The Detective of Northern Oddities

When a creature mysteriously turns up dead in Alaska—be it a sea otter, polar bear, or humpback whale—veterinary pathologist Kathy Burek gets the call. Her necropsies reveal cause of death and causes for concern as climate change frees up new pathogens and other dangers in a vast, thawing north.

New perk: Easily find new routes and hidden gems, upcoming running events, and more near you. Your weekly Local Running Newsletter has everything you need to lace up! .

When they captured her off Cohen Island in the summer of 2007, she weighed 58 pounds and was the size of a collie. The growth rings in a tooth they pulled revealed her age—eight years, a mature female sea otter.

They anesthetized her and placed tags on her flippers. They assigned her a number: LCI013, or 13 for short. They installed a transmitter in her belly and gave her a VHF radio frequency: 165.155 megahertz. Then they released her. The otter was now, in effect, her own small-wattage Alaskan radio station. If you had the right kind of antenna and a receiver, you could launch a skiff into Kachemak Bay, lift the antenna, and hunt the air for the music of her existence: an occasional ping in high C that was both solitary and reassuring amid the static of the wide world.

Otter 13, they soon learned, preferred the sheltered waters on the south side of Kachemak Bay. In Kasitsna Bay and Jakolof Bay, she whelped pups and clutched clams in her strong paws. She chewed off her tags. Some days, if you stood on the sand in Homer, you could glimpse her just beyond Bishop’s Beach, her head as slick as a greaser’s ducktail, wrapped in the bull kelp with other females and their pups.

“They’re so cute, aren’t they?” said the woman in the gold-rimmed eyeglasses. She was leaning over 13 as she said this, measuring a right forepaw with a small ruler. The otter’s paw was raised to her head as if in greeting, or perhaps surrender. “They’re one of the few animals that are cute even when they’re dead.”

Two weeks earlier, salmon set-netters had found the otter on the beach on the far side of Barbara Point. The dying creature was too weak to remove a stone lodged in her jaws. Local officials gathered her up, and a quick look inside revealed the transmitter: 13 was a wild animal with a history. This made her rare. She was placed on a fast ferry and then put in cold storage to await the attention of veterinary pathologist Kathy Burek, who now paused over her with a sympathetic voice and a scalpel of the size usually seen in human morgues.

The far north isn’t just warming. It has a fever. This matters to you and me even if we live thousands of miles away, because what happens in the north won’t stay there.

Burek worked with short, sure draws of the knife. The otter opened. “Wow, that’s pretty interesting,” Burek said. “Very marked edema over the right tarsus. But I don’t see any fractures.” The room filled with the smell of low tide on a hot day, of past-expiration sirloin. A visiting observer wobbled in his rubber clamming boots. “The only shame is if you pass out where we can’t find you,” Burek said without looking up. She continued her exploration. “This animal has such dense fur. You can really miss something.” She made several confident strokes until the pelt came away in her hands, as if she were a host gently helping a dinner guest out of her coat. The only fur left on 13 was a small pair of mittens and the cap on her head, resembling a Russian trooper’s flap-eared ushanka.

It had been nearly a year since Burek’s inbox pinged with notice of a different dead sea otter. Then her e-mail sounded again, and again after that. In 2015, 304 otters would be found dead or dying, mostly around Homer and Kachemak Bay, on Alaska’s Kenai Peninsula. The number was nearly five times higher than in recent years. On one day alone, four otters arrived for necropsy. Burek had to drag an extra table into her lab so that she and a colleague could keep pace—slicing open furry dead animals, two at a time, for hours on end.

As they worked, an enormous patch of unusually warm water sat stubbornly in the eastern North Pacific. The patch was so persistent that scientists christened it the Blob. Researchers caught sunfish off Icy Point. An unprecedented toxic algal bloom, fueled by the Blob, reached from Southern California to Alaska. Whales had begun to die in worrisome numbers off the coast of Alaska and British Columbia—45 whales that year in the western Gulf of Alaska alone, mostly humpbacks and fins. Federal officials had labeled this, with an abstruseness that would please Don DeLillo, an Unusual Mortality Event. By winter, dead murres lay thick on beaches. The Blob would eventually dissipate, but scientists feared that the warming and its effects were a glimpse into the future under climate change.

