The Year of Giving Adventurously

Citizen philanthropy is on the rise—and so are the nonprofits. Here are the 30 organizations and innovators truly making a difference, delivering health care in rural Asia, distributing bikes in Africa, and championing preservation in your backyard. Plus: Carbon-eating superplants, why the solar-powered car is MIA, and more.

THE ORGANIZATIONS

Shelterbox

American Himalayan Foundation

Oceana

Kiva

1% for the Planet

Big City Mountaineers

African Wildlife Foundation

American Forests

World Bicycle Relief

Water For People

Climate Counts

Ioby

American Trails

The Marine Mammal Center

Afghan Child Education and Care Organization

Foundation Rwanda

Environmental Defense Fund

Trekking for Kids

American Rivers

Health in Harmony

Pathfinder International

Rainforest Alliance

Technoserve

Vital Voices Global Partnership

World Wildlife Fund

THE INNOVATORS

David Belt

Amy Purdy

Jon Rose

Dan Morrison

HOW TO GIVE RESPONSIBLY

How We Picked Them

Do Diligence

��

Shelterbox

Cornwall, England

BY THE NUMBERS: More than one million natural-disaster victims supplied since 2001

WHO'S IN CHARGE: Tom Henderson, 61, a former Royal Navy search-and-rescue diver and offshore-drilling consultant

WHAT IT DOES: Henderson established in 2000 to offer practical tools to disaster victims so they can help themselves, an approach designed to foster self-reliance and self-esteem. Each $1,000 kit, which comes in a durable box that doubles as a storage container or crib, contains a family tent (torture-tested to withstand high winds, heavy rain, and extreme temperatures), blankets, a multifuel stove, a cookset, a water filtration system, tools, and an activity pack for kids. Teams of volunteers deploy to disaster sites—often within 24 hours—hand-deliver boxes, and teach families how to use them. ShelterBox spent more than $19 million on programs last year; since 2001, it has distributed 110,000 boxes in 150 disaster zones, including the Indian Ocean tsunami of 2004, Hurricane Katrina, and the Haiti earthquake.

EXTRA CREDIT: Individual donations—which go straight to paying for box contents—can be followed with tracking numbers.

LOOKING AHEAD: ShelterBox recently revamped its ShelterBox Academy, which trains hundreds of volunteers every year to operate in harsh, remote locales. It’s now offering more courses for the public, including university classes, corporate team training, and first-aid programs, which raise funds for volunteer education.

American Himalayan Foundation

San Francisco

BY THE NUMBERS: 300,000 Nepalis, Tibetans, and Sherpas served by 140 education, health care, and human-welfare programs this year alone

WHO'S IN CHARGE: Erica Stone, 60, a University of California at Berkeley MBA and former documentary-film production manager who has trekked extensively in Nepal

WHAT IT DOES: The (AHF) was established 30 years ago when financier Richard Blum and a group of climbers and trekkers recognized threats to Himalayan culture from unstable governments and a lack of basic services. AHF supports local partners with the funding, technical assistance, and strategy advice they need. In 2010, the organization provided $3.3 million to these partners for projects in education, health care, and cultural preservation in Nepal, Tibet, and Tibetan refugee settlements in India. Projects range from establishing a hospital for disabled children in Kathmandu to training locals in the Nepali region of Mustang to preserve 15th-century Buddhist temples. One notable current issue: an education-based prevention program fighting human traffickers, who lure as many as 20,000 rural Nepali girls into prostitution or oppressive domestic-servant jobs each year. Board member Jon Krakauer has donated 100 percent of the proceeds from his 2011 e-book “Three Cups of Deceit”—an investigation into the practices of Central Asia Institute founder Greg Mortenson—to the foundation’s anti-trafficking program, which sponsors the girls’ schooling and has assisted more than 10,000 girls over the past 15 years.

EXTRA CREDIT: AHF is creative and committed; spending on programs is consistently high at more than 80 percent.

LOOKING AHEAD: One of AHF’s newest projects is the Tibetan Enterprise Fund, which offers grants and small loans to Tibetan refugees who have viable small-business and farming ideas.

��

Oceana

Washington, D.C.

BY THE NUMBERS: Since 2001, ’s research and political outreach have helped persuade governments to increase protections for 1.2 million square miles of ocean

WHO'S IN CHARGE: Andrew Sharpless, 56, a Harvard Law and London School of Economics grad who’s held top jobs at RealNetworks, New York City’s Museum of Television and Radio, and Discovery.com

WHAT IT DOES: In 1999, several foundations—including the Pew Charitable Trusts and the Rockefeller Brothers Fund—commissioned a study on ocean advocacy and realized that only a tiny fraction of money spent by environmental nonprofits was aimed at ocean protection. Two years later, Oceana was born with a practical mandate: to conduct studies and research, inform lawmakers, and protect degraded oceans through concrete policy. The approach has gotten results. Chile banned shark finning, announced the creation of the world’s fourth-largest no-take marine reserve, and reformed salmon-industry practices to protect wild fish populations. The U.S. also banned shark finning in its coastal waters, and Morocco and Turkey outlawed drift nets, already prohibited by the European Union and the United Nations.

EXTRA CREDIT: Oceana can point to dozens of policy victories on four continents in the past ten years. And it’s one of only a few charities to receive a four-star rating from Charity Navigator three years in a row.

LOOKING AHEAD: Oceana has devised a practical road map to wean the U.S. from Gulf of Mexico oil through measures like switching oil-heated homes to electric power and electrifying 10 percent of cars by 2020—a plan that received a grant from the Southern Alliance for Clean Energy last year.

��

Kiva

San Francisco

BY THE NUMBERS: Since 2005, more than 628,000 citizen lenders have provided $248 million in microloans to small entrepreneurs in developing countries

WHO'S IN CHARGE: Matt Flannery, 34, a former software engineer at TiVo

WHAT IT DOES: In 2004, Flannery was working as a programmer when he took a trip to East Africa to make a documentary about entrepreneurs and saw how much difference small investments can make. In 2005, he launched , which connects citizen philanthropists directly to borrowers in developing countries. In a typical transaction, a potential lender peruses Kiva’s online listings of hopeful borrowers, chosen with help from partner organizations in the field. The lender picks one and makes a loan of $25 or more through PayPal. The borrower—a Tajik peddler hoping to buy rice, say, or a Kenyan farmer buying animal feed—makes the purchase and then repays the loan, which is available for the donor’s withdrawal or future loans. Within six months of Kiva’s founding, all seven of the original borrowers, including a goat herder, a fishmonger, and a restaurant owner, had repaid their loans. Now borrowers hail from 60 countries, and their businesses encompass everything from a Bulgarian bicycle-repair shop to an Internet café in Benin.

