This Man Is Greenpeace’s Best Hope

Human-rights superhero Kumi Naidoo has a tough assignment: lead the organization into 21st-century relevance. But after a year that saw activists lionized (imprisoned in Putin's jails) and then vilified (unfurling a banner on Peru's ancient Nazca lines), can he save the day?

New perk: Easily find new routes and hidden gems, upcoming running events, and more near you. Your weekly Local Running Newsletter has everything you need to lace up! .

A Romanian, a German, and a South African hailed a cab. It was around 11 p.m. on a cool night last September in Manhattan, and the men were planning to make a video. They all worked for Greenpeace, the international environmental nonprofit, but had little in common besides that. The Romanian was , a 33-year-old communications specialist who’d joined Greenpeace after burning out on a D.C. desk job and spending a couple of years working to protect mountain gorillas in the Congo. The German, 46-year-old Wolfgang Sadik, was a lifer; he’d been with the organization for 25 years. He helped run the actions team, the cloak-and-dagger unit that does the planning when, say, an oil rig needs scaling. The South African was the boss, Greenpeace International executive director . A tall, lanky, former human-rights activist with a kind manner, a gray-flecked beard, and an ever present African shirt, 50-year-old Naidoo is the organization’s public face.

The men were in New York City for the , a meeting of 100 heads of state billed as the next major stage in international efforts to tackle global warming. Naidoo was excited about the previous day’s march, in which nearly 400,000 people filled the streets of Manhattan, but no one was particularly optimistic about the UN gathering itself. Earlier that day, appearing on a panel at the 92nd Street Y with founder and rockers turned activists Linkin Park, Naidoo had called it “verbal masturbation.”

So he, Dumitrascu, Sadik, and a few others were going to apply pressure. The plan was to shoot a short social-media video of Naidoo calling for governments to enact clean-energy policy and, as he intoned in his deep baritone, “Listen to the people, not the polluters!” Later, at about 3 a.m., Sadik and a team would project that phrase onto one face of the UN building, on Manhattan’s East Side, in several languages. The stunt was illegal but not dangerous, so Naidoo had only just been told the day before.

“The actions are often done on a need-to-know basis,” he told me as the cab rolled along. “Most actions, I won’t be consulted about it. But if it’s something where it could be prison time or a very big court case, then they’ll come to me and say, ‘We are doing this action, it requires so much of the activists, the legal assessment is this, the worst-case scenario is this.’ And I’ve never said no. Because our people are competent.”

[quote]“The way I see it,” Naidoo says, “addressing climate change is more important than all the injustices we’ve fought over time put together. Colonialism, slavery, apartheid. This is about survival.”[/quote]

Naidoo is Greenpeace’s great hope. He spent his teenage years fighting apartheid in South Africa, buried too many friends, went into exile, and later rose to prominence in the international human-rights world. Greenpeace , when the organization was having what could gently be called a crisis of relevance. At one time the most powerful direct-action group on earth, it was trapped in a frustrating phase. With about 2,500 employees spread across 41 offices around the world, Greenpeace was too big to play the underdog, but it was still weighed down by institutional nostalgia for its scrappy no-nukes days. Since taking over in 2009, Naidoo has driven an ambitious plan to turn Greenpeace from a top-down, European NGO—its headquarters are in Amsterdam—to a decentralized, quasi-guerrilla outfit with a powerful presence in the places where, he believes, the climate war will be won or lost: Africa, Asia, and South America.

We hopped out at 41st Street, where three more members of the team waited by a balcony overlooking the East River. As a cameraman prepped Naidoo, I walked off to the side with Sadik. He had a big, well-coiffed sweep of silver hair, a mustache and soul patch, and large, probing eyes. He told me that when he was 16, his buddies wanted to join a protest against a power plant, but his father, who didn’t like hippies or radicals, said he couldn’t go. So he went. “It was wintertime, and I came at night to a secret group in the forest,” Sadik recalled. “They said, ‘We are with Greenpeace.’ ” He knew then what he needed to do with his life. “I wanted to feel politics with my senses,” he told me. “That’s why I always specialized in actions.” Sadik did graduate work in archaeology at the University of Vienna but later came back to the Greenpeace fold. “Now,” he said, “I’m saving future and past.”