What, if anything, did all this have to do with the death of 13? Burek wasn’t sure yet. When sea otters first began perishing in large numbers around Homer several years ago, she identified a culprit: a strain of streptococcus bacteria that was also an emerging pathogen affecting humans. But lately things hadn’t been quite so simple. While the infection again killed otters during the Blob’s appearance, Burek found other problems as well. Many of the otters that died of strep also had low levels of toxins from the Blob’s massive algal bloom, a clue that the animals possibly had even more of the quick-moving poison in their systems before researchers got to them. They must be somehow interacting. Perhaps several problems now were gang-tackling the animals, each landing its own enervating blow.

Burek’s lilac surgical gloves grew red. She noted that the otter had a lung that looked “weird.” She measured a raspberry-size clot on a heart valve using a piece of dental floss. She started working in the abdomen.��

“Huh,” she said. She’d noticed that the lower part of the otter was filled with brown matter and bits of shell: the nearly digested remains of the animal’s last meals had spilled into its pelvis and down into a leg wound. This could have caused an infection and also led to blood poisoning. But where was the injury?

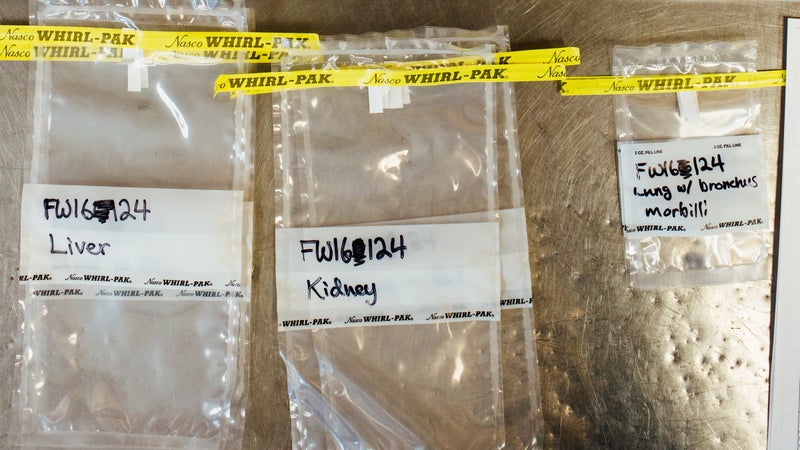

“The colon got perforated. I have no idea how,” Burek said. She probed further until she found a pocket of something like pus at the top of the femur. She eventually separated the femur from the body, and her assistant placed the bone in a Ziploc bag.

By now it was past lunchtime. Burek had been at the necropsy table for more than three hours without pause. She looked a little weary. What caused the otter’s death would remain, for the moment, unresolved. The not knowing seemed to displease her, though Burek was accustomed to mystery. The frozen north was always shifting; you took it as you found it.

Burek straightened stiffly. “I’m hungry,” she said across the bloody table. She removed the otter’s head and reached for the bone saw. “Who likes Indian?”

Burek often spends her days cutting up the wildest, largest, smallest, most charismatic, and most ferocious creatures in Alaska, looking for what killed them. She’s been on the job for more than 20 years, self-employed and working with just about every organization that oversees wildlife in Alaska. Until recently, she was the only board-certified anatomic pathologist in a state that’s more than twice the size of Texas. (There’s now one other, at the University of Alaska.) She’s still the only one who regularly heads into the field with her flensing knives and vials, harvesting samples that she’ll later squint at under a microscope.��

Nowhere in North America is this work more important than in the wilds of Alaska. The year 2015 was the planet’s hottest on record; 2016 is expected to have been hotter still. As human-generated greenhouse gases continue to trap heat in the world’s oceans, air, and ice at the rate of four Hiroshima bomb explosions every second, and carbon dioxide reaches its greatest atmospheric concentration in 800,000 years, the highest latitudes are warming twice as fast as the rest of the globe. Alaska was so warm last winter that organizers of the Iditarod had to haul in snow from Fairbanks, 360 miles to the north, for the traditional start in Anchorage. The waters of the high Arctic may be nearly free of summertime ice in little more than two decades, something human eyes have never seen.

