ON THE MORNING of October 24, 2010, veteran climbing Sherpa Chhewang Nima labored up from high camp on 23,389-foot Baruntse, a gabled summit near Everest in eastern Nepal. There were high clouds and strong gusts blowing fresh snow. At just over 7,000 meters and not particularly difficult, Baruntse doesn’t get classified among the world’s great expedition peaks, but it’s a popular stepping stone.

Roped to the 43-year-old was Nima Gyalzen, a Sherpa in his thirties from Rolwaling, a valley to the west. Normally employed by Seattle-based , Chhewang was freelancing on this trip, making $1,000. His only client was Melissa Arnot, a then 26-year-old professional climbing guide for who lives in Sun Valley, Idaho. (Arnot made headlines last May when she intervened in a now infamous brawl between Sherpas and three European climbers at Camp II on Everest.) Nima Gyalzen was working for an Iranian team. The two had paired up that day to break trail and fix the ropes that Arnot, the Iranians, and several other teams lower down on the mountain would use for protection on their summit bids.

Arnot was in high camp. She’d planned to follow along the next day, giving the Sherpas time to work. The snow was deep, but, said Arnot, “I saw that they moved quickly through the area we thought was going to be slow. I thought they may have gone all the way to the summit.”

At around 2 P.M., just 600 feet shy of the top, Chhewang was hammering in a picket with his ice tool when the ground split like a firewood round and gave way beneath him. He’d been standing on a cornice, a fragile dollop of wind-hardened snow curling out over the ridgeline into space. In less than the time it takes to register panic or resolve, Chhewang Nima was gone.

According to the account given by Nima Gyalzen, tumbling blocks of ice had sliced through the rope, ensuring Chhewang’s demise and likely saving Nima Gyalzen from being hauled over the edge as well. When Nima Gyalzen could find no sign of his partner, he frantically headed down. Arnot, who received him in high camp, initially mistook his hysteria for jubilation.

“I brought tea to him, and I said, ‘Nice work, you make it to summit?’ ” she recalled, using the simplified dialect of Everest that guides call Sherpa English.

“No, no, no—accident,” said Nima Gyalzen. “Chhewang Nima finished.” He collapsed into the snow.

Arnot called her in-country trekking agent, Jiban Ghimire, to request a helicopter for a body search.

AHEAD OF THE tragic 1996 Everest climbing season, the infamous subject of , ill-fated American guide Scott Fischer told writer Jon Krakauer, “We’ve built a yellow brick road to the summit.” He was referring to the miles of ropes that are now annually set along most of the South Col route between Base Camp and 29,035 feet. More accurately, however, it’s Sherpas who do the construction and, all too often, become its casualties. As a result of their work fixing lines, shuttling supplies, and escorting paid clients to the summit of Everest and dozens of other Himalayan peaks, Sherpas are exposed to the worst dangers on the mountain—rockfall, crevasses, frostbite, exhaustion, and, due to the blood-thickening effects of altitude, clots and strokes.

The spring of 2013 provided another devastating string of tragedies that illustrate how dangerous it is to work on Everest. On April 7, Mingma, 45, one of the legendary Icefall Doctors responsible for securing the route through the Khumbu Icefall for all of the teams on the mountain, fell into a crevasse near Camp II. On May 5, co-owner Eric Simonson wrote that his team had also “lost a member of our Sherpa family.” DaRita, 37, was at Camp III when he felt dizzy—likely “a sudden cardiac or cerebral event”—and soon died. Three days later, 22-year-old Lobsang, who was returning from Camp III for Seven Summit Treks, fell into a crevasse and perished. And on May 16, Namgyal, working for , succumbed to an apparent heart attack after summiting for the tenth time.

