THE DAY DRAINS like sluggish water out of the Alakai Swamp. We are woefully late and losing speed. Bill DeCosta, a local boar hunter and guide, hacks out a trail with a machete dulled from hours of cutting through vigorous cellulose. The air is cool and still. There’s a threat of rain—but only a threat. A strange blue hole in the sky has hovered above us all through the swamp, like the reverse image of a tiny cartoon cloudburst following some sad character down the street. The blue hole mocks us. We came here to find rain. The rain has decided it doesn’t want to be found.

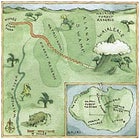

Middle earth, schmiddle earth: The view down the Wailua River valley, the impenetrable approach to Waialeale on Kauai’s east side

Middle earth, schmiddle earth: The view down the Wailua River valley, the impenetrable approach to Waialeale on Kauai’s east side Swamp Thing: Bill Decosta displays his Egyptian pharoah hound tattoo. Boars are “nasty varmints,” he says.

Swamp Thing: Bill Decosta displays his Egyptian pharoah hound tattoo. Boars are “nasty varmints,” he says. “All the sinister powers of the earth are against you”: The great ridge path of kane as it ascends Waialeale’s misty peak.

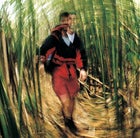

“All the sinister powers of the earth are against you”: The great ridge path of kane as it ascends Waialeale’s misty peak.

Tangled up in green: Caught in the scraggly cluthes of Alakai, the writer works his way toward a better understanding of da aina

Tangled up in green: Caught in the scraggly cluthes of Alakai, the writer works his way toward a better understanding of da aina Bill sets down the blade to give his wrists a rest while I scramble up the trunk of a lehua tree that’s leaning like a universal NO slash across the ridgetop. My mind is on the time. What is it—three o’clock? Four? We’ve been stomping through dank, murky jungle to an unfamiliar rhythm. Our turnaround time has come and gone. We need to see the summit—now.

Thirty feet below me, Bill and my partners—Skip Card, an old skiing and climbing buddy, and Kike (pronounced “KEY-kay”) Arnal, a Venezuelan photographer with extensive experience in the Amazon rainforest—await good news. There’s none to deliver.

“Sorry, fellas,” I call out. “Miles and miles of same.”

The swamp ascends into the perpetual mist of Waialeale, the 5,148-foot extinct volcano at the center of Kauai, the lushest of the Hawaiian Islands. I shimmy down and slump to the ground. My legs are crosshatched with slices and scratches, but the pain comes from somewhere deep in the gut, where pride resides. This is failure, served cold. It arrives not as a dramatic mishap—that would be too face-savingly easy—but as the realization that you planned for months and came up pitifully short. Pressing on would not be courageous but foolhardy.

It’s late February, perhaps the least wet time—and thus, the best window of opportunity—to attempt to reach the wettest spot on earth. In an average year, more than 460 inches of water collects in the U.S. Geological Survey’s rain gauge on the summit of Waialeale (locals waffle between “WHY-ollie-ollie” and “WHY-lay-lay”). That’s 38 feet of rain.

It’s easy to get near Waialeale. Every year more than a million tourists come to hike the zigzag cliffs of the Na Pali Coast, snorkel with parrot fish, and lounge poolside in dozens of posh resorts that lie within 12 aerial miles of the summit. It is extremely difficult, however, to reach the peak itself. Of those million-plus visitors, the number who actually make it to the wettest spot on earth is zero. And the number of living islanders who have stood atop Waialeale can probably be counted on your fingers and toes.

The mountain rises straight up out of the east side of Kauai, a spectacular 5,000-foot headwall set back about ten miles from the coast, dripping with ferns and moss. On the west side, it slopes down into the Alakai Swamp, a dense, 34-square-mile rainforest teeming with wild boar, lehua trees, fan palms, 15 fern species, and some of the world’s rarest plants and birds, including Melicope paniculata, a species of the alani, a flowering citrus shrub (of which only 110 are known to exist in the wild); and the ‘o’o, a bird that hasn’t been seen in more than a decade. So cloud-shrouded that its summit appears only about 20 days a year, Waialeale stands as the most inscrutable peak in the United States.

We take a GPS reading and map our position. At this rate, it will take two more days to reach the summit. If we continue on without Bill, we will get lost as surely as the sun will rise tomorrow. If Bill continues on with us, he could lose his day job down in the harbor. “I could call in sick,” he offers. As soon as he says it, we all realize it’s out of the question. We look at one another.