EXTRA CREDIT: Philanthropy experts say it often takes an individual’s story to move donors to give. Flannery and Kiva harness that impulse, taking affordable, crowdsourced lending to new levels around the world.

LOOKING AHEAD: In June, Kiva, now working with an $11 million budget, announced its first U.S. microfinance programs, in Detroit and New Orleans.

��

1% for the Planet

Waitsfield, Vermont

BY THE NUMBERS: In 2010, 1,450 companies donated $22 million to environmental organizations through 1%.

WHO’S IN CHARGE: Terry Kellogg, 39, a Yale-trained MBA who was the first director of environmental stewardship at Timberland.

WHAT IT DOES: In 2001, Patagonia founder Yvon Chouinard and Craig Matthews, the owner of Blue Ribbon Flies, hatched a simple plan to encourage businesses to give back to the environment. A business pledges to donate 1 percent of sales to vetted environmental groups—including several on this list—and agrees to be audited annually. In exchange, it can display the 1% logo, designed to encourage consumers to support companies that are giving back. Since then, the organization has raised close to $100 million for more than 2,500 groups, from American Forests to the Shawangunk Conservancy. The money has powered high-impact projects like the Seed Alliance, which is using money from Clif Bar to establish a seed bank to conserve genetic crop diversity. Now signs on an average of one new member every day—from small wineries to large manufacturers in 45 countries—and is on track to become the largest network of environmental funders on the planet.

EXTRA CREDIT: For decades, Chouinard has put his money where his good intentions are.

LOOKING AHEAD: 1% recently enlisted 14 people—including musician Jack Johnson and �����ԹϺ���’s own Christopher Keyes—to help spread the word.

��

Big City Mountaineers

Denver

BY THE NUMBERS: More than 15,000 urban teenagers have taken part in sponsored outdoor trips since 1989.

WHO'S IN CHARGE: Executive director Lisa Mattis, 41, former director of individual giving and director of the scholarship program for Outward Bound

WHAT IT DOES: (BCM) gives underprivileged city kids a chance to experience wilderness adventure. Roughly 83 percent of urban teens who participate in BCM’s trips live below the poverty line, 62 percent have never been outside their home counties, and the vast majority have never seen a starry sky. Drawing on an annual budget of $1.5 million, this 22-year-old nonprofit takes young city dwellers from Denver, Chicago, Minneapolis, San Francisco, Seattle, and Portland, Oregon, on seven-day hiking or canoeing trips in settings like the Boundary Waters and Yosemite National Park. Along the way, volunteer leaders guide teens through a series of challenges that culminate in summiting a peak or completing a long river portage. BCM has devised innovative fundraising techniques, including , in which participants challenge themselves in the same way BCM kids might—by tackling a guided climb of a difficult peak and raising funds through sponsorships. This year, North Face–sponsored athlete Cedar Wright signed on, choosing a self-guided climb on a remote Malaysian island. He hopes to raise $10,000.

EXTRA CREDIT: BCM offers diverse ways to get involved and is one of the largest wilderness programs for urban kids.

LOOKING AHEAD: The group has added single-day and overnight programs to augment its seven-day courses. These offer gateway programs for kids intimidated by longer outings.

��

African Wildlife Foundation

Nairobi, Kenya

BY THE NUMBERS: Currently backing 31 conservation-oriented projects that generate more than $2 million annually for African communities; spent $19 million on programs in 2010

WHO'S IN CHARGE: Patrick Bergin, 47, a former Peace Corps volunteer in Tanzania and project officer for the foundation in Tanzania’s national parks

WHAT IT DOES: Launched in 1961, the (AWF) is one of a growing number of NGOs pushing a more inclusive approach to conservation based on a simple philosophy: local people should be factored into the equation. AWF starts by sending field researchers to identify species and landscapes at risk, then employs a host of education, advocacy, and development plans to give local people sound reasons to care for their land and wildlife. One method is what the AWF calls conservation enterprises—sustainable businesses like wildlife tourism and eco-sensitive agriculture. In 2008, AWF partnered with Rwandan communities to build the swanky, locally owned Sabyinyo Silverback Lodge near Volcanoes National Park. It now attracts well-heeled tourists who come to see rare mountain gorillas, generating a flow of dollars that supports locals with infrastructure and development projects. AWF also brokered a deal between Starbucks and small coffee growers in Kenya. In exchange for adhering to strict ethical guidelines for both labor and cultivation, Starbucks offers farmers lucrative contracts.

EXTRA CREDIT: AWF earned a top rating from the American Institute of Philanthropy. Thanks to its success, its people-centered programs have been emulated widely, particularly in the past decade.

LOOKING AHEAD: The group recently launched a website () that catalogs community-owned safari lodges that conscientious travelers can visit.

��

American Forests

Washington, D.C.

BY THE NUMBERS: Nearly 40 million trees planted in the past 21 years

WHO'S IN CHARGE: Scott Steen, 47, former executive director of the American Ceramic Society, an organization for ceramic engineers and scientists

WHAT IT DOES: Forests are the planet’s most effective carbon sinks, so their health has never been more important. Which is why newly appointed CEO Steen is revamping this old-guard conservation organization—founded in 1875 to establish and protect state and national forests—into a force to battle climate change, boost river and habitat quality, and improve recreation areas. With nearly a third of the staff replaced and a new science advisory board installed, the group is now largely focused on reforestation projects in response to urban need and devastation from wildfires, insect infestations, agricultural clearing, and pollution. This year, introduced 54 new projects, ranging from a 27,000-tree planting effort near Oregon’s Klamath River—to prevent erosion into tribal fisheries owned by the Yurok, Karuk, and Hoopa people—to a project in Cameroon that involves planting 50,000 trees.

EXTRA CREDIT: In the face of climate change and clean-water shortages, forest health has never been more important. American Forests has earned a top rating from the American Institute of Philanthropy.

LOOKING AHEAD: Whitebark pines are known as a keystone species with an outsize ability to enhance ecosystem diversity; they’re also nearly extinct in some parts of the Rockies. American Forests is working with the Forest Service and a team of researchers to identify and breed disease-resistant trees.

