On a March morning in 1999, Bertrand Piccard and Brian Jones landed their hot-air balloon in Egypt, completing the . Of the 3.7 tons of propane they’d brought with them, only 90 pounds remained. Piccard, a Swiss aeronaut, stepped out of the gondola and made a resolution: one day he would find a way to ring the globe without using any fuel at all.

The time has come. In March, Piccard, 57, and Borschberg, 62, a Swiss engineer and former fighter pilot, take off from Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, to attempt the first round-the-world flight in a solar-powered plane, the . Over the next five months, the two men will spend a combined 25 days in the air, though only one of them will be in the plane at a time. They’ll trade places at scheduled stops in Oman, India, Myanmar, China, Honolulu, Phoenix, New York City, and either Southern Europe or North Africa, depending on weather conditions over the Atlantic. Piccard hopes the flight will advance clean energy, the way NASA-funded space expeditions led to artificial limbs and better golf clubs. “We need pioneers who show that impossible things can be done,” says Piccard. “Then industry will take over, and one day everyone will think this is normal.”

Piccard and Borschberg spent 12 years and $150 million working with more than 80 engineers to research, design, and test the Solar Impulse 2. The craft resembles a giant glider and has a wider wingspan than a Boeing 747, but its carbon-fiber frame keeps it lighter than a Chevy Suburban. More than 17,000 hair-thin solar cells on the wings charge an array of lithium batteries, which can power the four prop engines for ten hours without sunlight. During the day, the plane will fly at 28,000 feet, where it’s usually clear and the air is thinner. At sunset, the pilot will cut the motors and slowly glide to 5,000 feet to save battery power. The cockpit isn’t pressurized, so an oxygen mask is mandatory.

Life aboard the Solar Impulse 2 will be efficient but a little uncomfortable. Each engine can generate the horsepower of a Vespa, resulting in airspeeds between 22 and 87 miles per hour. Temperatures inside will swing between 104 and minus four, since there’s no heating or cooling system. The plane is susceptible to heavy winds, turbulence, and thunderstorms. Owing to the craft’s minimal undercarriage, ground-crew members will mount e-bikes and ride alongside it to support the wings during liftoff and after touchdown (which will happen only when winds are lowest, often early or late in the day). There’s no backup power in the event that the batteries die. If something goes wrong, the pilot is equipped with a parachute and a life raft.

[quote]“We need pioneers who show that impossible things can be done,” says Piccard.[/quote]

There will also be lengthy ocean crossings to endure—as many as five days and nights of continuous flying. Both men have spent up to 72 hours in a flight simulator and completed three test flights, but neither has flown for such an extended period. Though the plane has autopilot, it’s so sensitive that only a single 20-minute rest every few hours will be allowed during flight. “This is why I like adventure,” Piccard says. “It’s a way to push human performance.”

Part of that involves inhabiting a cockpit that’s barely big enough to lean back, let alone stand up. To help ease cramps, avoid blood clots, and help with digestion, the men will perform exercises designed for tight spaces, like rolling their ankles and flexing their arms. Bathroom breaks won’t be necessary: the seat doubles as a toilet.

“The fact that the cockpit is small is not a problem,” he says. “If you asked astronauts if the capsule was too small when they went to the moon, they probably didn’t even notice. It was too exciting.”

One Adventurous Family Tree

It’s no coincidence that Piccard is one of this generation’s most famous explorers. It’s in his blood.

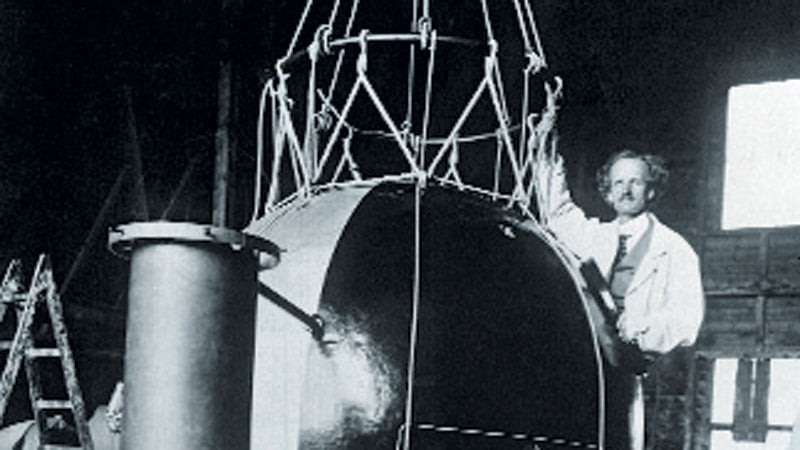

Auguste Piccard, grandfather

Took a balloon to 53,000 feet in 1931 and developed the bathyscaphe to travel to the ocean floor.

Jean Piccard, great-uncle

Invented both the plastic balloon and the cluster balloons used by the U.S. military for atmospheric research. (He and his brother are the namesakes of Star Trek captain Jean-Luc Picard.)

Jacques Picard, father

Jacques and U.S. Navy lieutenant Don Walsh were the first to reach the bottom of the Mariana Trench, in 1960.