Morning comes bright and dry to the Mayacamas Mountains on the eastern edge of Sonoma County, near the heart of Northern California wine country. Bernie Krause, a 77-year-old pioneer in the field of soundscape ecology, has been up for hours, sitting at his favorite spot in Sugarloaf Ridge State Park, his ears tuned to the awakening day. What he’s hearing is absence, the quiet of loss.

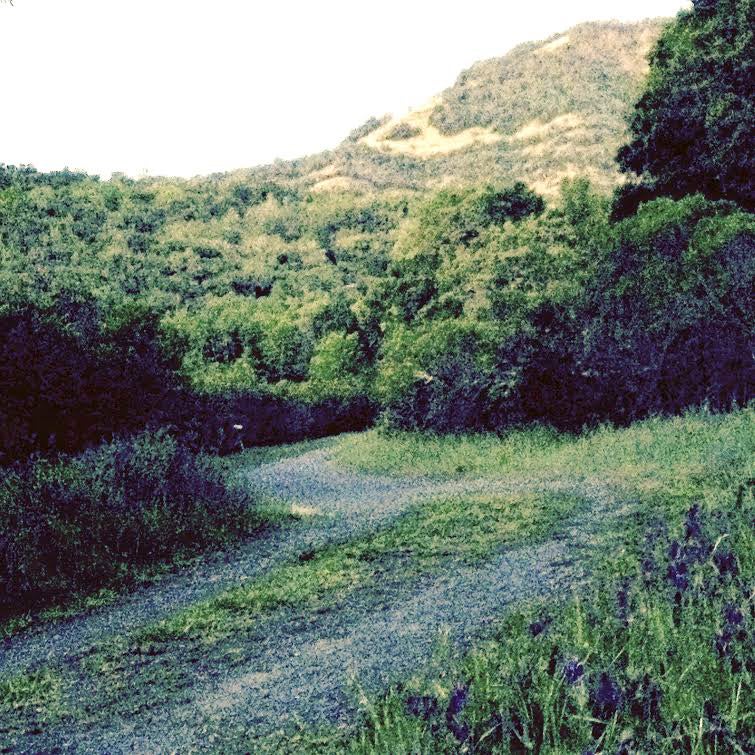

Krause is nestled in a valley, surrounded by scrub vegetation, oak trees, and alders. One hundred paces to his right, a tripod mounted with microphones stands in a shrinking patch of shade cast by thirsty oaks and alders. Fifty paces to his left, the five-foot-wide bed of Sonoma Creek twists through brush, its stones coated with a fine layer of dust. Krause remembers the quick, rambunctious flow of wetter years, the silvery song of ripples and cascades. For the past few years, however, warmer days arrive earlier in the year, and vegetation cycles begin and end sooner. “When the stream has no water because of the lack of precipitation, the stillness is eerie,” he says.

To the eye, the Sugarloaf site looks pretty much the same as ever, save for the parched creek hidden away in the shrubs. That’s why the soundscape is so important. In Krause’s words: “It tells the story more eloquently, from a different perspective.”

Since 1994, Krause has visited this site each spring to record the dawn chorus of birds, always using the same gear and techniques, and always at the same times of day. His career of listening has led him on dozens of expeditions to remote, wild locales—Borneo, the Arctic, the Dzanga-Sangha rainforest in Africa—but throughout these travels Sugarloaf Ridge State Park has served as a kind of acoustic anchor. It’s his home terrain, only 20 minutes by car from his house, a convenient place to slip away and lose himself in the layering of chirps and burbles. With the failing rains, though, the music he’s come to cherish has mostly disappeared.

Between 2004 and 2015, the site’s biophony (totality of sounds produced by living organisms) dropped in level by a factor of five. “It’s a true narrative, a story telling us that something is desperately wrong,” Krause says.

Sadly, disappearance is nothing new. , built over four decades, consists of more than 5,000 hours of what he calls “whole-habitat” field recordings from around the world. More than half of the habitats represented—from desert buttes to tidal pools to alpine meadows—are either totally silent or have been reduced over the course of his recording sessions due to impacts from logging, mining, real estate development, poaching, airplane traffic, warfare, and climate change. And, of course, climate change’s little sibling: drought.

“Because the changes take place from year to year, over a long stretch of time, I really wasn’t aware of what was happening,” Krause says of his Sugarloaf site. “It was only when I set up the examples side by side that the changes became apparent. The impact of the drought was both astonishing and alarming.”

With his colleague Almo Farina, a professor at Italy's University of Urbino, Krause is currently working on an academic paper that will turn his Sugarloaf recordings into crunchable numbers. Already, some preliminary results are emerging. The avian density (total numbers of individual birds) and avian diversity (total number of species) has declined dramatically since the early 2000s. Where there had been Brewer’s sparrows, acorn and pileated woodpeckers, black-headed grosbeaks, red-shouldered hawks, wild turkeys, and a handful of other species, now only a few California towhees, dark-eyed juncos, and white-breasted nuthatches can be heard. (Why those species have weathered the drought when others haven’t isn’t exactly clear—Krause’s paper could answer that question.) Between 2004 and 2015, the site’s biophony (totality of sounds produced by living organisms) dropped in level by a factor of five. “It’s a true narrative, a story telling us that something is desperately wrong,” Krause says.

The California drought gets a lot of press these days, as does ecological collapse in general, and the grim news can sometimes have a numbing effect on people who might otherwise be genuinely concerned. Perhaps that’s the special value of Krause’s work—not what it tells us of the changing ecosystem, but how it tells us, how it speaks directly to our feelings, the part of each human that can be moved by a Mozart concerto or a Led Zeppelin riff, the part that exists before and beneath the intellect, that can be filled to the brim.

Krause frequently refers to our planet’s diverse, evolved biophonies as “the voice of the divine.” The spring of 2015, by comparison, was muted, hollow, sad, and Sugarloaf Ridge a weak mimic of its lusher self, he says. “Whether or not the habitat will regain its biophonic vitality with the expected coming precipitation this winter remains to be seen,” he says.

After an hour of dawn recording, the sun begins its daily climb and Krause packs up his gear. In the space where there was once a chorus of intricate textures and complex rhythms, now there is a question: What will next spring sound like? He heads down the trail. For the time being, the recording session is over.