Naidoo finished speaking to the camera and began walking back to his hotel, leaving Sadik and the team to deal with the projection. As I watched all this, I was struck by an obvious flaw in the plan: Who would be walking by the UN at 3 a.m.? The whole thing seemed quaint and also kind of funny.

That is, it seemed funny until two months later, when an action in Peru backfired spectacularly and Naidoo was desperately trying to save Greenpeace’s reputation after the worst gaffe in its 43-year history. At that point, I thought back to the last thing he’d said that night in New York, an offhand joke as he walked away: “Don’t wake me up if you get arrested!”

Here’s what happened: In early December, a group of 20 Greenpeace activists from seven countries, including Argentina, Chile, and Germany, traveled about six hours south from Lima. Argentine Associated Press photographer Rodrigo Abd and Herbert Villarraga, a Colombian videographer for Reuters, accompanied them. They had all come to Peru for , a multinational climate conference designed to pave the way for a binding agreement on carbon emissions, and they had secretly planned an action.

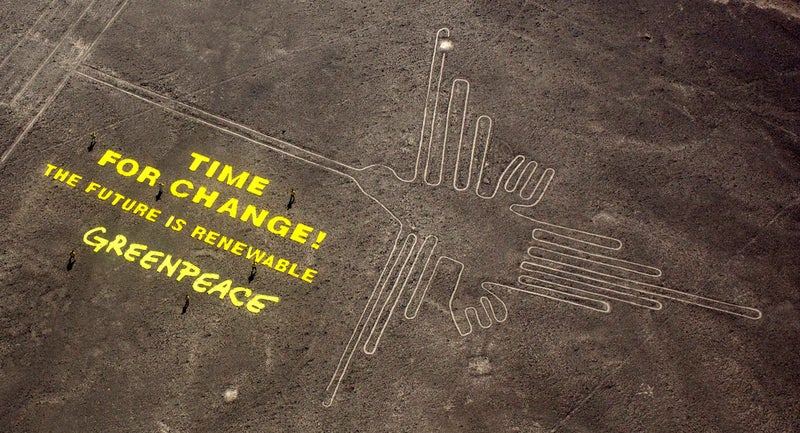

Their destination was the Nazca Lines, one of Peru’s most sacred sites. Starting around 500 B.C., the Nazca people, who lived in a nearby river valley, created hundreds of giant geoglyphs—trapezoids, a dog, a hummingbird, a pelican more than 900 feet long—by removing reddish brown surface rocks to expose the light soil beneath. Some scholars think they were religious symbols; others believe they were used to chart the seasons. The Nazca themselves were gone by 750 A.D., seemingly done in by vicious El Niño flooding exacerbated by their own agricultural clear-cutting. But because the Nazca Desert receives little rain and less wind, the lines have survived. A Unesco World Heritage site, they are a popular fly-over destination for tourists and aerial photographers. The hummingbird graces one of Peru’s most common coins.

In the predawn hours of December 8, the activists walked about half a mile from a dirt road to one of the most easily accessible symbols, the hummingbird. They carried backpacks, coolers of water, and a drone. As the sun rose, they spelling out

TIME

FOR CHANGE!

THE FUTURE IS RENEWABLE

GREENPEACE

under the bird’s beak. According to a published a week after the incident, one activist, who appeared to be running things, told the others to be careful not to step on the lines. The story identified him as Wolfgang Sadik. In a , Sadik says, “We chose the Nazca Lines because we think that these lines are a symbol of climate change. What happened here in the past on a smaller scale happens now on a global scale, and the Nazca culture disappeared because of climate change.”

