HE’S CLOSE. VERY CLOSE. RUMORS place him here just yesterday, playing with a sea kayaker along this beach. He hung around for 15 minutes or so, swimming in circles, splashing and making his usual singsong squeals and clicks. No, he didn’t put on his trademark Big Show. But then, in recent years that spectacle has come less and less often.

Dolphin 56 Migration

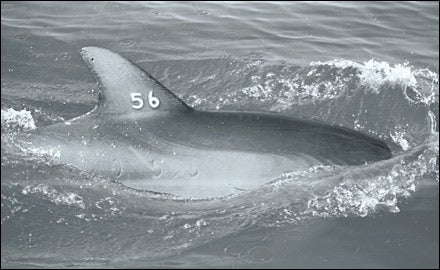

Still, he’s nearby. A forty-ish Atlantic bottlenose dolphin, with a number freeze-branded on both sides of his dorsal fin, giving him his now familiar moniker: Dolphin 56.

As usual, he’s spending late summer and fall hugging this stretch of southern New Jersey shore, a rugged line of dunes and sand known as Island Beach State Park, roughly a thousand miles from his Florida birthplace. I’m here, and hoping for a glimpse, aboard the 26-foot fishing boat Phyllis Ann, owned by captain Rod Houck. Two weeks ago to the day, Dolphin 56 swam up to the Phyllis Ann’s gunwale, lifted his head and upper body from the water, and let Houck and some fishing buddies rub his shoulders, snout, and forehead in amiable human-to-dolphin congress.

“It was one of the unforgettable moments of my life,” Houck says. He’s steering the Phyllis Ann out the narrow passage of Barnegat Inlet, past the last navigational pilings and into the broad Atlantic horizon just south of the park. It’s a warm late-summer Sunday. The ocean shimmers, flat and calm. Conditions are exactly like yesterday; exactly like two weeks ago, when the 44-year-old Houck first made contact with the dolphin who has become my obsession.

“It was the strangest thing,” Houck says. “We were motoring about a quarter-mile offshore, and I saw a single dolphin off our port side. So I shouted ‘Dolphin!’ to the guys and pointed at him, then backed off the engine. Soon as we slowed, he came toward the boat. Not porpoise-ing like normal dolphins, but with the top of his body a full third out of the water. He came toward us like a surfaced submarine. I thought, Now, that’s unusual. I didn’t know yet that he was so famous.”

1. NEW YORK

19982001: three sightings

2. DELAWARE & NEW JERSEY

Nearly 50 sightings between 1998 and 2008

3. MARYLAND & VIRGINIA

19972001: eight sightings

4. NORTH CAROLINA

199799: 69 sightings; two more in 2001 and 2004

5. SOUTH CAROLINA

199799: 11 sightings

6. GEORGIA

199798: two sightings

7. FLORIDA

Just over 40 sightings between 1979 and 1996

OVER THE PAST 15 years, and among a growing circle of followers that runs into the hundreds and includes everybody from marine scientists to curious water people, Dolphin 56 has built a legion of fans. In me and others, he’s inspired a condition I’ve come to call “Benign Ahab Syndrome,” or BAS. For the afflicted, our free moments tend to settle into the dream of shaking hands with Dolphin 56, Ambassador of the Atlantic. For years I’ve chased himor, more accurately, chased sightings of himfrom North Carolina’s Outer Banks to Delaware Bay, always without success.

At this point, actually seeing him has become almost a second-tier goalmaybe I will, maybe I won’t. But there’s always fun to be had in the quest, and since Dolphin 56 lives in the ocean, there are usually a few good seafood meals thrown in. So everybody wins.

But we should start closer to the beginning.

“Let’s see, he was originally captured on August 28, 1979,” Dan Odell is telling me over the phone. Now a senior research scientist at Hubbs-SeaWorld Research Institute, in Orlando, Odell, 63, christened Dolphin 56 while conducting a U.S. National Marine Fisheries Service survey of dolphin populations in northeast Florida’s Indian River Lagoon system, an Atlantic estuary in the shadow of the Kennedy Space Center.

“On that day, we captured five dolphins,” Odell says. “We were in boats and used a long seine net in shallow water to encircle them. Then we drew the net tighter and tighter.” At the time of this first capturewhen Dolphin 56 was netted along with dolphins 55, 57, 58, and 59he was seven feet nine inches long and weighed roughly 320 pounds. After recording weight and measurements, Odell and his team numbed a portion of Dolphin 56’s jaw and pulled a tooth. Its growth pattern indicated that he was about 12 years old.

After that, Dolphin 56 got branded and released. “We used a brass branding iron, in his case with the number 56 on it, that was supercooled in liquid nitrogen,” Odell says.