If Americans think about the defrosting northern icebox, they picture dog-paddling polar bears. This obscures much bigger changes at work. A great unraveling is underway as nature gropes for a new equilibrium. Some species are finding that their traditional homes are disappearing, even while the north becomes more hospitable to new arrivals. On both sides of the Brooks Range—the spine of peaks that runs 600 miles east to west across northern Alaska—the land is greening but also browning as tundra becomes shrubland and trees die off. With these shifts in climate and vegetation, birds, rodents, and other animals are on the march. Parasites and pathogens are hitching rides with these newcomers.

“The old saying was that our cold kept away the riffraff,” one scientist told me. “That’s not so true anymore.”

During this epic reshuffle, strange events are the new normal. In Alaska’s Arctic in summertime, tens of thousands of walruses haul out on shore, their usual ice floes gone. North of Canada, where the fabled Northwest Passage now melts out every year, satellite-tagged bowhead whales from the Atlantic and Pacific recently met for the first time since the start of the Holocene.��

“We’ve probably cut up more sea otters than anyone else on the planet,” Burek told me. “Congratulations,” I said. “We all got to brag about something,” she replied.

These changes are openings for contagion. “Anytime you get an introduction of a new species to a new area, we always think of disease,” Burek told me. “Is there going to be new disease that comes because there’s new species there?”

A lot of research worldwide has focused on how climate change will increase disease transmission in tropical and even temperate climates, as with dengue fever in the American South. Far less attention has been paid to what will happen—indeed, is already happening—in the world’s highest latitudes, and to the people who live there.��

Put another way: The north isn’t just warming. It has a fever.��

This matters to you and me even if we live thousands of miles away, because what happens in the north won’t stay there. Birds migrate. Disease spreads. The changes in Alaska are harbingers for what humans and animals may see elsewhere. It’s the front line in climate change’s transformation of the planet.

This is where Burek comes in. Fundamentally, a veterinary pathologist is a detective. Burek’s city streets are the tissues of wild animals, her crime scenes the discolored and distended organs of tide-washed seals and emaciated wood bison. “She’s the one who’s going to see changes,” says Kathi Lefebvre, a lead research biologist at Seattle’s , a division of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). “She’s the one who’s going to see epidemics come along. And she’s the one with the skills to diagnose things.”

As the planet enters new waters, Burek’s work has made her one of the lonely few at the bow, calling out the oddness she sees in the hope that we can dodge some of the melting icebergs in our path. It’s a career that long ago ceased to strike Burek as unusual, and she moves without flinching through a world tinged with blood and irony. The first time we spoke on the phone, Burek offhandedly said of herself and a colleague, “We’ve probably cut up more sea otters than anybody else on the planet.”

“Congratulations,” I said.

“We all got to brag about something,” she replied.

Summer is the season when Alaskans at play under the undying sun tend to come across dead or stranded animals and place a call to a wildlife hotline. The call starts a chain of events that often ends at Burek’s family home, which is made of honey-colored logs and sits on an acre and a half in Eagle River, about 20 miles north of downtown Anchorage. This is where the asphalt yields to Alaska. The rough peaks of the Chugach Mountains, still piebald with snow in midsummer, lean overhead. Moose occasionally carry off the backyard badminton net in their antlers.

