THE TOWNS IN Canadian County, Oklahoma, stand like so many thousands of others out on the prairie—anonymous grids of streets and continuous brick facades stamped into the plains by the same great waffle iron.

Timmer’s armored Dominator 3 chase vehicle.

Timmer’s armored Dominator 3 chase vehicle. ‘Storm Chasers’ costar Tim Samaras, who died during El Reno.

‘Storm Chasers’ costar Tim Samaras, who died during El Reno. ‘Storm Chasers’ costar Reed Timmer.

‘Storm Chasers’ costar Reed Timmer.Not much has happened in this rural area 30 miles west of Oklahoma City since the county was settled in one afternoon during the April 22, 1889, Land Run. And then—as in Greensburg, Kansas, and Joplin, Missouri, two main-street towns you'd never heard of until they were almost blown off the map—something did.

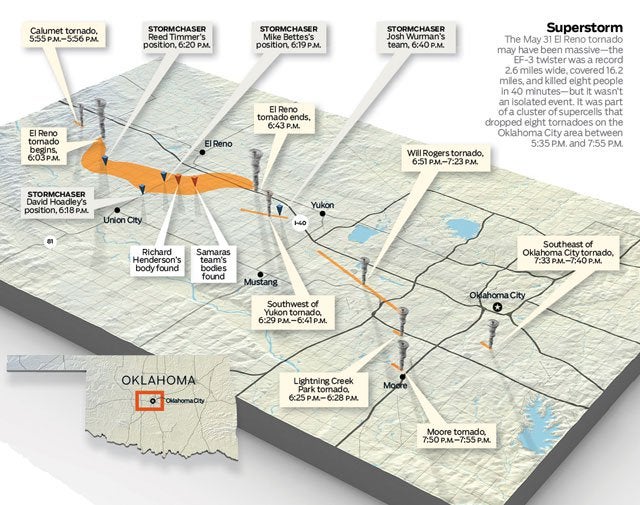

The tornado that touched down in an open field at 6:03 P.M. on Friday, May 31 took the name of the town El Reno, but it was not a single tornado in the traditional sense, nor was it confined to one municipality. Part of a larger system that dropped eight tornadoes across Oklahoma's midsection, it traveled 16.2 miles, enveloping lines of cars caught at a standstill in rush-hour traffic on Interstate 40 before dissipating at 6:43. Panicked motorists began crossing the median and driving up embankments, unsure where to go. Several families took refuge in culverts, only to have them inundated. In all, 22 people died, most in flash floods closer to Oklahoma City. Fresh in everyone's mind was the two-mile-wide, neighborhood-razing tornado that had struck the nearby suburb of Moore on May 20, .

Around 6:30, Canadian County sheriff's deputy Doug Gerten went to check on his 115-acre farm and workshop southeast of El Reno. “When I bought it in 2001, it was a wheat field,” says Gerten in a flat prairie twang. “Everything we did out there we did by hand ourselves. My workshop and everything. We built that as a family.”

In his spare time, Gerten runs a construction business out of the shop, specializing in—”ironically,” he says—tornado shelters. He arrived to find the shop and small house blown apart. The El Reno tornado was still churning up earth to the north, and the wind raced toward it over rippling fields. Up there in that chaos, Oklahoma's highway patrol was hopelessly trying to keep motorists out of its path.

But not everyone was fleeing: some drivers were trying to get closer to the spinning winds. Up to 300 stormchasers, including cell-phone-camera-wielding Okies, local news crews, –funded researchers, hobbyists, enthusiasts, photographers, vanloads of storm tour groups, and field trips from at least four universities, were on the hunt. They were lined up like fans outside a rock concert on the southeast side of the storm, near Union City, but that was nothing compared with the rush-hour traffic streaming out of Oklahoma City.

At 6:30, on Highway 81, meteorologist Mike Bettes and his crew crawled out of their totaled GMC Yukon. Reed Timmer, 33, costar of the Discovery Channel show , stopped with his team in one of their custom armored Dominator vehicles to check on Bettes and company. The Dominator's steel hood had been ripped off by a downed power line.

A few minutes later, Deputy Gerten headed half a mile north and then a mile west from his property, still in open country. Just off 10th Street, 40 yards out in a debris-strewn canola field, something caught his eye. A car? Maybe. “It was kind of wadded up,” he says. “It was hard to tell, the damage was so severe.” Hail marbles began falling. Gerten radioed his dispatcher, waited for the storm's hail core to pass, and waded into the matted stalks.

