Cyclist Danny Chew completed his first 200-mile day when he was 10 years old. It was 1972. He rode an orange Schwinn Stingray with high-rise handlebars and a banana seat. He rode for 23 and a half hours through the rolling hills near Lodi, Ohio, through daylight and darkness, then limped into his family’s shag-lined Ford van, a small kid in cutoffs and sneakers. His back was sore but his heart singing. “I felt satisfied,” he says modestly. “I knew that I’d done something pretty cool.”

For many people, the thrill might have been a passing thing, an evanescent boyhood delight. But Chew has Asperger’s Syndrome, and even though he is now 54, his giddy, kid-like fervor has never waned. It has instead distilled into a bright, lifelong monomania. He is arguably the most focused cyclist in the world. When Chew was 21, he resolved that he would ride a million miles before he died. He started logging his rides, obsessively, in hardbound notebooks. He kept records on how many thousand-mile weeks he rode, on his centuries and double centuries, as well as his streaks of 100-mile days. Graphs captured his yearly mileage and number crunching revealed that between 1978 and 1982 he rode an average of 14,867.0 miles a year. Neatly penned notes recorded strange adventures—like the time he rode the long way from Pittsburgh to Cleveland, 182 miles, without drinking water or eating. He decided that he would never pursue a career, and that dating was not his cup of tea either. “It’d be nice to have a relationship,” he thought, “but then I’d have to get a job. She’d want kids. My riding time would go down, and I’d end up resenting it.”

Chew lived with his mom. He remained a virgin until he was 38. He became the world’s greatest cheapskate, subsisting on little more than stale bread and expired jars of mustard, and he rode, fast. Chew completed the Race Across America eight times and won it twice, in 1996 and 1999.

What Chew is most famous for, however, is an annual post-Thanksgiving bike ride that he helped launch on a snowy day in Pittsburgh in 1983 and has coordinated solo since 1986. The Dirty Dozen climbs 13 of greater Pittsburgh’s steepest hills, with riders racing the ups and coasting the downs. Eleven-time winner Steve Cummings calls it a quintessentially “Chewish” event. “He picks the worst weekend to do it,” Cummings explains, fondly. “The weather is horrible, and he never gets any permits—he just shows up and starts it.”

Cycling Toward Recovery

This year’s Dirty Dozen will raise money for Chew, the event’s longtime coordinator and guiding spirit.

This year’s Dirty Dozen will raise money for Chew, the event’s longtime coordinator and guiding spirit.The 34th Dirty Dozen, set for Saturday, November 26, will draw about 300 riders and will also, tragically, be a fundraiser for Chew. On September 5, he suffered a life-changing accident. While out for a ride in the green countryside in eastern Ohio, where he was visiting friends, he crested a gentle hill and then began descending at a ho-hum 20 or 22 miles per hour. It was a placid day—sunny, with no wind. He and his training partner, Cassie Schumacher, were chatting when suddenly Chew felt dizzy. “He veered left,” Schumacher says, “into a ditch, a typical drainage ditch with high grass, and I never heard any screaming. He never lost consciousness, but he hit his head and he just lay there, face down, saying, ‘I feel freaky. I can’t feel my legs. Am I still part of the bike?’”

He was 783,000 miles into his million-mile quest.

It’s early October now, and Chew is lying in his bed at the Rehabilitation Institute of Chicago, reckoning with the cold reality that he is now paralyzed from the waist down, with drastically decreased abdominal function and also a reduced ability to curl his fingers and grip. The accident broke his neck and irreparably bruised some of the roughly one trillion nerves in his spinal cord—nerves that simply don't regenerate with the vigor of other tissues.

“It’s a good thing I don’t have a loaded gun or Dr. Kevorkian with me,” he says, his voice nasally and flat as I arrive for a three-day visit. “It’s a lot to take—to give up that sense of freedom that comes with riding a bike.”

Typically a dry-eyed stoic, Chew is now weeping whenever the Dirty Dozen comes up. “A lot of people have children,” he says, “but the Dirty Dozen is my kid, and it’s all grown up now, and I’m so proud. I’ve had people come up to me after the ride and say, ‘Thanks for the greatest day of my life.’ I give these people a goal—to finish every hill.”

Still fresh from the accident, Chew is now almost wholly dependent on the rehab staff: moving him from the bed requires two caretakers, who wriggle him into a sling attached to a small crane that hoists him up before lowering him down into his wheelchair. Still, he has a new goal: he wants to complete his million-mile quest on a hand cycle. “If I could ride 200 miles a week, 10,000 miles a year,” he says, “I could do it.”

His physician, Elliott Roth, the chair of Physical Medicine and Rehab at RIC, has warmly embraced Chew’s mission, saying, “I don’t think it’s impossible at all. Danny’s got a lot of things working against him, but 50 percent of people’s outcome is related to their own determination.” Meanwhile, there are so many competitive hand cyclists with Chew’s level of disability (technically speaking, he is afflicted with T1 quadriplegia) that an entire division, Class H2, is reserved for them in international Paralympic races. The H2 world champion—42-year-old former Team USA wheelchair rugby player Will Groulx—rides 180 or so miles a week.

