The income gap is , and it turns out that it may be making us less healthy.

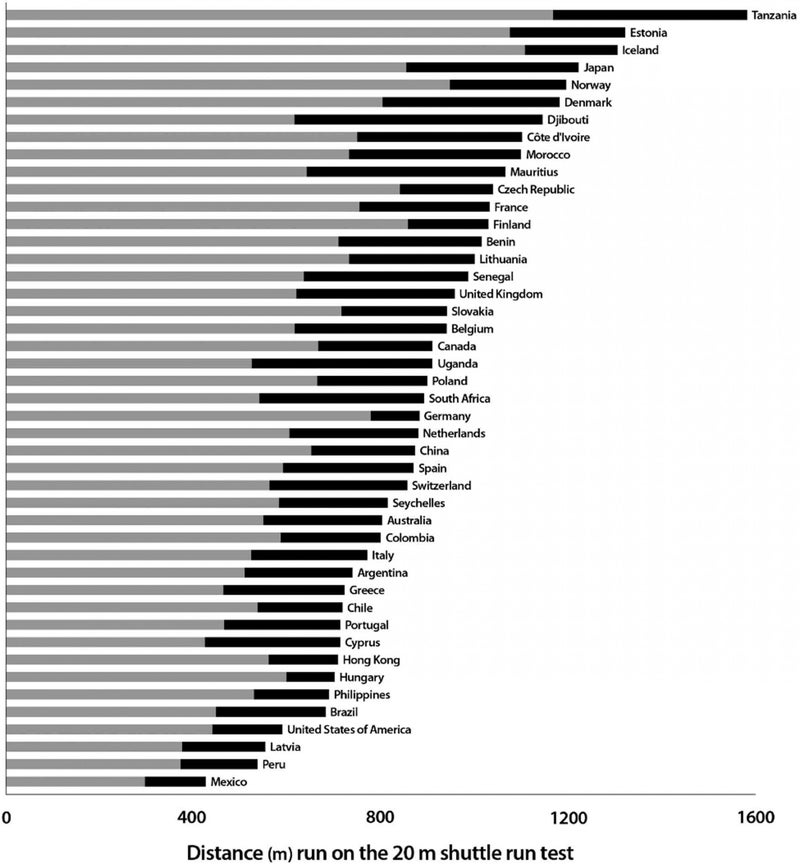

In a published this past August in the British Journal of Sports Medicine, researchers combined data from 177 previous studies conducted around the world to better understand the link between a countryтАЩs income inequality and youth fitness. Specifically, the researchers compared a countryтАЩs Gini Index, which measures how income is distributed throughout a nation, with childrenтАЩs performance on the 20-meter shuttle-run test in that same country. They found that the greater a countryтАЩs income disparity, the less likely their children were to do well on the shuttle run.

The premise of the shuttle run test, which you might remember taking in grade school, is simple: Two parallel lines are drawn 20 meters apart. The children must run back and forth between them, reaching the next line before a beep sounds. The time between beeps decreases as the test goes on, forcing the kids to run faster. If a child fails to reach the opposite line before the beep sounds twice in a row, he or she is eliminated. Because the standardized test is popular around the world and because many children can be tested at once, scientists can draw conclusions about a countryтАЩs level of youth fitness by pooling enough shuttle-run data.

It seems that poverty tends to make people less fit primarily when they live in a relatively rich country.

тАЬThis is a really powerful study,тАЭ says David Lubans, a researcher at the University of Newcastle Australia who was not involved in the study. тАЬWe canтАЩt infer causation, but weтАЩre looking at such a large number of data points that you can have some confidence in whatтАЩs being said.тАЭ (As Lubans points out, itтАЩs important to note here that the researchers have discovered a correlation between income inequality and fitness.)