Three of the hardest words you’ll ever hear: We turn around.

But in defeat we gain something more valuable: respect for da aina .

I LIVE IN SEATTLE, a city famous for its wetness. From November to June, the constant drizzle turns western Washington into a damp basement with too few windows. Though I was born and raised there, each winter the rain becomes a little more intolerable. Moisture seeps into the skull and rots the mind. Moss grows in the lee of my car’s sideview mirror. The whole world feels itchy.

And yet, for some unhinged reason, I wanted to see rain at its worst. The peak of Waialeale promised the sorriest, soggiest atmosphere on the planet. But experiencing it required getting to it. Make inquiries about how to reach Waialeale and you’ll encounter descriptions of impregnability not heard since Lawrence of Arabia took briefings on Aqaba. “We don’t go there, and neither should you” is the constant refrain. But among the sportsmen and guides on Kauai whom I talked to, there was one man who knew the pig-rooting backcountry of the Alakai Swamp better than anyone. They called him Wild Bill.

“You’re looking at a third-generation Hawaiian boar hunter here, Bruce,” said Bill DeCosta the first time we met. I could tell. He was standing under the head of a 175-pound Polynesian pig, one of six tusk-hogs mounted on the living room wall in his suburban rambler tucked into the foothills above Kalaheo, on Kauai’s southern coast. Bill is 36. He works as a longshoreman on the docks of Nawiliwili Harbor and has been hunting in the swamp since he was seven. “Some guys hunt. Ah, but Billy,” DeCosta’s friend Jarvin Peralta told me, “Billy gotta hunt. It’s in his blood.”

Bill had cultivated a look all his own: jet-black mullet, Fu Manchu mustache, Frank Zappa-esque lower-lip soul patch. He wasn’t tall, an asset when bushwhacking through hairy foliage. He preferred to dress in fatigues. He spoke in a mellifluous blend of college-educated English and island patois, and his left shoulder bore an elaborate tattoo of an Egyptian pharaoh hound, the breed of dog he uses to hunt wild boar. In the Alakai Swamp. Armed with only a Rambo knife. In the dark.

Bill told me a bit about himself as he fried up some wild boar tips on his kitchen stove: that he was born and raised on Kauai but comes from Portuguese stock; that the money his father saved by bringing home wild-pig meat helped put Bill through Humboldt State University in California; that once his dogs corner a boar, Bill finishes it off with a knife thrust behind the front shoulder; that he carries the kill out of the bush by wearing it like a pig backpack; that he trades ham and bacon with his friends and relatives for island-made salt, island-caught fish, and island-grown fruits and vegetables, as part of an extensive barter economy that blunts the high cost of living in a tourist preserve.

He wasn’t sure what to make of me, so he called his brother to see if he wanted to join us. His brother was skeptical. “My bruddah wants to make sure you’re not some environmentalist who wants to go back and discover some rare birds and plants,” said Bill.

I assured him I was not. State and federal agencies are under a court order to designate portions of the Alakai Swamp and nearby Waimea Canyon—38,000 acres in all—as critical habitat for more than 70 rare native plants listed as threatened or endangered during the 1990s. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service initially declined to map out the critical habitat areas because it didn’t want to provide directions for rare-plant thieves. Environmental groups took Fish and Wildlife to court in 1997 and won, and now the habitat areas are going forward. Habitat designation puts up an additional roadblock to development but doesn’t restrict hunting. Kauai’s hunters and environmentalists get along better than most, because the hunters kill the feral pigs that root up the rare plants. Still, Bill and his fellow sportsmen suspect this could be the first step toward kicking the local people out of the swamp altogether.

“The white man with the money, he’ll come and buy his safe haven,” Bill told me. “I can barely afford this home I’m on right now. So my safe haven is using da aina—the land.”

Although willing to lead me, Kike, and Skip into the swamp, Bill remained dubious about our chances of making it to the summit of Waialeale, which even he had never seen.

“Would be so easy to get lost back there, brah,” he said. “Everything looks the same.”

Yes, I said, but we have a plan! Starting from Kokee State Park, on the west side of Waialeale, we would drive as far into the Na PaliÐKona Forest Reserve as the rutted forest road would allow, then hike an unmaintained trail east through the Alakai Swamp to its closest point to the peak, and from there bushwhack our way up to the summit. If my USGS topo map could be trusted, we were looking at a round-trip of 40 miles, 18 of them on foot, and an elevation gain of just over a thousand feet. Barring any snafus, we could make it in, up, and back out in three days, or two very long ones.