World Bicycle Relief

Chicago

BY THE NUMBERS: More than 88,000 bikes distributed and sold in developing nations since 2005

WHO'S IN CHARGE: F. K. Day, 51, executive vice president of SRAM Corporation, the largest bicycle-component manufacturer in the U.S.

WHAT IT DOES: Shortly after the 2004 tsunami hit, Day traveled to Sri Lanka, saw the apocalyptic devastation firsthand, and realized there was a simple, brilliant invention that could speed reconstruction and improve lives: bicycles. Bikes are at least four times as fast as walking and can carry up to five times as much cargo as a person. They improve access to health care and education and facilitate commerce. To put more of them in service, Day created a virtually indestructible, easily fixable bike that costs about $134 to produce. By 2006, (WBR) was born and, in partnership with the NGO World Vision, had distributed more than 24,000 free bikes to Sri Lankans. Since then the organization has built assembly plants in Kenya, Zambia, and Zimbabwe, trained locals to construct bikes, and taught some 700 local mechanics how to maintain them. Now it partners with reputable NGOs already in the field to identify populations in need and create contracts with individuals who promote using the free bikes for productive purposes like getting to school. In 2010, they spent $2.5 million on bikes, plants, and programs.

EXTRA CREDIT: WBR tracks the effects of its programs through third-party studies. Day was picked as one of the top 25 philanthropists by Barron’s and the Global Philanthropy Group last year.

LOOKING AHEAD: The bikes are so sturdy that volunteers at organizations like the World Health Organization and Catholic Relief Services in Africa requested to buy them. Two years ago, World Bicycle Relief initiated a program to sell bikes to organizations; proceeds benefit WBR charitable programs. In 2012, WBR will open a fourth assembly plant, in South Africa.

��

Water for People

Denver

BY THE NUMBERS: The group helped more than 188,000 people gain access to clean water in 2010.

WHO'S IN CHARGE: Ned Breslin, 46, formerly a Mozambique country representative for WaterAid, health and hygiene education manager for Mvula Trust, and development director for Operation Hunger

WHAT IT DOES: It’s estimated that 884 million people lack access to a reliable supply of clean drinking water. Each of ’s projects, carried out in countries from India to Peru, is based on the organization’s four guiding principles: everyone in an aided community gets access to water and sanitation; representatives from local government, NGOs, and the local business community all must sign on to the plan; commitments must span at least ten years; and solutions, such as wells, storage tanks, gravity-fed piping systems, and latrines, are designed to last and grow as populations expand. In an ongoing project in Malawi, 48 new water kiosks were constructed. A local entrepreneur returns regularly to purchase the compost. His family earns enough to pay off the loan and save money, and the businessman sells the compost to farmers for a profit. To support the programs, which cost nearly $10 million per year, the organization has devised innovative fundraising initiatives. The latest: mountaineer Jake Norton is climbing each continent’s three highest summits to raise $2.1 million in donations.

EXTRA CREDIT: For seven years in a row, the project has earned a four-star rating from Charity Navigator.

LOOKING AHEAD: Water for People just released a beta version of FLOW (field-level operations watch), a new monitoring system in which field workers use a cell-phone app to update the WFP website with the status of clean-water access in remote areas. Donors and staffers can chart progress on an online map updated in real time, sending money and volunteers to places that need it most.

��

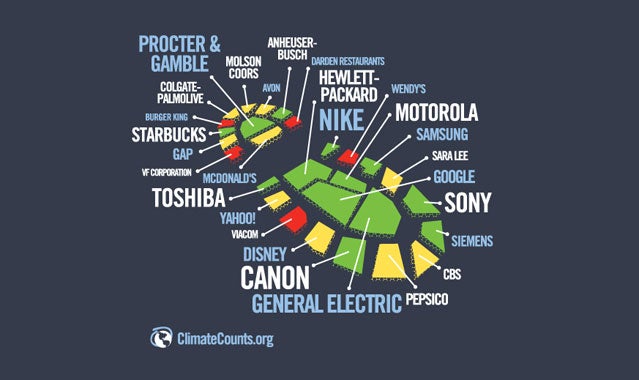

Climate Counts

Manchester, New Hampshire

BY THE NUMBERS: 150 major companies, from Disney to General Electric, are rated annually on their climate practices

WHO'S IN CHARGE: Mike Bellamente, 35, who led a team from the U.S. Economic Development Administration to study how communities were affected by the Deepwater Horizon oil spill

WHAT IT DOES: Launched in 2007 and operated by a small team of sustainability experts and more than a dozen independent researchers, uses a scorecard for corporations, rating them on 22 criteria in four areas: carbon footprint, efforts to reduce impact, support for climate-friendly legislation, and public transparency. With a $350,000 annual budget, the group now looks at companies in 16 high-visibility industries, including airlines, hotels, electronics, food products, and toys. The goal is to encourage consumers to vote with their dollars—ratings are available through the website, a pocket guide, and a mobile app—and to spur executives to reduce their companies’ carbon output. Many firms have embraced the ratings concept; some have even hired corporate sustainability directors as a result.

EXTRA CREDIT: The group leverages a tiny staff’s efforts into positive changes on a large scale. Renowned sustainability journalist and consultant Joel Makower as well as Gary Hirshberg, founder of Stonyfield Farm, a corporate sustainability leader, sit on the board.

LOOKING AHEAD: In 2010, Climate Counts began offering audits, verification ratings, and workshops for smaller, unrated companies that elect to be scrutinized. The group is expanding its ratings with a new scorecard on water use.

��

IOBY

New York City

BY THE NUMBERS: (In Our Back Yards) has raised more than $130,000 for 100 neighborhood environmental projects in New York since 2009.

WHO'S IN CHARGE: Erin Barnes, 31, a former community organizer for the Save Our Wild Salmon Coalition

WHAT IT DOES: In 2007, Barnes, Cassie Flynn, and Brandon Whitney—all recent grads of the Yale School of Forestry and Environmental Studies master’s program—moved to New York City and noticed a curious trend in the environmental movement. Movies like An Inconvenient Truth had galvanized people to take action, but the problems seemed so large and distant that the energy was channeled mainly into green consumerism. Using a digital platform from , the three launched a pilot website that posts environmental projects in the city that could use money and volunteers. Soon, locals in all five boroughs were posting projects like urban farm startups in empty lots, beach cleanups, and beautification days for city parks. With help from IOBY, a group called Velo City raised some $3,000 to support an urban-education program called Bikesploration.

