The initial shock of theĚýcoronavirus might be wearing off, but the world’s new reality—in which we’re still sheltered in place, no cure or vaccine exists, and entire industries are shuttered—can cause stress we feel unequipped to deal with. Mountain guides are no exception, with scheduledĚýclimbs and expeditions to places like Mount EverestĚýand Denali canceled for the year.

To help, the American Mountain Guides Association recently published “,” a set of mental-health resources created by Laura McGladrey,Ěýa National Outdoor Leadership School (NOLS) instructor and nurse practitioner who specializes in emergency medicine and psychiatry. She’s been studying the impacts of trauma on first responders and other outdoor providers since 2012Ěýand has advised organizations including , , the National Park Service, and the AMGA on how to alleviate those impacts and protect the mental health of their employees.

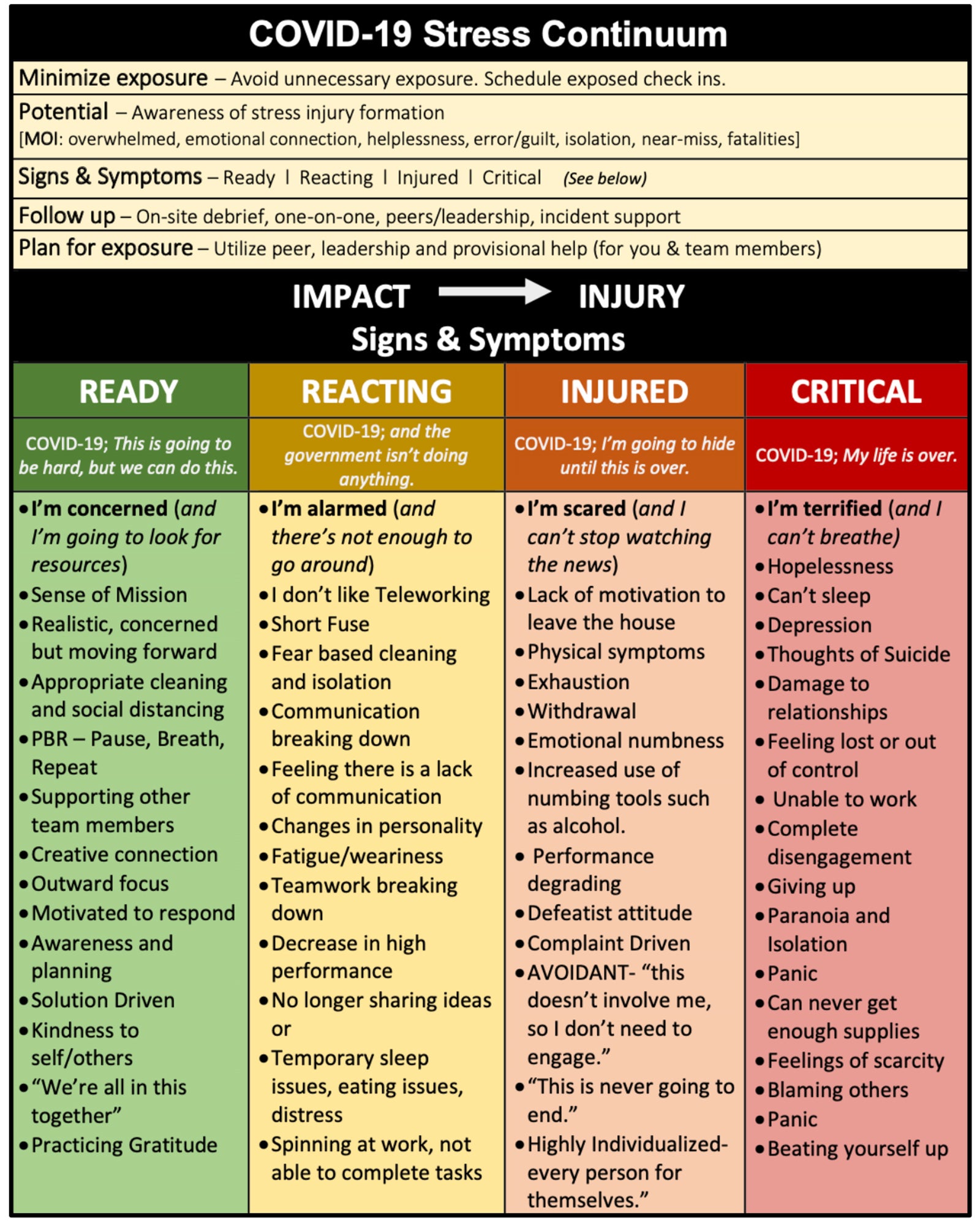

Included in the resources shared by the AMGA is McGladrey’s “CovidĚýStress Continuum,”Ěýwhich was adapted from a modelĚýdeveloped by the Ěýand Ěý(the Responder Alliance and National Park Service also contributed to McGladrey’s version).ĚýThis toolĚýhelps to assess how impacted an individual is by the stresses of the current upheaval. Exhibiting reactions in the “ready” stage, for example, would indicate a psychologically healthy response; behaviors in the “critical” stage might indicate what McGladrey calls a stress injury, requiringĚýprofessional support.