It looked good on paper. But not to Bill. “Bruce,” he said. “Realistically speaking? Your mountaineer people who go to the Cascades? They’ll spend months back there, they don’t know where they going.”

“Skip’s bringing a GPS unit,” I piped up.

“Never worked with GPS,” said Bill. “Only GPS is what I got up here.” He tapped his temple. “I work with pink ribbon. Find my own way back.”

“What’s the main concern?” I asked. “The clouds coming down?”

Bill nodded. “You on the wettest spot in the world. That cloud cover come in, this time a year. Cold. Wet. Blind. Be pretty miserable, Bruce.”

We finished off the boar tips, which tasted like the ham they serve in heaven, and Bill called his boss down at the docks to see if he could swing three days off. He got two. We agreed to meet before dawn two days later and give it our best shot.

BACK WHEN EXTREME SPORT was known simply as pilgrimage, Hawaiian chiefs and priests undertook the arduous trek to Waialeale to pay homage to Kane, the Hawaiian god of fertility. After a day’s paddle up the Wailua River on the island’s east side, the royal party abandoned its canoes to ascend the Kuamo’o-loa-a-Kane, or Great Ridge Path of Kane, a slippery, knife-edged goat trail. As they crested the summit, they entered an eerie landscape. Thick clouds swirled about the barren peak, often trapping the visitors in a cold, blinding whiteout. Fierce winds threatened to blow them over the lip of the crater. The mighty lehua trees that grew big as houses on the coast struggled here to reach the height of a man’s knee. They knelt to drink from a small pond whose wind-wrinkled surface inspired the name Waialeale (“rippling waters”) and scattered their offerings around a seven-foot-long heiau, or altar, that still stands not far from the pond. Then they got out of there.

In 1874, George Dole—whose cousin founded the Dole Food Company and whose brother, Sanford, was appointed the first president of the Republic of Hawaii after helping to depose Queen Liliuokalani in 1893—became one of the first non-Native Hawaiians to climb Waialeale. “Were it not for the thick tangled growth of trees and vines and bushes which cover this pali [cliff],” he wrote, “it would be utterly impossible to ascend.” Dole returned bruised, lame, and cut up.

Kauai historian Eric Knudsen, who ascended in 1902 before the jungle reclaimed all trace of the Great Ridge Path, provided a similarly inspirational endorsement: “It’s wet, awfully wet, and you get soaked and it’s cold and you feel that all the sinister powers of the earth are against you.”

So I’d come to the right place. But these accounts were a hundred years old. In search of a more up-to-date report on the mountain’s condition, I turned to Tom Schroeder, head of the University of Hawaii’s meteorology department and author of a 1999 study of Waialeale’s rainfall patterns. “The terrain’s boggy, the trees are stunted, and most of the plants don’t look green because they don’t see enough sunlight,” he told me. “The USGS flies a chopper up there every few months to check the rain gauge. They don’t land, they hover. If they landed, they’d sink. It’s quite dangerous. They’re flying in along the ridge, and the clouds often close in. In the old days, the USGS guys read the rain gauge by hiking in through the Alakai Swamp. Took ’em days. One of them died on a trip once. Went in and never came out.”

Waialeale, it turns out, is a diabolically perfect weather machine. After cruising over 2,000 miles of open Pacific, warm northeasterly trade winds sweep up the mountain’s ridges and create an updraft so constant that helicopter pilots can maneuver their craft like gliders in its slipstream. The moist air cools as it rises, reaching dewpoint at about 3,000 feet and dropping a constant scrim of mist on the upper reaches of the caldera. The mountain’s nearest “rainiest spot” rival, the village of Cherrapunji in northeastern India, receives most of its 450 inches of rain in monsoon bursts that can be terrifying in their ferocity. Waialeale, on the other hand, produces some of the gentlest rain on the planet. It’s just that it hardly ever stops.

“HOLD ON NOW, FELLAS,” says Bill, and we plunge to the bottom of another man-eating puddle. Two days of hard rain have left the road to the trailhead impassable to all but a few overbuilt four-by-fours. As Bill’s Super Swamper tires churn through the muck, Kike, Skip, and I pinball around the cab of his truck, a Ford F-150 XLT customized to survive Kauai’s gloppy red-dirt interior. We pass three biologists radio-tracking rare birds and stop to greet two bedraggled German hikers.

