Is Nature the Key to Rehabilitating Prisoners?

Once released, the formerly incarcerated face a daunting set of challenges—a job, a place to live, and, most urgently, breaking the cycle of bad friends and bad habits that can lead to more prison time. Now scientists and activists are asking whether nature may be essential to helping them build new lives.

New perk: Easily find new routes and hidden gems, upcoming running events, and more near you. Your weekly Local Running Newsletter has everything you need to lace up! .

Rain-swollen and cloudy, the McKenzie River ran fast, and fat drops from a flint-colored sky dimpled the water. Brian* pushed his way along an overgrown trail to a small clearing on the riverbank.

He stepped onto the trunk of a fallen, half-submerged snag and edged along the rain-slick bark, a tightrope walker with a fishing pole a few miles outside Eugene, Oregon. At 39, he had spent much of his adult life in prison, mostly for drugs and theft. He had just finished a yearlong sentence for possession and wasn’t yet fully free, locked down at night but allowed out during the day for work release—or for an activity like this, which is considered therapeutic. The water on his right was quick. He flipped his fly into the deep water to his left, near the bank, and drifted it through the calm pocket.

“The solitude is such a good thing for me, and being away from the prison politics,” he said as he watched the water. “Being able to talk to normal people, who aren’t preying on people, talking shit, loudmouthing.” He brought in his line, the rod tip hovering just over the water. A trout nibbled, and he flicked his wrist to set the hook, but too soon.

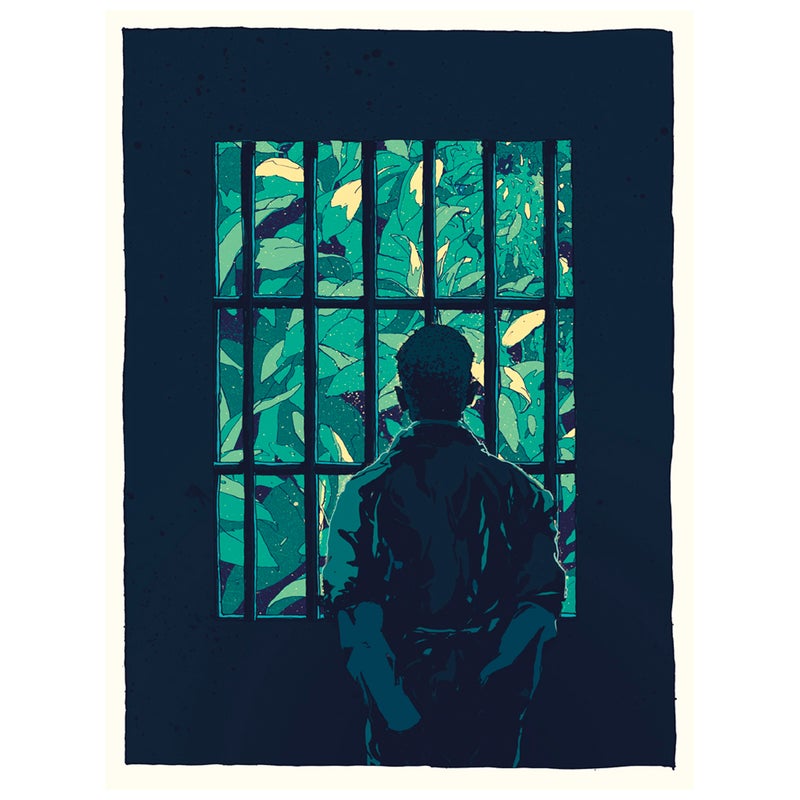

“You’re never alone. No privacy, no time to think. Even when you’re lying in bed, there’s someone making noise right next to you,” he said. “That’s something people take for granted, the solitude to reflect without reacting to something all the time.”

He worked the hole a while longer, then retreated down the path to rejoin the half-dozen others, more of society’s outcasts. Together they had spent decades in prison for everything from assault to failure to pay child support. Mike, 60 and heavy through the middle, with a deep voice, accounted for a good chunk of that tally: 34 years broken up over several stints. Among other crimes, he once threatened to kill President Bill Clinton. He now spends much of his spare time fishing and camping, and serves as a mentor for the recently released.

“No matter what society labels us, we’re free,” he told them. “We weren’t born with tags on us.” He’d been out of prison seven years and acknowledged that it hadn’t been easy. “At times,” he said, “I wanted to throw in the towel and go back.”

“Seven years?” Brian said. “That’s pretty good. I can’t go a year without getting caught back up in some shit.”

“What makes you fail?” Jen Jackson asked. Jackson runs the mentorship program at , an organization in Eugene that helps the formerly incarcerated relearn life beyond prison. For the past several years, she has organized regular outdoors trips, too.