In those days, no one had reason to believe Dolphin 56 would behave differently from any other dolphin in the study, all of whom were most likely lifetime residents of the lagoon. For 17 years he stayed put. He was sighted dozens of times in the estuary and was recaptured by Odell and his colleagues twice in the first three years, for measurement updates.

But even then Dolphin 56 had his own ideas. “For a few years, he used to hang out with another dolphin,” Odell says, “but something happened. And soon we never saw him, or even heard about him, with any other dolphins. Usually male dolphins live in pairs or groups of three, called alliances. But not 56. He became solitary. Which isn’t, like, totally unique. But it’s close.”

AT SOME POINT in the early eighties, boaters in the lagoon started reporting that Dolphin 56 was following boats and begging for fish. As he grew bolder, he often put his head and snout on the edges and low decks of their vessels. Soon he had put together a program of flips and splashing leaps that came to precede his appeals for food.

In November 1996, Dolphin 56 earned his first newspaper mention, a photo and caption in the Orlando Sentinel. Shortly after thatand for reasons still not clear to anyone but 56 himselfhe decided to take his show on the road.

“When a solitary male dolphin breaks off on his own, nobody knows quite whyand it’s probably a different story in every case,” Odell says. “Maybe there was a social struggle. Maybe he became an outcast. Maybe he just liked his own company.”

In the late nineties, biologist Sally Murphy, of the South Carolina Department of Natural Resources, told Odell that she’d seen reports of people spotting Dolphin 56 near Hilton Head Island. He was moving north, still well within his species’s normal range but a rare behavior nevertheless, since most bottlenose don’t travel far over their lifetimes. He was moving on his own scheduleand with his own agenda. Soon he was reported in waters off the Carolinas, Virginia, and Maryland, where he regularly entertained people in boats.

For Barry Truitt, a biologist with the Nature Conservancy who saw Dolphin 56 in 2002, the big moment came as a complete surprise. “We were in the Atlantic off the Virginia coast, in the channel off Hog Island,” Truitt says. “All of a sudden, this dolphin began putting on a SeaWorld show. He was tail-walking and making loud vocalizations really working to attract our attention. Then the damnedest thing happened. He swam right up to the boat, put his head on the gunwale, and began making pops and clicks with his mouth open, begging for food. Later, back at the office, I was telling people what had happened and someone said, ‘Oh, you just saw Dolphin 56.’ And I was like, Huh?”

Every summer from then on, Dolphin 56’s interactions have been recounted in small-town newspapers up and down the Atlantic coast. Which is how I first heard about him. A typical entry was this South Jersey Courier-Post story from August 20, 2001:

ENCOUNTER WITH DOLPHIN MAKES FISHERMAN’S DAY

In the words of Al Musico, an Ocean Beach resident who encountered a famous dolphin, “It was a dull day of fishing with a spectacular ending.”

On a recent Sunday afternoon, Musico was in his boat about 200 yards off the coast of Island Beach State Park just outside the Barnegat Bay inlet. Musico saw Dolphin 56 and ran below deck to get friend Ken Ernst and his son Michael Ernst.

Musico said the dolphin swam up to the boat and lifted his head out of the water, about a foot from the boat. The dolphin made typical “dolphin” clicking noises as if he were begging for food, and swam away after about five minutes when he saw he would get no food.

“It’s unmistakable who he is when he comes bounding toward you,” says Keith Rittmaster, natural-science curator for the North Carolina Maritime Museum. Rittmaster, 52, claims “a dozen or more” Dolphin 56 encounters. Along with Dan Odell, he makes up the hub of the Dolphin 56 information network, a loose group of half a dozen hardcores who stay connected by e-mail and phone. The network’s filaments extend to hundreds of people who’ve reported sightings over the years, Rittmaster says. “But when we get a flurry of Dolphin 56 sightings, wow, the number of people communicating sometimes spikes huge.”

To Rittmaster, seeing Dolphin 56 never gets old. “He engages you. When you think about it, what other large wild animal does that? Wild bears don’t approach people. Wild moose don’t. And while reinforcing begging behavior in wild dolphins shouldn’t ever be doneit leads to them being injured by propellers and colliding with boats and sometimes being inadvertently hurt by the humans themselvesDolphin 56 is a very unusual case.”

Rittmaster wonders whether there’s more going on with 56 than learned, food-motivated behavior. He recalls a day when the big guy swam up to his boat and, as usual, started begging. Federal law prohibits people from feeding wild dolphins, so Rittmaster couldn’t do much more than smile and shrug.

“After a few minutes, when he realized he wasn’t going to get any fish from me, heand this is no kiddinghe swam off, caught a fish in his mouth, then returned with the fish sticking out to show me,” Rittmaster says. “He was saying, ‘Feed me fish! I want fish from you!’ Obviously, he was capable of catching fish for himself. So what’s another explanation for his behavior? I mean, it sort of implies he wants interaction with people.”

