A few years ago, researchers nine years of detailed training and health records from Norway’s world-beating cross-country ski team, seeking to understand the difference between Olympic and World Championship medalists and their very-very-good-but-not-quite-podium-caliber teammates. One of the key patterns that emerged: medal winners spent an average of 14 days per year with colds and other minor infections, while also-rans averaged 22 days.

Staying healthy is vital to athletic success, both during the months of hard training and in the stress of competition, which often involves travel, jet-lag, shared accommodations, and other risk factors. A in the British Journal of Sports Medicine offers a glimpse from the trenches, with a report from the medical team that accompanied Team Finland to the 2018 Winter Olympics in South Korea on their efforts to diagnose and limit the spread of the common cold using new real-time testing.

The study followed 112 people (44 athletes, 68 support staff) who were at the Olympics for an average of three weeks, mostly living in a single block of apartments. Anyone who had a respiratory symptom—sore throat, runny nose, congestion, cough—immediately had two mucus specimens taken with nasal swabs. One was fed immediately into the machine, which takes 30 minutes to tell you whether you’ve got the flu or certain cold-causing viruses. The other was stored until the team returned to Finland, then analyzed with a more rigorous to confirm what viruses were present.

The first thing that popped to mind when I read the abstract of this study is: why bother? Who cares which particular virus you’ve got, given that we don’t have effective cures for any of them? But that’s not quite true. For one thing, it’s very useful to know immediately whether your sore throat is a virus or a bacteria like strep throat; if the latter, then you should get on antibiotics ASAP. It’s also possible—though —that if you have a flu virus or have been exposed to someone who has it, then you might benefit from taking Tamiflu.

This latter approach is what the Finns opted for. A total of 42 out of 112 people (including 20 of 44 athletes) reported respiratory symptoms during the Games. The symptoms were mostly mild, but the rapid point-of-care testing flagged six cases of influenza virus. All were treated with Tamiflu, along with 32 other people who’d been in contact with them. It’s impossible to know whether this lessened the symptoms or spread of the outbreak, but in theory it may have helped.

The common cold was less effectively diagnosed with the rapid testing, which only picked up five cases of respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) A. The later PCR testing ended up identifying infections—coronaviruses, rhinovirus, human metapneunovirus, etc.—in 30 of the 42 cases. This is interesting because some previous studies have failed to find viruses in a large proportion of athletes who report respiratory symptoms. That suggested these symptoms are often the result of non-infectious airway inflammation, perhaps from lots of heavy breathing. In this case, though, it appears that most of the Finnish athletes really were sick.

The most interesting part of the study is the analysis of how the infections spread. There were seven different clusters of specific viruses, and these clusters tended to form within a given sport or event group. In other words, not surprisingly, sick athletes were passing it on to their teammates. The medical team did attempt to isolate athletes who reported sickness for three to four days, which may have reduced further spread but wasn’t enough to stop it entirely.

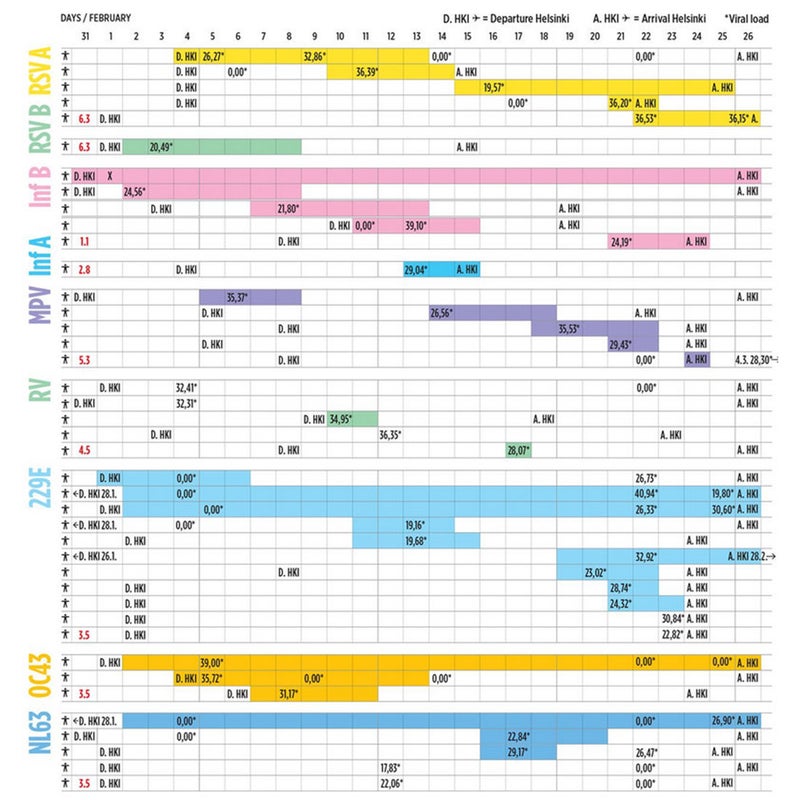

The graph below gives a bird’s-eye view of how infections spread during the Games. Each color represents a different virus strain; each row represents a different athlete; and each column represents a day. (The entire article is , if you want more details.)

For several of the viruses, like RSV A and influenza B, you can see how they start with one person, then spread to another and another and another. The stories behind each virus are fascinating.

For example, one subject reported congestion before leaving Finland, and was subsequently diagnosed with RSV A in the Olympic Village. But by then it was too late: the person sitting next to Patient 0 on the nine-hour flight to South Korea was diagnosed with the same strain six days later. Someone else got it—perhaps from the second patient rather than the first—10 days later, and two more got it 16 and 17 days later.

There was a similar story for the flu. One person developed symptoms, including fever, on the flight to South Korea. They were later diagnosed with influenza B. In this case, the person sitting behind the initial patient then came down with the same strain of flu 1.5 days later. There were three further cases of the same strain, though it’s not clear if they were connected to the initial outbreak.

Overall, most of the infections appeared to originate in Finland. Once the athletes and staff were in the Olympic Village, they were probably hyper-vigilant about hand hygiene and avoiding crowded places and so on—if only because a team of doctors kept following them around and threatening to stick swabs up their nose. But they may have been a little less vigilant back in their home environments before they left. That’s perhaps one useful lesson to keep in mind.

And there is one other, slightly happier story. Yet another person developed symptoms—nasal congestion, this time—on the flight to South Korea. Upon arrival, a swab determined that they had RSV B. But there was a difference this time: unlike the other patients, this one was seated in business class. After arrival, the patient was isolated for four days, and no one else on the team developed this particular infection. Whether you’re an athlete, a business traveler, or (say) a journalist on assignment, the message is clear: if someone else is picking up the dime, demand business class. Your health and success may depend on it.

My new book, , with a foreword by Malcolm Gladwell, is now available. For more, join me on and , and sign up for the Sweat Science .