“I hit the gate running, feeling like I have to make up for lost time,” Brian said. But the drugs and partying and poor choices had beat him down so far that he was looking for a change. “I’m trying to do some of these things,” he told Jackson, referring to today’s outing, “instead of getting back into the bullshit I was in.”

At least if he was fishing, he said, he wouldn’t be chasing dope.

Nearby, on a grassy patch along the river, Eric was dressed more for a coffeehouse poetry slam than a fishing trip, with black jeans and a turtleneck, wavy brown hair brushing his shoulders. At the Oregon State Penitentiary in Salem, where he served three and a half years for cashing counterfeit checks, a concrete wall blocked the views of the surrounding area. Many mornings, Canada geese landed in the yard, and he imagined himself among them, flying away and over the land to places like this. “There’s something about the sound and flow of water, the wind in the trees, the colors, the freedom, that gets a person to reflect on what’s important to them,” he said, “and maybe get back to the basics with their needs and the needs of the people around them.”

Sponsors runs one of the only programs in the country that takes formerly incarcerated adults into nature as part of a reintegration program. This needs to change.

That sentiment captures what science reconfirms almost weekly in study after study: nature is good for us. It can ease anxiety and depression, pull us from spirals of negative thinking, boost brain function, and improve our physical health. Just a short walk in the woods is enough to see benefits. Today there are countless programs that combine the restorative power of the natural world with outdoor activities—horseback riding, rock climbing, surfing—to promote well-being and even treat mental and physical traumas. So it makes sense that some experts are beginning to believe that time in the outdoors could also help stanch criminal behavior. Options abound for at-risk youth, from confidence-building challenge courses to extended wilderness trips paired with group therapy. Studies have shown that these can reduce a young offender’s likelihood to commit more crimes, improve judgment and decision making, and reduce depression, anxiety, and stress in adolescents with mental-health problems.

We generally regard children and teenagers as deserving of a second chance, their clay not fully sculpted. Adults who have served time receive far less understanding. “You have this scarlet letter on you,” a Sponsors client told me. “You feel everyone will do their utmost to hold you down. No one is going to forgive you. You’ll be forever judged.” Nature can provide an injection of calm. We know this as we breathe in the quiet of a park or flee the city for a weekend in the backcountry. We extol the power of the outdoors to bring balance and perspective. But is that benefit due only to the well-adjusted and trouble-free? Because here is a group that perhaps needs it more than any other. They are locked away from nature, sometimes for decades, then ostracized upon their return to society, where they often struggle to find housing, jobs, and friends. Yet Sponsors runs one of the only programs in the country that takes formerly incarcerated adults into nature as part of a reintegration program.

This needs to change. As you’ve likely heard, America has a prison problem, with too many people behind bars and too little help as they try to rebuild their lives on the outside. The U.S. accounts for 5 percent of the world’s population but 25 percent of its prisoners. That’s 2.2 million people held in federal, state, and local facilities. The vast majority aren’t serving life without parole, which means they’ll eventually be our neighbors. If we want to keep them out of prison and prevent them from committing more crimes, if we want to help them succeed, we need to rethink how they’re treated. And bringing offenders into the outdoors—even while they’re still locked up—may vent just enough steam from the pressure cooker to get them back on track.

��

Tony stabbed and wounded a man, served five years, and left prison in October 2013 with a cardboard box that held the entirety of his worldly belongings: his legal paperwork, some cards and letters from family, a coffee mug, a few toiletries, some pictures of friends and fellow inmates, and the black Nikes he’d bought at the commissary. All the rest—his clothes, furniture, family photos—were thrown away when the landlord cleared out his apartment.

After an 11-hour ride from eastern Oregon, the bus dropped Tony in Eugene, where he’d grown up, and he stood on the street alone. His mother had died while he was inside. Boyhood friendships had faded. But someone had come for him: the manager at Sponsors, who took him to Taco Bell for three tacos and two bean burritos, and then to 7-Eleven, where Tony bought a Coke Slurpee with some banana syrup mixed in.

From there they drove to a light-industrial area on the outskirts of Eugene, to a small compound of brightly colored buildings surrounded by rich landscaping meant to counter the drab tones of prison. Tony would live here for the next 90 days. He had heard about Sponsors while incarcerated and wrote a letter asking for a spot, figuring it was his best chance for success after his release. The executive director, Paul Solomon, served time two decades ago for drug possession and bank robbery. He receives 50 such letters a week but has far fewer slots available. The wait list to join the program, in which clients pay a nominal fee for food and rent, is now about six months. Solomon wants applicants to show motivation to change their lives, but he accepts only those who are considered most likely to reoffend, based on what corrections experts call criminogenic risk factors: Do they have antisocial values, such as blaming others and a lack of remorse? Are most of their friends also criminals? Did they grow up in dysfunctional families? Do they have a history of substance abuse?

