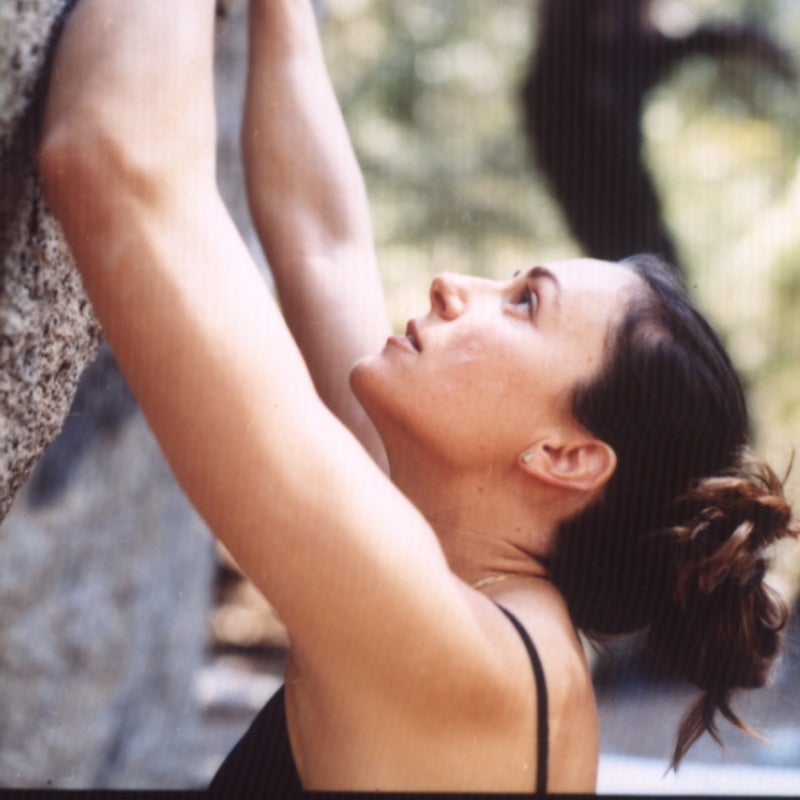

Steph Davis Rocks

Steph Davis knows the downside of being one of the world’s best women climbers: like living out of a car for seven years and having your mom suggest (frequently) that you’re out of your mind. The upside? Yosemite. The Andes. And a life in which every day is a thrilling vertical grab.

New perk: Easily find new routes and hidden gems, upcoming running events, and more near you. Your weekly Local Running Newsletter has everything you need to lace up! .

On a warm afternoon in late October 2005, El Capitan towers 3,600 feet above Yosemite Valley, gray and massive like a battleship propped on one end. Tiny yellow portaledges and speck-size climbers dangle off the granite face on invisible ropes. From this distance, the climbers appear motionless, all their toil swallowed up by the enormous scale.

Twenty-five hundred feet up, on the toughest move on one of El Cap’s toughest routes, is scraping at the rock with half-frozen feet when her right climbing shoe slips, and just like that she’s falling 30 feet through the air. Her rope snaps taut and she jerks to a stop, swinging in space. She yells down to her belayer, a 38-year-old woman named Cybele Blood, whom Davis recruited from Yosemite’s dirtbag contingent, to let her know she’s not hurt. She’s just annoyed.

“Great,” she mutters, knowing there’s only one thing to do: suck it up and keep climbing.

Davis is eight days into her attempt to become the first woman to free-climb the Salathé Wall, a 35-pitch route on El Cap’s prominent southwest face—and by her estimate she should be done already. But from the beginning, nothing’s gone according to plan.

For starters, there’s the weather. By turns blazingly hot, then sleety, windy, and cold, these are the kinds of erratic conditions that can turn ugly fast, as they did almost exactly a year ago, when a snowstorm hit El Cap, trapping two Japanese climbers who froze to death before rescuers could reach them. Davis isn’t equipped for that kind of weather. She’s wearing light rock shoes, climbing tights, long underwear, and a gauzy wind jacket. Her only other gear: a summer-weight sleeping bag, a tiny portable espresso maker, and not nearly enough food.

But her main problem is doubt, an awful, lurking worry that she’s simply outmatched by the Salathé's hardest pitch, 150 feet of flinty holds known as the Enduro Headwall. And that’s a bad sign, because Davis’s greatest assets aren’t natural athletic talent and flawless technique but sheer will and a brainy, methodical work ethic. The 33-year-old trained alone all summer for this climb, rappelling hundreds of feet off El Cap to practice the Salathé's hardest sections over and over. But leading a 5.13 climb—which is like spidering up the side of a skyscraper, clinging to crimps no bigger than a lentil—is a different story altogether, and Davis is falling. A lot.

