On the morning of May 4, I learned that the American Alpine Club (AAC) is planning to change the name of the Robert and Miriam Underhill Award, a prestigious annual prize that honors the memories of two outstanding alpinists, a husband-and-wife team who made a mark in the first half of the 20th century. For the past 39 years, the club has given the Underhill Award to an American climber who has “demonstrated the highest level of skill in the mountaineering arts and who, through the application of this skill, courage, and perseverance, has achieved outstanding success in the various fields of mountaineering endeavor.” The award’s 46 recipients include some of American climbing’s most famous names: Lynn Hill, Royal Robbins, Catherine M. Freer, Yvon Chouinard, Jeff Lowe, Alex Honnold, Conrad Anker, Jim Donini, Kitty Calhoun, and Peter Croft.

I never met the Underhills—he died in 1983, she in 1977—but I’d read about them, and I learned a few years ago that Robert, a revered figure in the history of California climbing, was an antisemite. In letters written to friends at the Sierra Club and the AAC in 1939 and 1946, respectively, he referred to Jews as “kikes,” “mutts,” and “lowgrade.” He implied that Jewish people didn’t belong on rock faces at all and said they lacked the character and physical traits to be successful in challenging mountain environments.

Robert Underhill’s distaste for Jews has been documented in two books by the climbing historian Maurice Isserman: , a sweeping 2010 history of Himalayan mountaineering, cowritten with Stewart Weaver, and , an epic 2017 account of climbing in the United States. Isserman’s books were well-known among climbers, but to my knowledge the AAC had never publicly addressed Underhill’s attitudes about Jews. Plenty of organizations have interrogated their problematic pasts in recent years. Shouldn’t the AAC?

I’ve been a club member for 21 years. I’m Jewish, and I’ve been the victim of antisemitism. Though I’d intended to write about Isserman’s research, I hadn’t gotten around to doing it. Then, on April 22 of this year, I scrolled through my email and found an AAC newsletter announcing the new winner of the Underhill Award—Joe Terravecchia—and I decided it was time to bring up Robert’s old statements. Later that day, I emailed the AAC. Citing Isserman’s research, I asked if they knew about the letters and whether they thought the organization should respond to their contents. Jamie Logan, the AAC’s interim CEO, emailed within the hour to thank me for reaching out. “As a recipient of the Underhill award my immediate reaction is that we should rename the award,” she wrote.

For 12 days, I didn’t hear anything else, and I wondered whether I was getting blown off. I also wondered whether I’d unwittingly blurred my role: Was I making the inquiry as a club member or as a journalist? I decided to write once more to ask if the silence was the same as no comment. But then, early on the morning of May 4, Logan emailed me. “Hi Brad, we have decided to rename the award. We are also doing some research into Miriam’s views before we finalize what to do.” On May 5, the AAC removed the Robert and Miriam Underhill Awardees page from its website.

In a subsequent email, AAC vice president Pete Ward offered more detail. “We view the AAC as the stewards of the most accurate possible history of climbing,” he wrote, adding that a process of renaming will involve creating a committee tasked with taking a deep look at the club’s past and future. “Our goal is to do this in a way that ensures we’re awarding meaningful contributions rather than simply being generic and performative. Whatever the new name is should at once honor the better parts of our history while also being precise in what we’re trying to celebrate with that award.”

Later that day, I talked to several Underhill recipients, who didn’t know about Robert’s antisemitism and were pleased with the AAC’s decision. “I had no idea he had that past,” said Lynn Hill, who won in 1984. “I believe that climbing is a sport that is inclusive and welcomes all races, all genders, and people who love climbing and love the earth and love nature and love humanity. And that is not humanity.”

“It’s flabbergasting,” said Peter Croft, who was honored in 1989. “This is black and white, not shades of gray. Changing the name is an awesome thing to do.”

“I mean, the whole point of naming awards is to basically put somebody on a pedestal,” said Alex Honnold, who won in 2018. “And if you find that they’re not worthy of the pedestal, then find somebody else.” Honnold even had an idea for a new name: “Call it the Peter Croft Award,” he said. “He’s the world’s nicest man. The Croft Award for Excellence in Climbing.”