“Think about it. You just spent five or ten years in prison, you have no family support, no money, you’re walking out the door with a bus ticket and a mandate to meet with your parole officer and find housing,” Solomon told me. “How do you do that when you’ve got nothing?”

The compound’s main building, three stories high and meticulously maintained, can hold 60 men. They share two-person rooms, large common areas, and kitchens where they cook their own meals. A dozen men live next door in “honors housing” apartments, where they can stay on for up to a year. Sponsors has another five locations around the city with 78 more beds, including one site specifically for women and their children. Many clients receive cognitive behavioral therapy, in which counselors help them reframe and redirect negative thoughts and behaviors. Approximately 80 percent of clients also have drug and alcohol problems; to live in a Sponsors facility, they must attend treatment programs and abstain from using. Roughly 33 percent are sex offenders, who contend with added restrictions on where they can live and spend time—away from parks and schools, for example.

But just having a felony conviction, as an estimated 20 million Americans do, can be problem enough. In several states felons can’t vote, and until the recent Ban the Box campaign, most had to disclose their status on job applications, which is often a shortcut to the trash can. Landlords can reject them, too. In some areas, felons are excluded even from setting foot in public housing, which means they can’t visit family living there. “It’s a life sentence,” says Ann Jacobs, who runs the Prisoner Reentry Institute at New York’s . “You’re still a former felon. These civil penalties almost never go away.”

At the Sponsors resource center, staff guide clients through the basics of building a new life: getting an ID card and a copy of their birth certificate, enrolling in government assistance programs, learning how to use e-mail. They help them write résumés and coach them in interview skills. (Don’t dwell on the crime or prison time; acknowledge the mistakes and talk about the positive things you’ve done since then.) A whiteboard lists businesses where clients have found work in the past—like local restaurants and hotels—to save them time and frustration. In the warehouse, clients can pick up clothes for job interviews or furniture and household items when they move into their own apartments.

Such services might seem like an obvious way to help people get back on their feet, but they aren’t yet the norm. “Most of these reentry programs operate on a shoestring,” Jacobs says. “They’re underfunded and underdeveloped, and they don’t reach the majority of people.” Groups like Sponsors that provide several integrated services—particularly housing—under one roof are exceedingly rare, she says.

After one excursion with clients, she sent a picture to a donor agency and received a curt reply: We’re not paying for them to have fun.

Even in Lane County, Oregon, where Sponsors is located, most men and women released from prison don’t get the suite of transition options that Sponsors offers. Last fall, when I met with Donovan Dumire, Lane County’s head of probation and parole, he had 1,944 high- and medium-risk offenders under his watch. The 700 low-risk offenders, who have advantages like family support, positive social networks, and decent jobs, are treated with a more hands-off approach—keeping them on too tight a leash has been shown to increase their chances of returning to criminal behavior. Sponsors, founded 43 years ago by Catholic nuns and community activists, is the only reentry provider for Lane County and can house, at best, 500 people a year.

Many former inmates do end up back in prison. According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, which tracked 400,000 prisoners released in 2005, some 68 percent were rearrested or violated the terms of their parole within three years, and 77 percent did so within five years. If nothing else, this is hugely expensive. Between federal, state, and local jails, we spend about $80 billion a year housing prisoners. (The annual cost of keeping a single person incarcerated can run anywhere from $30,000 to more than $90,000.) Add in court fees and legal services, and the yearly total explodes to $260 billion.

Over the past 20 years, crime rates that tripled between the 1960s and 1980s fell by nearly half, but incarceration rates that ballooned in the 1990s stayed relatively steady, in part due to get-tough measures like mandatory minimums for drug offenses and three-strikes laws that impose long sentences for third convictions. As prison populations remained high, rehabilitation programs were slashed as money was channeled to more immediate needs like new facilities and additional staff. Though the national conversation has gradually shifted from warehousing prisoners to better preparing them to return to society, funding hasn’t caught up to ideology.

The federal government and many states are trying to shrink their prison populations, but for each inmate released, daunting challenges await, even with the support of robust programs like Sponsors. “And just to be real about this, we’re in Eugene, Oregon,” Solomon told me. “We’re not in Oakland or Detroit or other communities ravaged by economic disparity and hopelessness. We’re not sending people back to gang-infested neighborhoods.”

Most reentry programs, where they do exist, focus on housing, employment, and substance-abuse counseling. A roof, a job, and clean pee. That’s a good start, but it doesn’t make a life. Former inmates can have those things and still be miserable, and therefore more likely to fail. To succeed they need some enjoyment in their lives, hobbies, and supportive friends—all of which fall into another tier of criminogenic risk factors when estimating the likelihood of reoffense. Indeed, set against many states’ inability to help the formerly incarcerated with the basics, a hiking trip can seem frivolous.

“If you’re not happy, if you don’t have something to live for, you’ll go back to where you started,” Jackson told me. “Play and laughter is often a missing piece.”