Unlike traditional aid climbing, where it’s OK to hang off ropes while you scale a wall, free climbing requires that you use only your hands and feet to climb the rock’s natural cracks and flakes. Protective devices are there to catch you if you fall, as is your belayer. And while falling isn’t forbidden, it’s definitely inconvenient. Take a whipper off the wall and you have to lower yourself to the start of the pitch and climb it again, cleanly.

Davis has been stuck on this one section all day. Now, with daylight fading, she’s doomed to spend the night on a granite ledge barely wider than a diving board, 2,500 feet of vertical drop yawning beneath her. A thought crosses her mind: Why not just quit and go down?

The truth is, whether she succeeds or fails on the Salathé, not many people will know or care. Free climbing is a niche pursuit that most of the world doesn’t even understand. Davis is a sponsored professional—she makes a decent living through endorsements from Patagonia, Five Ten, Clif Bar, and Black Diamond—so she needs to keep performing at a top level. But she’ll never get rich or famous doing this.

And make no mistake: Davis, along with climbers like 26-year-old Beth Rodden and 45-year-old legend Lynn Hill, is among the all-time elite.

“Let’s just say,” she laughs, “that it’s not as lucrative as golf!”

In fact, the only people likely to notice are other climbers, which can be a mixed bag. Climbing is a small and sometimes snarky community, where everybody has opinions about everybody else. Davis earns plenty of praise—“She’s a superstar,” says alpine climber Mark Synnott—but because she’s sponsored, she hears plenty of secondhand griping that she’s sold out.

This may seem like skimpy payoff for someone who’s worked tirelessly for the past 15 years to become one of the best women climbers in the world. And make no mistake: Davis, along with climbers like 26-year-old Beth Rodden and 45-year-old legend Lynn Hill, is among the all-time elite. She’s put up first ascents on hellish alpine faces from Pakistan to Patagonia, freezing for days at a time in snow caves, nearly getting clobbered by falling chunks of ice, and rappelling solo down thousand-foot faces while her husband, 34-year-old pro climber Dean Potter, BASE-jumps off the top.

All this from a woman who grew up playing piano, not sports, never heard of climbing until the relatively ancient age of 18, but somehow had the nerve to quit law school to follow her dream, despite the fact that her parents routinely told her she was nuts. In the risk-versus-rewards department, do the rewards even come close?

I first met Davis in Moab, Utah, at the home she shares with Potter and their dog, a ten-year-old heeler mix named Fletcher. They’ve lived in Moab on and off for the past six years, but they’re rarely around. They spend the summer and fall free-climbing in Yosemite, where they own a couple of empty lots and plan to build a house. Come winter, they’re usually off on an alpine expedition in the Andes. Davis is accustomed to the nomadic lifestyle—during her long climbing apprenticeship, she lived out of her car for seven years—but Moab is where she comes to escape what she calls the “penury and suffering” of climbing and go into serious nesting mode.

It was a hot desert day, and we’d spent the past 24 hours doing the things a pro climber does when she’s not on the rock: trail-running, monkeying around on her homemade climbing wall, balancing on a slackline strung up in the front yard. We were just back from a hike through shin-deep snow in the La Sal Mountains and were sitting barefoot on the front steps, trying to relax.

Actually, I was trying to relax. Davis was busy rigging a drip hose to her potted pansies—“I simply cannot go to Yosemite until I fix my irrigation!” she declared—while debating how best to fix the trim around her front door with Ole Hougan, her sixty-something handyman. From the street, Davis’s squat one-story house looks snug and homey. Closer inspection reveals that the charming little cottage is, in fact, a double-wide mobile home.

“You know, when you live in a trailer, it really keeps you honest,” she said with a grin. “You should not have any kind of mess that doesn’t look good. Immediately, it’s trashy!”

Davis is preternaturally cheerful, prone to enthusiastic outbursts and an emphatic way of talking that sounds like shouting, only not as loud. At five foot five and 120 pounds, she’s lean and strong, with olive skin, quizzical eyebrows, boyish calves, and the energy of a coiled-up spring waiting to pop.

Inside the trailer, the first thing you notice is the ivory upright piano. Polished to a sheen and surrounded by oddball castoffs—a giant, flying-saucer-shaped wicker chair, a defunct woodstove—it glistens like a wedding limo. “At first I thought, I just cannot have a white piano,” said Davis, who bought it used two years ago. “But it had a nice sound, and I figured it would match the off-white carpeting and walls. It’s so my trailer!”

To understand who Davis is, it’s helpful to consider the piano.