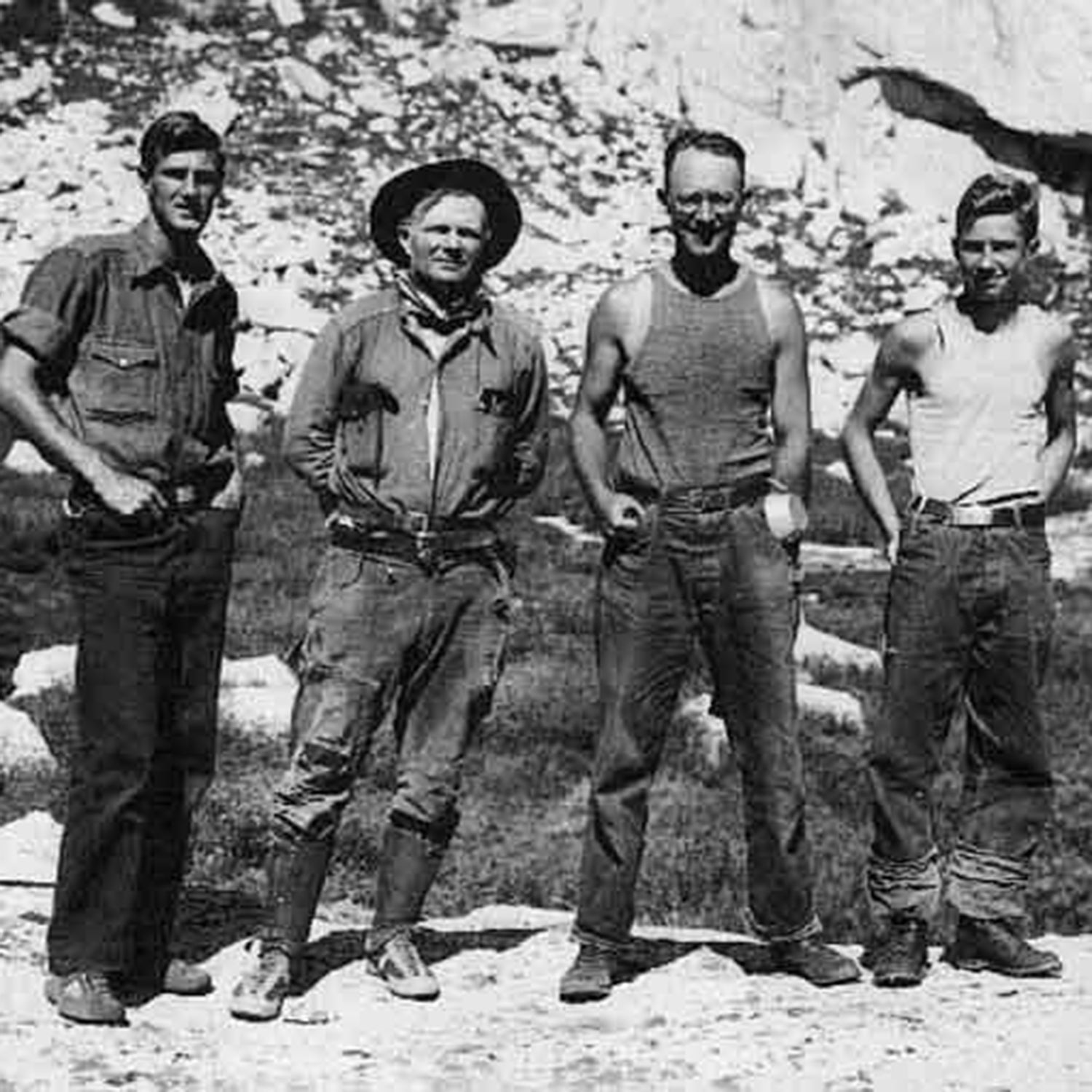

In the origin story of modern Yosemite climbing, few people loom as large as Robert L.H. Underhill, a professor of philosophy at Harvard who was the editor of the Appalachian Mountain Club’s journal and who, by the early 1930s, had put up notable ascents in the U.S. and Europe. In 1931, he traveled west to teach European rope techniques to a handful of the Sierra Club’s best climbers.