“The idea was to show that, during this pandemic, everyone is going to be stress impacted,Ěýbut that they can prevent themselves from becoming stress injuredĚýby assessing their state of mind and taking steps to protect their mental health,” says McGladrey. Her accompanying article, “,” also published on the AMGA site, outlines a resiliency planĚýwith practical guidelines. The following tips, adapted from this paper, can help both mountain professionals and ąú˛úłÔąĎşÚÁĎ readers alike get through this time in the healthiest way possible.

1. Build a psychological first aid kit.

McGladreyĚýrecommends creating a psychological first aid kitĚýor a plan that, according to her paper, incorporates practices that “are known to support and mitigate traumatic stress in real time.” The principles of psychological first aid, says McGladrey, are safety, calm, connection, efficacy, and hope. (Ways to promote each element in your day-to-day follow.)

Write your plan down: Which elements of psychological first aid will you perform regularly? Then create accountability or friendly competition with others; for example, exercise is a practice that contributes to calm and efficacy. You might check in with your family daily to make sure everyone is exercising.

2. Seek out reminders of your safety.

One way to create a sense of safety, says McGladrey, is to avoid misinformation and fearful stories. The news, the internet, even your friends are rife with both of these; your job is to learn only what you needĚýfrom reliable sources and to shut out extraneous information. “What the Denali climbing rangers have done is designate one person, in their case flight medic Dave Webber, to scour the internet and brief the rest of the team on new developments,” says McGladrey. “This insulates the team from a continual flow of bad or alarming news, which can tell your brain you’re in constant, immediate danger.” Be your own gatekeeper by limiting your news or social-media checks to once a day. Choose one reliable news source and stick to it. And focus on the fact that you’re relatively safe in the moment. “Think, I am safe. I do have enough to eat. I may have lost my job, but I still have a roof over my head,” says McGladrey.

3. Create “corona-free zones.”

Find ways to be fully in the moment. “Staying present regulates and downshifts your nervous system,” says McGladrey. Engaging in an activity that’s unrelated to COVID-19, like reading or bakingĚýor “something as simple as playing UNO Flip with a kid, can help your nervous system relax, whichĚýboosts your immune system,” she adds. (Stress has been linked to Ěýand evenĚý.)

If you can’t limit your social-media and news intake to once a day, McGladrey advises creating “corona-free zones”—blocks of time when you don’t check email, social media, or texts at all. Similarly, she says, create a window each day during which you give yourself permission to take care of only yourself and your family. She calls thisĚý“staying in your lane.”

4. Plan calm into your day through exercise, sleep, and deep breathing.

At least once a day, plan to doĚýanalogĚýactivity that doesn’t involve sitting in front of a screenĚýand that helps your body relax, says McGladrey. It can be showering, baking a cake, or—for us outdoorsy types—a regular movementĚýlike casting a fly rod. Exercise, even if that meansĚýjust getting out for a walk. Get enough sleep, ideally eight hours per night. Sleep is restorative, , and allows our subconscious ,Ěýshe says. And take time each day to focus on your breathing, such as in meditation: “When you exhale long, slow breaths, it activates your parasympathetic nervous system, which secretes hormones that tell your body to slow down,” she says.

5. Boost your efficacy.

Efficacy is defined as the ability to produce a desired or intended result. “One thing guides and a lot of other outdoor folks are feeling right now is a loss of identity, because we can no longer engage with our lifestyles or even go to the places we normally do to find solace,” says McGladrey. But there are a lot of things you can do while sheltering in place to remind you of your efficacy. Plan and execute a meaningful project, like building an outdoor compost area. Organize your shed. AssembleĚýpiles of gear you want to unload at a garage sale. Start mapping out a giant backcountry trip you want to do once the shelter-at-home order is lifted. And for guides or others who have lost jobs: “Seek the information you need to understand the future and make a plan,” she says. “If you are knowledgeable on these matters, share [them] with friends and family.”

6. Help others.

Remind yourself that your actions can contribute to the greater good. Helping others is what McGladrey calls “the ultimate efficacy.” In her paper, she writes, “This tells your brain that not only can you get yourself out of this, but you have enough for the people around you….ĚýIt is the antidote for the feeling of scarcity and fear.” Offer to run an errand for an elderly neighbor. Give an encouraging call. Host a virtual story time for your child’s friends. Donate much needed blood (visit theĚýĚýto find a locationĚýnear you).

7. Cultivate hope.

“How do you plan for hope? In times of uncertainty, it can start to feel like there’s no moment but this one,” says McGladrey. But planning for the future can be an empowering act of defiance. She suggests planting seeds so you can look forward to them sprouting, sharing positive stories with one another, or starting a gratitude journal with a faraway friend—it cultivates connectionĚýand wires your brain to look for the good in life. Reassure yourself that this is a changing situation. “This is a grief process,” she says, “but we are moving through.”