To understand who Davis is, it’s helpful to consider the piano. Her mother, Connie, enrolled her in lessons when she was four, hoping to instill an appreciation for music and a sense of purpose. It worked. By the time Davis was in high school in Columbia, Maryland, she was practicing classical piano six hours a day and bringing home straight A’s. She was talented and focused but no prodigy, and it was understood that music was a means to an end—and the end was self-discipline.

“We never pushed Stephanie into anything, but we were academically inclined,” says Connie, who now lives near Tucson with Steph’s father, Virgil, a retired aerospace executive. “I just assumed she would go to college, get her law degree, and stay in a job forever.”

But Davis had other ideas. In the spring of 1991, during her freshman year at the University of Maryland, a guy she barely knew offered to take her rock climbing. She was instantly hooked. She gave up piano, exchanged for a year to Colorado State to be closer to the mountains, and then went back to Colorado after graduation to pursue a master’s in English literature. She climbed in her spare time: alpine routes on Longs Peak, in Rocky Mountain National Park, and bouldering trips to Hueco Tanks, in Texas. In September 1995, she enrolled in law school at the University of Colorado in Boulder, even though she didn’t want to go. A week later, she quit school for good.

Within a month, she’d built a bed in the backseat of her grandmother’s hand-me-down Cutlass Sierra and begun driving to climbing areas, waiting tables for cash. “It was a big shock,” says Connie. “We were just a regular family—climbing wasn’t something we could relate to, and Virgil and I weren’t going to enable her. She needed to find out what it was really like. She did it by herself, with no help from us.”

Through it all, Davis remained her geeky, systematic self. Though she made about $6,000 a year, she managed to open an IRA. She read constantly—everything from Gabriel García Márquez to Kirstie Alley’s autobiography (“That was embarrassing,” she admits) to French short stories she translated herself. But she never felt settled. “I was scared all the time,” she recalls. “My parents did not like my choices and thought I was doing stupid things with my life, and they told me so. I didn’t feel like anyone cared if I did a climb I was proud of. They were just like, ‘Great. What about your future schooling?’”

She labored for years, trying and failing on tough western rock routes like Pink Flamingo, a “really stout, horrible” 5.13b crack at Indian Creek, south of Moab, which she abandoned right away. “I thought if I couldn’t do a climb after two or three tries, I wasn’t good enough,” she says. “And then when I did do one, I thought it was a fluke.”

“Steph wasn’t the most supertalented at the beginning,” Potter agrees. “But she always kept pushing.”

Which brings us to the other thing you notice in Davis’s trailer: a handwritten quote, taped to the refrigerator at eye level, that reads, STRUGGLE IS PART OF LIFE, AND ONCE WE ACCEPT THAT, THINGS WILL BE MUCH EASIER.

In the fall of 1994, Davis was climbing the Diamond, a multipitch wall on Longs Peak, when she looked over and saw a guy in black tights and a hot-pink windbreaker. “His hair was wild, and he was hyper and couldn’t find his next bolt,” she says. “I yelled over to him to tell him where it was, but all I could think was, ‘Who is this sport-climbing weenie?’”

Like Davis, Dean Potter was a young climber hoping to get better. He’d dropped out of the University of New Hampshire a couple of years earlier and was driving between crags, living in his VW Jetta. Potter tracked Davis down a few weeks after they met, but she wasn’t interested in a boyfriend. “I didn’t want to be distracted from climbing, so I put him off, until one day I finally relented,” she says. “It was fireworks and drama from then on.”

Davis and Potter began an on-again, off-again relationship, living together (in the back of one of

“Dean ran around Hueco Tanks with his friends,” Davis says. “I’d ask them to spot me on bouldering problems, but they would leave to go do harder stuff. So there I’d be, alone with my crash pad, hoping a stranger might walk by and help.”

They split up in the fall of 2001, just before they were scheduled to leave for Patagonia. Davis was hoping to finally summit Fitz Roy, an 11,073-foot glaciated peak in Argentina whose wicked storms had forced her off the mountain on a previous trip. She flew down alone and found a partner at the east-side base camp; as soon as the weather cleared, they summited. The next day, Potter soloed Fitz Roy from the west side, saw “girl crampon prints in the snow,” and knew Davis had made it. A month later, back in Moab, Potter proposed, and in June 2002 they got married in a meadow high in the La Sals.

From the start, nothing about their marriage was normal. They were rarely in the same place at the same time—and when they were, they fought over whose projects came first. Potter usually won, accepting Davis’s help but not offering much in return. “I had this perception that I had to be all virtuous and wifely and help him with his climbs and not have any of my own goals,” says Davis, who spent two months helping Potter train for his historic one-day free climb of both El Cap and Half Dome in September 2002. “But to be fair, he didn’t ask that of me. It was something that I’d made up in my mind.”

