In some regards, James Watt was a few decades ahead of his time. He was an unabashedly pro-industry voice and a deeply polarizing leader set on loosening government control over public lands.

But the career of Ronald Reagan’s first secretary of the interior was also swift and controversial. Indian reservations, to this overseer of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, were a “failure of socialism.” Watt’s exit was hastened by a 1983 assessment of his coal advisory board: “We have every kind of mixture you can have. I have a Black, I have a woman, two Jews, and a cripple. And I have talent.” After that statement, Watt was deemed a political liability, and .

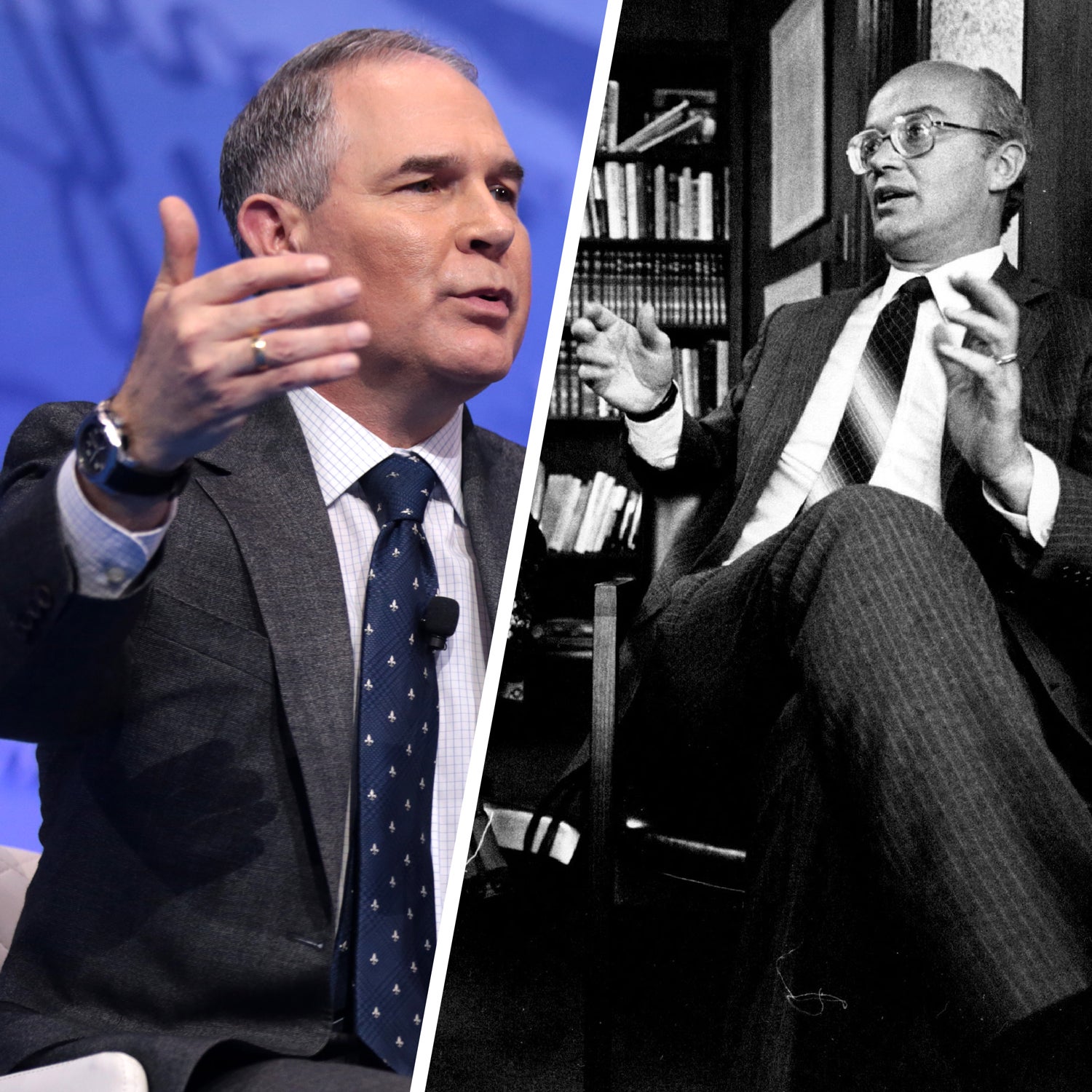

Watt’s brand of politics, as well as those of Anne Gorsuch Burford, Reagan’s Environmental Protection Agency administrator, have reemerged in Washington, D.C. The casual racism and sexism today may come from the president’s own Twitter feed—not a rogue cabinet member—but Watt and Burford’s regulatory actions mirror those of their modern-day counterparts, Ryan Zinke and Scott Pruitt. Stacking government jobs with former extraction industry employees, rushing oil and gas leases, seeming to undermine the very institution they’re appointed to run—it’s the same playbook. Zinke and Pruitt, however, are likely to build a more lasting legacy, historians say, because the behavior that cost their predecessors their jobs has been normalized.

