Fact #1:��.

Fact #2:��Your odds of being injured by a bear while carrying a firearm are the same as if you’re carrying no defense at all.

I’ve always taken the scientific studies that arrived at those two conclusions as gospel. And I’ve��written articles repeating their findings while arriving at the invariable conclusion that bear spray is better than a firearm when it comes to defending��against a bear attack. But you know what? I was wrong.

“There was no thought of comparing the two [studies], though some do that,” says Tom Smith, who authored��both reports, titled��the “Efficacy of Bear Deterrent Spray in Alaska”��and “.”

Yet many people—including me, obviously—have compared the results of those two studies. And that, according to Smith, was never his intention.

Entirely Different Methodologies

Read beyond the results of the two studies and you’ll see that, despite similarities in subject matter and titles, they actually cover two very different scenarios.

The bear-spray study includes 83 incidents spanning��from 1985 to 2006 in which the deterrent was employed. Of those incidents, 50 involved brown bears—on 31 occasions, the bear was curious��or seeking food, while the remaining 18 cases involved an aggressive bear. There were only nine studied instances where a brown bear charged a human.

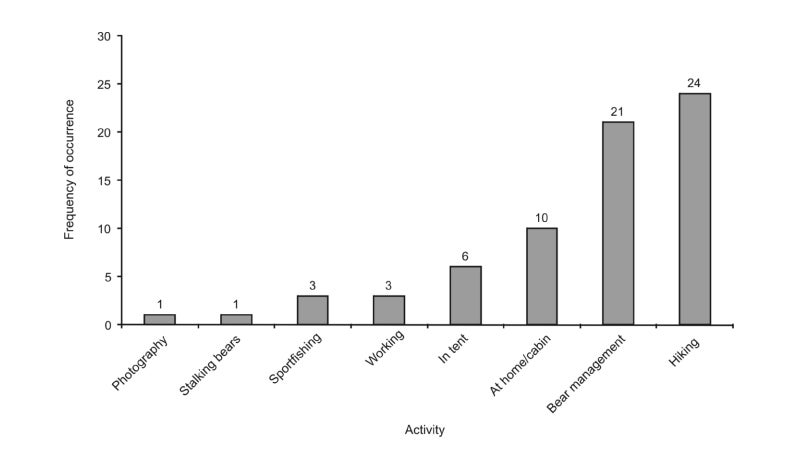

Twenty-four of the people��in the bear-spray study were hiking when they encountered a bear. Twenty-one��were wildlife officials engaged in bear management. The rest��were doing a variety of the usual outdoor activities, including��photography and��fishing. None were hunting.

I asked Smith to clarify the nature of bear-management incidents in which bear spray was used. Was the use of the spray premeditated and intended to alter the behavior of the bears involved? “These were largely intentional hazings, not surprise-encounter-type situations,” he says.

In contrast, the firearms study��“compiled information on bear attacks,” with 269 incidents between��1883 and��2009 selected, notably excluding Alaska’s own Defense of Life and Property (DLP) records, . Smith and his coauthors acknowledge the effect this exclusion had on the study’s findings, writing:��“Because bear-inflicted injuries are closely covered by the media, we likely did not miss many records where people were injured…. if more��incidents had been made available through the Alaska DLP database, we anticipate that these would have contributed few, if any, additional human injuries.” The study states that including that data would have improved the reported success rates for firearms.

I asked Smith to explain why the DLP records were excluded from his firearms��study, when they seem to so obviously represent a large amount of data��on firearms efficacy. “All of the records cited in Miller’s paper were missing from the files, as though they had never been returned after they completed their analysis,”��he explains, also noting that state officials denied him access to more recent records, due to privacy concerns. Does Smith think the results would have been different had he gained access to the DLP data? “The main value isn’t in the percentages reported but in taking a look at why firearms failed to protect people,”��he says. The point of “Efficacy of Firearms”��wasn’t to arrive at a conclusion on whether or not firearms work but, rather, to analyze the reasons why they didn’t—“poor aim, no time to use them, jammed, etc.,”��elaborates Smith.