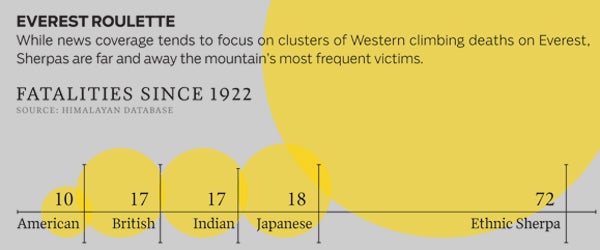

According to the , which keeps track of such things, 174 climbing Sherpas have died while working in the mountains in Nepal—15 in the past decade on Everest alone (see sidebar for a country-by-country comparison). During that time, at least as many Sherpas were disabled by rockfall, frostbite, and altitude-related illnesses like stroke and edema. A Sherpa working above Base Camp on Everest is nearly ten times more likely to die than a commercial fisherman—the profession the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention rates as the most dangerous nonmilitary job in the U.S.—and more than three and a half times as likely to perish than an infantryman during the first four years of the Iraq war. As a dice roll for someone paying to reach the summit, the dangers of climbing can perhaps be rationalized. But as a workplace safety statistic, 1.2 percent mortality is outrageous. There’s no other service industry in the world that so frequently kills and maims its workers for the benefit of paying clients.

The result is that in Kathmandu and in villages across the Khumbu region, dependents are left without breadwinners or, in the case of serious injury, forced to choose between supporting or abandoning a disabled husband. Take, for example, two climbing Sherpas struggling with post-stroke paralysis: Ang Temba, 54, and Lhakpa Gyalzen, 65. Ang Temba suffered his first stroke high on Everest’s north side while working for a Japanese team in 2006. His wife, Furba, 48, who cares for him at their home in Kathmandu, recalled the stern warning of the Japanese doctor who examined him in Base Camp following his rescue: “He said don’t go mountaineering.” But the next year, after making a relatively quick recovery, Ang Temba was offered a job working on Everest for Kathmandu-based . “There is no option other than mountaineering,” said Furba, illustrating the choice that so many Sherpas are faced with. “If he’d agreed with the Japanese doctor, then he would not be in this situation right now. It was a bad decision.”

Shortly after Ang Temba returned from the mountain in 2007, Furba found him unconscious on the couch. His right side is now paralyzed, and he can’t speak. “It’s more difficult than looking after the kids,” Furba said. “He goes to the toilet in a bedpan.” Still, Ang Temba is relatively lucky: Furba stayed with him and managed to collect roughly $5,500 when, after more than a year of wrangling, his employer’s insurer agreed that his disablement was complete, unrecoverable, and work related.

Lhakpa Gyalzen, who was climbing for a Chinese expedition in 2000 when he suffered a stroke, wasn’t so fortunate. Though he can still get around with a cane and has limited speech, his wife and kids have moved away. One evening last October, I went to visit him in Phortse, just 15 miles downhill from Everest. Lhakpa Gyalzen wasn’t home when I arrived, but when I returned the next morning he was in bed, eating a large plate of white rice that he’d cooked. The previous night, he explained, he’d fallen off the trail while limping down to the river—a 20-minute walk for a fit hiker—to cut bamboo for a religious ceremony. Unable to get up, he’d lain there for most of the night and then dragged himself home in the morning. “Very cold. Very hungry,” he said of his night out in the bushes.

Lhakpa Gyalzen was at 27,000 feet when he had his stroke. Immobilized, he slept there for two nights before the Chinese expedition sent some of the team’s Sherpas to retrieve him. When he got off the mountain, he had to pay for his own care. “The Chinese expedition didn’t pay any expense at the hospital,” he said. “All the expenses were done by my personal. Food, medicine, everything.”

CASES LIKE THESE unfold each year in relative obscurity. After a Sherpa dies on Everest, there are always heartfelt tributes from Western climbers. “The Sherpa[s] are the heroes of the Himalayas,” wrote a team from the U.S. Air Force earlier this spring after the death of Icefall Doctor Mingma. In most cases, there’s a government-mandated insurance payment of roughly $4,600, covered by policies taken out by the in-country trekking agents who arrange foreign outfitters’ on-the-ground logistics. And if the Sherpa was well known or worked for a top outfitter, there might be a hat passed around for donations, as was done last year after Sherpa Dawa Tenzing died of a stroke he suffered at Camp I. Professional climber Conrad Anker walked with HimEx owner Russell Brice to Phortse to deliver roughly $600 to Dawa Tenzing’s widow, Jangmu, who works as a farmer. (Brice, who has built a reputation for treating his Sherpa workforce well, said he “did much more” but would not elaborate for this story.)

Still, Western outfitters, guides, and their clients rarely witness the true fallout from a Sherpa death. In October 2010, when Chhewang Nima died, Melissa Arnot had to confront the realities firsthand. After searching for his body by air, Arnot and Nima Gyalzen helicoptered directly to Chhewang’s village of Thamo, landing in a potato patch behind the Tashi Delek, a small teahouse and guest lodge Chhewang had built with his earnings. By then, news had already reached the family.