In July, I headed north from Seattle to spend a month with Burek as she worked. She’s 54 but looks a decade younger, with long brown hair and appled cheeks that give her the appearance of having just come in from the icicled outdoors. Her voice has an approachable Great Plains flatness, the vestige of her Wisconsin birth and an upbringing in the suburbs of Ohio. Burek ends many sentences with a short, sharp laugh—a punctuative caboose that can signal either amusement or bemusement, depending. Growing up in the Midwest, she didn’t see the ocean until high school. “But I was always fascinated by whales,” she told me. “And I always wanted to be a vet or a wildlife biologist—Jane Goodall or something.” She laughed. “Lots of kids wanted to be vets. They outgrow it.”

Burek was intrigued by the biology—how bodies worked and how, sometimes, they didn’t. After college she went to veterinary school at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, later moving to Alaska to see how she would like working in a typical vet practice. One year she lived outside Soldotna, in a one-room “dry” cabin, with no running water, while writing her thesis for a master’s degree in wildlife disease virology. Alaska agreed with her. “I like the seasons. I like the wilderness. I like the animals,” she said.

Burek met her future husband, Henry Huntington, on the coast of the Chukchi Sea in the high Arctic, during the Inupiat’s annual spring bowhead whale hunt, when breezes pushed the ice pack together and forced a pause in the whaling. They now have two teenage sons. “I tell the boys they’re the product of persistent west winds in May of 1992,” said Henry, a respected researcher and scientist with the .��

Surprisingly little is known about the diseases of wildlife. As a result, many veterinary pathologists end up focusing on a few species. Thanks to Burek’s curiosity and her gifts, and to a necessary embrace of the Alaskan virtue of do-it-yourself, her expertise is broad. “Anyone who gets into this kind of thing, you like a puzzle,” she told me. “You have to pull together all kinds of little pieces of information to try to figure it out, and it’s very, very challenging.”

Over the years, Burek has peered inside just about every mammal that shows up in Alaskan field guides. One morning, as we drank coffee at her kitchen table, she rattled off a few dozen examples. Coyotes. Polar bears. Dall sheep. Five species of seals. As many whales, including rare Stejneger’s beaked whales.��

As we talked, I wandered into the living room. On a wall not far from the wedding photos hung feathery baleen from the mouths of bowhead whales and the white scimitars of walrus tusks. Upstairs in a loft lay an oosik—the baculum, or penis bone, of another walrus. It was as long as a basketball player’s tibia. Atop the fireplace mantel, where other families might display pictures of wattled grandparents, grinned a row of skulls: brown bear, lynx, wood bison. Burek tapped one of the skulls in a spot that looked honeycombed. “Abscessed tooth,” she said. “Wolf. One of my cases.”

Working on wild animals, often in situ, routinely presents her with job hazards that simply aren’t found in the lower 48. Anchorage sits at the confluence of two long inlets. When Burek performs necropsies on whales on Turnagain Arm, she has to keep a sentry’s eye on the horizon for its infamous bore tide, when tidal flow comes in as a standing wave, fast enough that it has outrun a galloping moose. Knik Arm is underlain in places by a fine glacial silt that, when wet, liquefies into a lethal quicksand. Burek’s rule of thumb in the field is never to sink below her ankles. Not long ago, while taking samples from a deceased beluga, she kept slipping deeper. Exasperated, she finally climbed inside the whale and resumed cutting.

Then there’s the problem of the whales themselves. “Whales are just like Crock-Pots,” Burek said. “They’re kind of encased in this thick layer of blubber that’s designed to keep them warm. They might look OK on the outside, but inside everything is mush.”

Decay is the nemesis of the pathologist. Decay erodes evidence. “Fresher is always better,” Burek said, sounding like a discerning sushi chef. It isn’t possible every time. Colleagues told me about a trip with Burek to a remote beach outside Yakutat, to do a postmortem on a humpback. There were several in the group, including a government man with a shotgun to keep away the brown bears that sometimes try to dine on Burek’s specimens. It was raining and cold, and the whale had been dead for a while. Inside, the organs were soup. The pilot who retrieved them had to wear a respirator.��

“My wife,” Henry told me, “has a high threshold for discomfort.”