“Comparing the two studies is like comparing the injury rate for people picking up apples to the injury rate for people picking up live hand grenades,” says Dave Smith, a naturalist who has worked in Yellowstone, Glacier, Denali, and Glacier Bay National Parks��and who has on surviving dangerous encounters with wildlife. It makes no sense to compare��bear encounters where bear spray was employed with actual bear attacks, he says. There’s another flaw in the data:��incidents in which��users were unable to access their bear spray in time were excluded from samples, while users who experienced malfunctions with, or were otherwise unable to employ, their firearms were included, since that was the point of that study.

Like-for-Like Results

Diving into Tom Smith’s two studies, we can uncover some data similar enough to merit a limited comparison.

The bear-spray study looked at��14��close encounters with aggressive brown bears. Of those, the spray was successful at stopping the bear’s aggressive behavior in 12 incidents. The firearms study��found that 31 of 37 handgun users were successful at defending themselves from an aggressive bear attack. That’s an 85��percent success rate for bear spray, and 84 percent for handguns.

The bear-spray research included nine brown bear charges where the spray was successful at stopping the charge three times. Alaska’s DLP reports (which primarily involve firearms) from��1986 to 1996 include data on 218 brown bear charges. Those same reports put total human injuries caused by brown bears in DLP incidents at eight, plus two human deaths. If we assume that all ten of those injuries or deaths were a part of those 218 charges (an unlikely but worst-case scenario), then the success rate it finds for firearms in brown bear charges is over 95 percent.

I asked Tom Smith if it was valid to conclude that the studied effectiveness of bear spray in brown bear charges is just 33 percent. “That’s what you would conclude from that data,” he says, before going on to point out that the sample size is very small. “Importantly, protracted mauling did not occur,” he says.��“Whether that’s due to the spray or simply due to the vagaries of bear attacks is an open question.”

The Trouble with��Numbers

Thirty-three percent is very far from that 98 percent efficacy rate . And it’s an especially problematic number if we accept that firearms can be demonstrated to have a success rate of between a 76 percent (in a worst-case scenario, as presented in “Efficacy of Firearms”) and��96 percent (as is the case in Alaska’s DLP data��or ).

Conflating the results of Tom Smith’s two studies has��informed everything from ��to , and more importantly, the resulting conclusion��guides bear-attack survival advice that’s , , and . If the��conclusion that bear spray is more effective than firearms is wrong, then the entire way in which we’ve approached coexisting with the brown bear is also wrong.

Does Bear Spray Work?

So is it? I think it just presents a more limited conclusion than the one we’ve all chosen to believe, leading to an unfortunately narrow understanding of our relationship with bears.��“The appearance that bear spray outperforms firearms was not the focus of our work,” says Tom Smith. “We wanted simply to highlight the pros and cons of each and let individuals decide how they best could stay safe in bear country.”

While “Efficacy of Bear Deterrent Spray”��sends a mixed message on the effectiveness of bear spray in aggressive brown bear encounters—and a very bad message about its usefulness during a brown bear charge—it does show that the spray is enormously effective at deterring brown bears when they’re simply curious. Of note here is the conclusion in “Efficacy of Firearms”��that��“No bears were killed when firearms were not used.” Bear spray gives users a nonlethal way to influence the behavior of a brown bear before it risks human life.

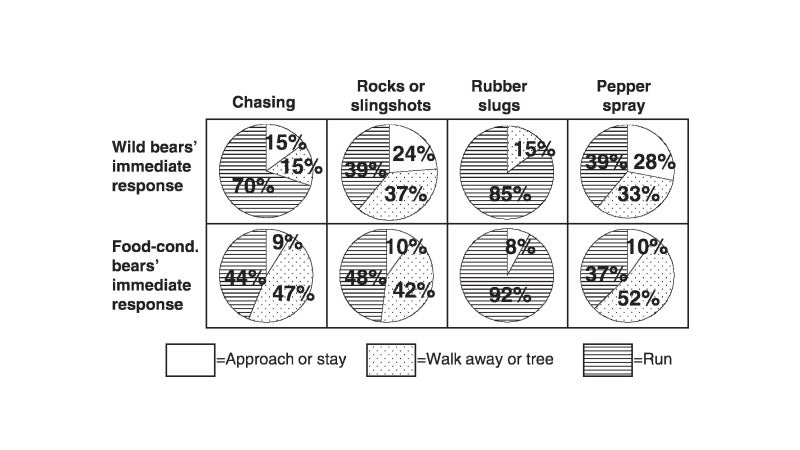

You’ll note throughout this article my careful delineation of results by bear species. That’s because the bear spray’s efficacy was largely studied on brown bears; results on polar bears are largely from use in hazing, while another study found that bear spray isn’t terribly effective on black bears. The 2010 study “”��found that methods like chasing, rock throwing, or shooting black bears with nonlethal rubber shotgun slugs were as effective as, if not more effective than, pepper spray. Conversely, Tom Smith has demonstrated elsewhere that polar bears, often feared as human predators, are the least likely of all three species to .