The previous day, Greenpeace activists had posted footage of a similar message created at Machu Picchu. But Nazca is a more vulnerable place, and the moment the images went up on Twitter, the public attacked. Conservative media in Peru denounced the act as a violation of cultural heritage, and news outlets from the BBC to NBC followed. The activists had committed a grave insult by entering the site, which is off-limits to visitors without a guide and special footwear. Worse, the offenders left marks in the soil—their tracks and an imprint of the letter C—that, Peruvian officials allege, can’t be erased.

The day after the action, the Nazca branch of La Fiscalia, Peru’s federal prosecuting office, opened a preliminary investigation, a precursor to formal charges. But all 20 activists had left the country before any travel restrictions were put in place. Greenpeace went into damage control. The top brass claimed they had no advance knowledge of the action, and spokespeople issued anodyne apologies, including an understatement of the year: “.” Greenpeace refused to release the activists’ names, a radical departure for an organization built on claiming credit for civil disobedience.

Like the rest of the leadership, Naidoo claimed ignorance. On December 8, he was in the Philippines, delivering solar chargers to victims of Typhoon Hagupit. That morning, before the uproar, his Twitter account retweeted an image of the Nazca stunt to his 30,000 followers, but Naidoo says he wasn’t behind the tweet—Greenpeace’s communications department helps manage his feed. Naidoo says he first heard what happened on his way to the airport in Manila to board a flight to Amsterdam. When the plane landed, his voice mail was full. He slept for six hours, then booked a flight to Lima. He arrived to find news teams waiting.

“This is not what we stand for,” he . “This is not what I stand for.” When he walked out of a Nazca court after a preliminary hearing the following week, people threw eggs. “Watch out at the Taj Mahal, watch out at the pyramids in Egypt,” . “Because we all face the threat that Greenpeace could attack any of humanity’s historical heritage.” The group’s Facebook page filled with profane invective. Canvassers in the U.S. were harassed. “In 35 years of activism,” Naidoo told me, “there has never been a moment when I’ve felt so ashamed.”

The Nazca fiasco was raw meat for the large segment of the public that tends to think of environmentalists in general—and Greenpeace specifically—as strident or out of touch. It also surprised many, because Greenpeace has undergone a profound shift under Naidoo’s leadership. Before he was hired, the group was seen by many as too stunt oriented, northern (read: white and a little naive), hungry for credit, and smug—in short, the kind of outfit that might have unfurled a dumb slogan at the Nazca Lines. But in the past five years, Greenpeace dramatically increased its standing among environmental and business leaders alike by making a shrewd double move.

Most visibly, it has returned to classic, bold direct action. At the same time, it has reinvented itself as a pragmatic, behind-the-scenes organization that can dramatically influence large corporations’ global supply chains, convincing companies like Coca-Cola, for example, to . Last October, two months before Nazca, I spoke with , CEO of the , who said, “Under Kumi’s leadership, Greenpeace is less focused on flamboyant campaigns and more focused on getting things accomplished in the field.”

