On Tuesday, April 23, basketball player was given the , an honor issued by the Amateur Athletics Union (AAU) to the best amateur American athlete at the collegiate or Olympic level. The AAU is a youth sports league juggernaut with 800,000-plus members, aligned behind the soaring motto, “Sports for All, Forever.” Clark, 22, is a worthy recipient of the winner’s statuette—her second win in as many years—after vaulting women’s collegiate basketball to stratospheric popularity and media attention during her run to the NCAA finals with the University of Iowa.

“The AAU Sullivan Award is an incredible honor,” Clark said. “I have been inspired by so many athletes that came before me and I hope I can be that same inspiration for the next generation to follow their dreams.”

But Clark’s records and her passion for inspiring young women athletes isn’t at all what the award’s namesake, James Edward Sullivan, had in mind. Sullivan, who founded the AAU in 1888 and died in 1914, was dead set against women competing in sports. In fact, Sullivan’s actions and writing presented opinions on race, gender, and equality contradicting the stated “Sports for All” mission and the essence of the modern AAU, which has for years sought to better identity and celebrate diverse athletes.

“Right here rests the salvation or ruins of athletics in this country,” Sullivan said in a 1914 interview in Los Angeles’ Mercury magazine. “Women have little or no place in athletics.” Later in the same article, Sullivan was more specific in expressing his sexism. He was set to direct the upcoming 1915 Panama-Pacific Exposition, which was billed as the biggest athletic event ever in the U.S. “You can take it from me that women will not figure in the Panama-Pacific meet—that is, not in public,” he told the publication.

I came across Sullivan’s writing and work over the past few years during my research for a forthcoming book on barrier-breaking swimmers who helped launch the modern Olympic age. Titled Three Kings, the book examines the obstacles that class and race played in the 1924 Paris gold medal dreams of the German immigrant Johnny Weissmuller, the Hawaiian Duke Kahanamoku, and Japanese newcomer Katsuo Takaishi. But at least those three had access and opportunity. Women athletes who came before them didn’t, and this was partly due to Sullivan’s handiwork.

In my research I read comments from an American diver named Ida Schnall who was so exasperated with Sullivan that in 1912 she wrote a letter published in the New York Times. “He is always objecting to girls competing,” she lamented. “He has objected to my competing in diving at the Olympic Games in Sweden because I am a girl.” According to Schnall, Sullivan objected to so many elements of female athletes—their comfortable bathing suits, for example—that Schnall said she felt imprisoned in the “last century.”

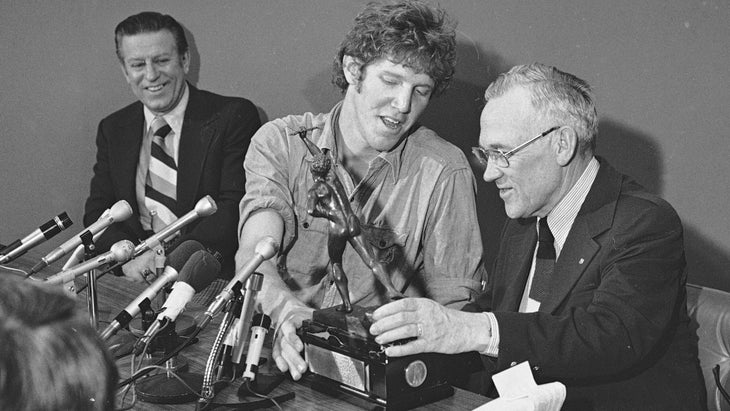

When I recently presented this information to an AAU spokesperson and asked why the organization has not considered changing the name of its most prestigious award, or at the very least begun a public conversation, he vaguely said he would talk to a few people. I didn’t get another call nor an answer to my follow up email. I also reached out to Clark’s professional team, the Indiana Fever, for comment, but did not get a response. She’s hardly the first celebrity athlete to win the prize: the list of Sullivan Award winners includes swimmers Michael Phelps and Janet Evans; NFL players Peyton Manning and Tim Tebow; and Olympic gymnast Simone Biles, among others. NBA legend Bill Walton took home the award in 1974.