One morning in Anchorage, my phone buzzed. To get a text from Burek is to gain new appreciation for the cliché mixed emotions. Often it’s a chirpy message notifying you that another of God’s creatures has expired and would you like to come see the carcass?

Burek picked me up at a coffee shop on Northern Lights Avenue, driving the family’s Dodge Grand Caravan with a cracked windshield. �����ԹϺ��� it was sunny and warm; just two days earlier, it hit 85 in Deadhorse, the highest temperature ever recorded on the North Slope. Burek’s eyeglasses were covered by sun blockers of the type sold on late-night television. She was wearing summer sandals, her toenails painted what a saleswoman would call “aubergine.” Her foot pressed the gas. We were going to pick up a dead baby moose.

“Fish and Game wants to know why it died, if it’s a possible management issue,” Burek said. Last year an adenovirus, which is more commonly seen in deer in California, had killed two moose in Alaska. Officials wanted to know how common adenovirus was in the state.

As work went, it was an unremarkable day for Burek. The past several years had presented her with a string of cases that were altogether more intriguing and odder and more frustrating for their open-endedness. In 2012, Burek and others observed polar bears that had suffered a curious alopecia, or hair loss, but they were unable to pinpoint the reason. In 2014, Burek described a sea otter that had died of histoplasmosis, an infection caused by a fungus that’s usually found in the droppings of midwestern bats. The infection will sometimes afflict spelunkers, which is where it gets its common name: cave disease. The finding was a dubious first, both for a marine mammal and for Alaska. But, again, why? What was a midwestern fungus doing inside an otter plashing off the coast of Alaska?

Then there was the strange case of the ringed seals. In the spring of 2011, native hunters in Barrow, the northernmost town in the U.S., started finding ringed seals that didn’t look right. The animals had lesions around their mouths and eyes, and ulcers along their flippers. Some had gone bald. A handful died.��

Soon, down the coast at the major walrus rookery at Point Lay, ulcers started turning up on walruses both living and dead. The number of sightings on spotted and bearded seals increased and spread south into the Bering Strait as the summer progressed. In time, a few ribbon seals were also affected. Federal officials labeled it another Unusual Mortality Event, a signal of concern and a call for more study. Burek led the postmortems, opening up dozens of animals. Researchers sent samples as far away as Columbia University, in New York, for molecular work. They tested many ideas, but the cause eluded them.

Was climate change a factor in the events? The evidence intrigued Burek and her colleagues. Seals molt during a brief span of time in the spring. According to Peter Boveng, the polar ecosystems program leader at NOAA’s , the longer days and warming temperatures likely cue the animals to climb onto the sea ice, so their skin can warm up and start the process of dropping old hairs and growing new ones. Having ice present is probably crucial for this molting process to happen, Boveng and others believe.

But what if a warming north meant less ice for the seals to use, interfering with their molt? That would explain why the animals showed lesions in the same places on their bodies where the molt begins—the face, the rear end. And when the skin is unprotected by fur, Burek told me, “it may be susceptible to secondary inflections” from bacteria and fungi in the environment.

Nature, alas, is messy and confusing. Though the reasoning seemed plausible, there was no widespread lack of spring ice in 2011 in the areas where the diseased seals were found. Deepening the mystery, lesions in walruses all but vanished in subsequent years, even as some seals continue to have them. “It’s very frustrating—very frustrating,” Burek said of trying to tease out an answer. A lot of her work remains unresolved. Burek knows that this is the reality of doing her job in the 49th state. It is a vast place, expensive to do research; scientists often haven’t been able to do enough baseline studies to know what’s normal and expected, versus new and worrisome, in a given population. Still, it chews at her, the inability to give answers to concerned native peoples. “I have enough self-doubt that it’s like, well, maybe it’s because I’m not working hard enough, or I haven’t done the right thing to figure it out.”