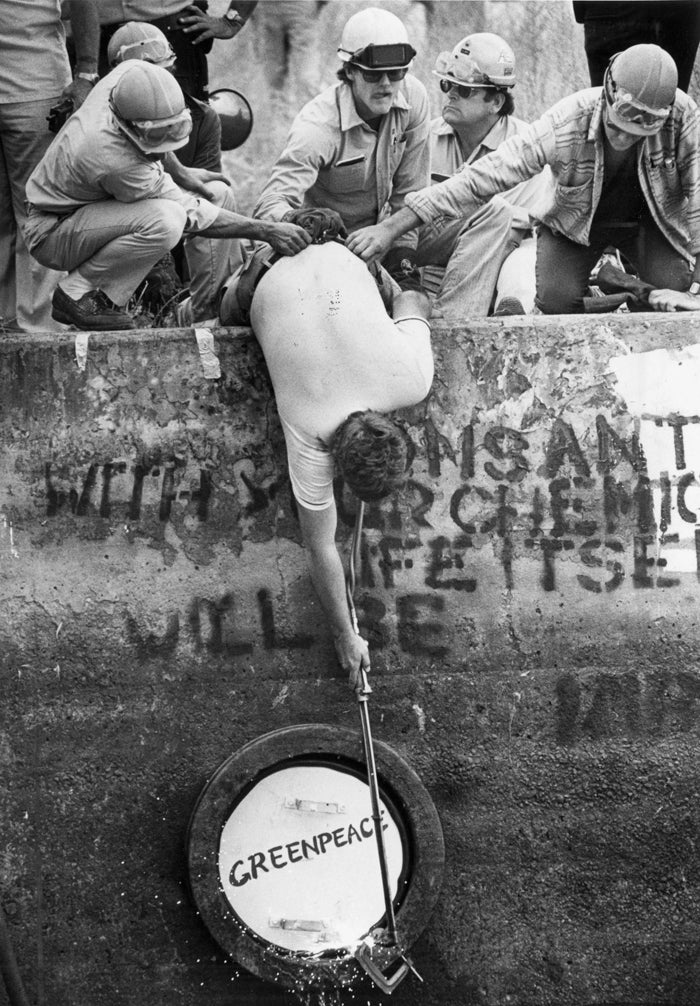

Greenpeace was built on flamboyance. The organization was founded in 1972 in Vancouver, British Columbia, by would-be revolutionaries who called themselves “hobbits.” The year before, when the U.S. government had planned a nuclear-bomb test at the Aleutian island of Amchitka, 11 protestors . They didn’t stop the test, but they did launch a movement that would endure. Greenpeace picked and won big fights by relying on a simple formula: find someone harming the environment, confront them with cameras rolling, and use publicity to generate outrage. There were bumps along the way—notably, the 1985 by French foreign-intelligence operatives in New Zealand—but during its first two decades, Greenpeace was arguably the most effective activist operation in history. It created a generation of antiwhaling and antinuclear activists, and gave donor-funded antiestablishment environmentalism a face.

Starting in the nineties, Greenpeace tried to paint itself as a policy influencer, ceding direct fights to groups like and . Sea Shepherd’s leader, , a Greenpeace cofounder turned vociferous critic, has become a household name, thanks to Whale Wars, the popular reality-TV series about direct action against Japanese whalers. Around 2005, Greenpeace started targeting corporations, taking on companies like McDonald’s over . Still, its influence waned; it was too extremist for corporations and not tough enough for other environmentalists.

Naidoo was hired to perform a brand rescue. He focused on a few key climate issues, like Arctic oil drilling and deforestation in Asia and the Amazon. He also pushed for an ambitious restructuring to move people and money away from traditional European environmental strongholds to places like China, Brazil, and India.

The shift south and east has caused some turmoil in the ranks, but it has also been seen as forward-thinking as other NGOs make similar moves. “All of us big international organizations that have our roots in North America and Europe have to change,” says Samantha Smith, director of global climate and energy initiatives at the . “We’re not winning the fights we need to win. If you can’t credibly speak to the concerns of developing countries about getting people out of poverty while also getting off coal, you’re not going to be effective.”

But it’s the return to civil disobedience that has raised Greenpeace’s public profile the most. In 2011, Naidoo when he scaled an oil rig off the coast of Greenland. Two years later, in September 2013, 28 Greenpeace activists protesting Arctic drilling, along with a photographer and videographer, were off the Russian coast. Some of the group were climbing an oil platform when a helicopter materialized overhead, dropping balaclava-clad Russian troops armed with machine guns onto the deck of their icebreaker, the Arctic Sunrise. The activists were charged with piracy (later lessened to hooliganism) and threatened with 15 years in prison. For nearly three months, the so-called languished in primitive, freezing jails. Naidoo offered to trade places with them, and 11 Nobel Prize winners wrote to Russian president Vladimir Putin, asking that the charges be dropped. German chancellor Angela Merkel and New Zealand prime minister John Key chimed in, and even Watson had to praise his old outfit. “It appears that Greenpeace has sparked a new cold war,” he wrote on his Facebook page. Nearly four months after the arrest, on the eve of the Sochi Olympics, Russia . Greenpeace, it seemed, was back.