“From outside I could hear the wailing,” recalls Arnot. “Like nothing I’d ever heard.” She entered the teahouse and found Chhewang’s widow, Lhamu Chhiki, and her boys, Ang Gyaltzen and Lhakpa Tenzing, then 14 and 12, in the kitchen. “I got on my knees in front of her and said I’m sorry. And a lama came and took me out of there and said, ‘You can’t be in here now, you have to go.’ ”

The scene Arnot was witnessing is one that has been repeated throughout the Himalayas since 1895, the year a British expedition first hired two locals to help them attempt Pakistan’s 26,660-foot Nanga Parbat. Both died on the mountain. Twenty-seven years later, during George Mallory’s 1922 assault on Everest, an avalanche tore through a rope team and killed seven Sherpas. In 1935, Everest pioneer Tenzing Norgay secured his first portering job in large part because six of the most experienced Sherpas had died the previous year on Nanga Parbat. In those early years of exploration, casualties were accepted as an unfortunate price of conquest. The question is whether, in 2013, the summit of Everest is still worth this kind of banal and predictable human sacrifice.

In the past decade, Everest has been transformed into a tourist attraction, the cornerstone of Nepal’s $370-million-a-year adventure-travel industry. Thanks to explosive growth in commercial guiding, the more than 300 paid clients who arrive each spring to attempt the Southeast Ridge route can mitigate their own risk by having Sherpas do the most dangerous labor for them. But little has changed for the workforce. The families of the men killed on the Mallory expedition in 1922 were eventually given 250 rupees each, a payout that, adjusted for inflation, is in line with the standard $4,600 insurance claims Sherpas receive today.

As Arnot would learn, that money doesn’t go very far. By the time she’d arrived in Thamo, several lamas had already come down from the monastery above the village to begin preparing for the puja, an elaborate Buddhist ceremony meant to speed the deceased’s spirit toward reincarnation. These ceremonies, which can cost more than the life-insurance payment, often end up compounding a widow’s grief with debt. Soon after, Arnot was confronted by members of Chhewang’s family who wanted to immediately launch an expensive body-recovery expedition. The urgency was over Chhewang’s spirit, which was at risk of getting lost and wandering the earth if it wasn’t set free within seven days by cremation. “I begged them not to go,” said Arnot, worried that others might die trying to recover the body. They went anyway and never made it beyond Base Camp due to snow conditions. Arnot paid $19,700 herself in helicopter fees and says her sponsor Eddie Bauer wired $7,000 to cover the puja. Arnot has now committed to paying Chhewang’s family what she can—which has amounted to roughly $4,000 a year—for as long as she’s guiding, though it hasn’t entirely eased her conscience.

“It’s the guilt of hiring somebody to work for me who really had no choice,” Arnot told me last October in Nepal, where I’d joined her on her second annual trek to visit Chhewang’s widow. “My passion created an industry that fosters people dying. It supports humans as disposable, as usable, and that is the hardest thing to come to terms with.”

THE SHERPA VILLAGE of Thame rides a high bluff of green pasture that’s gradually eroding off a 500-foot earthen cliff into the Bhote Kosi river. A 45-minute walk downstream is Thamo, home to another 40 or 50 families. Together they occupy the first arable land downvalley from Nangpa La, the 19,000-foot pass near Cho Oyu that the Sherpas have used for the past 500 years to cross into Nepal from Tibet.

These two towns have also been home to some of mountaineering history’s most famous Sherpas. Tenzing Norgay lived in Thame before he moved, in 1932, to Darjeeling, India, where expeditions were organized before Nepal’s monarchy opened the country to Westerners. Thamo’s Ang Rita, now 65, climbed Everest ten times without bottled oxygen, a record that earned him the moniker the Snow Leopard. And Thame’s Apa, the Super Sherpa, now 53, made his record 21st Everest ascent in 2011.