ABOARD THE PHYLLIS ANN, as we motor into the broad Atlantic, our search gets down to business. Along for the ride with Houck and me are his wife, Phyllis, the boat’s namesake, and their 15-year-old daughter, Alicia. While Captain Rod and I scan the ocean for signs of dolphin life, Alicia is belowdecks, happily texting the day away. Phyllisa friendly woman who’s made sure we have food and cold soft drinksrelaxes in a deck chair, taking in the sun.

Houck and I keep looking, our heads on swivels. A sturdy, gregarious type, he chatters nonstop as he guides his vessel northward, tapping the throttle from time to time, giving the steering a tweak. Along the beachfront in the state park, groups of people line the sand, participants in the annual Governor’s Surf Fishing Tournament.

“There’s lots of people out today,” Houck says over and over. “Lots of activity out here. That should attract him. The seas are just right. If he’s gonna show, today’s the day.”

A union carpenter and lifelong fisherman from Yardville, New Jersey, Houck has the steady focus of someone who truly works for a living. He started his own Web site a few years back, calling it NJ Saltwater Fisherman, and it now has thousands of active members and numerous regular advertisers. I heard about his encounter with Dolphin 56 on the site after being directed there by Dan Odell. Two days later I contacted Houck, who understood my craving and invited me aboard for a 56-spotting expedition.

It’s a lazy afternoon, livened up briefly by Houck’s friend Ken Jelnicki, a fisherman and tinkerer who’s called Houck’s cell to let us know he’s about to use his newest invention, the Surf Rocket.

Consisting of a length of two-inch acrylic tube connected to a trigger-operated air tank, the Surf Rocket is a “mechanized surf-bait delivery system” that shoots a packet of frozen bait and chum 300 yards out into the ocean, with a fishing line attached. There it sinks, thaws, and releases a fish-attracting offer of chum and rigged, weighted baitfish, all well beyond the murk of the surf zone. Today Jelnicki is using it to assist a group of wheelchair users taking part in the fishing contest.

Houck says Jelnicki sets a rigged baitfish in a mold, then fills the rest of the container up with chopped fish and water. After that, it goes in the freezer. Eventually, he cuts away the mold and has a frozen cylinder that fits inside the Surf Rocket.

Houck smiles. “Ken’s a really, really nice guy,” he says, his eyes never leaving the ocean. “But he’s obviously single. I mean I don’t know any married guys who’d be allowed to keep a freezer full of baitfish in the house.”

Pooooof. On the beach, a white cloud of compressed air explodes out of the tube. The frozen parcel lands about 40 yards off the Phyllis Ann’s stern. Houck speed-dials Jelnicki on his iPhone. “Uh, Ken, that one was a little close,” he says. “We don’t want to get clocked out here.”

The hours spool along. We keep motoring north, past miles of state park, past the town of Seaside Park, past a surfside amusement park with its gray-planked boardwalks empty, its attractions and Ferris wheel already closed for the season. The trip is slow, the sun warm. Conditions for Dolphin 56 couldn’t be more perfect. And yet he’s nowhere.

“You know,” Houck says as the day dribbles on, “and this is something I forget about the ocean every time until I get back onto it. But the sea is really big it’s a huge area to search for a single animal. I mean, that’s something we gotta remember. The ocean is huge.”

DOLPHIN 56 MAY BE a loner, but he’s not the only quirky, friendly dolphin around. As Houck observed, it’s a big ocean out there, and over the years, at various spots around the globe, a number of dolphins have decided to break from the pack and become people-centric free agents. In March 2008, researchers with a British environmental group called Marine Connection published “Lone Rangers,” a report on solitary dolphins and whales. Authors Lissa Goodwin and Margaux Dodds found 91 examples, providing locations and episodes of human contact, as well as a behavioral framework for how these relationships evolve.

Goodwin and Dodds explained that most soloists appear to initiate human contact after arriving in a new home range. Once acclimatized, they start to follow boats, sometimes exhibiting leaping behaviors to attract attention. Eventually they grow confident, trying to interact with people as they ride in boats or swim; in some cases, this stage lasts for years.

Usually, the interactions are harmless. Friendly dolphins simply become attractions or, at worst, nuisances. According to “Lone Rangers,” a dolphin named Opo lived in Hokianga Harbour, New Zealand, in the fifties and chose to play gently with children. In 1975, in Key West, Florida, a female called Dolly befriended a family, allowing the kids to pet and play with her. In 1988 another dolphin, Billywho lived in the Port River outside Adelaide, Australiagrew fascinated by a horse trainer who exercised his animals every day by having them swim behind his small boat. Before long, Billy was swimming among the horses at every outing, often brushing against them. Between 1998 and 2004, Paquito, a male in San Sebastián, Spain, came within a few feet of swimmers, often putting on elaborate greetings for people he recognized, though he never allowed anyone to touch him. And in Ireland’s Dingle Bay there lives a dolphin named Fungie who’s been enjoying confabs with swimmers since 1984.