On the surface, Greenpeace and Naidoo aren’t an obvious match. He grew up in a poor township outside Durban, the second of four children in a family descended from Indian indentured servants. But Kumi and his siblings never felt poor, even when they attended an elementary school that lacked electricity. His mother, Mana, sewed clothing for neighbors, and his father, Shunmugam, was a bookkeeper. “We have enough,” Mana would tell the kids. A picture of Mahatma Gandhi hung on a wall in the family home.

In June of 1976, when Kumi was ten, thousands of black students gathered in Soweto—the famous township near Johannesburg—to protest the government’s decree that Afrikaans would be a compulsory language in public schools. Police opened fire, killing hundreds. The Naidoo kids were only vaguely aware of the violence. “I clearly remember our teachers telling us we were privileged because we were top students, and we would get out of the township,” says Kumi’s younger brother, Kovin, now a leading optometrist in South Africa.

In 1980, this optimism crashed down in a sudden stroke when Mana committed suicide. Kumi, who was 15, briefly sought refuge in alcohol, getting tanked and falling asleep on park benches. Then he and Kovin threw themselves into the student protest movement, taking part in dangerous clashes with police. Kumi has often asked himself whether his mother’s death pushed him to the front lines. “If she had been alive,” he says, “would I have had the courage? I always wonder.”

Kumi and Kovin were expelled from high school for their roles in the marches. The principal called Shunmugam and told him to pick up his sons. Shunmugam replied that the boys could walk and hung up. Shortly after that, sensing the potential for more trouble, he took the boys’ passports and hid them.

In 1983, Kumi enrolled at the University of Durban-Westville, where he studied politics. He and Kovin soon joined the —an illegal act, since the party had been forced underground—working in different cells. Kumi helped lead the ANC’s student group and also organized for the armed revolutionary branch, recruiting and distributing illegal literature. He told me he never took part in any violence, an assertion that a half-dozen sources in South Africa back up. “I was so high-profile in the mass movement,” he says. “They were bugging our phone. So I was never put under pressure to join the armed struggle.”

Still, Naidoo says, it was a different time with a different moral code, and he spent most of his weekends at the funerals of friends killed by police. In December 1986, he was awarded a Rhodes scholarship to study political philosophy at Oxford University. By then, however, Naidoo’s ANC cell had been compromised and he was on the run, hiding in friends’ houses. Soon after the Rhodes news, the police came to his dad’s house late at night, threatening to kill Kumi if they caught him. Another night, he snuck back home and Shunmugam gave him his passport. The next spring, to avoid a court summons that he was convinced would lead to his imprisonment and torture, he had some doctor friends admit him to a hospital, where they administered a placebo IV. He was discharged just before the court sent police racing over.

But before Naidoo could flee to England, he still had to take his exams. So he asked a friend, prominent playwright Ronnie Govender, to design a disguise. “He said, ‘We’re going with the Lionel Richie,’ ” Naidoo recalls. The young activist got a perm, shaved his beard, and walked around unmolested while finishing his exams with the help of a sympathetic professor. Close friends couldn’t recognize him. He made it to England and was just a year into his Ph.D. studies, in June 1988, when Kovin was arrested and thrown into solitary confinement for eight months.

In 1990, the ANC was unbanned and Nelson Mandela was released from prison. Naidoo returned to South Africa to help establish the ANC as a legitimate party, then trained electoral staff for the country’s first democratic election, in 1994, when Mandela became president. It wasn’t long before he saw his comrades taking lucrative jobs or entering politics. “People like me became marketable,” he says. “I jokingly said the term NGO no longer stands for nongovernmental organization, but next governmental official.”

He founded an umbrella group for South African NGOs, then joined , a small human-rights organization that punched way above its weight. He soon found himself fielding invites to talk at venues like the World Economic Forum, in Davos. His many fans from the international NGO circuit point to one standout trait: his humility. “When he comes in and speaks, he’s speaking on behalf of a lot of people,” says Cynthia Ryan, a trustee of the , which funds human-rights and security initiatives. “He’s very aware of that.”