To be sure, the far north isn’t collapsing under contagion caused by climate change. And Burek is careful about drawing connections. Still, a good detective doesn’t need a smoking gun to know when a crime has been committed. Circumstantial evidence, if there’s enough of it, and the right kinds, can tell the story. “It seems hard to believe,” Burek told me, “that a lot of these changes aren’t related to what’s going on in the environment. The problem is proving it.”

There’s a larger question, too, about what these developments augur for humans. The answer, researchers are finding, is that it’s already starting to matter.

Time was, the cold and remoteness of the far north kept its freezer door closed to a lot of contagion. Now the north is neither so cold nor so remote. About four million people live in the circumpolar north, sometimes in sizable cities (Murmansk and Norilsk, Russia; Tromso, Norway). Oil rigs drill. Tourist ships cruise the Northwest Passage. And as new animals and pathogens arrive and thrive in the warmer, more crowded north, some human sickness is on the rise, too. Sweden saw a record number of tick-borne encephalitis cases in 2011, and again in 2012, as roe deer expanded their range northward with ticks in tow. Researchers think the virus the ticks carry may increase its concentrations in warmer weather. The bacterium Francisella tularensis, which at its worst is so lethal that both the U.S. and the USSR weaponized it during the Cold War, is also on the increase in Sweden. Spread by mosquitoes there, the milder form can cause months of flu-like symptoms. Last summer in Russia’s far north, anthrax reportedly killed a grandmother and a boy after melting permafrost released spores from epidemic-killed deer that had been buried for decades in the once frozen ground.

Alaska hasn’t been immune to such changes. A few months ago, researchers reported that five species of nonnative ticks, probably aided by climate change, may now be established in the state. One is the American dog tick, which can transmit the bacterium that causes Rocky Mountain spotted fever, which can lead to paralysis in both canines and humans. In 2004, a bad case of food poisoning sent dozens of cruise-ship passengers running to their cabins. The culprit was Vibrio parahaemolyticus, a leading source of seafood-related food poisoning.��

Turned out of the tote onto the steel table, the moose calf was the size of a full-grown Labrador. It lay with its legs folded, as if it was just bedding down in soft lettuce.

V. parahaemolyticus is typically tied to eating raw oysters taken from the warm waters of places like Louisiana. Why was it infecting people 600 miles north of the most northerly recorded incident? Health officials later teased out the reason: summer water temperatures in Prince William Sound, where the oysters are farmed, now gets warm enough to activate the bacterium.

Earlier in 2016, Burek and NOAA’s Lefebvre coauthored a paper about their discovery of domoic acid in all 13 species of Alaskan marine mammals they examined, from Steller sea lions to humpback whales, in waters as far north as the Arctic Ocean. Domoic acid is naturally produced by some species of algae, and it moves through the food web as it accumulates in the filter-feeding animals that dine on it—anchovies, sardines, crabs, clams, and oysters. Scientists knew the algae that makes domoic acid were present, but they never had a report of a bloom that far north before 2015. The hunch is that warming waters may be increasing the toxin’s presence in Alaska.

“What’s going to happen to these 100-year-old whales when they get hit by these neurotoxins three years in a row?” Lefebvre said. “And it’s not just mortality. It’s sub-lethal neurological effects.”

A study published in 2015 in the journal Science found that harmful algal blooms off the California coast have caused enough brain damage to California sea lions that they lose their way and have trouble hunting. “This is a shot across the bow,” Lefebvre said of the algal blooms. “It’s the type of thing that could happen and become more common.”

Here’s the broader lesson: if the animals can get sick, we can get sick, whether it’s from invigorated pathogens in the environment or from ailing animals themselves. Three in four emerging infectious diseases in humans today are zoonotic diseases—illnesses passed from animals to humans.

This is one reason Burek has a soft spot for sea otters like 13: they are excellent sentinels for what’s happening in the world. Otters splash in the same waters where humans live, work, and play. They eat the same seafood humans do. “I call them a pathologist’s wonderland, because they get all the fantastic, extreme infectious diseases—not to sound too unpleasant,” Burek said.

