It’s summer trip-planning time, and I’ve been fretting over the tiny black squares on my canoe route maps. Cabins! The last thing I want in the middle of a backcountry adventure is evidence that I’m not actually the first person (other than the mysterious fairies who clear portage trails and campsites) to pass through this particular slice of wilderness. Nature, I’ve always figured, should look as natural as possible.

But would the glimpse of a building or road really harsh my vibe? A in the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, from scientists at two Austrian universities and with funding from the Austrian Alpine Association, explores precisely this question.

The researchers sent 52 volunteers to spend three October days in “a renowned summer and winter sports area” in the Austrian Alps. On back-to-back days in random order, they did two hikes that were as identical as possible—a bit more than 4 miles, climbing and then descending about 2,500 feet, taking about three hours, walking at similar speeds—with one crucial difference. One of the hikes took place in an area with virtually no signs of human habitation, while the other was continually in sight of features like a highway, ski lift, snow cannons, construction sites, and a parking lot. The purpose of the study wasn’t disclosed, so the subjects weren’t alerted to the differences between the two hikes.

The key outcome measures were a series of questionnaires to assess feelings like anxiety, elation, anger, calmness and so on, plus a series of spit tests to measure levels of the stress hormone cortisol. There’s plenty of previous research backing the idea that spending some time being active in a natural environment can alter these variables for the better, and (as I’ve written about previously) a few hints that wilder nature might pack a bigger punch. That’s certainly what my canoe-trip-planning intuition tells me.

The unanswered question, though, is whether we respond mostly to the positive attributes of nature, or to the negative effects of man-made environments. Do we love trees, hate skyscrapers, or some mix of the two?

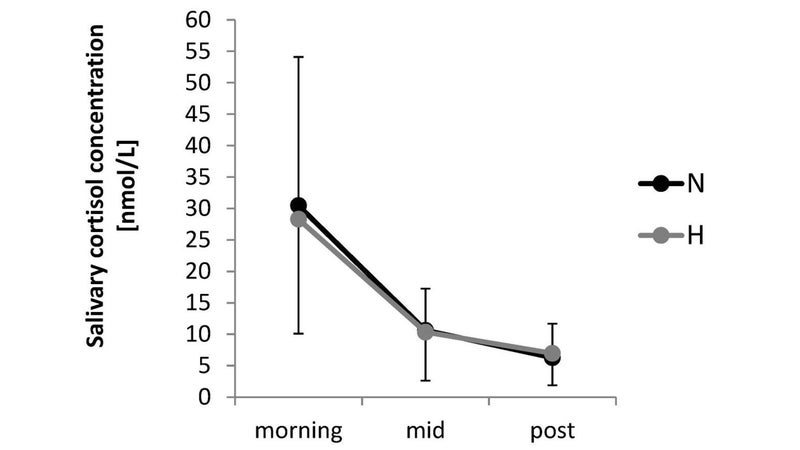

The results of the Austrian study suggest that getting into nature is great regardless of the presence or absence of manmade features. The cortisol data, for example, showed a nice drop from pre-hike to mid-hike, and a further drop by the end of the hike—but no differences between the two hikes:

It’s worth noting that other factors like circadian rhythms affect cortisol levels, so some of the decrease may simply be due to time of day. But the absence of any difference between the two groups is the key point.

The volunteers’ moods also changed more or less as expected, with an increase in positive feelings like elation and a decrease in negative feelings like anxiety after the hikes. But once again, there was no statistically significant difference between the two hikes: seeing a highway or a ski lift didn’t make the experience any less beneficial.

Of course, not all man-made structures are equivalent. The researchers acknowledge that things like ski lifts and snow cannons actually have very positive association for many people, which might skew the results. The findings might have been different if the hike had wound past a garbage dump or an open-pit mine—or, god forbid, a cell tower reminding them of all the unanswered emails waiting for them back in civilization.

One additional wrinkle: the subjects were also asked how they thought the hikes had affected their mood, with the following question: “How did the environment of the mountain hiking tour influence your well-being?” (It probably reads a little more smoothly in German.) On a scale of 1 to 10, with 10 being the most positive, they rated the more natural hike 8.5 and the human-influenced one 6.3. Like me, in other words, they liked the idea of seemingly untrammeled wilderness, even if it didn’t have any clearly measurable physiological or psychological effects.

In the end, that conscious preference isn’t necessarily something to ignore. For whatever reason, I love getting as far as possible from signs of human habitation. But studies like this have helped me be a little less dogmatic about it. Even though I live in a city of 4 million, I bought a used kayak last fall, figuring that frequent short paddles on the semi-urban river a couple of blocks from my house are better than waiting all year for a single epic trip. And as I plot a relatively easy route to explore with my 3- and 5-year-old daughters this summer, I’m realizing that we’ll probably have to accept some black squares on the map. As long as there’s no cell service, we’ll be fine.

My new book, , with a foreword by Malcolm Gladwell, is now available. For more, join me on and , and sign up for the Sweat Science .