Naidoo started tuning in to environmental issues in part through his daughter, Naomi. (He has never married; Naomi’s mother is a friend from Oxford.) In 2008, he joined Greenpeace Africa as a board member. In 2009, , the chairman of Greenpeace’s board, called. At the time, environmental NGOs were starting to look south and east while moving away from nature-centric strategies and toward a vision that accounted for human wellbeing. Greenpeace, meanwhile, was caught largely in the past. “They needed to bring relevance to an organization that many saw as increasingly irrelevant,” says , executive vice president of . But Naidoo was 19 days into a hunger strike to protest the humanitarian crisis in Zimbabwe.

“Thank you very much,” he said. “But I’m afraid it’s bad timing.”

That night he spoke about it with Naomi. “Dad,” she said, “if you don’t consider this, I’ll never speak to you again.”

So he took the job.

Greenpeace has an annual budget of about $330 million, all of which comes from individual donors or foundations; it doesn’t accept corporate contributions. That’s roughly $200 million more than Conservation International’s annual operating cost, but $300 million less than the World Wildlife Fund’s and $400 million less than the Nature Conservancy’s. Naidoo doesn’t wield the influence that the Nature Conservancy’s Tercek or Conservation International CEO Peter Seligmann do. He can’t preserve small Edens with the stroke of a pen. His compensation is also lower: Naidoo makes about $150,000—around a quarter of what Tercek does.

But Greenpeace’s resources are used in a way that gives Naidoo a singular power, one that is particularly scary if you’re the CEO of a multinational corporation. Greenpeace spends about $100 million a year on campaigns and media outreach, much of which is aimed at attacking specific brands. These days it pays to be seen as a Greenpeace ally—or, more specifically, to avoid being seen as a Greenpeace foe.

I saw this firsthand at the climate summit in New York, where executives from Asia Pulp and Paper pulled Naidoo aside for a photo op. In 2011, Greenpeace targeted the toy company Mattel over its use of packaging from APP, which was clear-cutting Indonesian rainforests. It first tried to convince Mattel to change its supply chain. When Mattel didn’t, Greenpeace’s social-media team in which Barbie gets dumped by Ken. In the spot, an unnamed whistle-blower shows Ken a video of Barbie chainsawing orangutan habitat. Ken yells, “It’s over! That fucking bitch!” After receiving 500,000 e-mails, Mattel dropped APP.

Other successful campaigns have targeted Nestlé, for its , and Facebook, for its . (The latter campaign was coordinated on Facebook.) Last year, Greenpeace for its reported $116 million partnership with Shell, the Arctic-dreaming oil giant. Lego resisted an initial protest, in which Greenpeace activists dressed as Lego figures showed up at the company’s flagship store in New York City. But in July, a video showing toy figures drowning in oil went viral. Six million people read the words “Shell is poisoning our kids’ imaginations.” As a result, Lego agreed to stop selling Shell-branded toy race cars.

Business executives I spoke with portrayed Naidoo as a shrewd, pragmatic negotiator who would rather implement change behind the scenes than twist a public knife. “He’s not an extremist,” says Paul Polman, CEO of Unilever, which was persuaded by Greenpeace to ditch hydrofluorocarbons, a greenhouse gas used in refrigerants. “It’s not always Greenpeace’s way or the highway. It helps with these discussions to take the emotion out of it, and Kumi should be credited with that.”

To Sea Shepherd’s Paul Watson, this is called selling out. “They’re a multinational eco-business,” he likes to say. “The have a ship that goes around fundraising, and they make money from people’s genuine concern.” He also told me, “Kumi’s not really an environmentalist. He came from a human-rights background. What did change since Kumi came in is that Greenpeace isn’t doing as many campaigns.”

Greenpeace would readily agree that its focus is increasingly multinational. The plan for the shift to developing countries—the “new operating model,” as it’s called internally—was first raised by Naidoo’s predecessor, a German scientist named Gerd Leipold. But Naidoo, who is at heart a community organizer, has made it a defining cause.