One-on-one mentorship programs are becoming more common. Sponsors pairs the recently released with community members who will spend several hours with them each month on healthy activities, anything from hiking to dinner out to church services. Many former inmates, like Mike, also serve as mentors, friendly guides who have walked the same path.

Jen Jackson holds a bachelor’s degree in environmental humanities, with a focus on people’s connection to the natural world, and a master’s degree in adventure-based experiential education. She has mentored through Big Brothers Big Sisters, worked with at-risk youth in wilderness-therapy programs, and taught high school environmental science, art, and physical education using the outdoors for hands-on learning. She later began working for , the city of Eugene’s recreation program, which leads activities like kayaking, mountain biking, sailing, and snowshoeing. She came to Sponsors in 2010 and quickly started the outdoors program. “It was a no-brainer,” she says. “This was a culmination of all my life experiences and interests.”

Over the past six years, Jackson has run about 50 outdoors trips with Sponsors clients, taking them hiking, rafting, and crabbing on the coast. She is 34 and petite, with a small nose hoop and light brown hair that falls to her jaw. She lives in the forested hills outside Eugene, with a large garden, goats, and some chickens—a bucolic escape from hectic days. Sponsors clients don’t have that remove. On a sailing trip, one of the men in the mentoring program jumped into the water without a life preserver and ignored Jackson’s entreaties to get back in the boat. He couldn’t help himself, he told her later. He hadn’t been submerged in water for 25 years, and the sensation, the joy of the moment, overwhelmed him.

Jackson’s vision for outdoor therapy hasn’t always been well received by those who help fund Sponsors. After one excursion with clients, she sent a picture to a donor agency and received a curt reply: We’re not paying for them to have fun. That’s shortsighted. Sponsors clients in the mentorship program are 80 percent less likely than other former inmates in Lane County to reoffend.

For Tony, who is now 46, just wading through the aisles of options for socks and underwear at Walmart was enough to overwhelm him, never mind the fruitless job searches and the anxiety of explaining his past to complete strangers. At times he would sit at the bus stop and weep from frustration, unsure how to navigate the world into which he’d reemerged.

The brighter moments, few and cherished, carried him through the early months. Not long after his release, he went snowshoeing with Jackson in the Cascades, his first time back in the deep outdoors, and watched a hawk soar overhead in a cloudless sky. He counts that day as one of his best ever and a much needed counter to the relentless pressures of life post-prison. “The time really begins when you come back out to society, when you have to deal with the roadblocks and hurdles,” Tony said. “People have no clue how hard it is to get your life back.”

Ex-cons are not unlike soldiers returning from war. Now back among people who don’t understand where they’ve been, or how they’ve been changed by the experience, they are expected to resume or establish a role as functioning members of society. Yet they’ve been shaped by their time away, in a world ruled by alien norms, where at times they embraced behaviors at odds with civil society.

“My first night in prison was the scariest of my life,” Eric told me. His cellmate wouldn’t let him enter until he had inspected Eric’s paperwork, which shows a prisoner’s crime and sentence. Fortunately for Eric, he had “good paper,” which basically meant that he wasn’t a sex offender. (They don’t fare well in prison—they are often ostracized, assaulted, and extorted for money or snacks from the commissary.)

“He put me on the top bunk, and I had to ask permission to come down and use the bathroom,” Eric said. “People are yelling at each other, cussing. It didn’t quiet down until 10 p.m.” He kept to himself for several days and watched the other prisoners, the gang members in particular, the way they rolled their shoulders when they moved, a strut, a show of confidence and authority. He walked around the recreation yard, practicing his swagger.

“It’s a crash course, and the learning curve is almost vertical,” another Sponsors client told me. “It’s a very, very violent society.”

Some new inmates won’t leave their cells for days because they are too scared to enter the free-for-all of the open areas before they understand something of the power dynamics. Young prisoners in particular face huge pressures to join a gang, with promises of protection, friendship, and status. The chow hall is an easy place to spot the newbies,

who often stand with their backs to the wall, tray in hand, waiting for a table to open. Not one with an unoccupied seat, but a whole table, so they can be sure that they’re not sitting with the wrong people—gang members or, far worse, the sex offenders, who often form their own band of outcasts. Tony once accidentally sat down with a gang member, but the veteran inmate recognized that Tony had made a mistake, not a statement, and let it slide. He quickly learned that respect rules life in prison, where the seemingly innocuous can be interpreted as a deliberate affront, a test. “You step on someone’s shoe,” Tony said, “you best turn around and give your apologies.”

He spent the first two years of his sentence at the Snake River Correctional Institution, near the Idaho state line, where many other Sponsors clients had cycled through as well. The largest of Oregon’s 14 prisons, it’s one of the more violent, known among inmates as a “gladiator school.”