Davis and Potter began an on-again, off-again relationship, living together (in the back of one of their vehicles) and apart (in the backs of both of their vehicles).

After Potter completed the linkup, Davis assumed he’d return the favor by helping her on a difficult ascent of Cosmic Debris, a classic 5.13b crack climb in Yosemite. But he belayed her only twice during her successful effort.

“I was pretty tweaked after that,” she admits. “That’s when I started keeping score.”

Back in Utah, Potter wanted her to belay him on a 500-foot, three-pitch sandstone tower called the Tombstone, but Davis insisted that they climb it together, trading leads to put up the first—and, to date, only—free ascent in January 2003. Afterwards, when Davis wanted to try Pink Flamingo again—“it was festering, driving me down”—Potter took off for Yosemite, leaving her to fish around base camp for climbing partners. In March 2003, she put up the first female free climb of the route.

“I wasn’t mad at Dean,” Davis remembers. “He was psyched in Yosemite, and I made it work in Moab. I was climbing strong, and I realized this was how it was going to be: I had to be really self-driven. So I went back to the Valley and started working on other climbs, including Freerider.”

Snaking past buttresses and long cracks, Freerider rises 38 pitches to the summit of El Cap. Davis’s training program was part masochism, all discipline: Two or three times a week, she’d hike ten miles to the summit, self-belay a thousand feet down to the lower pitches, and climb up alone. “Most people don’t just walk up to El Cap and say, ‘Oh, I’m going to free it,’” she says. “It’s like playing piano: taking something big and breaking it down and then trying to achieve a perfect performance.”

Training solo is one thing, but free-climbing the entire wall without a partner was impossible. When Davis was ready to attempt the route, in April 2004, she needed a partner. At first Potter begged off, but then he changed his mind. With Dean belaying, she became the first woman to free the route, in four days. A month later, with the help of Austrian climber Heinz Zak, she returned to Freerider and became the second woman, after Lynn Hill, to free El Cap in a day.

As it turned out, Freerider was a turning point in her relationship with Dean: The couple finally accepted that their marriage, weird though it was, actually worked. “Our roles started to materialize,” says Davis. “We agreed that there are some things we’ll do together and some things we’ll do apart. The reality is, I wouldn’t really want someone following me around, bearing my rock shoes on a pillow and saying, ‘Rah-rah, Steph!’ That would get on my nerves!”

On an overcast Saturday in June, six weeks after I visited Davis in Moab, she and I were stuck in traffic in Yosemite Valley, sucking bus fumes on a one-way stretch of road between El Cap and Camp 4, the park’s infamous climber hangout.

“This friggin’ sucks,” Davis said.

I’d come to Yosemite to hang out with Davis at the apartment she and Potter rent in Yosemite West, a small pocket of private land just inside the park’s southwest boundary. She was just starting to train for the Salathé, and in the few days I’d been there, we hadn’t seen Dean very much. One night he cooked us dinner, but otherwise he was gone, meeting friends, dawn-patrolling on El Cap, and scouting for places to rig his highline—a glorified slackline strung a thousand feet off the ground.

We were on our own program anyway: hiking, bouldering, waking up at 5 a.m. to climb the , a slabby 5.6 route up Half Dome’s southwest face. When we weren't climbing, we were cruising, a very un-Davis-like activity that entails driving aimlessly around the

But there’s one small hitch. Since joining Patagonia, she’s had to reconcile her belief that climbing is a “pure path of spiritual joy” with the fact that it’s also a business.

Sometimes it happens the other way around. One day, while we were checking out the land Davis and Potter own—two steep, pine-needly parcels surrounded by oversize vacation homes—a guy in a two-door rental car pulled up beside us. A tiny woman with fluffy blond hair was folded up in the backseat next to a fussing child. It was Lynn Hill, her then-partner, Brad Lynch, and their two-year-old son, Owen, driving by for a visit.

Hill is still the most famous female climber in history; her one-day free ascent of the Nose—the classic 5.14 route up El Cap’s prominent center line—stood unmatched for 11 years, until 27-year-old Tommy Caldwell became the second person to do it, last October. Now she’s a sponsored Patagonia athlete who runs her own climbing camp and flies out from Boulder occasionally to see old Yosemite buddies.

