I heard the rumbling before I saw anything. My first thought was that it might be a military jet dipping low through the alpine valley, as sometimes happened. But that didn’t make sense; it had been snowing all day, and clouds still hung over the Elk Mountains of Colorado, just outside the ski-resort town of Crested Butte.

Late in the afternoon, after alpine skiing all day, I’d decided to go for a quick cross-country jaunt on one of my favorite trails, a forest road leading to an old ghost town now used as a biological-research station in summer. In winter the road is closed to vehicles, and it’s a fun four-mile out-and-back ski. I was pushing it, but figured I’d make it back by dark.

At the time, I lived in the East and had little notion of what can happen when new snow falls on top of old snow in big, steep mountains. I clicked in and followed the tracks, gliding through stands of aspens and, without realizing, crossing two active avalanche paths along the way.

Eventually, the trail emerged into a big meadow, right at the base of Gothic Mountain, so named because its rocky flanks resemble cathedral buttresses and drop steeply down into the valley. It’s only 12,000-some feet high, not much by Colorado standards, but it’s one of my favorite peaks, nature’s answer to Chartres. I started across the meadow, planning to tag the edge of the ghost town and then head back.

I’ve loved cross-country skiing since I was in third grade. Even as a little kid, I preferred the quiet of the woods to launching off jumps at Greek Peak, our local alpine hill in upstate New York. At the time, in our comfortable university town, it wasn’t great socially to have parents who were getting divorced. I got sent to the principal’s office a lot. The snowy woods held more appeal than the playground.

What’s that sound?

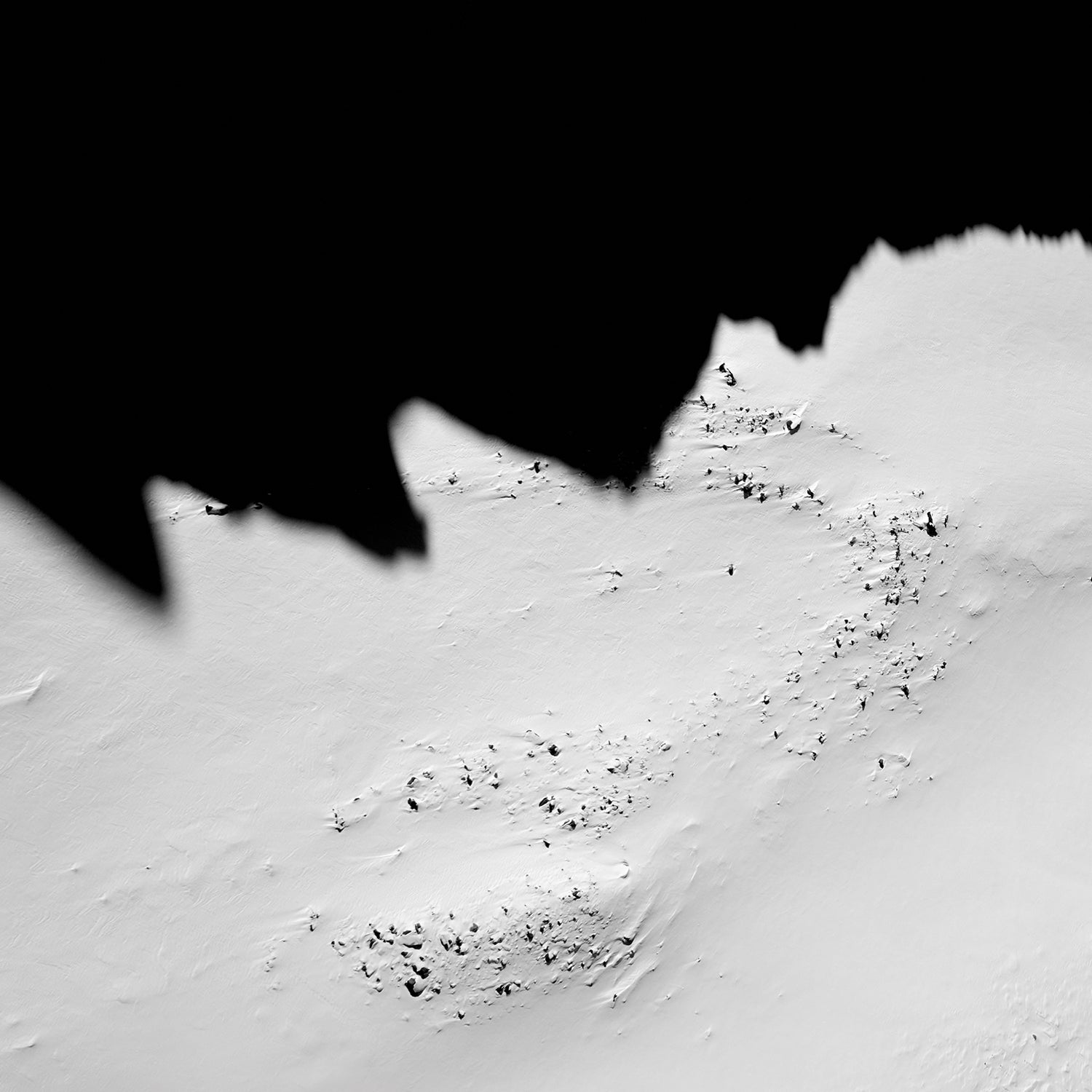

My eyes moved up the flanks of Gothic. The entire side of the mountain, a vast snowy bowl, seemed to be moving, as if all the snow had decided to flow downhill at once, from top to bottom. A cloud formed at the leading edge of the slide, billowing up like the foam of a breaking wave. Oh right, I thought: This is an avalanche. I’m actually seeing one. Shit.

The cloud billowed higher and the roaring got louder as the snow funneled down to a narrow choke point right above a cliff face. For some reason I expected it to stop there, but of course it didn’t. The funnel concentrated the slide’s energy, and the river of snow poured over the cliff wall with unbelievable force, like water blasting out of a dam. It kept going, plowing through the trees now, heading in my general direction. I took five frantic strides back up the trail, but it was clear the avalanche was too big to outrun if it had the momentum to reach me. I stopped and watched it come.

This was not your ordinary release; it was a massive deluge. A person caught in it would have no chance. I felt ordinary and small, like a wild animal that knows, deep inside, that Nature doesn’t care whether it lives or dies.

I was experiencing what the University of California at Berkeley psychologist Dacher Keltner defines as awe: “Being in the presence of something vast that transcends our current understanding of the world.” That it did. Keltner says that awe is at the root of religious feeling and creative inspiration; it’s essential, he believes, to maintaining our emotional equilibrium. We need this connection to something larger—to things we can’t understand.

Awe has fallen on hard times lately, in part because we can all witness such wonders—avalanches, giant waves, breaching whales—on our phones. I didn’t have a phone with me that day, or a camera. But I can replay the memory as vividly as if it happened yesterday.

The snow cloud billowed across the valley, pellets of ice stinging my face. I turned away to breathe, bracing myself. Would the river of white reach me? Or would it lose momentum first? It petered out on the flats, but the flying snow took a while to settle. It was getting dark, but I could see the trail well enough to follow the tracks back toward the trailhead, crossing those other avalanche pathways I didn’t know were there. Eventually, I could see the lights coming on in big ski houses, twinkling between the trees. My car was the only one left in the parking lot.