EXTRA CREDIT: IOBY is a young startup but readily supplies financial reports. It’s backed by more than a dozen foundations, including the Kresge Foundation and the Jack Johnson Ohana Foundation.

LOOKING AHEAD: After the successful NYC pilot—this year IOBY expects to raise another $100,000 for neighborhood environmental projects there—plans are afoot to expand to up to three more U.S. cities in the next two years, using $250,000 in seed money from foundations.

American Trails

Redding, California

BY THE NUMBERS: The world’s largest advocacy group for planning, building, and managing trails and greenways

WHO'S IN CHARGE: Pam Gluck, 54, former state trails coordinator for Arizona, recreation director for Pinetop-Lakeside, Arizona, and cross-country ski guide

WHAT IT DOES: Chances are, if you walked any new trails in the U.S. in the past 20 years, (AT) played a part in establishing them. The 20,000-member outfit is the only national organization dedicated to building, expanding, and safeguarding trail systems for all users, from hikers, bikers, runners, and equestrians to dirt-bike and ATV riders. Operating on an annual budget of $295,000, AT provides hundreds of member organizations with guidelines on how to plan trail systems, write grant proposals, negotiate rights of way, and manage urban and backcountry trails. (For example, the Sacramento River National Recreation Trail in California and the Arkansas River Trail in Little Rock were recently built with help from AT.) It secures funding for trail building and maintenance by knocking on doors on Capitol Hill and at numerous federal agencies, including the Forest Service, the National Park Service, the Fish and Wildlife Service, and the Bureau of Land Management. AT contracts with these agencies to run training sessions for trail crews and sponsors an annual national symposium for trail builders and advocates.

EXTRA CREDIT: A host of government agencies, including the Forest Service and the National Park Service, endorse AT, which supports some 22,000 members and 500 grassroots trails organizations.

LOOKING AHEAD: Two years ago, manufacturer GameTime, research firm PlayCore, the Natural Learning Initiative, and American Trails launched Pathways for Play, a program designed to keep kids outside and to help fight childhood obesity. The pilot project, PlayTrails, debuted in an urban park in Chattanooga, Tennessee, in 2010 with six play areas on a half-mile trail. PlayTrails have since debuted in Missouri and North Carolina, and more than a dozen communities nationwide plan to build them.

The Marine Mammal Center

Sausalito, California

BY THE NUMBERS: 30,000 people schooled in marine-science programs each year; approximately 17,000 marine mammals rescued since its inception

WHO'S IN CHARGE: Executive director Jeffrey R. Boehm, 50, formerly the senior vice president of animal health and conservation science for the Great Lakes Conservation Awareness initiative at the John G. Shedd Aquarium in Chicago and a onetime veterinarian at the Los Angeles Zoo

WHAT IT DOES: In 1975, when the (MMC) was founded, this seaside rescue-and-rehab outfit was little more than a first-aid clinic housed in a collection of kiddie pools. Now it’s the largest operation of its kind in the United States, rescuing hundreds of sea mammals each year (from dolphins to newborn seal pups) that are malnourished or have been stranded, beached, shot, struck by boats, bitten by sharks, or tangled in fishing nets. After receiving veterinary care, the creatures are returned to the wild or—if they’re unlikely to survive release—transferred to aquariums or zoos. During the mammals’ captivity, kids from preschool to college age are allowed to come in for a look, and MMC offers educational programs that inspire many of them to consider careers in marine biology. Meanwhile, the group’s 16-person veterinary-science unit has collaborated with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and numerous universities on research topics like the effects of toxic-algae poisoning, a natural occurrence exacerbated by agricultural runoff and warming seas.

EXTRA CREDIT: MMC transforms a simple mission into a force for conservation through education and science. It earned top marks from the American Institute of Philanthropy.

LOOKING AHEAD: Marine mammals are bellwethers of environmental changes, not least because they’re at the top of the food chain. MMC’s ongoing research—for example, on the potential link between PCBs and startlingly high rates of reproductive cancer among seals and sea lions—could help shed light on how those changes affect our health.

��

Afghan Child Education and Care Organization

Kabul, Afghanistan

BY THE NUMBERS: More than 11 orphanages established in Afghanistan and Pakistan since 2003

WHO'S IN CHARGE: Andeisha Farid, 28, a former war refugee from Afghanistan. Before launching AFCECO, Farid worked as a program manager for CharityHelp International’s child-sponsorship program.

WHAT IT DOES: estimates that Afghanistan is home to roughly one million war orphans, many of whom are forced into child labor or a life of begging. Farid, who was educated by Afghan women in a Pakistan refugee camp during the Soviet war in Afghanistan, envisioned a new kind of orphanage, one that would operate with the blessing of home villages by keeping the kids connected to their heritage. After she started her first safe house for 20 kids in Islamabad in 2003, she teamed with CharityHelp International’s child-sponsorship program, which allowed her to expand. Now AFCECO’s three-story orphanages—built in places like Kabul and Islamabad—are oases of learning, where children take classes and participate in soccer, photography, drama, and martial arts. The orphanages harbor more than 600 children, some of whom get a chance to study abroad.

EXTRA CREDIT: Farid’s locally effective approach is also globally inspiring—as an example of the dividends that can accrue from a single salvaged life.

LOOKING AHEAD: AFCECO is raising money for a medical clinic in Kabul that would offer care to both orphans and orphanage employees, many of whom are war widows.