“Owen got devoured by mosquitoes,” Hill explained, craning her neck forward to talk to us. It was starting to drizzle, but that didn’t stop Davis from launching into an animated monologue about organic bug repellent and her second-favorite topic after climbing: the weather. A few minutes later, Hill and Lynch waved and pulled away into the rain.

as a pro came in 1998, when Patagonia hired her as its first female “climbing ambassador” to promote its products in exchange for free gear, a paycheck, and the validation she craved. “When Patagonia said, ‘We admire your climbing achievements and we support you,’ it was like they were playing the role my parents never did,” said Davis. “Their support of my passion—even more than the financial support—means everything to me.” These days, she’s paid to travel the world doing what she loves—training and climbing, and occasionally pitching in to help Patagonia with product development and planning.

But there’s one small hitch. Since joining Patagonia, she’s had to reconcile her belief that climbing is a “pure path of spiritual joy” with the fact that it’s also a business. “To be a professional climber, you have to sell yourself and convince everybody you’re the best,” Davis says. “But I don’t think there is a ‘best.’ The minute you say you want to be better than someone else, you’ve immediately put a limit on yourself, and you’re a fool!”

Not everyone in the rock world buys her humility. Some grouse that she’s a self-promoter who doesn’t have the skills to back it up. “You can’t even mention her in the same sentence as Beth Rodden,” snipes one climber, who refuses to be named for fear of jeopardizing his own sponsorship.

Rodden herself doesn’t mind the comparison. “The women’s El Cap free-climbing scene is pretty small—just Steph and me,” she says. “And even then, Tommy and I have each other to belay through the hard pitches, but Steph does it alone.”

Others wave off the negativity as mere cattiness. “Pro climbers can be easy targets,” explains adventure photographer Jimmy Chin, who climbed Pakistan’s Tahir Tower with Davis in 2000. “Climbers will talk shit about them any day, but it’s possible to balance the exposure with the climbing, to keep your soul and work for a company.”

At least for now, Davis agrees. “Yes, I have negative feelings about marketing myself, but this is my job and my life, and I love it!” she says. “I don’t want to be the best; I just want to be better—that might mean being a better climber, having better style or a better attitude, or being better to the earth, to people, to creatures. And there’s no limit to that.”

As for the Salathé climb, it doesn’t get any easier. As the days wear on, Davis grows increasingly miserable. Her muscles are fried, she’s almost out of food, and the whole enterprise begins to seem ridiculous. Early on day nine, her belayer, Cybele Blood, hauls herself to the top on fixed lines to go for supplies, leaving Davis alone on her ledge.

All things considered, there are worse places to be: The day is sunny and still, and the entire Yosemite Valley spreads out below her. She can see riffly white rapids on the Merced River and, later in the afternoon, her own blue truck pulling out of the parking lot, heading west toward the grocery store.

If it weren’t for Blood, an itinerant climber from L.A. whom Davis met a couple of weeks ago, she wouldn’t be up here at all. She’d still be tacking up WANTED: BELAYER signs on the Camp 4 bulletin board and leaving half-pleading, half-cheerleading messages to get me to do it—even though I’d climbed a total of ten times in my life. Dean had agreed to help her on the Salathé's first 14 pitches, but she needed a partner for the rest.

By dawn on day 12, just 50 feet of nasty, overhanging granite stand between Davis and an easy 300-foot finish. She eats three aspirins. “I feel great,” she lies to Cybele, then starts climbing.

The sun rises onto the face, heating the rock and making her fingers sweaty. She falls. She thinks about failure. Then she hears a whoosh of bird wings, and suddenly all the doubt and struggle dissipate, and she knows what to do. Lunging through the final holds, feeling perfect at last, Steph Davis becomes the first woman to free the Salathé.

In the days that follow, she swings between elation and fatigue and her usual lingering insecurity. “I never once had that wonderful ‘Ahh, I'm a badass’ feeling,” she tells me. “Everything that could have gone wrong did. I should have gone down.” Mostly, though, she‘s relieved to be off El Cap. “I’m not doing a big Valley season anytime soon,” she says. “I’m just going to do what I feel like doing.”

Which means packing her truck, collecting her dog and husband, and going home to Moab. She needs to install a new woodstove and visit her parents, who are just back from a Hawaiian cruise. As it happens, there was a climbing wall on the ship, and one day Connie decided to try it. “They had these pretty little colored handholds, and I got two-thirds of the way up,” she tells me. “Then I looked down and thought, What’s this senior citizen doing way up here?”

A few months later, I call Davis in Moab. She’s about to leave for Patagonia and is already scheming her summer 2006 project: free climbing in the Italian Alps with Dean. Right off, I can tell something is different. The Salathé climb has finally sunk in; she seems almost relaxed.

“I don’t have to prove anything to myself anymore, or to anyone else,” she says. “For once, I have no expectations and no pressure. I just feel free.”