Three of the car's wheels had been torn away completely, but the fourth bore a Chevy emblem. It was a Cobalt, the sort of midsize sedan you might find on an airport rental lot. Inside, the seats were folded back, “like you'd take a nap,” Gerten says, and a single body was belted, facedown and shirtless, in the passenger seat. The man's shoes and one sock were missing. “I knew it was probably a storm spotter, because there was part of a laptop in the car and a power inverter in what was left of the trunk,” says Gerten. The driver's-side seat belt was still buckled, but the chair was empty. “Once we ran the VIN and it came back to the Samaras family,” says Gerten, “I knew that name rang a bell.”

The man in the passenger seat was Tim Samaras, an engineer, Timmer's Storm Chasers costar, and coauthor of the 2009 memoir . At 55, he had been among the most respected storm-chasers. He'd been bitten by the weather bug early; his brother Jim credits for sparking Tim's tornadophilia. Samaras had been hoping to deploy weather probes into the storm with his 24-year-old son, Paul, a videographer, and meteorologist Carl Young. Samaras's research company, Twistex, based out of Bennett, Colorado, just east of Denver, used a small fleet of Chevy Cobalts and larger trucks to gather data and shoot storm photos and video.

Gerten's radio sounded. “I've got another one down here,” came the call from Lieutenant Jason Glass, a dog handler out on patrol after the storm. It was Young. He'd been sucked from under the driver's-side seat belt and deposited in a rain-swollen right-of-way ditch a half-mile west of the car. The receding floodwater soon revealed Paul Samaras's body another 60 feet west of Young.

AMONG STORMCHASERS, El Reno will be remembered as the tornado that changed everything. That's both because so many of the chase community's notable figures were caught up in the throng and because it was the first time a twister had ever culled their ranks. It was also an uncommon meteorological beast. The tornado was what's called a multiple-vortex mesocyclone—a giant rotating cloud filled with faster-spinning vortices.

“I'm sure this tornado will be the subject of many theses for years to come,” says David Hoadley, the 75-year-old Bismarck, North Dakota, native often credited with being the first modern chaser.

Initially, El Reno was given a moderate EF-3 rating by the of the National Weather Service (NWS), in Norman, Oklahoma, with a damage path 1.4 miles wide and ten miles long. (EF refers to the Enhanced Fujita rating scale, which ballparks tornado damage from 0 to 5, with 0 being a nuisance and 5 being catastrophic; the May 20 Moore tornado was an EF-5.) The rating puzzled many who left messages on the online forum of the chaser publication magazine. Some reported seeing small funnels dancing out of the storm base; others had observed a slowly turning ground scraper. They were all correct. On Tuesday, June 4, the NWS lab upgraded El Reno to EF-5, with 295-mile-per-hour peak winds and an unprecedented 2.6-mile-wide damage path—the largest tornado ever recorded. In September, to confuse things further, they bumped it back down to EF-3, because the largely rural area sustained little actual property damage. Even as an EF-3, though, El Reno was off the charts, confounding the basic funnel taxonomy of stovepipes, elephant trunks, and wedges.

As with word of the storm's true scale, news of the Twistex deaths also took a few days to reach the chaser community. When the tragedy was confirmed that Sunday, a narrative quickly emerged that Samaras was safety conscious and conservative. Timmer, his Storm Chasers costar, praised him as “a pioneer of science and a hero” who died to save others. Like many researchers, Samaras had been attempting to solve the mystery of tornado-genesis—how and why violent tornadoes form—a topic that, after 60 years of study, still isn't well understood.

Samaras, said Timmer, was “doing it for the science.” This is a phrase you'll hear many stormchasers use as a declaration of purpose, one as noteworthy for the knee-jerk defensiveness it reveals as for the elements of truth it contains. That's because storm-chasing has gotten very popular lately, and El Reno exposed some of its growing pains. The clearest picture of the trouble came from a weather geek out of Denver, Eric Carlson, who made an animation of a road map overlaid with the El Reno tornado and roughly 100 chase vehicles broadcasting their locations via the popular Spotter Network service. The video looks like an Atari rendering of Pamplona, with little blue arrows scattering to get out of the way of a stampeding white bull.