What We Don’t Know Can Hurt Us

In 1998, researchers at the University of Calgary, in Canada, published “.”��It analyzed 66 field uses of bear spray between 1984 and 1994 and found that, in 15 of 16 close encounters with aggressive brown bears, bear spray was effective in stopping the bear’s unwanted behavior—a 94 percent success rate. But��read closer, and it’s apparent that in six of those cases, the bear hung around and continued��to act aggressively. In three of those 16 close encounters, the bear attacked the human after being sprayed, despite receiving what the study refers to as, “a substantial dose of spray to the face.” Interpret this data differently, and in a worst-case scenario, the demonstrated effectiveness occurs in seven��of the 16 incidents—a 44 percent success rate. This study did not compare these results either to the efficacy of firearms��or with no defense method at all. The study did find that the spray was effective in 20 of 20 encounters with curious bears.

The bottom line is that no study has ever��attempted to compare the effectiveness of bear spray to that of firearms. All studies are limited both by the outright rarity of bear attacks and the inability to recreate them in a controlled environment. We’re parsing an incredibly small number of encounters influenced by a huge number of variables, then trying to arrive at definitive conclusions. The best we can do is compare disparate data sets, applying our own subjective criteria to try and arrive at an inadequate conclusion.

Yet in , , and , we have an��overwhelming impression that bear spray is the one-stop solution to safely recreating in bear country. Dave Smith calls this, “propaganda” and says he fears that it leads to misinformation and misunderstanding about what it takes to stay safe around bears.

Tom Smith states, again, that he would not compare the two studies—“Efficacy of Firearms” and “Efficacy of Bear Deterrent Spray”—directly. Yet a , where he works as an associate professor, did conflate results from the two studies, leading to stories in media outlets like that conclude��“A rifle apparently doesn’t work as well as a canister of red pepper spray.”

We Need Data-Based��Bear-Safety Guidelines

My entire purpose for writing this article is to illustrate that the exaggerated effectiveness of bear spray is getting in the way of more important advice on bear safety. Here in Bozeman, Montana, just north of Yellowstone,��it’s common to see people being told to carry bear spray any time they go on a hike, but almost always, the advice stops there. And��while the spray may be effective at deterring a curious bear, it cannot be shown to have the ability to effectively stop an actual bear attack. Something more is needed.

Is that something more a firearm? “If you’re competent, then a firearm is a valuable, time-tested deterrent,” says Tom Smith. He goes on to reference the case of Todd Orr, who was famously mauled twice by the same bear here back in 2016. Despite employing the spray, the bear still managed to attack Orr, then later stalked and attacked him again. “Bears accurately shot don’t have that option,” says Smith. “Game over.”

But user competency is the largest determining factor in the successful use of a firearm. “When a person is competent with firearms—and I mean competent under pressure—it is an effective deterrent I highly recommend,” he says. “Conversely, those with little to no firearm experience shouldn’t rely on a firearm to save them from a close encounter with a bear.”

He recommends . “However, even that same firearm-competent person would do well to carry bear spray also,” the researcher states. Smith highlights bear spray’s��ease of use��and portability as the reasons for that, as well as its effectiveness in nonlethal encounters.