��

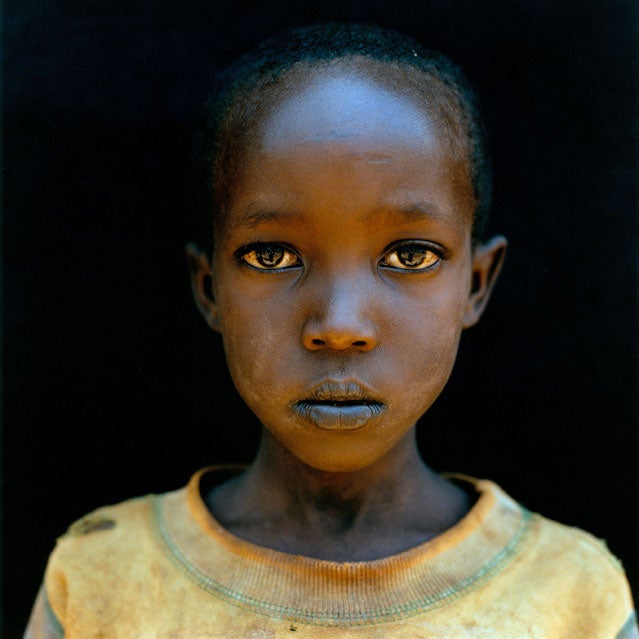

Foundation Rwanda

New York City

Jean-Paul

Jean-Paul assembling a Kona Africa bike

Jean-Paul assembling a Kona Africa bikeAssembling bikes

Foundation Rwanda mothers assembling Kona Africa bikes to give to other Foundation Rwanda families in need

Foundation Rwanda mothers assembling Kona Africa bikes to give to other Foundation Rwanda families in needBY THE NUMBERS: More than 830 children of rape survivors have been educated through sponsorships since 2008.

WHO'S IN CHARGE: Jules Shell, 34, a documentary filmmaker and former creative director at the Andrea and Charles Bronfman Philanthropies

WHAT IT DOES: In 2006, while on assignment in Rwanda, Newsweek photojournalist Jonathan Torgovnik met Margaret, a woman who had not only survived the 1994 Rwandan genocide and weathered multiple rapes but also contracted HIV, given birth to a child, and been marginalized by her community. Torgovnik later returned to produce a book of photographs and, with Shell, a film about the estimated 20,000 Rwandan children conceived through sexual assaults. They established Foundation Rwanda to pay for the children’s education and provide medical services and job training for their mothers. These days, the foundation spends about $283,000 annually on programs. Other initiatives include an oral-health project that offers checkups and dental products, and the Ladies of Abasangiye, a cooperative that trains women in business, English-language, and craft skills. (Upscale retailer Anthropologie recently began importing its handbags.)

EXTRA CREDIT: A triple play of tactics—smart use of media, solid tools, and sound business practices—boosts a marginalized but extremely deserving class of recipients.

LOOKING AHEAD: Foundation Rwanda has announced plans to launch BirthdayBike.org, a program that raises money to buy a bike and a year’s schooling for Rwandan schoolkids.

��

Environmental Defense Fund

New York City

BY THE NUMBERS: Four million acres of private land are now protected under the group’s Safe Harbor program, which helps landowners preserve endangered-species habitat on their property.

WHO'S IN CHARGE: Fred Krupp, 57, former head of the Connecticut Fund for the Environment

WHAT IT DOES: In the 1960s, widespread use of the pesticide DDT threatened the survival of countless American bird species, and a small group came up with a solution that, back then, was strikingly novel: sue the government. The result was a landmark court case that led to statewide and nationwide bans of DDT and, in 1967, to the establishment of the (EDF). The nonprofit continues to pursue unusual tactics, hiring not only scientists and lawyers but also economists and political strategists to devise market-based solutions to broad environmental issues, including climate, oceans, ecosystems, and human health. In the nineties, EDF pioneered corporate partnerships, and their consulting resulted in major corporate changes, such as reducing McDonald’s waste stream by 30 percent and introducing hybrid trucks to FedEx’s fleet. Last year, EDF spent more than $83.5 million on programs like Climate Corps, a summer fellowship that trains MBA students to consult with large businesses on energy efficiency.

EXTRA CREDIT: EDF’s willingness to work with corporate giants like McDonald’s and Wal-Mart has earned them a reputation for cooperative results.

LOOKING AHEAD: EDF is growing a campaign to pass clean-air legislation at the state and municipal levels, since Congress appears stuck. The organization is also working to quantify the economic benefits afforded by natural systems—for example, runoff filtration by wetlands—so decision makers can consider the positive impact in dollars.

��

Trekking for Kids

Washington, D.C.

BY THE NUMBERS: Nearly $400,000 raised for ten orphanages in developing countries since 2005

WHO'S IN CHARGE: José Montero, 40, president of the Montero Group, a D.C.–based consulting firm

WHAT IT DOES: When siblings José and Ana Maria Montero decided to hike the Inca Trail in 2005, they wanted to give something back to the Peruvian community. Their father, Pepe, who’d lost his parents during the Spanish Civil War, suggested raising money for orphanages, and (TFK) was born. Now the small group—which operates mostly with volunteers and an annual budget of about $32,000—organizes walkathon-style treks, bringing money and volunteer labor to remote areas. Each trekker raises a minimum of $1,000 for the chosen orphanage and pays his or her own travel expenses. For two days before the trek, the group completes a project they’ve raised money for, such as building a new dormitory or renovating kitchens. After as many as eight days on the trail, trekkers return and take the orphans on a field trip, like zip-lining, hiking, or visiting a children’s museum. So far, volunteers have gone to Peru, Nepal, Ecuador, Morocco, Guatemala, Tanzania, and Thailand, raising as much as $60,000 for each orphanage.

EXTRA CREDIT: Combines adventure with purpose-driven travel, and every dollar raised for a project goes to the project

LOOKING AHEAD: Upcoming expeditions include Patagonia and Romania next summer. TFK aims to expand corporate sponsorships to cover administrative expenses and increase the number of trips it offers, with programs geared toward college students, families, and corporate team building.

��

American Rivers

Washington, D.C.

BY THE NUMBERS: 200 dams dismantled since 1998

WHO'S IN CHARGE: CEO and president Bob Irvin, 52, a veteran attorney and environmentalist who most recently served as senior vice president for conservation programs at Defenders of Wildlife

WHAT IT DOES: Rivers are valuable for more than just hydropower: they provide clean drinking water, recreational opportunities, and healthy fisheries. For years, (AR) has pushed these and other arguments in an effort to heal North American waterways, and the group has been at the forefront of two big recent anti-dam victories, both in Washington State. This fall, the 210-foot Glines Canyon Dam became the tallest ever removed, restoring more than 70 miles of salmon and steelhead habitat on the Elwha River. The dismantling of the 125-foot Condit Dam has restored 33 miles of steelhead habitat on the White Salmon River, a renowned whitewater run visited by 25,000 boaters annually. The nonprofit group also lobbies for Wild and Scenic designations—which preserve rivers as free-flowing—releases an annual most-endangered list to spotlight rivers in peril, and works with municipalities to push measures to prevent polluted urban runoff from reaching watersheds.