I visited Snake River on a cold fall morning. Located an hour northwest of Boise, it sits amid rolling hills, a complex of beige buildings ringed by high fences topped with razor wire that sparkles in the sun. Captain Thomas Jost and corrections officer Michael Lea met me at the front office and led me through a series of locked doors into the housing areas. Lea has worked here nearly 19 years, and Jost for 16. “There are guys that I’ve known for that long—we came here at the same time,” Jost said. “We kind of grew up together.” About 8 percent of Snake River’s 3,000 prisoners are serving life without parole; they’ll be in prison long after Jost and Lea retire. But the rest—like the clients at Sponsors—will eventually get out, which means that how they act here, how they’re treated, and whether they’re able to improve themselves matters a great deal.

We walked down the wide, high-ceilinged, brightly lit corridors that connect the housing units, each of which holds 80 inmates, with one officer overseeing them. The halls were empty, the inmates locked in their cells for one of six daily counts. They live in long, rectangular bays, where a common area separates two wings of ten small two-man cells. The inmates are always on display through two large windows, one in the door and another beside it. We peeked into a cell, where an inmate lay on the top bunk watching a ten-inch TV, its case made of clear plastic so that nothing could be hidden inside. A man of perhaps 50 sat on the bottom bunk, his left eye badly blackened and swollen to a thin slit.

“What happened to you?” Jost asked.

“I fell down.”

“Uh-huh,” said Jost.

Had an officer seen that fight, the assailant would likely be headed to segregation, or what we think of as solitary confinement. (Snake River calls it “special housing.”)

Inmates who violate prison rules, assault other inmates or officers, have persistent behavior problems, or can’t be in general population for their own or others’ safety live alone in roughly eight-by-twelve-foot cells. Stays range from a week to six months, but prisoners can be in segregation longer if they rack up too many infractions or are deemed a danger to others.

Just outside one of the segregation units, Jost and Lea showed me a chair-like device that scans the body for metal. Lea told me of an inmate who slid a whole paper clip into his heel through the thick callous.

“They have nothing but time,” he said.

“You’re hypervigilant in here,” Jost said.

Inmates in segregation wear orange jumpsuits instead of the denim pants and shirts worn in general population, and their hands are restrained anytime they’re escorted outside their cells. But that is rare—they spend 23 hours a day alone on lockdown.

Tony spent a week in Snake River segregation for fighting his roommate, and he told me that what he remembers most is the strange synergy of isolation and noise: alone in your head, with sounds bouncing off concrete as inmates yell at guards and to each other, some calling out chess moves between cells for games tracked on homemade paper boards. As Jost, Lea, and I passed through the main hall, where water from an overflowing toilet had puddled, an inmate shouted to us: “You guys are walking through shit water, just so you know.”

We climbed the stairs to a control room, where an officer kept watch. From this perch, they can see into cells on both floors, like looking at animals on display in a pet store. The lights are always on in the main room, which means the cells are never dark. In one, a man sat on the toilet, unspooling a length of toilet paper. In the next, a shirtless inmate did side planks. Televisions aren’t allowed in segregation, but a few were reading or calling between their cells. The rest slept or stared at the ceiling.

“Isolation is not good over time,” Jost said. “If you were stuck in that cell 23 hours a day, eventually you’d crack. We’ve seen guys come in normal and they just break down.” Snake River can house as many as 456 prisoners in segregation; nationwide, by one estimate, 80,000 prisoners are in solitary confinement at any given time. Inmates held alone, with limited human interaction, can suffer mental-health problems ranging from anxiety and insomnia to paranoia and depression. They’re more violent, and they kill themselves more often than other prisoners. For those who already have mental-health problems, as many do, time in solitary makes it all worse.

In good weather, inmates in Snake River’s general population have twice-daily yard time, for up to six hours total. They can play soccer, baseball, or basketball, run on the track, lift weights, throw horseshoes—rubber ones—or just lie in the turf. There’s fresh air but not much nature.

Those in solitary have barely any contact with the outdoors. For their daily 45 minutes outside their cells (not counting the 15 minutes they get to shower), inmates have

access to a recreation yard—a cement-floored space about 15 feet by 30 feet, with high cement walls. If they look up they can see the sky through a mesh grate, a narrow glimpse of the world beyond the prison. The lucky might see a bird fly over.

But the housing unit that Jost and Lea showed me had an indoor recreation room, too, and here, in a 15-by-12-foot space with high walls, I saw something remarkable and entirely out of place: on the far wall, in brilliant color, palm trees swayed in a tropical breeze, and water lapped at the sand. The sounds of gently breaking and retreating waves filled the room.

A projector mounted out of reach on the opposite wall displayed the six-by-nine-foot scene. A library of 38 clips included scenes of waves pounding rocks on the California coastline, a tranquil sunset, time-lapse images of clouds building and breaking, sweeping mountain vistas, and forests with birds singing. Ambient sounds accompanied some of the videos. Others were paired with classical music.