While no hard data exists on the number of stormchasers in the U.S., there are some hints. The NWS's SkyWarn program has some 290,000 volunteer spotters who report observations of severe weather. Meanwhile, according to founder Tyler Allison, the nonprofit Spotter Network claims roughly 37,000 “highly engaged spotters” who will deploy when there's a good storm in the neighborhood. Probably only 500 of these are what Allison calls actual chasers, people “willing to drive hundreds if not thousands of miles a year” in search of tornadoes. These diehards begin each spring on the southern plains, where tornado season peaks in May. Then they move north, following the storms as summer progresses.

In the aftermath of El Reno, news outlets broadcast segments asking whether stormchasers were morally challenged tourists who make vacations out of other people's misery. Some called for regulation. The reports ran plenty of thrilling “torn porn” B-roll shot by the very people in their crosshairs. Using Carlson's El Reno animation, one Oklahoma City news anchor made the case that stormchasers pose a public-safety hazard. John Francis, who directs research and exploration at the National Geographic Society, one of Samaras's sponsors, told that the scene, with its traffic jams and explosion of commercial tour operators, “reminds me a little bit of Everest.”

The phenomenon is known as chaser convergence, a reference to the meteorological concept, which describes opposing winds colliding to form storms. “Most of the time a tornado comes down, kicks up a few prairie dogs, and that's it,” says David Hoadley. “You've got a beautiful storm and nobody's the worse for it.” But in a metropolitan area, chasers run the risk of hampering emergency services or even adding to the casualties. In short, you need a reason to be there. Among the justifications that chasers give, science is king. “Ground truthing”—calling in observations to the National Weather Service—is a close second. The trouble is, all these roles are self-defined.

“Believe me,” says Josh Wurman, 53, who runs the private Center for Severe Weather Research and monitored El Reno via his twin mobile Doppler trucks, “the Weather Service doesn't need confirmation of these tornadoes. What happens with any big tornado is there's 300 chasers around it, and, well, 299 of those reports are pretty redundant.”

On that same Storm Track forum, chasers openly questioned one another's motives. The 1996 disaster on Mount Everest came up. One guy mocked a viral El Reno video in which Oklahoma-based Brandon Sullivan sits in the passenger seat of a vehicle that's getting blasted with debris, “screaming like a girl about how they're all going to die.”

In the YouTube era, close-up tornado video is valuable. That publicity, as well as payouts of up to $10,000 from media organizations for a clip like Sullivan's, is one reason chasers keep driving into harm's way. But those windfalls are rare. To truly understand the subculture that descended upon El Reno, a good place to start is with the charismatic and somewhat manic guy who made tornado chasing an extreme sport worthy of the GoPro generation: Samaras's Discovery costar, Reed Timmer.

TIMMER'S TEXTS were brief: “We'll drive through Denver at around 5–6 P.M. … and will pick u up in the tank. Bring a raincoat.” As I waited for him at the Denver airport baggage claim on June 18, sirens began screaming. A metallic voice boomed: “The National Weather Service has issued a tornado warning.… Take shelter immediately!”

I took a few steps toward the already packed restroom shelters, contemplated the irony of having never encountered a tornado until this moment, and then ran for the exit. Overhead was a swirling column of dust rising from the tarmac to the heavens. It was a beautiful LP (that's low-precipitation) EF-0 tornado that Timmer, looking at my photo after he'd pulled up in the armored Dominator 3, told me would have condensed into a funnel cloud if the humidity had been a bit higher.

Timmer, who's based in Norman, is a boyish and engaging 33, with close-cropped brown hair perennially crammed under a backward baseball cap. For roughly six years, he says, he's been working on his Ph.D. in long-term agricultural forecasting at the University of Oklahoma. According to his memoir, , he got his big break chasing the killer 1999 Moore, Oklahoma, tornado on foot while offering color commentary. Like most chasers, Timmer can recall the date, location, and EF rating of just about every tornado he's ever seen. Chasers don't talk about seeing tornadoes so much as “getting” them, which is to say possessing them like a Grateful Dead ticket stub or memorable summit photo.