With his natural athleticism, Thamo’s Chhewang Nima becoming a climber was as inevitable as a broad-shouldered West Texan playing football. Like all young men coming of age in the village in the 1980s, superheroes like Ang Rita and Apa were his role models. At the time, Everest expeditions were still undertaken only by elite national teams, but supporting them was already the most profitable industry in the Khumbu. Climbers recognized the Sherpas’ superior strength at high altitudes, a genetic gift confirmed in studies that show Sherpas can process oxygen more efficiently. The Sherpas, then as now, recognized both the risk and the opportunity. In a 1981 essay in CoEvolution Quarterly by Thomas Laird, who frequently writes about Tibet, a Sherpa named Dorjee explained it like this: “A pilot they make much money but if accident, dead. If not accident, they are rich. We are the same with expeditions.”

Chhewang began his career in 1993, at age 25, at Alpine Ascents, apprenticing under his cousin Lakpa Rita. Within three years, the Nepalese government granted an unlimited number of permits for the popular Southeast Ridge route, a move that gave rise to the commercial era and expanded the number of opportunities for young men with dreams of making a name for themselves in the mountains. The careers of Chhewang and Lakpa Rita trace Everest’s arc from a capstone summit for elite climbers to a $30,000 to $120,000 package tour that anyone with a credit card can book online, a transformation that turned Thame and Thamo into virtual company towns where most of the climbers are employed by Alpine Ascents. The relationship has been profitable on both sides. Lakpa Rita has become one of Everest’s most well-respected sirdars (the boss of an outfitter’s Sherpa workforce) and now, as a recently naturalized U.S. citizen, splits his time between Seattle and Nepal. Chhewang rose steadily through the ranks as well, emerging as one of the industry’s most dependable climbers.

At the time of his death, Chhewang had climbed Everest 19 times and was on track to break the aging Apa’s summit record within two years. As a top climbing Sherpa, however, Chhewang earned $6,000 per two-month climbing season to fix ropes, stock camps, and shuttle clients’ gear, food, tents, and oxy-gen up and down the mountain—while top Western guides, carrying less but charged with clients’ safety, can make up to $50,000 including tips. With his salary, Chhewang was supporting not only his own wife and children but the families of many of his eight brothers and sisters as well.

“If somebody in America climbs Everest 19 times, he’d be all over Budweiser commercials,” said Norbu Tenzing Norgay, 50, Chhewang’s cousin and the eldest living son of Everest pioneer Tenzing Norgay. “Sherpas don’t get the same recognition.” In the summer of 2010, while Chhewang was working in Alaska training trekking yaks for Alpine Ascents, Norbu, who now lives in San Francisco and is a vice president of the American Himalayan Foundation, was trying to help him land a serious sponsorship. He had coached Chhewang on how to artfully field questions from reporters, and in July he asked a publicist to shop Chhewang’s résumé around to several of the top brands. They included , which had sponsored the late Babu Chiri, the legendary Sherpa who held the speed record on Everest but died in 2001 after falling into a crevasse near Camp II. Norbu talked to Chhewang, who he recalls was making “a pittance” compared with Western guides, about postponing his trip home from Alaska to Nepal so he could meet with potential sponsors in San Francisco. “He said, ‘Oh no, brother, it’s too expensive to change the ticket.’ I didn’t realize it was just a couple hundred bucks.”

A few weeks later, Norbu was traveling for business in India and channel surfing when he saw the news about his cousin. “I’m sitting in a hotel room in Ganges, and there’s a BBC story that he’d died,” he recalls. “I was completely shocked.”

The tragedy has left him questioning the fairness of a profession that so many of his family members continue to depend on. “I’ve lost a number of relatives on Everest and other mountains just carrying other people’s crap,” he told me. “Times have changed. It’s not the fifties anymore. It’s the Everest business. Sherpas are being pushed to climb Everest because people paid sixty grand.” While he appreciates the attempts Arnot and other Western climbers have made to help, he doesn’t believe goodwill alone can rebuild the families destroyed by climbing. “Intention to help is not good enough. I’ve seen so many broken promises.”

THERE HAVE BEEN improvements for Sherpas working on Everest in the past decade. In the early days of expedition climbing, Sherpas received very little training and relied almost solely on their unique ability to operate at high altitude. Today, many of the 10,695 Sherpas registered as sirdars and support climbers take courses offered by the in Langtang or by the , a nonprofit training school for high-altitude porters in Phortse. The latter, where Chhewang was a regular instructor, was founded by American professional climbers Conrad Anker and Peter Athans in 2003 and built by a group of Montana State University architects. At both schools, Sherpas learn rope and high-angle-rescue skills. Another Montanan, Luanne Freer, launched her Everest ER clinic in Base Camp in 2003 and offers free care to all Sherpas whose expeditions have contracted with her organization.