тАЬWe know that when thereтАЩs a large gap between rich and poor in a country, there tend to be large subpopulations of poor people within that country,тАЭ says Justin Lang, the first author on the new paper and a PhD student studying population health at the University of Ottawa. тАЬPoverty, we know, is linked with a whole bunch of poor health outcomes. One of those outcomes is poor aerobic fitness in children.тАЭ The link between obesity and cardiorespiratory fitness lies at the heart of this discussion, and while itтАЩs perhaps unsurprising that being overweight has a negative impact on fitness, the real question at the center of the matter might be, тАЬWhat does income inequality have to do with obesity?тАЭ

The answers to this question are simultaneously complex and intuitive. тАЬThe most obvious and commonly put forward suggestion is that when youтАЩve got a group of people with low income, then theyтАЩre more likely to be in an obesogenic environmentтАФone where they donтАЩt have access to healthy food, for instance,тАЭ says Timothy Olds, a researcher the University of South Australia who has been studying the link between income inequality and fitness for more than a decade. тАЬThey have access to cheap but very high-calorie, energy-dense food, and they donтАЩt have access to things like parks or walkable neighborhoods.тАЭ

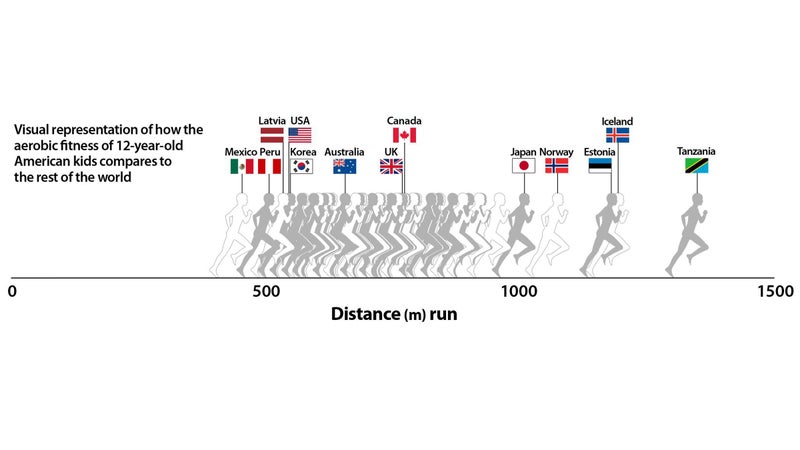

This ideaтАФthat poorer people donтАЩt have access to healthy lifestyle choicesтАФisnтАЩt revolutionary, but as the figure from the paper below shows, kids from plenty of poor countries (like Tanzania) scored extremely well on the shuttle-run tests. тАЬOne thing we do know is that those countries that are generally quite poor, like a lot of the African nations, particularly the developing ones, is that they donтАЩt have the good parks and playgrounds and equipment and facilities,тАЭ says Grant Tomkinson, also from the University of South Australia. тАЬTheyтАЩre almost physically active out of obligation. So they have to walk or cycle to and from work. They have to walk over a greater distance to access fresh water or groceries, for example.тАЭ

The distinction between the developed and developing world seems central to explaining the fitness trends that the new study reveals. While in developed countries the poorer people tend to be less fit, the opposite is often true in undeveloped ones. тАЬThereтАЩs a thing called the physical activity transition,тАЭ says Olds. тАЬIn poorer countries, itтАЩs the richer people who tend to be fatter, and the poorer people tend to be leaner and fitter. Then, in the middle, you get countries that are in a certain point on their developmental trajectoryтАФwe found this with Colombia and with India, for exampleтАФwhere itтАЩs basically dead even; the level of fatness is the same in the poorer and richer people.тАЭ

It seems, in other words, that poverty tends to make people less fit primarily when they live in a relatively rich country. Being poor but surrounded by fast food, automobiles, and television is more detrimental than being poor in a rural environment where physical activity is a necessary part of daily life.

Again, these data reflect only a correlation, not causation. But performing more rigorous experiments, like a randomized control trial, can be logistically and ethically tricky for researchers. тАЬYou canтАЩt take a kid from an environment of equal income and put them in an environment of unequal income and see what happens,тАЭ says Olds. Instead, he suggests they strengthen their findings by tracking the change in the Gini Index against the change in youth fitness over timeтАФa project he hopes to start in the future. тАЬIf itтАЩs true that as societies become more unequal, kids become less fit, that would be interesting,тАЭ he says.

тАЬNatural experiments could also help us shore up the findings,тАЭ says Lubans. тАЬWe could work with schools in terms of delivering whole-school interventions that try to get kids more active and try to improve their fitness levels, and then explore the impact of that on outcomes. ThereтАЩs such a great opportunity to have an impact on young peopleтАЩs current and future health by getting them more active.тАЭ