There’s tons of evidence, from hundreds of studies with hundreds of thousands of participants, showing that exercise is an effective tool to combat depression and other mental health issues like anxiety. These studies find that it’s at least as good as drugs or therapy, and perhaps . It’s now recommended in official guidelines around the world as a or treatment. Still, there’s an important caveat to consider: is all this evidence of a connection between exercise and mental health any good?

That’s the question debated in in Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, based on a symposium held at the annual meeting of the American College of Sports Medicine. Four researchers, led by Patrick O’Connor of the University of Georgia, sift and weigh the various lines of evidence. Their conclusion is mixed: yes, there’s a relationship between exercise and mental health, but its real-world applicability isn’t as clear as you might think.

The Observational Evidence on Exercise and Mental Health

O’Connor and his colleagues assess three main types of evidence. The first is observational studies, which measure levels of physical activity and mental health in large groups of people to see if they’re connected, and in some cases follow up over many years to see how those relationships evolve. The headline result here is pretty clear: people who are more physically active are less likely to suffer from depression and anxiety now and in the future.

Observational studies also suggest, albeit more weakly, that there’s a dose-response relationship between exercise and mental health: more is better. is enough to produce an effect, but higher amounts produce a bigger effect. It’s an open question, though, whether doing too much can actually hurt your mental health. Some studies, for example, have found links between overtraining in endurance athletes and symptoms of depression.

The big problem with observational studies is the question of causation. Are active people less likely to become depressed, or is it that people who are depressed are less likely to be active? To answer that, we need a different type of study.

The Evidence from Randomized Trials

The second line of evidence is from randomized control trials, or RCTs: tell one group of people to exercise, tell another group not to, and see if they fare differently. Overall, the evidence from RCTs lines up with the observational evidence: prescribing exercise improves or prevents the occurrence of depression and anxiety.

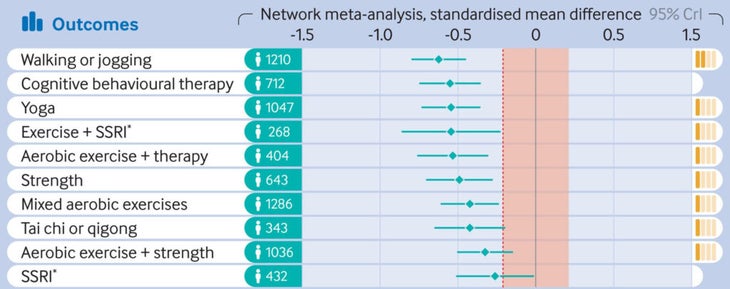

For example, here’s a graph from a 2024 meta-analysis of 218 RCTs with a total of over 14,000 participants, :

Dots that are farther to the left indicate how much a treatment aided depression compared to a control group. Notice that walking or jogging ranks slightly above cognitive behavioral therapy and far above SSRI drugs. That’s an encouraging picture.

The evidence still isn’t bulletproof, though. One problem is that it’s very difficult to avoid placebo effects. Participants who are randomized to exercise know that they’re exercising, and likely also know that it’s supposed to make them feel better. Conversely, those who sign up for an exercise-and-depression study and are assigned to not exercise will expect to get nothing from it. These expectations matter, especially when you’re looking at a difficult-to-measure outcome like mental health.

Another challenge is the timeframe. Exercise studies are time-consuming and expensive to run, so they seldom last more than six months. But a third of major depressive episodes spontaneously resolve within six months with no treatment, which is in part why FDA guidelines suggest that such trials should last two years, to ensure that results are real and durable.

Why Context Matters When Studying Exercise and Mental Health

The third and final body of evidence that O’Connor and his colleagues dig into is the contextual details. Exercise itself seems to matter, they write, but “who we play with, whether we have fun, whether we are cheered or booed, and whether we leave the experience feeling proud and accepted, or shamed and rejected also matters.”

For example, most of the research focuses on “leisure time physical activity,” meaning sports and fitness. But there are other types of physical activity: occupational (at work), transportation (active commuting), and domestic (chores around the house). Is there a difference between lifting weights in the gym and lifting lumber on a construction site? Between a walk in the park and a walk down the aisle of a warehouse?

One view of exercise’s brain benefits is that it’s all about neurotransmitters: getting the heart pumping produces endorphins and oxytocin and various other mood-altering chemicals. If that’s the case, then manual labor should be as powerful as sports, and working out alone in a dark basement should be just as good as meeting friends for a run on a sunny day. Both intuition and research suggest that this isn’t the case.

Instead, some of exercise’s apparent mental-health benefits are clearly contextual. Doing something that creates social connection and provides a feeling of accomplishment is probably helpful even if your heart rate doesn’t budge above its resting level. And conversely, an exercise program that leaves you feeling worse about yourself—think of the cliché of old-school phys ed classes—might not help your mental health regardless of how much it boosts your VO2 max.

This is where the big research gaps are, according to O’Connor and his colleagues. It’s pretty clear at this point that exercise isn’t just correlated with mental health; it can change it. But the best ways to deploy it in the real world remains understudied. For now, the best advice is probably to follow your instincts. Don’t stress about what type of exercise you’re doing, how hard to push, or how long to go. For improving mental health, these variables seem to have surprisingly weak effects. Instead, focus on the big levers: whether you’re enjoying it, and whether you’ll do it again tomorrow.

For more Sweat Science, join me on and , sign up for the , and check out my forthcoming book .