In the new Dominator 3, followed by the team's GMC Yukon, we drove north. Or rather we “blasted” north, in the parlance of chaser lingo, tracking a low-pressure trough that was supposed to move across Montana and North Dakota. The Dominator, with its angular matte black exterior, looks like the offspring of a monster truck and the Batmobile. At every gas station crowds mobbed Timmer, asking the same series of questions, to which he always enthusiastically answered: It's a Ford F-350 diesel reinforced with half-inch steel armor, Kevlar, and bullet-resistant Lexan windows; it weighs 9,000 pounds; yes, it's been through an EF-3; no, there's not going to be a tornado here; and yes, take as many pictures as you want.

It soon became clear that chasing, in its essence, is a long drive with an indeterminate destination and terrible food. Racing across America's breadbasket, it's nearly impossible to purchase anything that has grown out of the ground. About the only similarity with Everest is the risk of blood clots, in this case from sitting for so long rather than from the blood-thickening effects of altitude. Several of Timmer's crew joke that they can feel them forming.

The Dominator team sleeps only in fair weather. They exist on a diet of American Spirits, Rockstar Punch, and 5-Hour Energy consumed at 45-minute intervals. They empty Gatorade jugs—and then refill them instead of stopping to relieve themselves. They talk about the weather. By 3:19 A.M., Connor McRorey, the University of Oklahoma student at the wheel, had gotten us to a Rodeway Inn in Billings, Montana. “Well, that's what stormchasing mostly is,” McRorey said. As he stepped out of the truck, he uncovered something smashed beneath his jeans. “Oh look, there's half my sandwich.”

Timmer, like Wurman (and Samaras before he died), is working on tornadogenesis, though his efforts have a decidedly more homespun feel. Instead of the million-dollar Doppler-radar trucks that Wurman uses, or the steel turtle probes Samaras designed, Timmer attempts to get his weather sensors into tornados via delivery systems that seem like schemes to escape Gilligan's Island. Though he initially had success deploying parachute probes with a 12-foot fixed-wing drone, the FAA grounded him. Now, in the back of the Dominator, there was a busted model rocket of the hobby-store variety. In a box sat half a dozen “stake probes,” which consist of weather sensors and GPS pet trackers mounted to barbed half-inch-steel pickets. Finally, there was a potato gun, which can fire a parachute probe up into a tornado's circulation. (Or a hole in the rear window of the Yukon, as it had done a few weeks back.)

“It's hard to get grants when everybody thinks you're a reckless spaz, but I'm not,” said Timmer, sounding exhausted at just past 7 A.M. the next morning. He'd been chasing nearly nonstop for three months, and the death of his colleague was weighing on him. He'd been thinking more about his parents back in Michigan.

Timmer's current fixation is suction vortices, those microfunnels that, as in El Reno, peel off from the main tornado and last for only a fraction of a second. Because they spin within the main rotation, vortices carry the mother tornado's power but also add their own. Getting hit by one might be like getting smacked with a baseball bat wielded by somebody zooming by on a freight train. Suction vortices would also explain why Samaras's Cobalt was flung a quarter-mile while other vehicles inside El Reno's circulation were merely pelted with debris.

After driving 3,000 miles in four days, we finally caught up with a cell that had “a good spin on it,” near the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in western South Dakota. As we got closer, other cars with cameras and wind-speed-measuring anemometers bolted onto them materialized out of the traffic like members of a secret society. But just as quickly, the cell went “outflow dominant,” dumping energy in the form of rain and wind instead of sucking air up.

On that empty Badlands road with post-storm easterlies whipping by, McRorey finally said the thing that seems so painfully obvious to an outsider watching tornado hunters in their element. “There is nothing else I'd rather do than chase tornados,” he said. “There's nothing that makes me as happy as seeing them.” For many, the thrill (and tedium) of the chase gives way to euphoria and awe as they watch the air organize itself into something as beautiful and powerful as a tornado.

On my final day with team Dominator, a cell in southeastern Wyoming finally produced a fleeting spin-up. Naturally, we were parked directly underneath the rotating wall cloud, which hung just a few hundred feet over our heads—a feature often called the bear's cage because the rain falls in a tight circle around a dry center, and because that's where the tornado tends to form. Todd Dalley, a pipe fitter and mechanical savant from Michigan, was aiming to get a probe into the circulation on the back of a radio-controlled quadcopter. With cameras rolling, the machine took off and briefly soared into the swirling sky. Then it did exactly what you'd expect a tiny helicopter to do in a tornado. It crashed.

Another week on the island.