Reagan cruised into the White House on a promise that he would hack at the environmental red tape passed during the decade before. “By the late ’70s, it was becoming clear the [Endangered Species Act] wasn’t just going to save some grizzlies,” says James Skillen, a historian at Calvin College who focuses on public land management. Add to the ESA the National Environmental Policy Act and the Federal Land Policy and Management Act, Skillen says, and “it was having some negative impacts on resource use on public land.” During the campaign, Reagan identified with the return-land-to-the-states Sagebrush Rebellion, and his blunt instruments of choice to enact these policies were Watt and Burford.

At the Interior Department, Watt kicked off his tenure promising that “we will mine more, drill more, and cut more timber.” Similarly, Zinke has said the department’s “goal is an America that is the this world has ever known.” As with their rhetoric, their policies are also coalescing. Watt to oil and gas leases—a practice that rankled Reagan’s California supporters. Zinke, for his part, will offer oil and gas firms a shot at nearly 77 million acres of leases in the Gulf of Mexico come March.

On dry land, Zinke intends to streamline permitting; Watt streamlined it a bit too much. Leases he engineered that offered up more than 1.2 billion tons of Powder River Basin coal were in courts. Investigations by both the General Accounting Office and a House subcommittee found that Watt rushed to hold the sale while demand was low, thus deflating prices. Similar economics define the current oil market.

Déjà vu is even stronger at the EPA. Following interviews with dozens of current and former staffers, the Environmental Data and Governance Initiative (EDGI) familiar to those around during Burford’s time. “The playbook was the same,” says Christopher Sellers, an environmental historian at Stony Brook University and an EDGI interviewer. “The combination of tactics, from trying to shrink the budget to throwing up a wall between political employees and career appointees, the suspicion of career appointees, the hostile work environment…there are so many parallels.”

In two years, Burford (the mother of Supreme Court Justice Neil Gorsuch) cut the EPA budget by 21 percent and staff by 26 percent. “The cuts are so massive that they could mean a basic retreat on all the environmental programs of the past ten years,” the Washington Post . Pruitt, who as Oklahoma’s attorney general made a political career of suing the EPA, wants to cut the agency’s funding by more than 30 percent.

The two administrators with the greatest influence over public land will likely remain for the duration of Trump’s term in office.

Watt and Burford, Skillen says, “had to focus on administrative changes, things within their power.” Trump’s cabinet has followed suit with , shuffling career appointees, and bringing aboard political appointees with ties to industry. According to , 16 Interior Department political appointees and 14 within the EPA were previously affiliated with the oil and gas industry or the Koch brothers’ network—much higher than during the Obama administration. At the EPA, at least since Pruitt took over in March. The offices hardest hit: chemical safety, research and development, and enforcement and compliance. It’s what some would say amounts to .

“At a very basic level, it’s the privileging of economic profit and the viability of industries,” says Lindsey Dillon, an EDGI interviewer and sociologist at the University of California, Santa Cruz, who studies environmental justice. Stacking the EPA with pro-industry employees like this will have a detrimental effect on community health, Dillon warns, especially in already vulnerable communities.

Yet Washington’s tolerance for these actions means Zinke and Pruitt could continue unfettered down the path that doomed Reagan’s appointees. Consider the downfall of Burford. The Superfund toxic waste cleanup program was new at that time, and news emerged that Rita Lavelle, the head of Superfund, may have tipped off her polluting former employer that a federal lawsuit was coming its way. (Lavelle was eventually sentenced to six months in prison for lying to Congress.) Burford, , withheld Superfund documents from Congress. She was held in contempt and later resigned.

Sellers and Skillen both argue that a similar situation is unlikely today. The budget cutting, potential conflicts of interest, and blatant appeals to industry that seemed radical when Watt and Burford brought them to D.C. have since become an accepted norm. Industry-funded think tanks have been churning out policy blueprints for decades. The United States has also become a more polarized place.

Fracking brought oil and gas wealth to states such as Pruitt’s Oklahoma, which then became breeding grounds for an anti-environmentalism GOP movement. “As Watt, in particular, pushed against environmentalists,” Skillen says, “environmental groups’ membership rolls increased. Money increased dramatically, and their alignment with the Democratic Party strengthened.”

The division that Watt and Burford exacerbated—establishing the GOP base as pro-industry and the Democratic base as pro-conservation—may have cultivated a unique element of Zinke and Pruitt’s leadership: the discrediting and politicization of science. As the right fell in line behind the extraction industry and the left behind environmental measures, climate science served as the ultimate wedge. “Some of the things you see today are, in the context of climate change, a rejection of state science and an attempt to muddle science,” Dillon says. Interior planning documents rarely, if ever, mention climate change. Pruitt has routinely dismissed norms about climate change held by the scientific community. Scientists in both agencies are being shuffled to new offices or relieved of their duties.

Because Zinke and Pruitt align so closely with the goals of today’s GOP, and because Washington’s tolerance for scandal is an order of magnitude greater than it was during the 1980s, the two administrators with the greatest influence over public land will likely remain for the duration of Trump’s term in office.

Their fate, then, rests with public sentiment. Watt’s departure was hastened by vulgarity, but crudeness wasn’t the cause. Reagan grabbed some 60 percent of the vote in his “solid West” in 1980, but polls taken in 1981 showed westerners precisely because of Watt’s policies; two years later, Watt’s disapproval rating was higher in the West than nationwide. It’s a reminder that one thing hasn’t changed in Washington since the 1980s: popularity matters.