This was the Blue Room, a first-of-its-kind effort to connect the most isolated prisoners with the natural world. And its presence in a penitentiary says much about both the power of nature to soothe the human mind and an ongoing shift within the corrections system, from punishment to rehabilitation.

, the inventor of the Blue Room, is an ecologist who, in 1980, started studying the Costa Rican rainforest by using rock-climbing equipment to ascend high into the canopy. The importance and inherent benefits of trees seemed obvious to her, but she realized that many didn’t share her connection to the natural world, so she embarked on a public education campaign. She gave sermons at churches and synagogues about trees and spirituality, worked with rappers to reach inner-city kids, and took lawmakers on climbing trips into the treetops. A decade ago, she started a science-education project in a Washington state prison, where she taught minimum-security inmates to grow moss and raise endangered butterflies and frogs.

The prisoners in Nadkarni’s project had the highest level of privileges among the inmates, including opportunities to interact with the natural world. With good behavior, inmates in some prisons can earn spots on work crews to landscape local parks, pick up trash along highways, or maintain walking trails. Several states have farm programs, with inmates raising livestock, running dairies, and growing vegetables for use in the prison or to donate to nearby communities. Inmates on wildfire crews enjoy perhaps the greatest immersion in nature. (Of course, the impetus is cheap labor, not improving participants’ mental well-being.) Both Tony and Brian had worked on outdoor crews—cutting lawns, raking leaves. “The worst part of the day,” Tony told me, “was having to go back.”

Nadkarni wondered: What of the prisoners most removed from the natural world? While scientists had long studied the mental-health effects of solitary confinement, no one looked at the effects of nature on those most distant from it. Prison offered the perfect laboratory. “If we had tried to do an experiment—let’s keep men away from nature for seven years, then reintroduce nature and see what happens to them—it would have been impossible,” Nadkarni told me. “It would have been unethical.”

Research on nature’s role in other institutional settings suggested to Nadkarni that prisoners would experience the same benefits. For instance, patients who could see trees outside their windows at a Pennsylvania hospital recovered faster from gallbladder surgery than patients whose windows looked out on a brick wall. They needed fewer painkillers, had fewer complications, and complained to nurses less frequently. Nature imagery on hospital walls eases patient stress, herb and flower gardens in dementia wards can calm residents and reduce violent outbursts, and public housing developments that incorporate trees and natural spaces have lower crime rates and promote stronger social bonds among neighbors than those that don’t. “When you surround people with nature, you can get a change in behavior,” Nadkarni, 61, said. “People respond positively—physiologically, psychologically, emotionally.”

In 2008, she approached a Washington prison about a nature-imagery program for inmates in solitary confinement, but corrections officers there said it would coddle prisoners. Two years later, a Snake River corrections officer watched Nadkarni’s TED Talk and called her. This time she didn’t pitch the nature imagery as stress reduction for prisoners; rather, she said that the program could make officers safer by improving inmates’ behavior.

Lea, who worked in the intensive management unit at the time, built the projection system in 2013. “I was just tired of listening to them gripe the whole day,” he said. “If I can get them to shut up for an hour, that’s golden.” The Blue Room, named for the color the walls were painted, succeeded in quieting the inmates, but it did a lot more than that. They received fewer disciplinary infractions than inmates in other segregation units, and prison staff said they required fewer cell extractions, in which teams of corrections officers physically��remove unruly inmates.

Patricia Hasbach, an eco-psychologist on Nadkarni’s team, interviewed six inmates about their Blue Room experience and found that the imagery helped them with self-regulation, the ability to resist their worst impulses—a skill that’s degraded by time in solitary. They often recalled the experience hours later to calm themselves. Many said they thought the videos helped them sleep. Inmates can use the room every other day for up to 45 minutes. They can sit on a cushion, but many exercise, walk around as the videos play, or stand a few feet from the projection, the natural world filling their view. Most of the inmates she interviewed—like many prisoners in the U.S. today—hadn’t spent much time in nature before they were incarcerated, so the Blue Room didn’t help them recall pleasant memories. Instead it was the imagery itself, and the emotions it conjured, that calmed them.

The project has also given corrections officers a tool to head off potentially unruly behavior in inmates. Hasbach heard this during interviews with staff, and Jost and Lea told me the same. If they see an inmate who seems agitated or has become unusually quiet, they might ask if he wants time in the Blue Room.

Inmates can sit on a cushion, but many exercise, walk around as the videos play, or stand a few feet from the projection, the natural world filling their view.

“They can’t go down the street to be alone,” Jost said, and Lea picked up his thought: “But they can go in that room and be in a forest.”

