“Thomas Camero is three days behind you,” read the text. Barton Cohn rolled his eyes.

When Cohn set off to bike-tour the ��in 2016, he hadn’t realized that the trail’s eponymous bike race would be happening at the same time. And he hadn’t known that his friends back in Hood River, Oregon, were planning to keep him updated on it.

“Well, I’m not racing,” he shot back. But word kept trickling in that this guy Camero, also from Hood River, was 75 years old. And��despite losing the race, he was gaining on Cohn.

Everywhere Cohn went, the name followed. To hostels and guest houses. Gas-station mini-marts. A : “Have you seen Thomas Camero?” Cohn shook his head as he rode. Who was this guy, anyway?

When Cohn pedaled into the small town of Damascus, Virginia, a man shouted after him from a front porch,��“Is Thomas Camero with y’all? We really like that guy!”

By that point, Cohn had changed his mind. He was racing, and he was racing one man only: the mysterious Thomas Camero.

Thomas Camero doesn’t look like a legend. He doesn’t look 78 years old, either. Mostly, he looks like a giant smile that’s procured a set of arms and legs to get it from place to place. If you stare a little longer, you’ll maybe notice the wire-frame glasses��or the ears that stick out a little from under his helmet. But mostly, you’ll notice the grin.

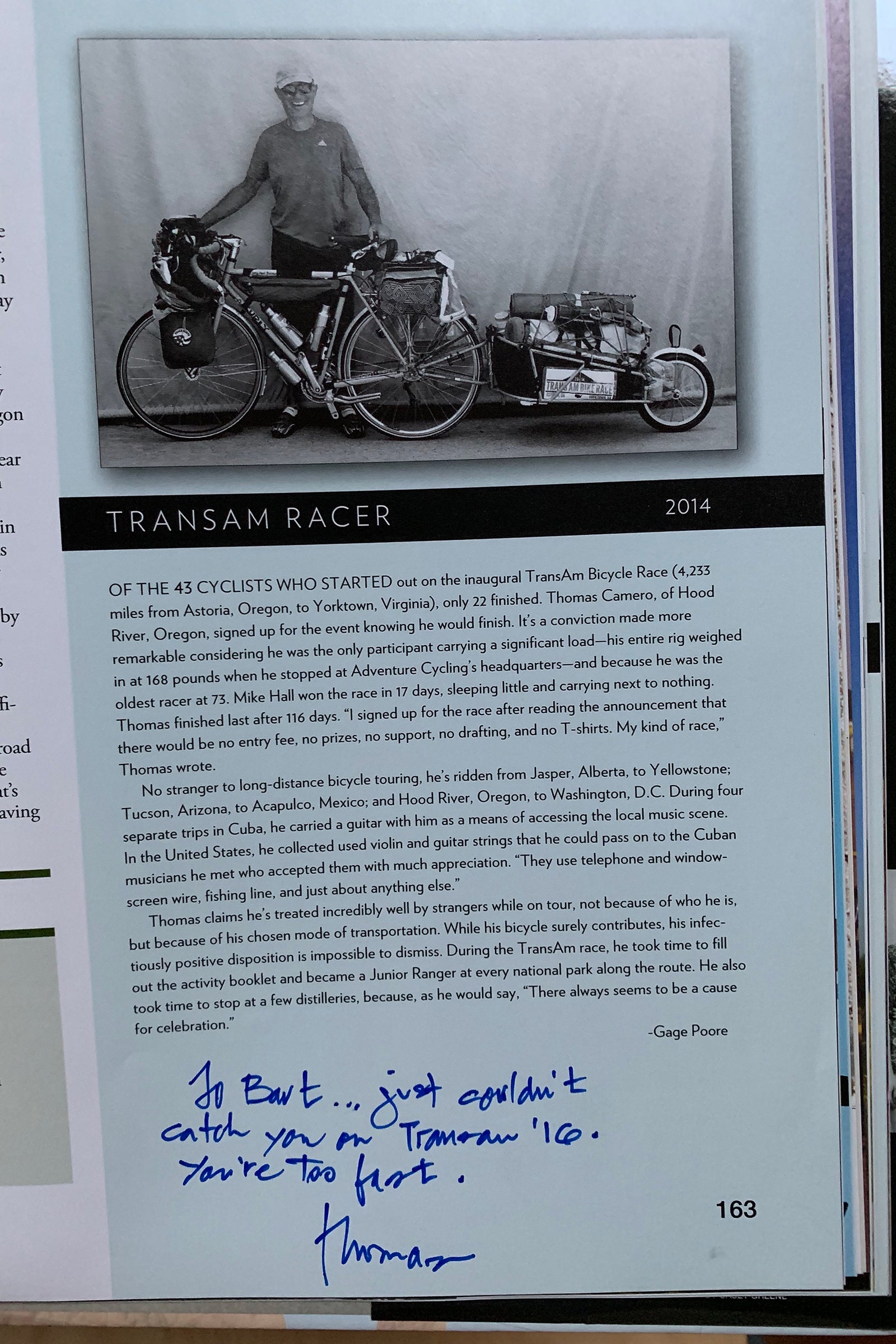

The arms and legs straddle a lopsided heap of mismatched gear that nearly hides the bike underneath, a . Camero got it secondhand for $700.

“I call it Old Growth,” he says. “It’s sprouting all kinds of different bags and whatnot.”

On September 9,��Camero finished his third ��after 99 days of riding. Again��he was the fan favorite. And again��he finished in last place—a full 58 days after everyone else. Despite his pace, Camero was likely the most experienced bikepacker in the race. After all, he’s had the touring bug for more than half a century.

In the 1960s, Camero pedaled from Tucson, Arizona, to Acapulco, Mexico, with nothing but $72 in his pocket. Later��he sold his bike, flew to Bogotá, bought a new one, and pedaled to Lima, Peru. Since then��he’s toured across North America, Asia, and New Zealand.