Then there’s the story of Moko, who lives off the Mahia Peninsula, in New Zealand. Since 2007, he’s interacted with children, providing “fin tows” around his native beaches. In March 2008, he assisted in the rescue of two pygmy sperm whales who’d stranded themselves in shallow water. After multiple attempts by humans to free them, Moko led both whales into deeper waters.

Unfortunately, a small number of these “friendly” individuals get so comfortable that they display sexual or dominance behavior toward people, sometimes with embarrassing results. In the late seventies, a dolphin named Donald, who cruised around off the coast of Cornwall, in southwest England, “permitted swimmers to hold his dorsal fin, taking them for tows ” But now and then, like the creepy guy in a city park, he “exhibited arousal,” pinning swimmers to the seabed while wriggling on top of them. In a 1994 incident, a previously friendly bottlenose dolphinTião, based in the Atlantic waters off São Sebastião, Brazilrammed and killed a swimmer and injured several others. For some reason, affable relations escalated into violence. Tião disappeared in 1995.

And sometimes, of course, the dolphins get hurt. Since 1990, a solitary male named Beggar has been studied south of Florida’s Sarasota Bay by Randall Wells, manager of the Sarasota Dolphin Research Program at the Mote Marine Laboratory. Beggar often approaches people, and he’s been able to avoid the dangers of fishing gear, boat hulls, and propellers. But his behavior has been modeled less successfully by others in the area. One four-year-old bottlenose dolphin died six weeks after he was first observed begging for food from humans. When his body was recovered, it had enormous propeller cuts on its tail stem.

At some point, even Dolphin 56 may have run afoul of humans. “A few years ago,” says Dan Odell, “photo images of him showed his lower jaw was no longer aligned with his beak, or upper jaw. He might have misjudged a boat and collided with it. Maybe he was injured in a human interaction. Maybe his jaw got broken or dislocated. We don’t know.”

Still, Odell says, Dolphin 56 “appears to be thriving. He’s a big, robust dolphin these days. He’s somewhere in his forties now. We don’t know where he goes in the wintermaybe into the Gulf Stream, but he never comes back to Florida. I have all these questions. Is he still sexually active? Why has he chosen to spend his life traveling?”

Odell says Dolphin 56 has carved out a bountiful life for himself, outliving the members of his original group. “The average age of a bottlenose dolphin in the Indian River system is 20 to 25 years old,” he says. So, right there, Dolphin 56 is well ahead of his old compatriots. It’s a life that seems to suit him.

LATE IN THE AFTERNOON aboard the Phyllis Ann, Dolphin 56’s panache has never been in question. “Seeing him two weeks ago was just so cool,” Houck is saying. “He was so friendly. He surfaced about there”he points at a spot two feet off the starboard side”and you could tell he was happy, and really healthy-looking. And he was huge. I’ll bet his body was as big around as a 55-gallon drum.”

But today it’s not to be. After five hours of perfect weather, a storm front has pushed in from the northeast, bringing spitting drizzle, a brisk wind, and falling temperatures. With the offshore breeze, a healthy chop has formed on the Atlantic’s surface. In these conditions, it would be hard to see Dolphin 56 even if he wanted to show himself.

Houck, adjusting to conditions, has shifted tactics. As we motor along the shore, he occasionally kills the engine and we drift while we pound the outside of the hull with our palms. Last time, Houck says, Dolphin 56 swam off toward another boat after his initial visit. By slapping the hull, Houck and his friends were able to call him back.

But even as he scans the sea and pounds on his boat, there’s anxiety in Houck’s voice and weariness behind his blue eyes. Sometime after 3 P.M., it’s decided: The day’s recon is over. As Houck pushes forward on the Phyllis Ann’s throttle and starts to steer us back south, he becomes philosophical.

“The GPS says we ran 47 miles today,” he says. “We got up and down the coast, we hit everywhere he’s been reported in the past few weeks. Had Dolphin 56 been here, and had he wanted to meet, we’d have found him. That’s a disappointment, you know? I had really high hopes but, then, I’m a high-hoper.”

Houck remains upbeat. He’s already talking about his next search: maybe trying again later this week, or certainly next weekend. As he talks, free-associating about the dolphin that’s become his fixation, I see that the contented (if distracted) mask of yet another Benign Ahab has settled pleasantly across his face.

“I’m pretty sure we can get out again next Sunday,” he’s saying. “If the weather stays warm, Dolphin 56 should still be hanging around.” Houck seems ready for the long haul, and he’s grasped a truth known to all Benign Ahabs. “Anytime you go searching for Dolphin 56,” he says, “you gotta remember: You don’t find him. It’s Dolphin 56 who always finds you.”