On this crisp fall morning in Chicago, however, Chew doesn’t even own a hand cycle yet. He is moving through the hallways in a large, clunky, high-backed wheelchair designed to be pushed from behind, and when his physical therapist steps into the room, asking him to self-propel that chair for six minutes, he is jittery, terrified. “Six minutes?” he says. “I’m going to be exhausted.”

Chew’s neck is still broken and braced. The shoulder muscles surrounding his broken neck are taut. His hands cannot grip very well and—worst—his newly paralyzed body is not effectively regulating his blood pressure. “Before,” Roth says, “the muscles in his legs pumped blood up into his heart. Now that’s not happening, and his body is adjusting to the change.”

Chew begins pushing the wheelchair down the corridor, and it’s a bit agonizing to watch. He is a world-class athlete; now he is moving with the weary doggedness of a 90-year-old in a nursing home. He is gritting his teeth and grimacing, and the wheels of his chair are not quite rolling, but rather eking forward in tiny, spasmodic lurches. The discrepancy between past and present is so profound, and so humbling, that it almost seems like giving up would be the most graceful course. But Danny Chew is used to racing through the night on three hours’ sleep. He’s crossed the plains of Arkansas at 2 a.m., riding into the wind with his neck aching and spittle on his face, and now he knows that only by resorting to his greatest strength—his focus—can he lift himself out of despair. He keeps pushing the wheelchair. Then, one minute and 50 seconds into the session, he stops. He is ashen and afraid that he will pass out. When the PT takes his blood pressure, it is 81 over 52. Later, after she bends to the floor with a tape measure, she announces that he has covered 46.9 feet.

“I’m really tired,” he says. “I’m so tired right now that I could fall asleep.” The PT rolls him back to his room. He’s airlifted back into bed, and I stand over him as he nods off. His body is long and lean under the sheets—devoid of body fat, ripped. And now his legs do not operate. Listening to the rise and fall of his breath, I feel nothing but mournful.

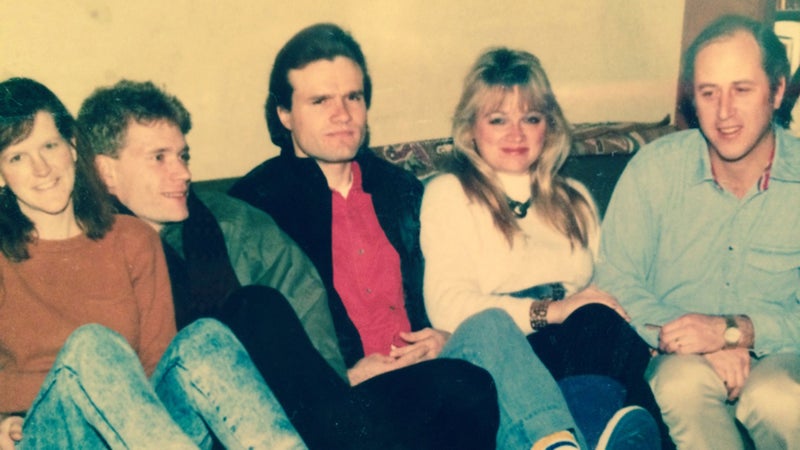

Life is complex, though. Many times during my visit, Chew is all lit up—bright-eyed, zany, and on. My second day there, he subjects me to what he calls his “RTP” mode of conversation, short for “Random Thrust Process,” asking me scores of questions—about my relationship history, my shoe size, my political views, my exercise regime—and scarcely ever awaiting an answer. He says he gets his eccentricity from his late father, Hal, a special-education Ph.D. and a proud freak—a vegetarian, a yogi, a devotee of Transcendental Meditation, and a man whose shag-lined Ford van bore a handmade wooden trailer capable of towing 13 bicycles. Hal Chew, he says, was a sort of guru. He was beloved by every hitchhiker he picked up on road trips, and in his basement, hanging barbells from two-by-fours, he built a bare-bones gym that carried his two sons to cycling prowess. (Danny’s older brother, Tom Chew, was a member of the U.S. Olympic development team in the 1980s.)

The talk turns to romance. Chew tells me that his first kiss came when he was 27—and that he bowled his date over. “She got down on her knees, this beautiful woman,” he tells me, “and she says, ‘Do you want to make love?’ I said no—no way. I love being different from the masses, and being a virgin was just another way I could be different.”

My second day there, he subjects me to what he calls his “RTP” mode of conversation, short for “Random Thrust Process,” asking me scores of questions—about my relationship history, my shoe size, my political views, my exercise regime—and scarcely ever awaiting an answer.