“We don’t win if we don’t win in the countries with significant population sizes in the global south,” says Naidoo. “Even if everyone else says, ‘We’ll do the right thing,’ if China, Brazil, African countries, and India go for a carbon-intensive economy, we will lose.”

Under the system, scheduled to be finalized by the end of the year, all 40 of Greenpeace’s national chapters will pool their funds. Areas like Asia, Africa, Brazil, and the U.S. (important because of its energy consumption) will receive the lion’s share of the money, while big fundraising countries like Germany and the Netherlands will sacrifice. Nearly 70 of the 250 jobs in Amsterdam will move overseas, a process that’s already begun.

Campaigns in the global south and east take many forms. Some are feel-good, like the 2010 effort to in rural South Africa so people could watch the World Cup. Some are contentious: last year, the Indian government and arrested two of its activists in a heated battle over a proposed coal mine. Some are still fuzzy: in China, where civil disobedience is about as welcome as Free Tibet stickers, Greenpeace has focused on legal campaigns and awareness-raising art— and a powerful about smog by a Chinese director. Some can be dangerous: in 2010, in Indonesia, and someone hung an effigy of Naidoo outside the Jakarta office in 2012.

And some are pretty boring: in Cameroon, Greenpeace has about a New York agriculture firm that wants to clear forests to produce palm oil. The idea is not to claim credit but to educate locals so they’re better prepared next time. “Kumi is encouraging people to look at issues more systemically,” says , the U.S. director. “The environment is deeply connected to all these other issues: economic injustice, racism, problems with neoliberal economies. That is a deeper analysis than ‘You have to save the forests,’ and I appreciate that.”

Another U.S. staffer put it more succinctly: “He’s helping privileged environmentalists pull our heads out of our asses.”

Still, the master plan has created friction. Last summer, the European press, which covers Greenpeace closely, erupted when one of the group’s financial officers speculating on international markets. Then Naidoo’s second in command, Pascal Husting, was outed for commuting regularly to Amsterdam from his home in Luxembourg by plane. Forty-three members of the Netherlands office called for Husting to resign. Naidoo apologized and Husting kept his job, though .

“This was hugely sensitive,” says , the director of that office. “I’m not sure Kumi and Pascal understood the reputation risks in the Netherlands on this.” Borren is a firm supporter of Naidoo’s changes. “There are still a lot of people who want Greenpeace mostly how it was—David and Goliath,” she told me. “We’re not in that space anymore. I’m not a hippie. We’re a major organization, and we need to get more professional.”

In the aftermath of the Nazca stunt, some observers raised their eyebrows at the notion that Greenpeace’s leaders were ignorant of the plan. “There can be no doubt that Kumi knew of the stunt beforehand,” Paul Watson wrote on Facebook. “And if he did not, he should resign for the incompetence of not knowing that this action would take place.”

There was also plenty of anger within the organization itself. Greenpeace code stipulates that activists take responsibility for their civil disobedience, but the Nazca 20 fled. It looked cowardly. “We don’t do that,” said one U.S. staffer; another told me, “I want to know who needs to be told to leave.”

“This activity was completely in violation of Greenpeace values,” Naidoo said. The situation put the organization’s leaders in a bind: normally, Greenpeace takes pride in protecting its activists by paying for legal fees and attracting media attention. Now they were in the sticky situation of condemning the action publicly but refusing to name those responsible out of fear of legal repercussions.

[quote]The Nazca fiasco was raw meat for the large segment of the public that tends to think of environmentalists in general—and Greenpeace specifically—as strident or out of touch.[/quote]

In December, Greenpeace . Naidoo told me then that it appeared the stunt had been organized by a single person without institutional approval. When he testified in the preliminary hearing in Nazca on December 18, he revealed the organizer’s name to Peruvian authorities. “What do you do as a leader?” he had said to me then. “On the one hand, I had to do the right thing in terms of accountability. On the other, I had to take into account that many young people in good faith relied on someone leading the process.”