In addition, there is now a small, mandatory safety net in place to aid injured Sherpas or support their families in the event of a death. Since passage of the 2002 Tourism Act Amendment, Nepal’s Ministry of Tourism and Aviation has required all local trekking agents to purchase rescue and life insurance for their porters. Sherpas working above Base Camp need at least $4,600 in death coverage and $575 in medical, while low-altitude porters must be insured at $3,500. Each expedition must also cover its Sherpas with, collectively, at least $4,000 in rescue insurance.

Still, it doesn’t take long to discover how inadequate most of these measures really are. While training is significant, no amount of practice inoculates Sherpas from the increased exposure to risk they’re asked to take on in the mountains. Walking through the Khumbu Icefall, a shifting glacier with the constant threat of calving, is considered so dangerous that some outfitters acclimatize their clients on neighboring peaks to avoid traveling through it. In a typical season, a climbing Sherpa might make a dozen round-trips through this area, some earning a bonus for each extra lap. Guides and clients usually make between two and four.

When it comes to rescue insurance, the $4,000 coverage is almost meaningless. High-altitude helicopter rescues, which became routine starting in 2011, have drastically increased the chances of surviving an accident above Camp II. They also cost $15,000 each—more than three times what the required insurance will cover. That gap has already led to embarrassing problems.

In 2012, Sherpa Lakpa Nuru was beaned by a falling rock on the Lhotse Face and lay bleeding and semiconscious at Camp II. Meanwhile his expedition leader, Arnold Coster, haggled with Summit Climb’s in-country trekking agent, , over a medevac’s $15,000 price tag. About a half-hour into the negotiation, Rainier Mountaineering guide Dave Hahn came over the radio from Camp II urging other expeditions in Base Camp to take up a collection before the rescue became a body recovery.

“The trekking agent might have been hesitant to commit to such a large expense,” acknowledges Summit Climb’s owner Dan Mazur, who confirmed that he eventually paid $11,000 out of pocket for the uninsured portion of the flight. Lakpa Nuru survived, and last October, when I stopped by his home in Phakding, he was already back out working in the mountains despite recurring headaches and problems with his balance.

The $4,600 death benefit is similarly deficient. While that money represents a large sum in a country where the average annual income is still $540, it’s rarely enough to provide for the extended families many climbing Sherpas support. Western climbers will often swoop in to help fill the gaps, but this leads to an unfortunate disparity between outcomes. The family of Chhewang Nima are fortunate that he was so popular. In addition to Arnot committing to replace Chhewang’s annual salary and Eddie Bauer contributing $7,000, the Khumbu Climbing Center’s Athans and Anker raised another $5,000 for their star instructor. “Chhewang was very well liked,” explains Athans. “Conrad just happened to be at a sales meeting for the North Face and passed around a hat.”

Acknowledging the downside of such chance generosity, Athans continued: “Obviously, we realize that someone like Chhewang’s wife is doing better than most of the other folks who have lost a significant family member. There are other people who become destitute. It’s one of those things that tourism has neglected.”

NEARLY EVERY VETERAN guide and outfitter I spoke with was aware of the inadequate safety net, and many of them were actively trying to make a difference. Anker and Athans are working on a fund they hope to use for Sherpa insurance premiums. Alpine Ascents owner Todd Burleson established the Sherpa Education Fund in 1999 to help Sherpa children go to boarding school in Kathmandu. (My translator for this story, Tsering Tenzing, an impressive young man from Thamo, is finishing his bachelor’s degree next year with help from the fund.) Arnot and former Alpine Ascents head guide David Morton recently set up a nonprofit called the , which they’ll use to disburse aid to Sherpa widows, lobby the government for stiffer requirements, and urge outfitters to adopt a set of best practices. There are many other such programs, run by outfitters and climbers alike.

Despite these good intentions, there remains a surprising lack of understanding among clients and outfitters about how Sherpas are covered. Many outfitters I spoke with were aware of the insurance requirements but had no idea how much they paid out. For example, when I spoke with Peter Whittaker, the owner of , a boutique outfitter known for running small, high-end trips, he said, “I trust my Nepalese outfitter is meeting the requirements, but I’ll have to confirm specific insurance details.” When he subsequently checked with his in-country agent, High Altitude Dreams, Whittaker—whose company has an enviable safety record—discovered that his Sherpa staff had been covered at an above-average $8,000 until 2012 but this year dropped back to the minimum.