IF NATURE HATES a vacuum, it loves a fight. Everybody realizes that they can't all be “doing science,” though few will actually cop to it. But Timmer and several other ego chasers, as they get labeled, make a good lightning rod. When I asked Wurman whether he considers Timmer a lightweight, his reply was blunt: “He wouldn't be considered an any-weight in tornado science. I mean, really, he's not a tornado scientist.”

In the hierarchy of stormchasers, serious scientists with grant funding form the in-crowd. These are Ph.D.'s like Wurman, his research partner, Karen Kosiba, 36, and University of Oklahoma professor Howard Bluestein, 65, all participants in the well-funded Vortex studies on tornado-genesis. Even Samaras, whose grants came from National Geographic instead of the National Science Foundation, apparently wasn't in their league. “He was a recreational chaser. He was also an engineer,” explains Wurman. “Putting a camera in a hard box and putting it in front of a tornado is not a super original idea, but Tim was able to execute that kind of thing much better than most chasers.”

Part of the guff is no doubt that reporters glom on to the most charismatic guys with the craziest footage. But here's another theory that has more to do with tornado science itself: the most significant breakthroughs have come not from institutionally sanctioned studies but from chance observations. The biggest came in 1953, near Champaign, Illinois, when a radar engineer named Donald Staggs happened to notice an odd trailing elephant-trunk shape hooking downward on his screen about the time when a tornado was reported in a passing thunderstorm.

Since Staggs's day, Doppler-radar resolution has evolved not only to see his so-called hook echo but also to measure what's referred to as the tornado vortex signature (TVS), the winds tearing past each other in opposite directions. And with the existence of nearly nationwide high-resolution Doppler coverage since 1988, the NWS can monitor hundreds of storms at once. When a TVS appears—or when a chaser calls in an actual tornado—the Weather Service can issue a warning, which prompts emergency-alert systems that now include text messages and reverse 911 calls. Despite those advances, the average tornado warning has only been extended to 15 minutes.

If history is any indicator, the next breakthrough is as likely to come from an amateur as from a pro. Going back to Benjamin Franklin—whose kite-in-a-thunderstorm stunt is often credited as the first weather experiment—meteorology has been awash in ego battles. As Lee Sandlin chronicles in his excellent history of tornado chasers, , America's first meteorologist, James Espy, pooh-poohed amateur William Redfield in the 1830s for suggesting (accurately) that tornadoes spun. In 1896, the chief tornado expert at the Weather Bureau—now the National Weather Service—was a man who was certain that tornadoes blew outward from their cores (they suck air in) and advocated creating a “tornado trap”—a giant cache of dynamite to “blow [the twister] to smithereens”—at the western edge of every town on the plains.

If scientists have had it rough trying to increase prediction times, stormchasers have been steadily improving at finding twisters. David Hoadley first started chasing in his family's blue Oldsmobile in 1956. It took him until July 6, 1962—a date he recalls like it was his wedding day—near Leola, South Dakota, to finally film a tornado. The 1990s brought the Internet, which chasers used to access real-time radar data at hundreds of local libraries across the plains. Now , a satellite-based software subscription, will display every lightning strike in a storm, while the Radar Scope app tracks the size, height, speed, and rain density of storms.

Commercial operator Martin Lisius, a.k.a. the Storm Whisperer, who founded Texas-based in 2000, witnessed the rise of chaser culture. He calls Timmer's ilk “the children of ,” referring to the 1996 Helen Hunt and Bill Paxton blockbuster that nailed the ultimate chaser dis—”He's in it for the money, not the science”—and, according to Wurman, “got a lot right.” Lisius calls the current uptick in popularity “the children of Storm Chasers.“

“Oh, I blame half of everything on Reed Timmer,” he says. Of course, this is coming from a man who takes total rookies out hunting tornadoes. But Lisius contends that stormchasing is actually not the dangerous thrill ride that the Discovery Channel has popularized. “You want to talk to somebody who has a good idea of stormchasing?” Lisius said. “That's me.” So I signed up for one of his tours.

IF YOU LISTEN to the media hype in tornado country, a surge of commercial tour groups are clogging the roads like Yellowstone visitors gaping at bison. The part about the surge is true. Since Lisius started Tempest, dozens of outfits have cropped up, including and , partly owned by Timmer. But anybody who spends 20 minutes in one of these vans can tell you that the part about clogging the roadways is false.