“Hey!” Bill calls out. “You guys see any wild boar around here?” Hans and Franz respond with puzzled looks; they can’t break the language barrier. “Wild! Boar!” Bill yells, as if volume were the problem. They smile, shake their heads, and flash us a shaka, the Hawaiian “hang loose” hand signal.

“I’m not into killing mammals,” Bill explains as we bounce down the road. “I love to see a deer in a national forest. But there’s nothing nice about a boar. It’s a nasty varmint. Got those overgrown tusks. Do you know, Bruce, when they swing their head from side to side, those tusks are moving at 70 miles an hour? I lost three dogs to the boar last year.”

The mud track ends on a bluff overlooking the Alakai. A series of green ridges and valleys unrolls before us like furry waves. Somewhere in the distance lies Waialeale. We’re already running late—road’s a bitch, brah—but the freaky blue hole overhead portends quick passage to the fogbound summit. The state has erected a wooden sign at the trailhead. THERE IS NO TRAIL TO WAIALEALE, it announces, as if giving us fair warning. Somebody has scratched off the no.

“Very few guys hunt this area,” says Bill. “Number-one reason, it’s hard to get your bearing when you’re hunting back there. Lotta hunters are afraid of that. And not many people have a good sense of direction. One thing I was given as a gift—my dad had it, my granddad had it—is a sense of direction. You’ll see what I mean when we get back there.” The deceptions of the Alakai Swamp begin with its name. “Swamp” seduces you with visions of a low, boggy country, something that might breed thick-skinned reptiles or poorly educated men named Cooter. It’s wet, all right—where the water hasn’t collected in brown pools, it lies hidden under a matrix of rotting vegetation. But flat it is not. The swamp rises up to Waialeale over steep ridges that are choked with the gnarled limbs of lehua trees, Brobdingnagian tree ferns, and the bladelike fronds of the uluhe plant. For every step you take there’s a root to trip you or a vine to wrap around your neck or an overhanging branch to clobber your skull.

We push through anyway, the forest effervescing around us like a Pleistocene bathhouse. Our immediate goal is to stash our sleeping gear at one of Bill’s secret hunting camps (secret because the state frowns on such incursions), then make our fast-and-light dash to the summit. After the first bridgeless river crossing, however, the trail disappears. Four exhausting hours later, Bill suddenly comes to a halt. “We cut right from here,” he says. Only there’s nothing to the right but open air.

No matter. Bill plunges into an unmarked ravine, as if swallowed by the jungle. Skip, Kike, and I tumble and crash after him and end up shin-deep in a blackwater bog connected to one of the many rivers draining the swamp. We can barely make out Bill’s form through the seven-foot ferns. He stops atop a small knoll to take his bearings.

“Go back, Kike!” he calls out. “Try that otha way.” We exchange wary glances. Does this guy know where he’s going? More to the point, does he know where he’s at? Skip hurriedly punches the waypoint into his GPS.

“Wow. River came up high,” says Bill, pointing to the bath ring of woody debris left on the bank by the last flood. “Hope my camp’s still there.”

On a continuum of phrases you’d rather not hear from your guide, this sits somewhere between “You carry the tent” and “Play dead when he charges.” Bill takes the lead again, patiently slogging through the marsh and reading the land, confident that his senses will lead him home. After 20 minutes he spots a scrap of blue tarp peeking through the palm fronds. “This way to the DeCosta hacienda!” he yells.

Under a three-tarp lean-to, Bill has stashed all the comforts a wild-pig hunter requires: warm blankets, foam padding, a stove, a lantern, and enough Campbell’s Chunky soup to sustain a hungry man for a week. On a rope that anchors the shelter to a tree hang a T-shirt, a pair of denim cutoffs, and three socks, which, this being the doorstep to the wettest spot on earth, have become prosperous mildew ranches.

“I bring my young dogs here once or twice in the summer,” Bill says. “The pigs this far back in the swamp don’t have a lot of experience with dogs, so they’re easier to catch.” Two boar skulls hanging from a nearby branch testify to the effectiveness of Bill’s methods.

After dumping weight at this swampside Sheraton, we scramble back up the ridge and head for the peak. It took six hours, twice as long as we scheduled, to reach Bill’s camp. We press on into the swamp with the hope that the rainforest may give way to an open plain. It is a futile hope. The lengthening shadows hint at the coming arrival of failure. At which point our quest may become something else entirely.