There are other reasons to pay attention to animals like otters. Mike Brubaker, director of community environment and health at the Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium, points out that traditional foods—everything from salmonberries to moose meat—still make up 80 percent of the native diet in some remote Alaskan communities. If animals suffer, then traditional diets suffer, and so do the cultures that revolve around hunting, fishing, and foraging.

Making Burek's job even more complicated, animals frequently die from mysterious causes that may have nothing at all to do with climate change. As she pokes through the bones, her constant challenge is to discern what’s notably weird from what’s simply everyday and unfortunate.

Near the airport, Burek turned into Alaska Air Cargo, backed up to a loading dock, and parked the van. “It’s surprising how often they can’t find the carcass,” she said. We went inside. Burek handed a tracking number to an agent behind the counter. A man driving a forklift soon appeared at the loading dock. The forklift was freighted with a 31-gallon blue Rubbermaid Roughneck Tote labeled unknown shipper. Burek opened the hatchback of the minivan and pushed aside pairs of Xtratuf rubber boots. The tote weighed a lot, but not so much that one man couldn’t lift it.

We drove east through the sunny noonday traffic of Anchorage with a dead baby moose in the rear of the minivan. Burek was in a good mood, as she usually was. Years of working in close proximity to death had resulted in a sort of over-the-fence neighborliness with the macabre. She told me how area hospitals occasionally helped her determine cause of death by performing CT scans of dead baby orcas or by putting the heads of juvenile beaked whales into their MRI machines to look for acoustic injuries from Navy sonar or energy exploration. “I’m surprised this car doesn’t smell worse for all the things that have been in it,” she said. “I had a bison calf delivered to me, and it was in a tote like that, but it didn’t fit—so these four legs were sticking out.”

We arrived at a lab at the University of Alaska Anchorage, where Burek is an adjunct professor. The room was small, with white walls, a steel table at the center, and a drain in the floor. Burek pulled on a pair of rubber Grundens crabbing bibs the color of traffic cones, stepped into the tall boots from the minivan, and pulled her hair back. She could have been headed for a day of dip-netting for sockeye on the Kenai. An assistant laid out tools.��

A big pair of garden shears sat on the counter, as foreboding as Chekhov’s gun on the mantle.

“You’re probably gonna want to put on gloves for this,” she said.��

Turned out of the tote onto the steel table, the moose calf was the size of a full-grown Labrador. It lay with its legs folded, as if it was just bedding down in soft lettuce. Burek flipped the calf onto its left side, which was how she liked to work on her ruminants. Then she began, calling out information. Sex: female. Weight: 74 pounds. Death: July 13. Length: 116 centimeters. Axillary girth: 76 centimeters. She swabbed an obvious abscess, open and draining, on the right shoulder. She noted the pale mucus membranes. She inserted a syringe into an eyeball to sample the aqueous humor. She returned to the shoulder, to the painful-looking abscess, and removed a piece of it for later examination on a glass slide under a microscope. Then Burek pressed her fingers into the wound.��

“Oh, that’s kind of gross,” she said. “There’s a comminuted fracture in there.” When not using a scalpel and forceps, Burek often uses her fingers. After years of practice, her touch serves almost as a caliper and gauge. She will bread-loaf a liver and pinch the sections, probing for hardness. She will run her fingers along a wet trachea in search of abnormalities. “Oh, feel that,” she will say to anyone willing to feel that.��

Burek cut deeper to expose the wound. “Oh. Oh. Poor thing. It probably got nailed,” she said. The detective was hitting her stride now. Searching the exterior of the calf, Burek quickly found what she was looking for a second puncture wound, this one also badly infected. She measured the distance between the wounds: 5.5 centimeters, or the approximate distance, she estimated, between a bear’s canines. “So that’s cool.”