He didn’t tell me the person’s name, but judging from early press reports, it wasn’t too hard to suspect Sadik. This was confirmed a few weeks later. In January, the First Court of Preliminary Investigation in Nazca —basically an arrest warrant—for Mauro Fernández, a 26-year-old Argentine who had served as spokesman on one of the videos of the stunt. Fernández, along with the AP and Reuters journalists Abd and Villarraga, were , which can carry a six-year prison term. On January 18, a visibly shaken Fernández, speaking from his home in Buenos Aires, told a Peruvian news station, “Sadik is the one who evaluates the situation and designs the activity and makes the final decision.”

Two days later, a lawyer for Greenpeace International delivered papers to prosecutors in Nazca. They contained voluntary statements from Fernández, Sadik, and two other Germans, all of whom described their roles in the action. Sadik—who, through Greenpeace, declined to speak to �����ԹϺ��� after the Nazca action—named himself as the organizer.

Naidoo rejected the idea that Greenpeace was making one person fall on his sword. “From what I’m being told,” he said, “the activists didn’t know what site they were going to beforehand. So people acted without proper information, and the person holding the information didn’t share it. It seems fair that this person should hold responsibility.”

What about the organization’s decentralized structure—did Greenpeace’s guerrilla strategies open the door for errors in judgment? “It’s not about changing the fundamentals of our approach,” Naidoo said. “This was an objective individual failure rather than an objective institutional failure.” Still, he seemed optimistic that the activists might avoid prison time. He cited precedent: in 2013, followers of the Dakar Rally, an international off-road car race, inflicted significantly more damage to the Nazca Lines and avoided punishment. That same year, with government permission, .

When I spoke with Ana Maria Cogorno, director of the nonprofit Maria Reiche Association, which is dedicated to protecting the lines, she suggested that the government was using Greenpeace to divert attention from its own unwillingness to preserve the site. “They have to blame somebody,” she said. She’s no Greenpeace fan, but she hopes that the attention might finally lead to some protections. “Greenpeace has been such a help to me!”

As of early February, no further charges had been filed. Greenpeace was wrapping up its internal investigation, Sadik was working in the Germany office, and the others were still on the payroll as well. An Argentine judge declined to detain Fernández but ordered him to stay in the country and remain near his home.

How badly the episode will damage the organization is another question. “The way it’s been presented by Greenpeace is that it was a rogue event,” , a member of the Sierra Club’s board of directors, told me. “There are very few groups that have rogue events. And anyplace you have that, it gets shut down and people get fired.”

Both Tercek, the Nature Conservancy CEO, and Sanjayan, of Conservation International, believe Greenpeace can weather this if it learns from its mistake. “I don’t think it will hurt them in fundraising,” Sanjayan says. “People who support them understand them. It’s like, ‘Yep. Par for the course. That’s Greenpeace.’ But if Kumi wants to coalesce the organization around a few key points, this does derail that. He’d do well to more strongly articulate what they want, and to build around that, because otherwise the brand is going to get diluted. I mean, think about the word, the name Greenpeace—I’m not even sure what that means.”

It means different things to different people in different places. In America its activists are seen as treehuggers. In Europe they’re keepers of a noble flame. In boardrooms they’re threats. In India they’re criminals. And in Naidoo’s mind they’re just getting started. “The way I see it,” he once told me, “addressing climate change is more important than all the injustices we’ve fought over time put together. Colonialism, slavery, apartheid, the right to vote. This is about survival. So if it was OK for people like me to be prepared to go to prison and be prepared to get killed, then surely when the very future of the existence of the species of humanity is at risk, then I think we need to be willing to take much higher risks.”

In December, Naidoo hinted to me that plans for more actions were in the works, things that might replace Nazca in the news cycle. But not everything fades. Look at an aerial image of the Nazca hummingbird now and you can clearly make out the giant C—a big, curving line in the sand. It will probably be around for a while.

Contributing editor Abe Streep () wrote about shark catcher Chris Fischer in February.