to get a sense of Fenn’s personality is in , a section of Dal Neitzel’s site where Fenn blogs regularly. The scrapbook mostly consists of Fenn’s thoughts and stories, but occasionally it offers real insights and even outright hints. addresses the clue “where warm waters halt,” which many had thought referred to warm water collecting in a reservoir, like at Flaming Gorge in Wyoming.

“I have discussed around that subject with several people in the last few days and am concerned that not all searchers are aware of what has been said,” he wrote. “So to level the playing field to give everyone an equal chance I will say now that WWWH [where warm waters halt] is not related to any dam.”

To dedicated searchers, this kind of solid fact slakes a terrible thirst. While there are other blogs, like and , Forrest’s Scrapbook is everyone’s favorite watering hole. It gets roughly 8,000 visitors a day, but only a hundred or so searchers comment regularly—it’s where Darrell and Neitzel and others congregate and converse. Though it’s a supportive group, not everyone is completely forthcoming.

“I don’t think there’s a lot of malicious misinformation,” Neitzel told me about the conversations. “But I do think there’s some redirection.” If it seems like someone’s getting close, he says, someone else might volunteer a thought just to throw the other hunter off the trail.

In June 2014—a month after his arrest in Yellowstone—Darrell e-mailed a group of five sisters from Florida and Georgia who had been and were active on the blog. One of them—Melani Ivey—shared Darrell’s dedication to the hunt, and the two soon started e-mailing and talking on the phone, feeding each other’s enthusiasm.

“It’s like a black hole,” says Ivey, 43, who lives in Panama City, Florida. “The more you read, the more you want. You never stop.”

When Ivey’s sisters took her on her first hunt, also in Yellowstone, a moose charged them. That bit of adventure hooked her. “It was the time of my life,” she said. “From there forward, I haven’t put it out of my mind.”

She and Darrell could spend hours on the phone dissecting clues without noticing the time. It was only looking back that she started to see pieces of her life going missing.

“I loved to hike,” Ivey said. “After searching I thought, Great, now I’m not even going to enjoy a hike, because I don’t have a treasure to look for.”

She tries to give up the hunt every so often but always gets pulled back in by her sisters or Darrell or a new idea.

“You want to live in that fantasy world,” she said. “You want to believe that there’s a treasure out there that’s going to solve all your problems.”

For Darrell, Ivey is a crucial support system. She understands the pull, what he’s going through, the God-that’s-good excitement of solving a clue. Which is to say that she’s not very helpful when it comes time to quit.

I didn’t expect to hear from Darrell for a while after our unsuccessful hunt. On the drive home, he told me that I could start searching his spot if I wanted. He was done: no more blog, no more poem.

Then, one morning a few weeks later, I get several e-mails in a row, then a text to let me know that he sent an e-mail. A few hours later he calls. He’s back on the hunt.

We start planning a trip to the very same cliff for the day after Christmas, just the two of us. Darrell will be done with a contract job by then—he has yet to find full-time work, but he’s making do—and he wants to search it himself, because Greer didn’t really know what he was looking for and the climbing rope had treated him like a spent tube of toothpaste. Bronze develops a green patina when exposed to the elements, Darrell says. Maybe Greer missed it. It’s worth going back with real climbing gear.

His e-mails contain photos of the cliff with circles highlighting some faint mark or symbol. He’s seeing images in the rock—a letter F, some sort of fish, faint white numbers, maybe petroglyphs Fenn left behind—and he wants to know if I can see them, too.

Sometimes I can, but it’s like seeing things in clouds.

When Darrell sends the photos to Ivey, she backs him completely and tells him to get on the road. When he sends them to Neitzel, he offers to go take a look if Darrell will divulge his secret spot. And when he sends them to Fenn, the reply sends Darrell into a frenzy.

Well, Fenn doesn’t respond directly to Darrell; but he does post on Dal Neitzel’s site the very next day. It’s Scrapbook , posted December 15, 2014, and consists of pictures of the marble in Fenn’s shower. Each photo caption explains something he sees in the swirl of rock. There’s a cowgirl, a dog, some Gollum-looking critter.

To most, it’s a cheeky glimpse behind the curtain—a little weird, even for Fenn, but not unheard of. To Darrell, it’s confirmation.

So: same drive, same Walmart, same snacks, same Montana’s Treasure bottled water, same failure to get binoculars when the cashier informs Darrell that the charge would overdraft his account. He has less than $50 in it.

It’s six below zero when we get to the spot, and a breath of wind drops it another few degrees. Clouds drift by low and thick; the sun is just a moldy peach on the horizon.

It takes forever to get into our climbing harnesses and set up the rope I brought. When we’re finally ready, Darrell doesn’t trust the knots. He clambers down past the canyon edge, then freaks out, grabs the rock, and climbs back up the cliff, wrapping the rope around his arm as he goes.

I offer to rappel down first to show him it’s safe. I can even search the cliff if he wants.

“You would do that?” he asks.

I do that. Darrell tells me where to go, and I scramble around on the rope and look. No treasure.

When I get to the bottom, Darrell is bent over in pain. His toes were frostbitten years ago during basic training, and when they get cold it’s unbearable. We duck out of the wind to warm up, and he tries to rub some life back into them. It’s like listening to someone stub his toe for 15 minutes. He’s only wearing one pair of cotton socks, and his boots are too tight. He has no feeling in one foot. We’re going to have to come back tomorrow.

Same Super 8 motel. Darrell rolls onto the bed still wearing his snow pants and jacket, and he wraps himself up in the bedspread with both arms. He says he’s fine, he’s not sinking into one of his post-hunt depressions, but he doesn’t want to talk, just watch TV. Indiana Jones is on, but it’s the new, crappy one with Shia LaBeouf. Soon Darrell falls asleep, still in his clothes.

The next morning, I get up at 7 A.M. and sort wet gear from dry, but Darrell hits snooze a couple of times. He finally goes down to the hotel lobby for breakfast, but then collapses back onto the bed.

It’s like he’s lost a part of his mind, he says. He’s not sure if he’s acting rationally or logically anymore. He might want to quit—really quit—the hunt.

“Where has it gotten me?” he says. “I’m in a motel room I can’t afford, and I look like a crazy person seeing things in walls that aren’t there.”

He says he wants to go back to the spot to rappel down that cliff, but more to prove that he can do it than to find the treasure. But can he even trust that feeling? Should he make sure he didn’t miss anything? Will that quell his desire to come back later? What will he do with himself if he’s not out searching? This has been his life for two years. He’s facing away from me, talking into his hands, curling into a ball. Withering.

When you’re as deep into this thing as Darrell is, the only way to know you’re on the right track is to find the chest; there’s no incremental success. You’re either all-in or you quit. But he can’t quit. He must be close.

After all, why did Forrest post pictures of his bathroom and write about the things he was seeing in the marble? Where do warm waters halt? Who is Brown?

Snow whips past the window in a silent blur. Darrell sits on the edge of the bed, searching for himself.

Peter Frick-Wright lives in Portland, Oregon. This is his first feature for �����ԹϺ���.