The profile of a commercial stormchase client is about what you'd expect on a birding safari. My group consisted of five middle-aged women, most of them there to learn from landscape photographer Camille Seaman, who's been working on a ten-year project called The Big Cloud. Lisius himself wasn't on the tour, which was led by 55-year-old California meteorologist Bill Reid, who is quiet and serious and wrote much of his master's thesis on why the record high of 134 degrees set in Death Valley in 1913 was almost certainly a bogus reading. Like most hard-bitten chasers, Reid has arranged his life around the weather, working part-time at an Albertsons.

Over the course of a week, we drove some 3,800 miles across Colorado, Nebraska, Kansas, and Iowa, and into New Mexico. Even with a fair-weather-inducing high-pressure system hanging over the country's midsection, we saw thunderstorms that produced 80-mile-per-hour straight-line winds, swirling super-cells dragging sweeps of rain, and lightning that would rival any Independence Day cannonade. Four of the women were just interested in taking photos of dramatic skies. The fifth, a woman in her sixties named Gwen, confided that she wanted to get really close to a tornado and wondered if Reed Timmer might let her ride along in the Dominator.

If I started out as a tornado-tourism skeptic, I left convinced that it's a worthwhile enterprise. The guides keep a safe distance from their quarry and haven't killed anybody in more than a decade of operation. It's also highly educational. On any given day in the U.S., there's a once-in-a-lifetime weather event. If you're willing to drive 500 miles, you can probably witness it. And what you'll see is a general population blithely unaware of signs like anvil clouds and rain shafts until their cars and homes are engulfed by wind or hail. Spend one week chasing with a patient teacher like Reid and you'll never look at the sky the same way again. Nor will you be caught in a freak storm. Those don't exist.

As Reid explains, the storm is always there in the data, even before it's a giant anvil-shaped thunderhead. When the dew points and high temperatures converge, the sky starts to look “juicy.” Add heat from the sun and pretty soon a field of puffball-like cumulus clouds starts to form. Add more heat and Reid will notice that a few of the “Cu” clouds, as they're noted on weather maps, are looking “perky,” then “beefy.” Finally, they're sending up towers as a genuine updraft.

Each morning, Reid held a weather briefing, projecting charts onto a motel-room wall. In the simplest terms, a thunderstorm is just a giant updraft sucking in moisture as what's called inflow. If the air is hot enough, the updraft will break through the inversion, called the cap, which typically sits a few thousand feet off the ground, and blast all the way to the stratosphere, where it flattens out into the anvil top of a cumulonimbus cloud. If conditions are right, with cold, high-altitude jet-stream winds coming out of the northwest and warm surface winds coming out of the southeast, the cell will develop a spin. Weather people call this a supercell and the swirling updraft within it a mesocyclone. But it's still not a tornado yet.

As the spinning updraft peaks in intensity—usually in late afternoon, when the earth is at its hottest—a wall cloud might descend from the storm base. The lower the base, the less room air has to enter the updraft, so it accelerates, forming a tornado vortex. Finally, as the afternoon cools, the storm will release its rain and wind on the land in a giant sigh of outflow energy.

Our group saw half a dozen supercells and one thunderstorm in Kansas that toppled tractor-trailers. At each stop, having guided us into ideal viewing position, Reid would deadpan, “Enjoy your storm.” Gwen, a community-college ESL teacher in Santa Barbara, California, often lingered after Reid shouted that it was time to move. She didn't get to see her tornado, but she'll be back.

EL RENO FORMED as a tail-end Charlie cell, a term borrowed from World War II bomber pilots to mean the last in the formation. As the southernmost storm in the line, it had no competition for the warm, moist air below it. And so it grew, and all of chaserdom—Timmer, Wurman, Samaras, Hoadley, Reid, and hundreds of others, along with their enthusiasm, egos, baggage, and restraint—was there to meet it with the kind of certainty that could make you believe a powerful tornado was not just likely but scheduled.

Wurman and Kosiba were in line to board a United flight out of Wichita, Kansas, at just past 6 A.M. But the forecast looked promising, so the pair rejoined their chase team and headed south.

At the NWS's office in Norman, Rick Smith, the meteorologist who coordinates warnings, was already concerned. That afternoon, at 3:30, his agency issued a tornado watch that included a PDS note, which stands for “particularly dangerous situation”—a “rare set of ingredients,” says Smith, for storms with “the potential to be big and bad and long lasting.”