A prisoner in the cell nearest to the Blue Room had been eavesdropping. “They can talk all the bullshit they want about that room,” he shouted. “You can’t be locked in a cell for over a year and not start losing your mind.” The inmate was a regular in the Blue Room. “That guy would be the first one to freak out if we took this out,” Lea said.

Twenty-four of the prisoners currently in segregation will be paroled within months, with very little time in general population as a transition. “How do you think they’re going to react if they’ve been stuck in a cell 23 hours a day?” Jost said. “What are we trying to push back to the street?”

Many states have reduced the use of solitary confinement in recent years, and last year the federal government banned solitary for juvenile offenders in federal prison and prohibited its use for minor infractions. Advocacy groups say this doesn’t go far enough. They want solitary abolished altogether, which has brought Nadkarni criticism—and some nasty e-mails—for her Blue Room work. By making solitary more palatable, some have told her, she’s helping maintain an inhumane practice. “I do understand where they’re coming from, but we’re not going to abolish prisons,” she told me. “All I can do is provide as many prisoners as I can with the healing power of nature as a way to mitigate some of the negative things that go on in prisons today and to make them more productive, better people when they come out.”

Snake River hopes to add Blue Rooms to its other segregation and general-population units. A controlled study with a larger sample size is now under way, but preliminary results generated interest from facilities in Alaska, South Carolina, Rhode Island, and even the Washington prison that originally turned down Nadkarni’s proposal. Prisons in Wisconsin and Nebraska just opened their own versions of the Blue Room. Last year a sheriff from Utah embraced the idea when he discussed it with Nadkarni. “We keep getting more and more punitive, taking away their privileges, subtracting what they’re able to do,” she��remembered him saying. “It’s not working.”

When Jackson and her Sponsors clients first arrived along the McKenzie for their fishing trip, they gathered under a riverside pavilion, out of the spitting rain, and their guide for the day, Jonathan Blanco, explained the seams and pools where trout could be found. He mounted a few vises to the picnic tables and guided the group through the fine and frustrating work of fly tying.

“I’m going to give it a whirl, but I don’t see this being my talent,” Tony said as he spiraled thread around what would become a woolly bugger. Tony is thoughtful and earnest, with a ruddy face and close-cropped, graying hair. His tongue poked from the corner of his mouth as he concentrated. “What happens if the thread breaks?” he asked.

“You just wrap right over it,” Blanco said.

Blanco, who is 35 and quick to smile, started tying flies at age eight and was doing so professionally at 15. He built his first fly rod at 18 and now has his own rod-building business, a side gig to his 14-year career at the Oregon Department of Corrections.

Prisoners and corrections officers are both shaped by the struggle for control and respect. Blanco had seen himself as an enforcer, tasked with reminding inmates that they had done wrong and had forfeited their rights to freedom. “I made life a living hell for some guys,” he said. “I’m five-foot-six, and I weighed 130 pounds when I started. I had to be aggressive.” He was a taser and firearms instructor, and spent more than three years with prison SWAT teams, called in to break up fights and subdue unruly inmates. “I’ve had things turn ugly,” he told me. “The only way to get through that was to dehumanize the individuals we were working with.”

Blanco worked on death row at Oregon State Penitentiary for two years, then met an advocate for inmates whose own father, a corrections officer, had been murdered by a prisoner. How could he work with inmates when one had taken so much from him? Blanco asked. By helping prisoners, the man told him, he was keeping others safe, maybe preventing another murder.

In 2012, Blanco transferred to the prison’s hobby shop and helped inmates establish their own online handicraft businesses, selling jewelry, leather goods, and artwork. He now runs the prison arts programs statewide, though he’s still learning to dial back who he’d become as a corrections officer. “What helped was nature,” he said. “Going outside, that’s my outlet.” He fishes or hikes most weekends—and on the occasional mental-health weekday—and hoped these men would find the same relief. “Some of them give up quickly,” even committing new crimes just to return to a world they understand, he told me. “Going out into the woods may give them enough solitude to take a deep breath.”

He led the group onto the grass and gave a quick lesson in casting, the wrist fixed and the forearm gliding like a metronome from 11 o’clock to two and back again. They fished the river for several hours. Brian, working a hole by a downed snag, caught a single rainbow trout. The other six came from Mike, who opted to spin-cast with worms.

They gathered again in the late afternoon under the pavilion to cook their catch. The rain had stopped and the clouds had thinned, with a hopeful patch of blue in the western sky. As they nibbled on the trout, Jackson asked them to discuss the pressures they faced and what might ease them.

“How do you find time day to day to step back?” she asked.

“I’ll just walk around the block, look at the trees, the colors,” Tony said. “A five, ten-minute walk and I’m able to regroup.”