“Now it is necessary to understand that the rope, in its final meaning, is the symbol which transforms an individualistic into a higher social enterprise,” he wrote in an essay published in the Sierra Club Bulletin—an essay that followed the completion of a legendary Sierra climbing season. With Norman Clyde, Jules Eichorn, and Glen Dawson, Underhill made the first ascent of Mount Whitney’s east-face route that year.

“The time is summer 1931, the place [is] Garnet Lake in the Sierra Nevada,” writes historian Joseph E. Taylor III in , a 2010 history of Yosemite climbing. “Francis Farquhar has brought fellow Harvard man and celebrated mountaineer Robert Underhill to teach European techniques to the Sierra Club. Underhill treads the holy Range of Light like a mountaineering Moses, and the followers of John Muir listen reverently.”

In letters written to friends at the Sierra Club and the AAC in 1939 and 1946, respectively, Underhill referred to Jews as “kikes,” “mutts,” and “lowgrade.” He implied that Jewish people didn’t belong on rock faces at all.

Before she married Underhill in 1932, Miriam O’Brien had also established herself as a top-shelf climber and writer. Her essay “Manless Alpine Climbing,” published in the August 1934 issue of National Geographic, summarized her distinguished career as a pioneering alpinist—she was one of the best of her generation, of either gender. Together, Robert and Miriam, accompanied by two guides, had made the first traverse of the Alps’ Aiguilles du Diable in 1928.

Robert, an academic, a world traveler fluent in German, and a Quaker who was described by a classmate as “a quiet and unassuming person [who] never advertised his exploits,” was unusually expressive when it came to the subject of inborn human qualities. “Likening climbers to military comrades and ascribing leadership to the ‘virtue’ of ‘natural capacity’ and ‘inborn talent and natural instinct,’” Taylor writes, “Underhill echoed Victorian beliefs about the innate nature of masculine, physical superiority.”

Unfortunately, Robert also believed that the inborn qualities of Jews were lacking. In 1939, Sierra Club board member Dick Leonard wrote to him to ask about a climbing fatality that had happened near West Point, New York. The death occurred during an outing sponsored by the Appalachian Mountain Club, the country’s oldest outdoor-recreation nonprofit and Underhill’s organizational home. He replied by disparaging the fallen climber, who happened to be Jewish, and lamenting Jews’ membership in the New York chapter of the AMC. Isserman cites the letter in Continental Divide:

The A.M.C. has a New York Chapter, but the members are so afraid of getting stuck with kikes and others that they deliberately suppress any publicity it might have and make it almost impossible for new people to join! One can’t be sure some special Jewish psychology didn’t enter into this accident, at least fundamentally. It isn’t so usual for Jews to go in for mountaineering, and when they do I can conceive that they are conscious of invading what they may look upon as the other man’s sport, and consequently that they feel unduly impelled to make themselves felt by undertaking the spectacular.

When Isserman was researching Fallen Giants at the AAC archives in Golden, Colorado, he came across a letter dated June 24, 1946. Underhill was addressing Henry S. Hall, a former climbing partner and a fellow Harvard alum. He wrote:

Have you the pleasure of a personal acquaintance with Mr. James Ramsey Ullman? Neither have I but Miriam and I have just spent a night at the Lakes of the Clouds hut where he was present with his two boys. Unless I miss my guess, he is a lowgrade New York Jew—at any rate his boys are beautifully Jewish and he is incontestably lowgrade. . . . The New York chapter of the AMC would never let such a mutt through their censors; can the A.A.C. be less choosey?