Samaras was heading south toward Canadian County when he issued his final tweet, at 4:50 P.M. “Storms now initiating south of Watonga along triple point. Dangerous day ahead for OK—stay weather savvy!”

At just before 4 P.M., Tom Magnuson, the warning-coordination meteorologist for the NWS's Pueblo, Colorado, office, was aboard Frontier Airlines flight 231, en route from Nashville to Denver. As the plane passed over central Oklahoma, he looked out the left-side window. “I saw what's called an overshooting top,” he recalls. “That's where the updraft goes up into the stratosphere.” Normally, the anvil cloud spreads out along the bottom of the stratosphere, but in big storms the updraft can be so powerful that it bulges straight through. Radar echoes show the El Reno storm topping out at 65,000 feet.

“I had never seen anything like that from an aircraft,” says Magnuson. “My first thought, to be honest with you, was people are going to die down there.”

Oklahoma City's KFOR meteorologist, Magic Mike Morgan, had the same thought. “You either need to be out of the way or below-ground,” he told viewers at 6:30, adding, “You've gotta go south and you need to go now,” which was interpreted as an evacuation order by many people. Whether his warning was to blame for some of the traffic seems moot: much of the city was already clearing out for the summer weekend.

Despite there being up to 300 chasers in the El Reno area, nobody reported seeing the Twistex crew. That's probably because they were driving the Cobalt instead of their large, customized Chevy pickup; they'd left that behind in Kansas, where they were working on a lightning research project. At 5:36, Rick Smith's NWS team issued their first tornado warning, which triggered the emergency-broadcast system. At 6:03, what looked like a series of fleeting tornadoes began touching down west of El Reno. Timmer and his Dominator crew were a quarter-mile north. “We saw suction vortices spinning around at a rapid rate,” says Timmer. Except that these were the size of fully formed tornadoes.

Wurman's group was still well east of the storm, but their radar produced stunning images of its complex structure. As a vortex would briefly form and then vanish, Wurman's radar reading would spike to nearly 300 mph, twice the main storm's 150-mph winds. Chaser videos dramatically confirmed this. In one clip, a billboard on I-40 seems to vaporize for no reason, exploding like it was hit by a death ray.

Then the storm did something odd. The 2.6-mile-wide cyclone cloud descended and in under a minute planted itself on the ground. Just as quickly, it was obscured by rain. None of the chasers saw it accelerate, expand, and suddenly zag northeast.

Half a mile to the west, on the shoulder of Highway 81, Weather Channel meteorologist Mike Bettes was just going live. In the footage from that day, you can see him examine the storm, glowing ice blue with hail, before suddenly having a frightening realization: “That's it! Right there! There's the tornado!” Bettes and his crew piled in and sped south, cameras still rolling, capturing the twister's outer ring as it bore down on them. “We have to go faster,” Bettes shouted to driver Austin Anderson. “Go as fast as you can!” Seconds later, the car lofted into weightlessness. “Hold on, brothers. Hold on,” Bettes yelled. The team's camera was ejected from the window but miraculously captured their Tornado Hunt vehicle tumbling through a field. Bettes's car was the second of three in the Weather Channel caravan, but the other two stayed on the road.

At that point, Timmer and the Dominator were trying to get back in the chase. But just as they turned north, they plowed into a tangle of downed power lines. The driver gunned the engine in reverse, but the lines had hooked over a light bar and whipped the hood off the car like a slingshot. Their chase was over. They headed down Highway 81, where they encountered Bettes and Anderson surveying the damage. Anderson didn't realize it at the time, but as the car tumbled, he had fractured several vertebrae and ribs, along with his sternum.

THERE WERE MANY chasers in El Reno who got a bad vibe and played it safe. Once the tornado became obscured by rain, Hoadley and others abandoned the chase. Camille Seaman, a Shinnecock Indian, had seen an owl fly over their van, which, she told the group, meant someone was going to die. Wurman never got closer than two miles. But the scene across that part of Oklahoma was almost as scary as the twister itself.

“It was crazy,” says Wurman. “These intersections were essentially out of control, and people were just panicking. It was like one of these zombie apocalypse movies. People were banging on our windows, insisting that we tell them where the tornado was and how to get to safety.” At one point, a Porta-Potty flew by.