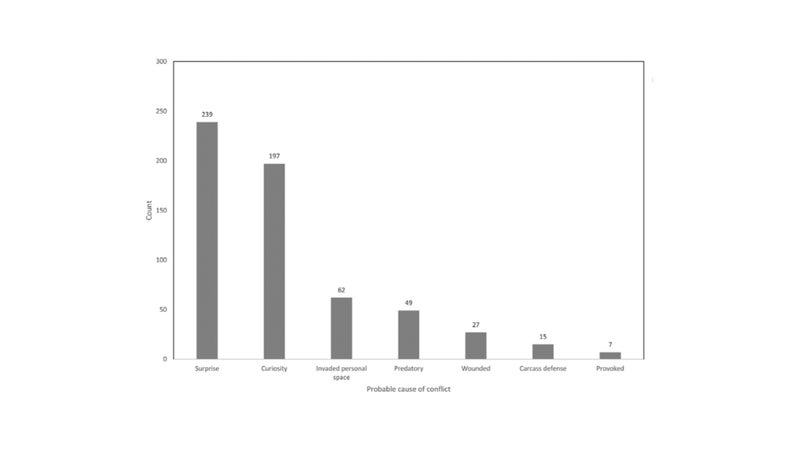

But any talk of bear spray or firearms tends to get in the way of advice on how to avoid conflict with bears in the first place. It’s Smith’s 2018 study “”��that comes to the most effective, actionable��conclusions. It looks at��the human variables involved in��bear attacks, and from those��we can glean some truly eye-opening information.

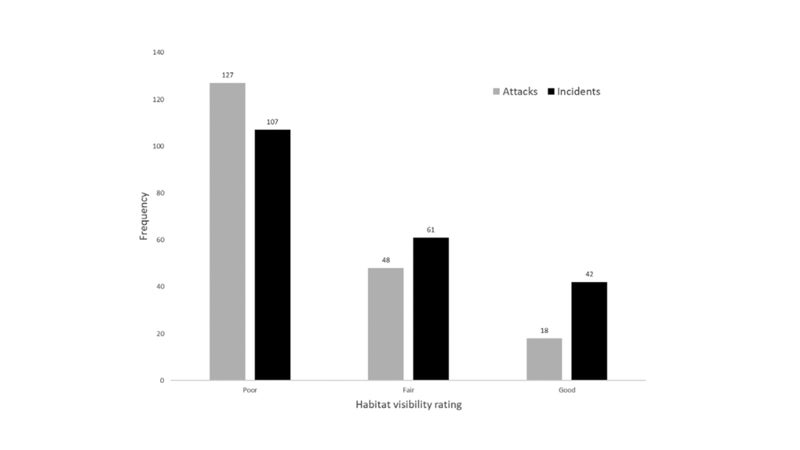

That study found that the kind of habitat in which you encounter a bear is a major determining factor on the likelihood of an attack. “The poorer the visibility, the more likely bears were to engage with people, presumably because of an inability to detect them until very close,” it states. It also notes that human rescuers had a success rate of over 90 percent at terminating maulings and were only mauled themselves in less than 10 percent of those rescues.

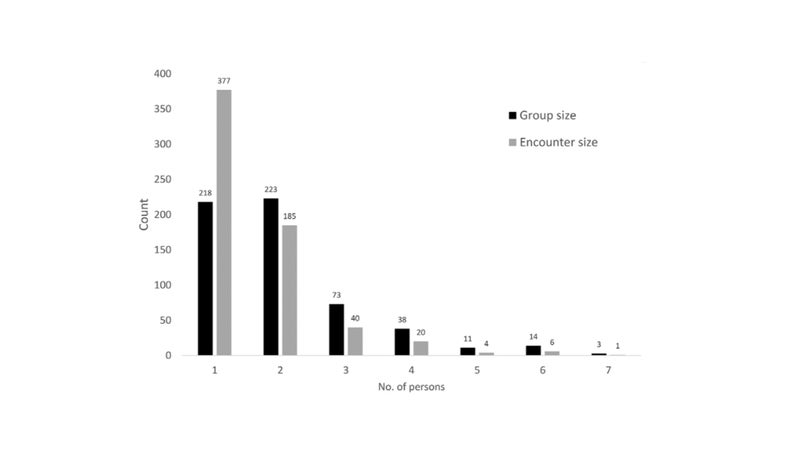

There’s one more surprisingly effective piece of advice that comes from the 2018��study: travel in groups. “The larger the group, the less likely to be involved in a confrontation,” it finds.

“To the best of my knowledge, I have not seen an instance where two or more persons have remained grouped, whether standing their ground or backing from a bear,��that the bear made contact,” says��Tom Smith. “That seems an important piece of advice.”

So what’s the conclusion��here? To me, this isn’t an argument for or against guns or for or against bear spray. It’s an argument that, despite the presence of deterrents, dealing with an aggressive bear encounter does not involve any sure outcomes. Rather than beginning and ending the conversation with a false statement about bear spray’s efficacy, we should instead acknowledge that recreating safely in bear country requires training and knowledge—not dogma.