EXTRA CREDIT: AR has earned honors from multiple watchdog groups for its efforts to improve river health.

LOOKING AHEAD: American Rivers helped orchestrate the removal of two major dams on Maine’s Penobscot River. When completed next summer, the effort will restore 1,000 miles of Atlantic salmon runs and canoeing and fishing access. The organization, which spent $8.5 million in 2010, has also helped plan more than 100 dam removals over the next five years.

��

Health in Harmony

Portland, Oregon

BY THE NUMBERS: 14,000 patients treated in ’s Indonesia clinic since 2007

WHO'S IN CHARGE: Kinari Webb, 39, a graduate of the Yale School of Medicine

WHAT IT DOES: Gunung Palung National Park, a 222,000-acre swath of rainforest in West Kalimantan, Indonesia, harbors one of the last major wild populations of orangutans and other rare species such as gibbons, crested fireback pheasants, and clouded leopards. It’s also the watershed for 60,000 people who live in poverty on its margins, often engaging in illegal logging. When Webb first visited as an undergrad studying orangutans, she realized that the high cost of medical care for subsistence farmers was what drove them to log the forest for cash. She returned in 2005 to start Health in Harmony and its Indonesian counterpart, Alam Sehat Lestari—both of which are driven by the philosophy that better health care for locals could improve the health of the forest. She opened a small medical center in the remote town of Sukadana, a mobile clinic, and an ambulance service, and started several projects to help locals develop sustainable alternative livelihoods as farmers and herders. Though no one is refused care, the clinic offers discounts to communities that agree to stop illegal logging.

EXTRA CREDIT: Health in Harmony is supported by a host of foundations and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Great Apes Conservation Fund; members of the board include professors and doctors from Yale, Dartmouth, and Johns Hopkins.

LOOKING AHEAD: Health in Harmony plans to build a $1.2 million hospital in Sukadana, which will provide surgical care for people who now must travel 12 hours or more to get it.

��

Pathfinder International

Watertown, Massachusetts

BY THE NUMBERS: More than 3.75 million people received HIV and AIDS services through Pathfinder-supported projects in 2010

WHO'S IN CHARGE: In February, Purnima Mane will take over as president, replacing longtime leader Daniel E. Pellegrom. Mane is currently the assistant secretary general of the United Nations.

WHAT IT DOES: Overpopulation can lead to poverty and conflict and can overtax water supplies, arable land, and other resources. was founded in 1957 to expand access to basic health and reproductive services so individuals in developing nations can plan families and build sustainable communities. With $90 million to spend each year, the organization reaches people in more than 25 countries with a range of local programs. In the past two years, these have included establishing a solar-powered blood bank in Nigeria, distributing delivery kits with medication for rural births in Bangladesh, and training Red Cross staffers to prevent postpartum hemorrhages in refugee settings in Tanzania. Through a project in Bihar, India, Pathfinder helped educate more than 650,000 youth in 700 villages about contraceptives. The program resulted in an average 2.6-year increase in the age of marriage and a 1.5-year increase in the age of mothers at first birth.

EXTRA CREDIT: Pathfinder spends 88 percent of its budget on programs.

LOOKING AHEAD: Recently, the group partnered with the Nature Conservancy and the Frankfurt Zoological Society on a plan to establish sustainable fisheries, healthy forests, and health care in a remote, wildlife-rich area of western Tanzania, where populations are outpacing natural resources.

��

Rainforest Alliance

New York City

BY THE NUMBERS: More than 167 million acres of forests worldwide are now rated as sustainable under Rainforest Alliance’s certification system

WHO'S IN CHARGE: Tensie Whelan, 51, a former journalist and consultant who has worked with the National Audubon Society and the League of Conservation Voters

WHAT IT DOES: Established during the rainforest crisis of the 1980s, 25-year-old aims to preserve the biodiversity of forests worldwide by creating conservation-friendly livelihoods for locals. Its programs center on sustainability-certification labels for forestry, tourism, and agricultural businesses, which can just as easily be forces for conservation as for devastation. Certification guidelines and training programs help farmers, foresters, lodges, and tour guides build sustainable businesses. The labels are also designed to encourage consumers to purchase conscientiously. (Companies like Newman’s Own Organics, Naked Juice, and Whole Foods buy Rainforest Alliance–certified coffee, cocoa, bananas, and tea.) The organization offers a free grade-school curriculum—downloaded and viewed online eight million times since 2003—to teach kids about the animals and people living in the rainforest.

EXTRA CREDIT: The demand for sustainable goods has never been higher, and Rainforest Alliance–certified products sell to companies with major impact, like Dole and Wal-Mart.

LOOKING AHEAD: In 2007, Rainforest Alliance launched a climate-change program, which helps farmers reforest unused lands, and recently raised its standards for sustainable beef production.

��

Technoserve

Washington, D.C.

BY THE NUMBERS: Since 2010, an estimated 40,300 people employed in 30 countries with the help of ’s programs

WHO'S IN CHARGE: Bruce McNamer, a 49-year-old Stanford MBA, formerly an investment banker at Morgan Stanley, a management consultant at McKinsey, and a Peace Corps volunteer in Paraguay

WHAT IT DOES: While working in a hospital in Ghana in the 1960s, Technoserve founder Ed Bullard realized that local farms and businesses languished not because of a shortage of motivation or ability, but because of a lack of resources, both educational and financial. He started Technoserve in 1968 to connect entrepreneurs in developing countries with capital and educational resources. The organization started primarily with small farmers, but now, with a $58.3 million annual budget, it works to strengthen entire industries, such as coffee and cocoa. Some 1,000 staffers, mostly natives with successful business experience, train entrepreneurs in skills from writing business plans to applying fertilizer; connect them to finance organizations and corporations that can purchase their goods; hold business-plan competitions; and lobby to improve regulations. The results can be tangible for beneficiaries like Nicaragua’s Jorge Salazar Cooperative of farmers, which, with Technoserve’s help, started planting high-value crops like rare criollo cocoa and built a plant for processing malanga, a local tuber. The co-op then reinvested its profits to build a pharmacy and support local schools and police.

EXTRA CREDIT: Technoserve enlists volunteer consultants from companies like McKinsey and L’Oréal. It’s top-rated by the American Institute of Philanthropy.