In fairness, the current system for employing Sherpas promotes a certain amount of this ignorance. Guided clients typically hire Western outfitters like Rainier Mountaineering, which in turn are required by law to hire in-country trekking agencies. It’s those trekking agents who actually hire the Sherpas, purchase insurance for them, and help them collect after an accident. On the one hand, the trekking agents act as docents, helping outfitters navigate Nepal’s disorganized bureaucracy. But they also make handy scapegoats after a snafu, since they’re the Sherpas’ technical employer. The system fosters a kind of plausible deniability in which each person thinks he’s acting in good faith while others are failing. A Brit named Mark Horrell, who was on Baruntse days after Chhewang’s death in 2010, illustrated this common fallacy in a 2011 e-book titled . After the body-recovery mission had been abandoned, Horrell’s partner speculated that Arnot was “a single climber, rich, American, offering a lot of money to fix ropes up there.” Meanwhile, Horrell noted, “All of our porters are insured by our agency the Responsible Travellers.” In fact, they all had the same anemic policy.

In Nepal, “the minimum is the standard,” explained Dip Prakash Panday, the CEO of Kathmandu-based Shikhar Insurance, which covers many of the expeditions going to Everest. If the life insurance requirement is only $4,600, there’s no incentive for the trekking agencies who hire Sherpas to go higher than that. Some of these agencies recognize the issue and are willing to change their practices, but they fear that increasing their premiums will mean losing business. “I’d go to $11,000,” said trekking agent Jiban Ghimire at a meeting last fall in Shikhar’s board room. “But I don’t want to be the only one.” Ghimire’s company, , is among the most prolific in-country trekking agencies, providing logistics for big-name clients such as Alpine Ascents, Eddie Bauer, the North Face, and National Geographic, among others.

On June 4, following the deaths of four more Sherpas on Everest, the Nepalese government announced increases to the mandatory insurance minimums, which will go into effect in 2014. Rescue-insurance requirements have jumped from $4,000 to $10,000, an incremental improvement, but still less than the cost of a helicopter flight above Base Camp. Health coverage will rise from $575 to nearly $4,000, a significant change for the better. Death and accident insurance, however, which will rise from $4,600 to $11,000 for high-altitude workers, is still inadequate. Several of Nepal’s insurance companies are willing to cover workers with the most dangerous jobs for up to $23,000, a move that, for large companies like International Mountain Guides and Alpine Ascents, which use approximately 20 Sherpas above Base Camp, would cost less than $2,000 more per season.

ONE THING THAT nobody is proposing to do away with is Sherpa support in the Himalayas. Without their efforts, no commercial expedition would make it to the summit. And as demonstrated by the number of Sherpas who get seriously injured only to return the very next season, the work is still in high demand. “If you could cancel all the work going to Everest,” said Athans, “unanimously, they’d say no.”

In Edmund Hillary’s time, the Sherpa-supported siege style that’s still favored by commercial expeditions was the only way. But as the light-and-fast tenets of alpinism have taken hold, using Sherpas above Base Camp has fallen out of favor just as much as using supplemental oxygen, at least among the elite professional climbers who come to Everest each year looking to put up historically significant new routes. This spring, the now infamous Everest brawl underscored the growing rift between elite climbers and the Sherpas who depend on Everest employment.

The conflict centered on two top professional climbers, Italian Simone Moro, 45, and Swiss Ueli Steck, 36, and their British photographer, Jonathan Griffith, 29. The three ignored the custom of staying off the Lhotse face while a Sherpa fixing team was installing the ropes. Each team accused the other of knocking ice down on its members. They argued, each deprived of oxygen at 23,000 feet and speaking in their second or third language, English. Tempers flared. According to 28-year-old Karma Sarki, one of the Sherpas on the Lhotse Face that day, Moro called them chor (“thieves”). Moro also admits to shouting machickne (Nepali for “motherfucker”), which was captured by a Sherpa’s hot radio microphone and broadcast around the mountain.