Jackson nodded and smiled. Just as a 45-minute session in the Blue Room can’t counteract all the effects of prison, a trip into the outdoors every month or two doesn’t erase the daily stressors. That’s the shortcoming of such programs: the impacts are lessened if exposure isn’t maintained or revisited, even in small doses. “We’re working with the most marginalized people, and there are a lot of barriers to recreation,” Jackson said as we drove back into town. “There’s transportation, there’s time, there’s money. But what is nature and what is recreation? It’s not that nature and the outdoors is this other place you go—it’s right here. It’s what’s right outside the window, or on the walk between your two or three jobs.”

The next morning, I toured the grounds at Sponsors and saw its nearby nature, a moment of peace within easy reach, where clients can sit by the meandering flower garden or help work the five large raised beds, which in summer are crowded with beets and squash, corn and tomatoes, strawberries and blueberries. The importance that Sponsors places on time spent outdoors can be seen in the bright and sprawling mural painted across a wall behind the garden. Sketched by a local artist and painted by the clients, it depicts the prisoner’s journey from the bleak setting of incarceration to a vibrant landscape where he’s embraced and supported. In the middle of the mural, surrounded by sunlight, the man kneels and drinks from a mountain stream.

In a renovated garage beside the mural, I found Wayne, who runs Sponsors’ fledgling bike shop. With his wallet chain, tatted forearms, and thick brown goatee, he still looked much like the hard-drinking, hard-swinging biker he’d been before prison.

About half of Sponsors’ clients can’t drive. Some lost their license for drunk driving or nonpayment of child support; others can’t afford a car and insurance. “When you get out, you don’t have any freedom,” Wayne said as he unwound a coil of brake cable. With bicycles they can ride to interviews and appointments or just cruise along the riverside paths for some exercise and relaxation.

Every few months, the Eugene police department donates a couple dozen confiscated and abandoned bikes. Some just need a tune-up; others Wayne cannibalizes for a growing inventory of spare parts. That morning he had loaned out three bikes.

Another, a Trek mountain bike halfway through a rebuild, hung in a Park floor stand. He’d just received several light kits for anyone who needed to ride at night. A few stop in each day with flat tires, squirrelly derailleurs, squeaky brakes. He wants the shop to become a gathering spot, where clients can learn to work on their own bikes.

Wayne had racked up three drunk-driving arrests and lost his license but kept driving, which earned him two years in prison. There he cleaned himself up, started going to church and Alcoholics Anonymous; getting right, he calls it. Since his release last March, cycling had become a core element of his life, for both logistics and enjoyment. His girlfriend offers him rides in her car, but he usually declines, preferring the independence of his bike, clear skies or rain. He rides an electric bike around town and bought a Specialized Crave Comp 29er for trail and downhill riding. He had also made new friends at local bike shops and on the trails. “You lose your friends when you go to prison, and you have to stay away from them when you get out, if you want to stay out of prison,” he said. “The majority of the people you hung out with have the same problem you did. You feel really lonely.”

Later that afternoon, I drove with Tony into the hills south of Eugene for a hike up Spencer Butte, and he spoke of loneliness, too. He told me about the first night in his own apartment after his 90 days at Sponsors, after the friends who helped him move had left, when the quiet and solitude had overwhelmed him. “The fear set in,” he said. “The fear of being alone. You don’t know how to manage on your own anymore.”

He would like to counsel troubled youth someday, to help them avoid the bad choices he didn’t. “Nip it in the bud,” he said. He still has his own struggles. He wasn’t getting enough house-painting work, Sponsors staff suspected he’d started drinking again, and he’d been arrested a few months earlier for misdemeanor assault and spent several days in jail. For much of the summer, he slept in a tent by the river in a Eugene park, returning there each night after work. He presented this time to me as an extended camping trip, but when I mentioned it to Jackson, she offered a different perspective: The camping was partly by necessity. He was between housing during that period, but whether by circumstance or choice, he spoke of the experience with what sounded like genuine pleasure and appreciation.

Last summer, Tony also bought a used blue kayak, and he often loaded it into his pickup truck and drove to a series of ponds north of town, where he had canoed with his stepfather as a boy. On one kayaking trip, three small ducks jumped on his bow. “It gives you a tender moment,” he said. “I carry that with me.”

We set off down the trail, a late-day sun pushing bars of golden light through the fall foliage. Tony stepped lightly over rocks and tree roots in paint-spattered leather boots. In these woods he was merely a hiker, and the many people we passed, the dog walkers and college kids and trail runners, offered friendly nods and greetings, bonded, for a moment, by a shared enjoyment of nature. We rounded a corner on the trail and Tony glimpsed the summit, a short climb away. He sucked a breath and sighed. “I see that,” he said, “and everything just leaves my head.”

Former inmates are identified by first name only; sponsors clients written about in the past have lost jobs after coworkers and others read about their criminal backgrounds.

Brian Mockenhaupt is an �����ԹϺ��� contributing editor.