When Chew was 38, radio shock jock Howard Stern invited him on air. The segment was entitled “Pick the Virgin.” Stern shouted at Chew: “You’ll never get a woman! You’ll die a virgin!”

“That motivated me to spite him,” Chew says. “Within four months, I was in Oregon, living on a houseboat with this woman, and it was really nice. Whenever I came back from a ride in the rain, she’d have put warm blankets out for me.” The relationship was brief, and Chew doesn’t linger on it, reverting, instead to RTP mode, delivering me advice about matrimony—“Never marry anyone before you’ve lived with them for three years!”—before segueing into personal finance.

“Never ever eat a meal in a restaurant!” he says, shaking his index finger at me. “If you leave a two-dollar tip—that’s money that could be invested. And when it comes to cutting your hair, just buy a $20 clipper from Wal-Mart. How much talent does it take to shave your head bald?” The man is resolute about living life on his own terms.

Weeks pass. On Facebook, Chew’s older sister, Carol Perezluha, a professor of math at Florida’s Seminole State College, posts a video of her brother being rolled along a Chicago bike path looking out on Lake Michigan. He’s elated in the clip, saying, “This is the furthest I’ve been out on the wheelchair since I was hospitalized.” An accompanying photo shows him canting his feet skyward in his chair, lakeside, so he can regulate his low blood pressure. The blood pressure remains a concern. It is still erratic. “Sometimes it gets so low he blacks out,” his sister tells me. Once it spiraled so high that a host of caregivers rush toward his bed, hovering. He is also having trouble regulating his body temperature. Sometimes, even after he asks aides to bring him four blankets, his teeth chatter as he shivers in his bed.

Pre-accident, Chew suffered from occasional lightheadedness. The undiagnosed condition caused his crash. Is he fated to have a worse case of orthostatic hypotension—poor blood pressure regulation—than most paralyzed people? Dr. Roth doesn’t think so. “His problem is very common for patients with spinal injuries,” Roth says. “It’s something that over time he can manage, by wearing tight stockings, for instance, and abdominal binders.”

Still, for Chew's family—a loving group who once spent summer weekends together, riding—the crash is a nightmare that has thrown his two siblings into a search for a wheelchair-accessible van, handicapped-friendly housing, and ongoing care. His sister tells me that their mother, now 84, has been in “an awful state” of late. “Every day, she tells me she wishes it didn’t happen. She’s become disoriented.”

There are promising signals too, though, and when Chew phones me (the calls come in at odd hours: 6:48 am, 10:11 p.m.), his news breaks are triumphs: “I can transfer myself out of bed now,” he says. “I rode my wheelchair nine laps through the hallways. It’s nineteen laps to the mile. I did the hand cycle for an hour.”

A plan gels for his release. He’s slated to leave RIC on December 5, and this winter he’ll live with a friend in eastern Ohio. This friend, it so happens, owns a gym, and Chew is already looking forward to the track there.

On November 14, his physical therapist, Kate Drolet, tells me, “Danny’s improved immensely. He’s got a motorized wheelchair now and he’s completely independent on it. He goes all over the floor by himself, and after the Cubs won the World Series, we went to the victory parade. Even in the crowds, he didn’t need any help navigating. He is one of the most motivated patients I have ever seen. He is very intent on setting personal goals. He loves numbers.”

A plan gels for his release. He’s slated to leave RIC on December 5, and this winter he’ll live with a friend in eastern Ohio. This friend, it so happens, owns a gym, and Chew is already looking forward to the track there—it’s nine laps to the mile. Meanwhile, Pittsburgh firm Desmone Architects has stepped forward, offering to redesign the family's home to make it suitable for Danny and his aging mom. The construction will cost over $100,000. “Between Danny’s mind and Mom’s body,” Carol Perezluha says, “I think they can do it.”

Dr. Roth predicts that Chew should be able to get out on the roads, on a hand cycle, roughly a year from now, and a Pittsburgh friend is standing by, ready to serve as Chew’s coach. Attila Domos is a paraplegic. A 48-year-old onetime bodybuilder who fell from a ladder in 1993, Domos handcycled 407.7 miles inside 24 hours last August. When I call him, he is effusive with praise for Chew. “Danny trained me,” he says. “He told me that when you’re doing a 24-hour-ride, the night goes on forever. And he was right.”

Another of Domos’s remarks lingers most, though. “Recovery has almost nothing to do with how hard you work,” he tells me. “After my accident, I stood for three or four hours a day, hoping that feeling would come back to my legs. It never did.”

What if Danny Chew doesn’t recover enough to hand-cycle great distances? I ask him. “That’s not an option,” Chew says. “I’ve already ridden the wheelchair half a mile, and Attila tells me that translates to three miles on a hand cycle. He said he hates wheelchairs—that he’ll never do another marathon in a wheelchair. “Look, I’m just at the beginning of my recovery. I’ll get there.”