There is a route in my local climbing gym called Olympic Training 2020. It appeared in early August, as the gymnastics competition in London was wrapping up and track was hitting full swing.

Better start working out.

Better start working out.It’s worth mentioning here that my gym isn’t one of those modern complexes with yoga classes and hordes of 5.14 climbers tearing up the walls. It’s a small, worn-out, two-room building in a repurposed industrial park near downtown Santa Fe. The fact that Olympic fever has made it this far is a sign that climbers have got it bad.

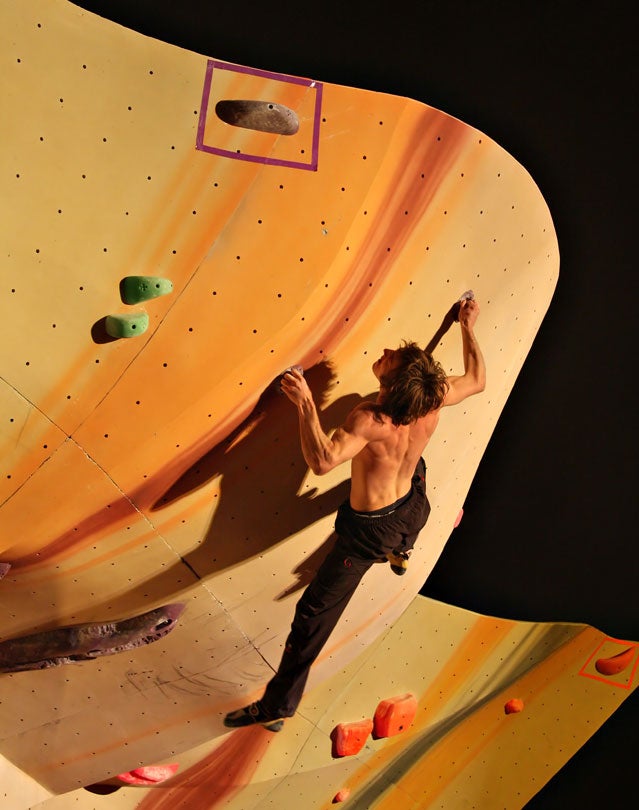

As far as climbers are concerned, you can forget Rio. The 2020 Summer Games are the next Olympics that matter. That will be the , assuming it beats out baseball, softball, karate, roller sports, squash, wakeboarding, wushu, and beach soccer (which it should; more on that later). The community as a whole is buzzing about the possibility that their sport could be in the Games, discussing it at World Cup bouldering competitions, around campfires, and in climbing media. As the photo on the left shows, even tiny gyms in New Mexico aren’t immune.

Of all the basic forms of movement we inherited from our ape ancestors, none has gotten such short shrift from the Olympics as climbing. Throwing has the shot put, the javelin, the discus, and the hammer. Jumping has the long jump, the high jump, and the triple jump. Runners compete in 15 different individual events and relays. Climbing? Apart from the rope climb, which appeared sporadically from 1896 to 1932 as part of the gymnastics program, and a handful of medals awarded for achievement in mountaineering during the 1920s, it’s been completely absent.

Part of the reason for climbing’s omission is cultural. In the early part of the century, when much of the lineup of the modern games was codified, the scene was dominated by alpine climbing, a long game that emphasizes tactics, endurance, and guts over athleticism. Rock climbing pioneers of the 1950s and ŌĆś60s like Royal Robbins and Layton Kor were cut from the same cloth, explorers who used gear-intensive aid-climbing techniques to pioneer big walls.

But all of that changed in the 1970s with the shift toward free climbing, a discipline in which climbers ascend the rock by grabbing and pulling holds instead of relying on artificial aids. A young German named Kurt Albert revolutionized the sport when he began to methodically practice routes in Bavaria’s Frankenjura until he could do them using only his hands and feet, a process now known as redpointing. John Bachar, who would become famous for his bold free solos in Yosemite, studied exercise science and weight-trained until he could do a one-arm pull-up holding 12 and a half pounds in his free hand. Climbers became athletes whose success depended as much on finger strength and footwork as it did on mental toughness. Thirty-odd years later, the majority of young climbers learn the sport in indoor gyms, and top pros battle it out in World Cup competitions broadcast on both television and the Internet.

The International Olympic Committee acknowledged climbing’s changed face in 2010, when it recognized the International Federation of Sport Climbing, making the sport eligible for the Games. Climbers will find out if they make the cut in September 2013, when the I.O.C. meets for its 125th session in Buenos Aires. In the meantime, both they and the committee will be closely watching the 2012 World Championships in Paris, which kick off on September 12, to get a sense of how an Olympic climbing competition might play out.

What sets the Olympics apart from other tournaments like the NFL playoffs or World Cup is their role as a showcase of raw human ability. Michael Phelps crossing a pool in a tenth of the time it would take a normal person. Usain Bolt running fast enough to break a residential speed limit. We remember the moments when athletes do things that human beings shouldn’t be physically capable of.

Watching a world-cup climber in action is like seeing some strange hybrid of human and gecko. Top competitors like Sachi Amma and Kilian Fischuber can climb an overhanging wall on razor-thin holds or jump and catch themselves by two fingers. The competition doesn’t rely on contrived rules or subjective judging: the person who gets to the top wins. Tell me that isn’t more exciting than watching squash.

Of course, the I.O.C. has more practical concerns. They want sports that can bring more viewers, sponsorship dollars, and media presence to the Games. Climbing wins on those counts too. The sport has a huge, single-minded fan base around the world; last year’s world championships in Arco, Italy, drew athletes from 60 countries and thousands of fans. Getting their attention could be the key to drawing in big-name sponsors like and which would otherwise have little reason to bring their clout to the Games. Olympic climbing would be the sport’s top event, rather than being eclipsed by a larger, more lucrative pro competition (remember the last World Baseball Classic? Neither do we).

While we won’t find out the I.O.C.’s decision for another year, there are reasons to be cautiously optimistic about climbing’s chances. Ice climbing will appear for the first time as a demonstration sport in the 2014 Sochi Olympics, and while the Olympic committee has picked some outlandish demonstration sports in the past ( and kite flying both appeared at the 1900 games), it might be a signal of the organization’s willingness to give climbing a second look.

On a larger level, climbing is at an ascendant moment in its history. and are profiling Alex Honnold, boulderers have appeared on , and the Unified Bouldering Championships has held competitions in the middle of Central Park. We’re already getting a sense of what the Olympic climbing field might look like in young guns like Ashima Shiraishi, the 11-year-old who has climbed V13 and won her age group at national competitions, and Enzo Oddo, the French climber who at 17 years old is sending routes near the upper edge of the grade scale. Maybe some kid from a little, run-down gym in Santa Fe will end up joining them in 2020, if the I.O.C. sees fit to give them the chance.