A few years ago, Camero pedaled the length of Cuba. At the time, it was notoriously difficult for Cuban artists to find guitar strings. A guitar player himself, Camero collected used strings before heading south. He passed them out to musicians as he rode.

His adventure addiction has taken other forms��as well. Camero was a ski bum in Taos, New Mexico, in the ’60s and a Peace Corps volunteer in Honduras in the late ’70s. He spent seven years building small airports along the Iditarod��Trail and throughout the Alaskan interior. More recently, he’s taken on engineering projects in Afghanistan and South Sudan.

“So many people wait until they retire to do things��and then have a massive stroke or something that keeps them from living out their dreams,” says Jane Camero, Thomas’s wife of 31 years. “Tom has never been the sort to wait for a certain age or stage to do things. He finds a way to fit them into the present.”

After a brief detour into marathon running, Camero found that he missed multi-day adventures. So��when he got invited to a Peace Corps reunion in Washington, D.C., in 2011, he decided not to buy a plane ticket from Oregon. Instead, he biked there.

Thomas Camero doesn’t look like a legend. He doesn’t look 78 years old, either.

Camero enjoyed the ride from Hood River to D.C. so much��that when word of a new cross-country race came along, he knew he had to do it. The first Trans Am bike race, which would follow the TransAmerica Trail from , was scheduled to take place in 2014. Camero called up the race director, Nathan Jones, immediately.

He knew Jones was looking for riders who could complete it��in a month or less. “But for me, it’ll be more like 80 days,” Camero said on the phone.

Jones was unfazed. He said he’d hit the stopwatch . “However long it takes,” Jones said.

That year, Mike Hall won the race in . Meanwhile, it took Camero just shy of four months.

“I went as fast as I could. I just couldn’t believe how hard it was,” he says.

But in Camero’s mind, he was never in last place. Ask him about it, and he’ll point to the dozens of riders every year who scratch.

“They start so fast and burn out and get discouraged,” Camero said. “Me, I don’t book a plane ticket. I don’t have anyone to meet or anywhere to be. I just show up and ride.”