LOOKING AHEAD: Technoserve recently received a grant from the Clinton Bush Haiti Fund to help develop Haiti’s business sector along with initiatives like the Haiti Hope Project, a partnership with Coca-Cola to help mango farmers find new markets and financial backing.

��

Vital Voices Global Partnership

Washington, D.C.

BY THE NUMBERS: 10,000 emerging women leaders trained in 127 countries since 1997

WHO'S IN CHARGE: Alyse Nelson, 37, former deputy director of the Vital Voices Global Democracy Initiative at the U.S. Department of State

WHAT IT DOES: This NGO sprang from an acclaimed U.S. State Department program, Vital Voices Democracy Initiative, established in 1997 by Hillary Clinton and Secretary of State Madeleine Albright. Working with the UN, EU, World Bank, and international governments, the program organized conferences for hundreds of emerging women leaders. In 2000, (VVGP) was established to continue the mission by combating human trafficking, supporting women entrepreneurs, and advancing women in politics and public leadership. The goal is for each woman touched by VVGP’s programs to pay it forward. In 2008, Ghanaian Brigitte Dzogbenuku, general manager of a fitness center in Accra, spent five weeks in the U.S. taking skills seminars and shadowing Donna Orender, president of the WNBA. After returning to Ghana, she founded Hoop Sistas, a girls’ basketball program that offers career development and women’s health workshops.

EXTRA CREDIT: Big reach with steady results; consistently receives four-star ratings from Charity Navigator

LOOKING AHEAD: In 2012, VVGP will expand programs in North Africa and the Middle East.

��

World Wildlife Fund

Washington, D.C.

BY THE NUMBERS: More than $1 billion invested in roughly 12,000 projects in 100 countries since 1985

WHO'S IN CHARGE: Carter Roberts, 51, a Harvard MBA who spent 15 years leading domestic, international, and science programs at the Nature Conservancy

WHAT IT DOES: The (WWF) was founded in 1961 with a deceptively simple mission: to conserve species. It soon realized that in order to do that, it needed to preserve the land and oceans those species live in—and that triage was in order. Over the years, the organization has homed in on 19 hot spots of biodiversity experiencing grave threats, such as the Amazon, the eastern Himalayas, and the Arctic. Now operating out of 100 offices worldwide, WWF employs a strategy heavy on fieldwork and scientific studies, which staffers use both to develop solutions at the village level and to affect policies and consumer behavior. One solution WWF pioneered: sustainable-business certifications that encourage better business practices and informed purchasing among consumers.

EXTRA CREDIT: WWF’s name recognition and budget allow it to implement projects and initiatives that cross political borders and incorporate dozens of complicated partnerships, a difficult feat for smaller groups.

LOOKING AHEAD: Through its Market Transformation Initiative, WWF is working with about 100 multinational corporations—50 partnerships are already established—that provide staples like soy, beef, and sugar. The idea is to help companies institute sustainable practices on all levels, from harvesting to packaging. Critics decry WWF for sleeping with the enemy—the organization takes consulting fees—but its success is undeniable. In the past four years, with WWF’s help, Coca-Cola has improved water efficiency by 13 percent and reduced carbon emissions by 6 percent.

David Belt

Bright idea: New-school urban playgrounds

In July 2009, in a blighted junkyard along the borough’s Gowanus Canal, a tree grew in Brooklyn—actually, a tree, a bocce court, lounge chairs, and three swimming pools made from converted dumpsters. For the next two months, this lo-fi country club hosted barbecues, birthdays, and mixers, offering locals a taste of leisure life inside the hardscrabble city.

The project, called Dumpster Pools, was the work of David Belt, a 44-year-old real estate developer who grew restless a few years ago and decided to chart a new course. To that end, he began turning what he calls “junk spaces”—abandoned big-box stores, run-down urban lots—into inspired community rec centers and art projects. In May 2010, Belt and his colleagues at —a rotating crew of like-minded friends and designers—took on the “boring act of recycling,” as Belt puts it, by building a 20-by-30-foot clear box, with high walls made of steel and bulletproof glass, on a private Brooklyn lot. Locals were invited to smash bottles against the glass, which was wired to trigger nightclub-style flashing lights. The shards were all recycled.

Both projects were funded entirely by donations and built mostly by volunteers. In 2012, Belt is expanding, with new projects in Philadelphia (where he refurbished 27,000 square feet of an old warehouse and church as a rec-and-learning center) and Detroit (an industrial-wasteland skate park). The coolest of Macro Sea’s future visions: a series of five-story artificial ice cliffs for urban mountaineering, which Belt hopes to bring to Manhattan high-rises someday. The challenge is finding ice coils large enough to keep the walls solid for weeks at a time, but Belt doesn’t seem worried. “We’re not afraid of scale,” he laughs.

Amy Purdy

Bright idea: Disabled adventurers go big

Purdy is one of the country’s most effective advocates for disabled outdoor athletes, and she came to her work the hard way: by losing both legs below the knees when she was 19. In the summer of 1999, bacterial meningitis sent her body into septic shock and set off a cascading series of organ failures that nearly killed her. A week before, she’d been a rising young snowboard competitor; suddenly, it looked like her career was over.

“I was lying in my hospital bed, watching the X Games on TV,” Purdy says, “and I remember thinking that if I could see just one person competing with a prosthetic leg, everything would be OK.” There weren’t any, but working with a prosthetics expert, Purdy created a leg with an articulated ankle joint that allowed her to bend her knees on a board. Within a year and a half, she was competing again. Since then she’s won three gold medals in adaptive events, most recently at the New Zealand Para-Snowboard World Cup.

In 2005, Purdy and her boyfriend, Daniel Gale, founded (AAS) to give other disabled athletes a path into extreme activities—from motocross to snowboarding to skateboarding. In addition to taking wounded veterans onto the slopes and halfpipe, AAS has created a competitive circuit for disabled riders and hopes to bring boardercross to the Paralympics by 2018. “When I lost my legs, there were no opportunities to move forward in snowboarding,” she says. Now, thanks in part to Purdy, there are 81 adaptive snowboarders competing around the world.