Farther west on I-40, state trooper Betsy Randolph was pulled off the road. “I heard troopers on the radio talking about how the tornado had just come through an area,” she said. “And then you could hear one scream to the other, 'There's one right behind you! Run! Run!' ” One trooper drove beneath an overpass, and when his car got stuck, he got out and lay in a ditch. The car was totaled by debris; the trooper survived.

Local amateur chaser Richard “Pup” Henderson, 33, wasn't so lucky. A truck driver who'd followed tornadoes with a news crew on a few occasions, Henderson snapped a cell-phone photo of the twister that moments later would kill him.

For months after the storm, there was speculation about what had happened to Samaras's team. “If you said who's the most cautious guy out there,” remarked Bettes in a Weather Channel special, “all the hands in the room would go up and say it's Tim.” Still, his memoir boasts of having planted a probe only 82 seconds and 100 yards ahead of an EF-4 monster in 2003.

But theories that Samaras was caught in a chaser traffic jam never panned out. “They were right behind me at Highway 81,” says Dan Robinson, whose rear-facing dashcam on his Toyota Yaris captured the last images of the white Chevy Cobalt. According to the time stamp on the footage, the Samarases, with Carl Young at the wheel, crossed Highway 81 at 6:19 P.M. At that point, the tornado was still moving southeast. “There was no concern at all,” Robinson says. But just 30 seconds later, that changed. “I started seeing the rain curtains approaching the road from the south.”

Robinson, who moved to St. Louis from West Virginia eight years ago to chase storms full-time, saw immediately that the storm was now angling toward him. He mashed the accelerator, bringing the Yaris up to 43 mph, fishtailing on the washboard gravel road and blowing through three stop signs.

In the video, the headlights of the Cobalt fade into the rain about a half-mile back. You can see the main funnel, still only a few hundred yards wide, churn to the southeast, and a patch of sky opens up above the Cobalt. But within 30 seconds, that patch disappears and the entire storm has dropped to the ground. It was at this point, meteorologists believe, that the tornado reached maximum width and intensity. According to Rick Smith, the whole supercell accelerated briefly to 50 mph. The four-cylinder Cobalt, loaded down with three men and a trunkful of steel tornado probes, was pushing against an inflow headwind of 60 to 80 mph. It simply couldn't go faster than the storm. The tornado planted on top of them, and a suction vortex very likely sent the car tumbling with enough centrifugal force to eject two of the three men.

THAT SUNDAY, a crew of local storm-chasers, including several from Timmer's group, collected debris from around the wreckage. Among the items that ended up on a tarp in Timmer's office was a mud-caked Canon DSLR camera. It belonged to Young, but the recording cuts out well before the Twistex team's final moments. Nor did Paul Samaras's Canon C-100 camera, which was also recovered, shed any light on what happened.

As tragic as those deaths are, they shouldn't be surprising. Unlike the tour groups and recreational chasers, Tim Samaras, like Timmer and a few others, was constantly attempting to get as close to tornadoes as possible. He had safely put himself in the paths of hundreds of them. But with enough exposure to risk, eventually something very rare, like a 2.6-mile-wide storm planting itself on top of you, can happen.

Still, in 50 years, these are the first chaser deaths. The most dangerous thing stormchasers face may not be wind or even lightning but other drivers. In 2012, chaser Andy Gabrielson was hit head-on by a wrong-way drunk driver in Oklahoma and killed.

Ultimately, the 2013 tornado season will be remembered as a nasty one, though there were far fewer twisters than the average 1,250 the U.S. sees each year. FEMA estimates that last spring's tornadoes will cost insurers and taxpayers $2 billion, although, ironically, the El Reno system dropped enough rain to punch a doughnut hole of normalcy right through Oklahoma's drought. This year, 45 people died in tornadoes. Four were chasers: Tim and Paul Samaras, Carl Young, and Richard Henderson, the local amateur.

The memorial service for Henderson filled Hinton's high school gym. At a ranch rodeo the following week, his sons led his saddle horse out into the ring with his empty boots in the stirrups. Henderson's youngest son, Wyatt Wade, seven, used pieces of timber to make a cross that his stepfather helped him plant in the yard.

Doug Gerten has been cleaning up his farm, too. “We're so used to helping everybody through their difficulties,” he says. “When you become a victim, it's overwhelming.” The shop wasn't insured, but that won't stop him. “I saved up and built it once,” he says, and then pauses. “I guess I can do it again.”