“He’s definitely competing, but only with himself,” Cohn says. After the 2016 race, Cohn made a point of meeting Camero, who never did pass him. The two have since become friends. While Camero loves the edge and energy that racing adds to touring, he said he’s conscious of setting realistic goals for himself.

“He doesn’t expect to win, but he always expects to finish, and he pushes himself more than most people,” Cohn says.

Camero pulled his bike to the side of the road, laid��down in the weeds, and fell asleep. He woke up a few hours later as the sun rose. It wasn’t a heart attack after all. So he hopped back into the saddle and kept going.

“Thomas is one of the most charismatic people you’ll ever meet,” Jones says. “He gives you a hug whenever he sees you. He’s just bubbling over with enthusiasm all the time.”

Camero’s love for the race—and for the community that has grown around it—is perhaps unparalleled. This year��he carried a huge hardcover book with him, a . He got everyone he met to sign it.��

“People like Thomas make the sport what it is. He’s a huge part of this race,” Jones said. “And he’s somebody who’s definitely been there through some dark moments.”

In both and , Trans Am racers died in collisions with automobiles. Also , Mike Hall, who had become a big part of the Trans Am community, was .

Jones took the deaths to heart. He says he found himself questioning whether he should keep the race going. “But Thomas was there, talking about how much he loved the race and the route. He was there reminding me of those things when I was lacking a clear way forward,” Jones says.

Two years after the inaugural race, Camero returned to Astoria for a rematch. While pedaling��through Kansas, a few weeks into the race, he started to feel fatigued.

“I was thinking maybe it was another heart attack,” he says. He’d suffered��one a few years back and eventually had a stent put in. (According to Cohn, Camero shrugged off the first, saying, “You can’t let that stuff slow you down.”)

Camero pulled his bike to the side of the road, laid��down in the weeds, and fell asleep. He woke up a few hours later as the sun rose. It wasn’t a heart attack after all. So he hopped back into the saddle and kept going. “I didn’t think much of it. Too fun riding,” he says.

That year, at age 75, Camero shaved 19 days off his 2014 time.

This year��he was after a new personal record, which he missed by just two days. Followers of the race, affectionately known as “dot watchers,” have joked that it’s because he spent too much time stopping to swap stories with his adoring fans. But that gives little credit to Camero’s pain tolerance: according to Jane Camero, doctors told Thomas he was supposed to have both knees replaced 15 years ago. “I think he’s planning to use them all the way up first,” she says.

Camero says he had to increase��the dose of��his pain��medication over the course of the race. And in August, he hit a curb and crashed his bike, leaving him with severe road rash. Jane says she’s started to worry about his ability to recover before the rides in New Zealand and Asia he has planned for the coming year.

��

According to Cohn, physical pain is only a small part of self-supported bike touring. When you’re grinding down highways and isolated country roads with no idea where you’ll sleep, it gets lonely. When your bike breaks, you fix it. When you ride into the night, you set up your tent in the dark.

“It’s a big country, and you’re just one person on a bicycle,” Cohn says. But if you scroll through the past three months of commentary on the official , you’ll find nothing but comments about Camero. Of anyone in the race, he has the biggest fan club by far. In that way, he’s never quite alone.

“I think he knows there are all these people following him and, in a way, depending on him. And he’s got friends in every town along the route,” Cohn says. “I think that keeps him going.”

For the last two months, Camero has been the only competitor on the course. It’s fitting; this whole time, Camero has been racing no one but himself��anyway.

He spent the last two weeks battling through the Appalachians, in what Jones calls “dog-ridden hill country.” Camero��sees the region a little differently.

“There are people stopped on the side of the road and people who come up just to ride with me,” he says. “It’s this big family. It’s just wonderful.”

And though Camero was competing, and though he was aware every day that he was falling more behind in his quest to beat his 2016 race time, he still stopped for everyone who wanted to meet him. He offered training and touring advice. He got his book signed.

At the end of the day, he says, those moments are more important than beating a time. “Every day is so filled with goodness, I can’t stand it,” he says. “How could I think I’m not a winner?”