Sullivan was a man not to be trifled with. Tall, broad shouldered, and a boxer in his youth, he was easily the most powerful person in amateur athletics in the early twentieth century. He was born in New York City, the son of Irish immigrants, and was a good all-around athlete at the East Side’s Pastime Athletic Club where he wrote about sports even better than he played them. He rose quickly in the amateur sports establishment, editing and publishing the then-bible of the athletic world, Spalding’s Official Athletic Almanac.

By the early 1900s he led the most influential New York club and sporting authority in the country, the Amateur Athletic Union, and was presidentially appointed to organize the American Olympic teams competing in Athens (1896), Paris (1900), London (1908), and Stockholm (1912). He controversially revoked gold medals—most famously that of Jim Thorpe’s in 1913, for taking money in baseball’s minor leagues—and discarded world records—Kahanamoku’s in 1911, for not taking place in the mainland U.S. In overseeing the AAU, Sullivan controlled hundreds of regional sports clubs that made the rules for competition, ratified records, and enforced violations. His contemporaries dubbed him “Big Chief.”

Sullivan’s ugly behavior didn’t stop with sexism. In 1904 he was the director of the Olympics Games in St. Louis, and during the event he helped organize a two-day eugenics experiment called “Anthropology Days.” Sullivan staged parallel games and enlisted indigenous visitors to do western sporting events—the shot put, high jump, long jump, among others—in an effort to prove the superiority of white American athletes to, as he put it, the “average savage.” He had fielded his competition with native men from Japan, Argentina, and elsewhere who had been shipped to St. Louis for a human zoo exhibit at the concurrent World’s Fair. “Barbarians Meet In Athletic Games,” announced a headline in the St. Louis Post Dispatch.

Sullivan tested his subjects in Olympic disciplines they had never seen, never heard of, nor were particularly interested in. His towering presence can be seen in the background of a photo featuring a kneeling Ainu archer from northern Japan. When his Anthropology Days contests were over a satisfied Sullivan declared in his own Spalding’s Official Athletic Almanac for 1905 he had proved “conclusively that the savage has been a very much overrated man from an athletic point of view.” The ethnologist William McGee, who Sullivan recruited to his project, believed the competition established in “quantitative measure the inferiority of primitive peoples, in physical faculty if not in intellectual grasp.”

Sullivan’s deeds and published commentary are , and for years athletes, , and even have called out his opinions as being deeply problematic.

Schnall, the diver, was one of them. She went on to become captain of the New York Female Giants baseball team, but because of Sullivan neither she nor her teammates went to Stockholm in 1912 for the first women’s Olympic swimming and diving competition. While other nations like host-nation Sweden fielded a robust women’s squad, the U.S. prohibited women from “any event in which they would not wear long skirts.”

By contrast Great Britain, Germany, Austria—half of the swimming nations—fielded squads in the inaugural Games. It would take Sullivan’s sudden death in 1914 to clear the way for full women’s participation in the Olympics Games in 1920. And even then Sullivan’s voice still carried. “[The opposition] wasn’t from the general public, it was from the ruling body—they didn’t want women to compete in any sport in the Olympic Games,” recounted Aileen Riggin, a gold medalist in springboard diving, in an oral history she recorded with American Olympic non-profit LA84 Foundation.

Sullivan’s U.S. Olympics teams were successful and his friends adored him, one later eulogizing him as a “great and grand character” whose purpose was “the betterment of the race.” But plenty of others didn’t share those views. Around the same time the Los Angeles Times memorably described him as a “pompous little insect.” Pierre de Coubertin, the founder of the modern Olympics, called his interpretation of the Olympic Games in 1904 “an outrageous charade.”

Some might see Sullivan simply as a product of his times in which race based science and barring women from sport weren’t unusual. He was a NYC Board of Education member and a powerful friend to the city playground movement and the Public School’s Athletic Leagues, which he founded and fostered. At his funeral procession, 50,000 young members were enlisted to line the route. These facts are all part of the established Sullivan resume, some of them listed on the engraved plaque on the permanent AAU/Sullivan trophy on display at the New York Athletic Club.

But Sullivan’s extremist views about gender and race in sports, which were beyond the pale even in the times he lived in, aren’t publicly discussed. The AAU and the New York Athletic Club, the host of the Sullivan Award ceremony, wouldn’t be the first elite institutions to refrain from a deeper look at a founding father.

Todd Balf is the author of the forthcoming Three Kings (Scribd/Blackstone) to be published in July.