Jon Rose

Bright idea: DIY disaster relief

In September 2009, California surfer Jon Rose was sailing toward the island of Sumatra, carrying ten water filters that he planned to deliver to a rural community while enjoying a surf trip in Indonesia. Rose was looking to move on from his career as a Quiksilver-sponsored surfing pro. Inspired by his father’s nonprofit, RainCatcher, which teaches African villagers how to filter rainwater, he hit upon the idea of recruiting surfers to deliver water filters in their travels through developing countries. He thought it would be a pet project. Then, on his first mission, an earthquake hit nearby, devastating the city of Padang. “It was like divine intervention,” Rose says. “Like, ‘OK, this is your life. This is what you’re doing.’ ”

Rose’s organization, , has since provided some 2.5 million people access to safe water, delivering more than 75,000 simple portable filters, which can be used with local water supplies and whatever buckets are at hand, cutting out the need to dig wells or use purification chemicals. The group is one part viral campaign—looking for volunteers to buy and distribute filters abroad—and one part action squad, running relief and improvement programs in Haiti, Brazil, Pakistan, Indonesia, Kenya, Uganda, India, and Liberia. It’s a style that Rose refers to as “black ops” or “guerrilla humanitarianism,” which he defines as working “under the radar and around the red tape.” That means a lean budget and a skeleton staff that coordinates with locals on the ground and moves into and out of target areas quickly.

Those years he spent far off the beaten path prepared him for his new job, Rose says. “It’s sort of the same way I felt about surfing as a kid,” he says. “But it’s greater.”

David Milarch

Organization: Archangel Ancient Tree Archive

Bright idea: New old growth

David Milarch discovered his calling as a tree evangelist during a near-death experience from renal failure 19 years ago. “When I came to, there was a ten-page outline that I don’t remember writing,” says the cofounder of this Michigan-based environmental group. His mission, dictated (he sincerely believes) by the Archangel Michael: to clean up the planet’s air and water and reverse the effects of climate change by cloning the world’s biggest, oldest trees.

Once a hard-living biker, Milarch developed a passionate spiritual connection to old-growth trees—especially redwoods and giant sequoias. Both species can live for millennia, pumping out oxygen and sequestering tons of atmospheric carbon. Milarch, along with his son Jared and project coordinator Meryl Marsh, started taking cuttings from the tops of the most titanic redwoods and sequoias they could find, as well as sprouts from huge stumps. Working in a Monterey, California, greenhouse and using various propagation techniques, project consultant Bill Werner has coaxed bits of the plant tissue to root and grow into field-ready transplants. also maintains living libraries of more than 40 cloned species, from an ancient Monterey cypress to thousand-year-old Irish oaks.

Some scientists have questioned whether genetic material alone is responsible for the trees’ size and longevity, arguing that favorable growing conditions could just as likely explain it, but Milarch sides with his science adviser, the eminent redwood geneticist William J. Libby. Next year, Milarch hopes to start planting redwood saplings in San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park, and he’s looking for investors to underwrite other planting projects in the U.S. and abroad. “We want to rebuild the world’s first old-growth redwood forest,” he says. “They’re the most iconic trees on earth.”

Dan Morrison

Organization: Citizen Effect

Bright idea: Donations with destinations

Dan Morrison understands the power of face time. While traveling through India in 2006, he met a woman who said her earthquake-ravaged community needed a well but didn’t have the $5,000 required to build it. Back home in Washington, D.C., he sent out a card pledging $2,500 and asking acquaintances to join him. Within days, $500 checks started arriving—from a friend, a former roommate, and Morrison’s high school English teacher, among others. A lightbulb went off. “I realized that with fundraising, it’s critical to have a specific project people can wrap their minds around,” says Morrison. “That the request was coming from someone they knew made it that much more effective.”

In December 2008, Morrison created 1Well, a nonprofit that helped people make investments in high-need areas around the world. Soon after, he quit his job as a consultant on Middle East policy to focus on 1Well full-time. In 2009, spurred by a $300,000 grant from Google’s executive chairman, Eric Schmidt, and his wife, Wendy, the group morphed into , an online fundraising platform that connects citizen philanthropists with vetted, small-scale projects around the world. Budding do-gooders visit the website and choose a country, a fundraising goal, and a focus area (food security, education). In 2011, the group raised close to $500,000, funding 339 projects to date.

The twist comes in picking a fundraising approach—like the cross-country bike ride that Boulder, Colorado’s Glenn Olsen did to raise money to build indoor toilets in Bandwhad, India. “When you do what you love in the name of a good cause, it’s more fun for everyone,” says Morrison, who believes that many people who might skip a specific objective (eliminating dysentery in South Asia?) will be lured in by an individual putting forth so much effort to help.

How We Picked Them

To compile our list of top philanthropies, we polled everyone from fellow journalists to independent experts who keep track of nonprofits all over the world, and we used Facebook and Twitter to broadcast our interest. We also brought in Kate Siber, a tireless Colorado-based writer who spent weeks beating the bushes for capable nonprofits that are doing work that is both worthwhile and innovative. Siber relied on ratings from organizations like Charity Navigator and Charitywatch, but she also looked to other credibility factors, including partnerships with government agencies and NGOs, transparency (does the organization clearly spell out its mission and the results it’s achieved?), efficiency (how much is spent on programs instead of overhead?), and scope. Your favorites aren’t on the list? Tell us all about them at fixtheworld@outsidemag.com. It’s a big planet out there. No doubt we’ll be doing this again.

Do Diligence

How to size up charities on your own

There are 1.6 million nonprofits in the U.S., but only a small number are rated by groups like Charity Navigator () and the National Center for Charitable Statistics (). Interested in one that hasn’t been vetted by either? Do your homework using their methods.

Check financial health. Efficient charities spend at least 75 percent of their annual budget directly on programs, according to Charity Navigator. An organization should be able to provide recent 990 forms—an annual report to the IRS, required of most nonprofits, describing their mission and finances—online or upon request.

Assess executive compensation. You don’t want to spend too much on somebody else’s salary. Be aware that average executive pay for the largest 5,500 organizations is $150,000, but highly effective organizations may spend more for a seasoned CEO.

Consider reputation. Grants from well-known groups, such as the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, or contracts with government agencies lend organizations credibility, since they require detailed vetting. Do a search of the organization on Google News for any red flags.

Request the organization’s policy on donor relationships. Most will agree not to sell your contact information to other groups or will offer you the opportunity to opt out.

Investigate results. Established charities should be able to demonstrate the need for their services, report their activities, measure their results, and communicate all of it clearly. If the group is small and local, observe projects in your area.