In an interesting coincidence, Burek later would tell me she suspected that, for all the other abnormalities she found inside 13—the clot, the weird-looking lung—perhaps the otter, too, was ultimately done in by something as mundane as a predator. Blunt-toothed young killer whales will sometimes grab otters but not kill them, she explained; they sort of play with their food. Burek had seen it before. Intrigued, she telephoned the in Fairbanks and asked colleagues to measure the skull of a juvenile orca for an estimate of the diameter of its bite. The measurement perfectly fit the damage. “Of course, we’ll never know for sure,” she said. Still, there was a trace of satisfaction in her voice.

Now, using a No. 20 scalpel, Burek quickly skinned the moose calf and opened the stubborn clamshell of the rib cage. An unwelcome visitor wafted into the room. Burek, however, no longer seemed to notice odors that, were they canistered and lobbed across international borders, would swiftly be outlawed by the Geneva Conventions. As she worked, the gore took on a practiced orchestration. Burek cut triangles of beet-colored liver and dropped them into prelabeled bags with a pair of medical tweezers. She took samples of lung and lymph node and gall bladder. She squeezed the descending colon and collected the pellets. She filled vials and syringes. Some of the bits she did not even bother to label; after decades, Burek could recognize them by sight. With a few slices, she opened the firm dark knot of the heart like a chapbook and removed what resembled red chicken fat. At home Burek would spin the stuff in a centrifuge. Stripped of its red blood cells, the clear blood serum was an excellent way to see which infectious agents the animal had been exposed to in the past. “Diagnostic gold,” Burek called it.

The table took on the appearance of a Francis Bacon canvas: A smear of blood. An ear divorced from a head. The sprung cage of the moose’s body exposing its soft, translucent clockworks. The open mouth mutely horrified. Burek noted a hemorrhage on the surface of the pancreas and fibrin on the peritoneal cavity, and she moved on. The door of the lab stood open to the smiling July afternoon. Sunlight caught on aspen leaves. One of the two young women who were assisting Burek had just returned from her first year of veterinary school. Burek was her inspiration, she said. As the women laughed and worked, Burek quizzed her on biology and she told stories.

“I had a horse head in my freezer one time.”

“Bears smell absolutely horrible. I did a bear necropsy in our garage once, and my son Thomas said I could never do that again.”

“Can I get some muscle?”

“Those large whales? Holy cow. It’s so confusing: Where the heck is the urinary bladder?”

“For a while, I had a big colony in my garage of those flesh-eating beetles that museums use to clean skulls. But a couple of the beetles got out. That’s when Henry put his foot down.”

“Where’d my duodenum tag go? Anyone seen it?”

“I don’t think rumens smell that bad. But I went to vet school in Wisconsin.”

The steel table slowly emptied. The blue Rubbermaid bin filled. In went a foreleg.��

Intestines. The ear.

Now another assistant lifted the garden shears. She squeezed and sliced through the ball joint of the calf’s femur, which is one of the best places on a young animal for Burek to see evidence of troubles, such as rickets, that would affect its growth plates. Burek, meanwhile, opened the skull to sample the brain.

“It’s a bit of a mystery,” she said as she worked, meaning the cause of the moose’s death. Her initial guess: the bite led to septicemia, which led to encephalitis. “It’s a story that kind of makes sense,” she said. “I’d like to see more pus.” Later she added: “But in this job you have to be willing to look dumb and be wrong and change your story.”

Burek asked for the time. When I told her it was after four o’clock already, her good humor slipped. “I’ve got to get to the dump.” What was the hurry?

There was a new movie she wanted to see at seven, she said. She would have to race home to shower—to wash off the day, to wash off the smell, the blood, the moose.

“It’s a Disney movie, I think,” Burek said.��

A film about animals run amok. “It’s called The Secret Life of Pets.” She loaded the moose in the back of the minivan and reached for the bleach. “It looks cute.”

Contributing editor Christopher Solomon () wrote about the Utah Wilderness wars in March 2016. This story was supported by a grant from the .