The existence of Underhill’s antisemitic letters was no secret. In fact, Fallen Giants and Continental Divide merited coverage in the American Alpine Journal, the latter reviewed in 2017 by Peter Beal, who wrote: “Particularly interesting is a discussion of anti-Semitism and other forms of discrimination from very well-known figures in climbing, such as Robert Underhill.”

In the print edition of her 2007 memoir Breaking Trail, the mountaineer Arlene Blum mentions Underhill’s letter to Hall—without using either man’s name but making clear that it involved AAC business.

And yet, before now, the AAC’s board had not publicly discussed Underhill’s antisemitic predilections or considered the effect of his words on the organization. When I asked Pete Ward about the club’s institutional memory, he replied: “While I’m not willing to speculate on what has come before, I can say that the AAC staff and board are committed to a continual process of examining and shining light on all parts of our history. Including, and especially, the parts of that history that must evolve. We are accountable to our community and to ourselves to be open, accurate and transparent in that evolution.”

As for Miriam Underhill, Isserman told me he didn’t find any evidence that she shared her husband’s prejudices. Ward said that his team’s initial impressions are the same.

The dates of Robert Underhill’s letters are important. By 1939, Adolf Hitler’s persecution of German Jews was well underway. In July 1944, The New York Times reported that approximately 1.75 million Jews had perished at the hands of the Nazis, a figure that, tragically, turned out to be low. By 1945, Allied troops had started liberating a network of concentration and death camps. And in 1946, Underhill, presumably writing from the comfort of his New Hampshire home, saw fit to complain to his friend Henry Hall about the American Alpine Club’s Jewish problem.

I don’t wish to suggest that American Jews suffered from the same level of systemic othering, marginalization, and violence that some minority groups have in this country. At the same time, American Jews were barred from admission to certain clubs, subjected to quotas at institutions of higher learning, and redlined from neighborhoods. And yes, there were also victims of violence, including Leo Frank, who was infamously lynched in Atlanta in 1915.

When Underhill referred to Ullman as a mutt, he was invoking an age-old antisemitic trope, which had recently been employed by the Third Reich: Jews as a race apart, impure, an entire people requiring eradication. When Underhill complained to Leonard about the inclusion of Jews in the climbing ranks, he was reinforcing not only a classist system but also suggesting that by seeking admission to climbing clubs, Jews were overreaching.

Historically, a Jewish athlete’s successes served to puncture the negative cultural stereotypes that have portrayed Jews as weak, cowardly, and venal: images promulgated by the antisemitic propaganda of Nazi Germany and seen in the recent rise of both in the U.S. and abroad. “Sports [has provided] for distinctive ethnic identity and solidarity, [and] Jewish athletes during the inter-war years were viewed by fellow Jews as symbols of anti-racism resistance,” writes sociologist Richard Giulianotti in Sport: A Critical Sociology.

By limiting their membership to the ranks of the AAC, by demeaning a dead Jew who was supposedly killed by exceeding his abilities, Underhill was using his considerable influence to keep Jews down.

Simply put, a Jew—or a member of any marginalized people—who excels in an endeavor creates opportunities for those who follow. By limiting their membership to the ranks of the AAC, by demeaning a dead Jew who was supposedly killed by exceeding his abilities, Underhill was using his considerable influence to keep Jews down.

“There’s no way to interpret Underhill’s comments except as anti-Semitic,” Isserman told me in an email, adding that his tone reflected “his assumption that in revealing his own anti-Semitism he would not discredit himself in the eyes of those with whom he was corresponding.”

The award’s name needed changing, as did the narrative informing it.

who is a 75-year-old trans woman, knows something of courageous and transformative change. She won the Underhill Award in 2020 after transitioning in 2017. She took the lead on the decision to change the award’s name, and she’s facilitating a process to assess the sweep of the club’s history.

“It’s my feeling that any organization 100 years or more old should look into its past,” Jamie told me, “because it’s likely there will be problematic characters and incidents that don’t mesh with the present.”

Congratulations to Logan and Ward for starting organizational change. It’s a new board for a new time.