The pictures were at least 5,000 years old, maybe as old as 8,500. For millennia, since an unknown Native artist engraved them into a volcanic boulder, the collection of abstract geometric shapes had sat in this rocky valley on the outskirts of whatтАЩs now , the homelands of the Coahuiltecan, and , Jumanos, and Chisos people. In that time, they had endured rain, wind, and punishing desert sun.

What finally did them in was a tourist who wanted to leave a mark.

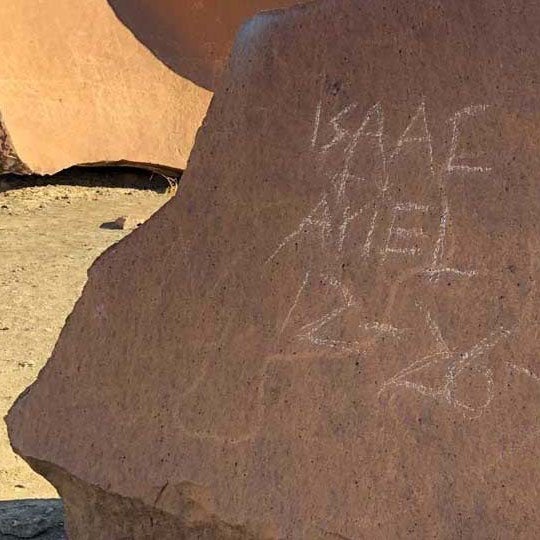

On December 26, the in the parkтАЩs Indian Head area, leaving bright white scratches crisscrossing the ancient rock art. While Park Service personnel moved quickly to repair the vandalism, as Tom VandenBerg, Big BendтАЩs chief of interpretation and visitor services, noted in a phone call, much of the damage is permanent. It was the latest example of visitors damaging ancient rock artтАФa scene thatтАЩs becoming all too common on public lands.

Last monthтАЩs incident is at least the 50th time someone has vandalized a petroglyph in Big Bend National Park since 2015, and itтАЩs the latest in a string of high-profile defacements that have occurred on public lands throughout the United States. Last April, land managers near Moab announced that , an intricate piece of rock art that is popular with hikers. A month earlier, archaeologist Johannes Loubser discovered that someone had spray-painted and etched over a set of 3,000-year-old carvings at Track Rock Gap in northern Georgia, a culturally important and sacred site to the Creek and Cherokee people. The graffiti takes just a few minutes to do with a knife or a can of spray enamel. Removing it can take weeksтАФand some of the scars are irreversible.

тАЬOnce something is done, youтАЩre never going to undo it completely. There are always going to be traces,тАЭ Loubser says. тАЬEven restoration cannot bring something back. When you get out of [heart] surgery, is your heart as good as before?тАЭ

Loubser, who holds a PhD in archaeology, specializes in rock art. Over the past four decades, heтАЩs worked on four continents, cataloging cave paintings in South Africa and working to conserve and manage culturally significant sites in Australia. As the founder of the archaeological consulting firm , Loubser contracts with federal and state government and private groups to preserve and repair Native rock art across the United States, surveying petroglyphs and remedying the modern-day damage done to them by tourists who are determined to leave a mark. In his own words, LoubserтАЩs job is to create тАЬchaos out of order and order out of chaos.тАЭ By removing vandalsтАЩ scratches and spray paint, he restores the natural, chaotic surface of the rock. Paradoxically, doing so allows the order of the original artistsтАЩ work to shine through.

While it would be easy to assume that the Covid-driven increase in outdoor recreation has led to more vandalism, Loubser and VandenBerg say the actual effect of the boom isnтАЩt clear yet. Instead, rock art vandalism is better understood as a long-term trend, says Loubser, who has documented graffiti thatтАЩs more than a century old. Graffiti became commonplace in the 1910s, then declined in the 1960s (тАЬpeople were really well-behavedтАЭ). In the 1990s, it began to swell again, with graffiti representing тАЬa variety of nationalities and language groups,тАЭ Loubser says, and it hasnтАЩt abated since then. The content has occasionally changed over the years: on a recent job along the Columbia River in Washington, Loubser found himself removing political slogans from the rock.

When vandalism does occur, he says, . Not just for the beauty or significance of the marred art, but for the message it sends to future visitors.

тАЬI hate to say this, but that first person [to vandalize a piece of rock art] takes a bit of initiative,тАЭ he says. тАЬOnce thereтАЩs graffiti, the next people who come along, itтАЩs easier to do.тАЭ Keeping sites neat and clean sends a message to everyone who encounters it that тАЬthis place is important.тАЭ

How Loubser and his collaborators treat vandalized rock art depends on a variety of factors. First of all, thereтАЩs the original art theyтАЩre restoring. Boldly sculpted or painted pictographs and petroglyphs are easier to work around, while fine-lined carvings demand a bit more caution. Then thereтАЩs the nature of the vandalism. Simple drawings with charcoal or chalk may only need to be lightly brushed off; more stubborn, wet-applied charcoal may require a toothbrush or even a steel brush if itтАЩs older. They often abrade off spray paint and incised graffiti with a sandblaster, or theyтАЩll grind it off with a wire brush mounted on a drill, sometimes filling in the leftover marks with pigment thatтАЩs been laboratory-matched to the color of the stone. Which techniques they use are informed by consultation with land managers and local tribes, which often have a cultural or spiritual stake in the site.

Sometimes, well-meaning amateurs try to clean up the graffiti themselves. The results often make matters even worse, as happened in Big Bend. When Lin Pruitt, a National Park Service archaeological technician, and Thomas Alex, a retired archaeologist for the agency, visited the site two days after the vandalism was first reported, they found that a visitor had attempted to тАЬtreatтАЭ the graffiti with the water from their bottle. The chlorine in the tap water had reacted with the stoneтАЩs natural patina to form a white stain, further discoloring the panel.

The two set to work, removing the remains of the graffiti and the white stain by spraying it down with distilled water and daubing it off. On a second visit a few days later, the duo used a soft-bristled brush to further loosen the stain. When they were done, the petroglyphs were almost back to their original stateтАФalmost. A close look would reveal faint scratches and the remnants of the new stain.

ThatтАЩs the trouble with removing graffiti from rock art after the fact: no matter how careful or skilled the personnel, traces always remain. This is why preventing vandalism in the first place is so crucial, Loubser says. In some well-trafficked, well-funded areas, land managers might put motion-detecting cameras in place to catch vandals in the act and hold them legally accountable or appoint volunteer stewards to deter people who mean to mar the art. In most places, however, the best and only feasible solution is to make sure visitors understand the importance of what theyтАЩre looking at.

тАЬThere is no direct relationship between the amount of people who visit a place and the graffiti damage,тАЭ Loubser says. тАЬI would say itтАЩs more the kind of people and the management context. If people are backpackers and theyтАЩre informed, theyтАЩre not going to do it. There could be thousands of them, and theyтАЩll leave the site clean. But ill-informed people and people who are not educated, who donтАЩt realize what rock petroglyphs and pictographs are and that theyтАЩre special to Native Americans, they act inappropriately.тАЭ In his experience, Loubser says, when those same people learn the immense significance of these ancient carvings and drawings, they often begin to treat them with more respect.

VandenBerg, for his part, has his doubts that whoever defaced the petroglyphs in Big BendтАФrangers have appealed to the public for help identifying themтАФdid so out of ignorance. He points out that thereтАЩs abundant signage around the area informing visitors about the petroglyphs and the penalties for harming them. ThereтАЩs one thing, however, that he knows for sure: their actions cost Big Bend something тАЬpriceless.тАЭ