The actual fight took place when the two teams returned to Camp II. Moro and Steck were kicked, punched, and hit with rocks. Though bloodied, they didn’t require medical treatment. Melissa Arnot, who was going for her fifth summit, the most by any non-Sherpa woman, got in between the Europeans and the Sherpas to try to break it up. “I felt it was much less likely that they would hit me with a rock or anything else, just being a woman,” she told Good Morning America via satellite phone from the mountain.

In the days after the event, Moro, Steck, and a host of top pros would reiterate their belief that they had a right to be on the Lhotse Face and that they didn’t need Sherpa help. “We pay a lot of money to be there, so why should I not be allowed to climb?” Steck told �����ԹϺ��� Online. Still, the very idea of an unsupported climb on the south side of Everest is a fallacy. Steck and Moro may have been climbing unsupported, but just getting to Camp II required using Sherpa-installed ladders through the Icefall. During a celebration at the British Embassy in Kathmandu last May to commemorate the 60th anniversary of the first Everest summit, Reinhold Messner, considered the dean of modern alpinism, had harsh words for mountaineers who want it both ways. “Climbers who cross ladders set by Sherpas at the Khumbu Icefall,” he told the crowd, “then go up without ropes and claim to be special are parasites.”

Karma Sarki, who was also involved in the fight that day, said that Moro had insulted their work in addition to calling them offensive names. “He said, ‘Do you need money? We will fix the ropes up to the South Col.’ ” And by climbing Alpine style, the Europeans had moved much faster than the Sherpas that day, causing the rope-fixing team to lose face. “The Sherpas were furious because the three climbers had overtaken us,” Karma Sarki continued, “and they did so in our country, on our mountain. We put our lives at risk for climbing Everest and helping the foreign climbers. Everest is everything for us.” None of these factors excuse the Sherpas’ violent actions, but the apparent double standard—using Sherpa help, but only some of the time—might explain why the rope fixers were so angry.

This blurring of lines is beginning to occur throughout the sport. Top climbers continue to put Sherpas in harm’s way despite the wide-spread belief that pros should do their own dirty work. Arnot was fully capable of leading on Baruntse in 2010 but chose not to. More recently, in July 2012, Lhakpa Rangdu, a soft-spoken, 44-year-old father of three and ten-time Everest summiter, was hired by a Scottish and South African trio to attempt the unclimbed, six-mile Mazeno ridge on Pakistan’s 26,657-foot Nanga Parbat, “one of the most coveted goals left in the Himalaya,” according to the team’s website. Along with one of the team’s other two Sherpas, Lhakpa Zarok, he broke trail to roughly 650 feet from the summit before turning back.

“We were hired for fixing the lines,” Lhakpa Rangdu said last October in the small ground-floor apartment he and his wife, Lhakpa Diki, 36, rent in Kathmandu’s Dhapasi neighborhood. He sat with his left foot crossed over his knee, revealing a knotted and scarred ankle. When he fell—catching a crampon in the rocks and breaking his ankle—Lhakpa Rangdu was roped to South African Cathy O’Dowd, then 43. The pair, along with the team’s other two Sherpas, were descending while Scots Sandy Allan and Rick Allen went for the summit. “Fortunately, we were one day away from the valley,” said O’Dowd. “He had to climb down the next day on a broken ankle.”

Ten days later, after a horse ride into town and a flight back to Kathmandu, where his foot was X-rayed, Lhakpa Rangdu was told by a doctor at the Om Hospital that he’d need surgery. He had $575 in medical coverage and paid an additional $500 out of the $3,000 he earned from the expedition. Pakistan also requires insurance for Sherpas, but here again, the details weren’t something the climbers, who are understandably more focused on staying safe and making the summit, had spent a lot of time thinking about. “Most of that was done by our ground agent, �����ԹϺ��� Pakistan, so I can’t tell you how it works,” said O’Dowd. “But the Sherpas definitely had insurance.”

Sandy Allan, who calls Rangdu an “ace man and a very dear friend,” wired him another couple of thousand. “We did not give money just because he broke his leg, though,” wrote Allan in an e-mail. “I knew he would get it fixed by the insurers.” Instead, Allan wanted to help Rangdu feed his family while he was out of work.

Allan and Allen’s July 16 summit via the Mazeno ridge was a historic mountaineering first. It was also achieved using hired Sherpa support, a fact that would usually be in direct conflict with the strict standards of modern alpinism. But in April 2013, at a ceremony in Chamonix, the two won a coveted Piolet d’Or (golden ice ax), the highest award in climbing. O’Dowd tweeted, “A Piolet for Mazeno ridge, as much for Lhakpa Rangdu, Zarok, and Nuru, as for those of us at the event.”