YEARS AGO, historian Kirkpatrick Sale came across a Spanish term, querencia, while researching a biography of Christopher Columbus. “Querencia,” Sale wrote, “is the deep sense of inner well-being that comes from knowing a particular place on the Earth; its daily and seasonal patterns, its fruits and scents, its soils and birdsongs.”

The deeper we push into the swamp the more difficult it becomes for Wild Bill to contain his querencia. He stops every ten minutes to talk story. He recalls great storms and epic boar hunts, island lore and family tales. Meanwhile, I’m stealing impatient glances at my watch. Not to mention the sky. The blue hole, and the eerie absence of rain, suddenly puts me in mind of Joaquin Phoenix’s unctuous couplet from Gladiator: It vexes me; I am terribly vexed.

Bill uses this rare meteorological moment to give us a history lesson. “Long time ago when the sugar plantations were thriving,” he says, “the white people would settle disputes with workers by refusing to pay or feed them. So a few people came up here to the swamp to hunt for food. There’s a place across that ridge there called Rapozo Puka—Rapozo’s Hole—named for Jungalo Rapozo, who used to hunt up here. There were so many pigs back there, he fed most of the village in Pakala.”

Bill swipes at the trail with his machete and dresses a lehua branch with pink plastic ribbon.

“The swamp was a place the Hawaiians could go and nobody could reach them,” he continues. “In the 1890s, there was a gentleman named Cowboy Koolau. He had leprosy. They wanted to ship him to the leper colony on Molokai, but Koolau wanted to live out his days here on his home island. So he and his wife escaped up Kalalau Valley and into the high swamp. The white man sent in sheriffs to hunt this man down, a man of da aina, to bring him to Molokai.

“In the process Koolau ended up shooting a sheriff on one of the high ridges. Now he was wanted for murder. The president of the Republic of Hawaii declared martial law, sent soldiers after him with big guns.” Bill pauses. “They never found him.”

Koolau killed a sheriff and three soldiers and survived in Kauai’s swamps for three more years before dying of leprosy. Jack London spun the tale of the legendary outlaw into one of his most popular short stories, “Koolau the Leper.”

Three mud-caked, sweat-drenched hours from Bill’s camp, we reach what might be the secret spur to Waialeale. Bill isn’t sure. “Bruce, you go that way and give us a yell every 20 feet,” he tells me. That way? I step 20 paces off-trail and get the heebie-jeebies.

“CAN YA HEAR ME NOWWWWwwww?”

I might as well be shouting into a snowstorm. “I’ve only been out this far once, about ten years ago, before the hurricane,” Bill says when I come crawling back out of the bush. “Lotta stuff blow over, ah?” Thick trunks and branches crisscross the ridgetop. Where the rainforest hadn’t reclaimed the remnants of the old rain-gauge path, 1992’s Hurricane Iniki pretty much finished the job.

We muddle along behind Bill’s machete strokes but the tangle around us shows no sign of abating. We pick our way across a thin ridge that skirts a sheer 80-foot drop. I check the map: No such cliff. It seems that when the cartographers got this far into the swamp, they just threw up their hands and started doodling topo squiggles. “I wanna get back through this section before dark,” says Bill. Good thinking.

One hour and a few hundred yards later, I climb the lehua tree and deliver the bad news. We stumble back to Bill’s camp in the dimming light.

Bill puts a brave face on it. “I’m tellin’ you, Bruce, you came here on one a the rarest times a the year. Rains here alla time—but not today.” I’m realizing something else, though: The forest itself is the rain. Rain keeps the cliffs slick, the forest lush, overgrown, squishy. The Alakai Swamp is rain expressed as a green solid. The wettest spot on earth is guarded by a five-mile-thick cube of biomass that never stops growing.

THAT NIGHT, after cleaning out Bill’s pantry, the four of us sardine under a low-slung tarp. “Ah, this the life, eh fellas?” says Bill. “Nothing finer. When I think about the good times ahead in my life, I think about bringing my boy out here, showing him the land, teaching him about the plants, the birds. Hunt a little boar. But mostly just be out here.

“Have you heard of this lady who spent a year up in a tree, Bruce?” Bill asks. “Julia Butterfly Hill?”

“I think I mebbe do the same if it comes to it, with they fencing off they rare plants,” he tells me. “Disappear into the swamp. Let ’em come get me. I think we ought to save rare species, too, Bruce. But I come from an old family line that taught me about these things. The forest is always better left alone, ah? Mother Nature takes care of itself.”

Darkness comes and we drift off to sleep. In the middle of the night, I wake to hear a light rain brushing the tarp.