“All of clients are very happy with the Sherpas,” Lhakpa Rangdu told me back in October. “The Sherpas are not for summit; we are for work.”

LAST OCTOBER, I crowded into a small mud-wall apartment in Namche Bazaar, where Lakpa Rita’s niece (and Chhewang’s cousin) Nima Lhamu steamed momos on an electric hot plate to sell to porters hauling goods to the weekly market that gives the town its name. Former Alpine Ascents guide David Morton, his wife, Japanese-American Kristine Kitayama, an administrator at Alpine Ascents, and their two-year-old son, Thorne, were there, too.

In April 2006, Nima Lhamu was six months pregnant with her and husband Dawa Temba’s first child when he died in the Icefall along with two other Sherpas. He was 22. “I was pregnant, and when I tried to go to Kathmandu, the insurance money was already taken by his mother,” said Nima Lhamu. “After that they started fighting with me and then stopped talking to me.” Her son Tenzing Chosang was born a few months later. Two years ago, Nima Lhamu remarried Karma Sarki, the Alpine Ascents fixer. Following Sherpa cultural mores, in order to take another husband, she left then four-year-old Chosang in the care of her parents, Dati and Pasang Rita, a retired Everest climbing Sherpa. Morton and Kitayama have volunteered to sponsor Chosang’s schooling. It was a blur of overlapping relationships that seemed to capture the whole complicated mess. For more than a hundred years, Western climbers have helped raise Sherpas out of poverty to ethnic celebrity, inadvertently smashing families and then struggling to help piece them back together.

The following day, I accompanied Arnot on a walk to Thamo to visit Chhewang Nima’s widow, Lhamu Chhiki. Chhewang’s surviving children, Ang Gyaltzen and Lhakpa Ten-zing, were home on school break to visit their mother. Her house, the Tashi Delek lodge, sits behind a low wall just downhill from a long row of carved Buddhist mani stones that divide the trail.

Lhamu Chhiki met us in her kitchen, wearing a traditional striped Sherpa apron and looking grave. She teared up as soon as she saw Arnot but motioned for us to sit and served tea. Arnot told her that she may have found work for her at the Sherpa �����ԹϺ��� Gear store in Kathmandu. Then she handed her an envelope stuffed with U.S. hundreds, a ritual Arnot told me is the hardest thing she does each year.

After 15 minutes of catching up, I asked Lhamu Chhiki if it would be OK for Arnot to leave and for me to interview her alone.

“I never wanted my kids to be mountaineers,” Lhamu Chhiki said. “I want to give them an education so after they are raised they can do something other than mountaineering.”

Toward the end of our brief exchange, I asked her whether she blamed Arnot for her husband’s death. “No,” she said, “I don’t blame Melissa.”

Up the trail in Thame that night we met up again with the Mortons, who’d agreed to walk Nima Lhamu’s son Chosang back up to his grandparents’ house in Marlung. The next morning, out on the village’s east-facing terraces, the air was so still that the only sounds were the bells on the dzos and the tiny stream running past the Sun Shine Lodge.

�����ԹϺ���, we met Nima Lhamu’s brother, Mingma Tshering, a handsome 21-year-old with high, broad cheekbones who speaks good English. He’d recently finished high school in Kathmandu, thanks to the sponsorship of a German benefactor, and he told us he sees options for his future. “The people in the old times weren’t educated,” he said. “They were forced to go to Everest.”

Then again, he also grew up hearing his father, Pasang Rita, cousin Chhewang, and uncle Lakpa Rita tell the same stories of Everest we’ve all read over the years. “From my childhood, I’ve dreamed of climbing Everest,” he said. Pasang Rita retired from working the expedition peaks in 2012. “Me and my younger brother are planning to go instead of him,” said Mingma. He’d decided to work on Everest but hadn’t told his sister Nima Lhamu his plans. “I want to experience the mountain life. Maybe it will be only one time that I climb Everest. After that, no risky job.”

He’s been told that once you start, it can be hard to quit.

Senior editor wrote about the 1963 American summit of Everest in May. Additional reporting by Deepak Adhikari. to the complete story, read by the author.