On January 1, 2024, will kick in that officially bans tramadol, an opioid painkiller. It’s been a long time coming: the abuse of tramadol has been an open secret in cycling, with about its use by Team Sky and British Cycling. “It kills the pain in your legs, and you can push really hard,” former Team Sky rider Michael Barry . found tramadol in 4.4 percent of all samples from cyclists, leading to worries that tramadol-addled riders would cause crashes in the peloton. For some athletes, like , tramadol was a gateway to full-blown opioid addiction. The International Cycling Union banned it in 2019, but WADA continued to take a wait-and-see approach.

The data that finally changed WADA’s mind has in the Journal of Applied Physiology, where it’s free to read. A group led by Alexis Mauger of the University of Kent in Britain put 27 highly trained cyclists through a series of performance tests with either 100 milligrams of tramadol (a modest dose: Kirkland was taking as much as 20 times that amount at once) or a taste-matched placebo. The riders were, on average, 1.3 percent faster in a 25-mile time trial when taking tramadol. WADA’s rules require that a substance fulfill two of three conditions to be banned: it enhances performance, has the potential to harm the athlete, and violates the spirit of sport. Mauger’s data sealed tramadol’s fate.

That’s the simple part of the story. Or at least, the relatively simple part. Admittedly, previous studies of tramadol’s performance-boosting effects have produced mixed results. Mauger and his colleagues argue that these previous studies have featured performance tests that weren’t long or hard enough for pain control to matter, failed to exclude participants who had side effects like vomiting from the drug, or muddied the waters by having cyclists complete cognitive tests while they tried to race. It’s also worth asking whether the benefits of a painkiller might be exaggerated in a test where the subjects are forced to fixate on their own discomfort, giving continuous ratings of exactly how much they’re hurting, compared to the real world. Still, the new results make a strong case that tramadol boosts performance and should thus be banned. The harder question is why it works.

In 2010, Mauger published showing a 2 percent boost for cyclists taking a simple dose of Tylenol. He has followed up with other studies using various techniques like saline injections to manipulate exercise-associated pain. In Mauger’s view, pain is one of the sensations that causes us to slow down or stop during endurance exercise, so the tramadol results make perfect sense.

Not everyone agrees, though. When I wrote about Mauger’s research on pain in 2020, I noted that other researchers such as Walter Staiano and Samuele Marcora believe that subjective perception of effort (“the struggle to continue against a mounting desire to stop”) is more important than pain (“the conscious sensation of aching and burning in the active muscles”). Staiano and Marcora have published supporting their contention that we quit when effort maxes out, even when the pain we’re experiencing is still tolerable. There may be ways of reconciling these two views: perhaps the cognitive effort of managing increased pain makes exercise feel more effortful, for example. But it’s still an open debate, which makes any new data on the question particularly interesting.

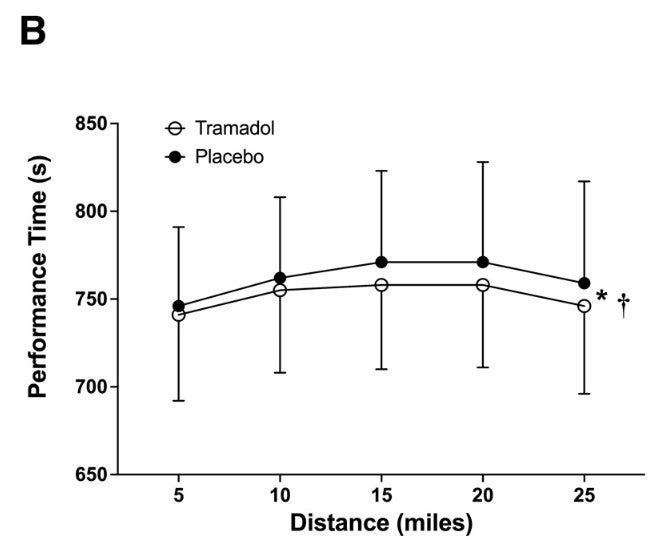

And the details of Mauger’s data, it turns out, are indeed curious. For starters, here are the five-mile splits for the tramadol (open circles) and placebo (closed circles) conditions in the 25-mile time trial:

The tramadol riders are pulling ahead right from the first split, and continue to widen their lead throughout the trial. One interesting wrinkle: riders who scored higher on a psychological test of pain resilience—that is, those who felt they had better ability to regulate their emotions and thoughts about pain—tended to get a bigger performance boost from tramadol. To be honest, this is the exact opposite of what I expected: I would have guessed that those who struggle most with managing pain would get the biggest benefit from reducing it.

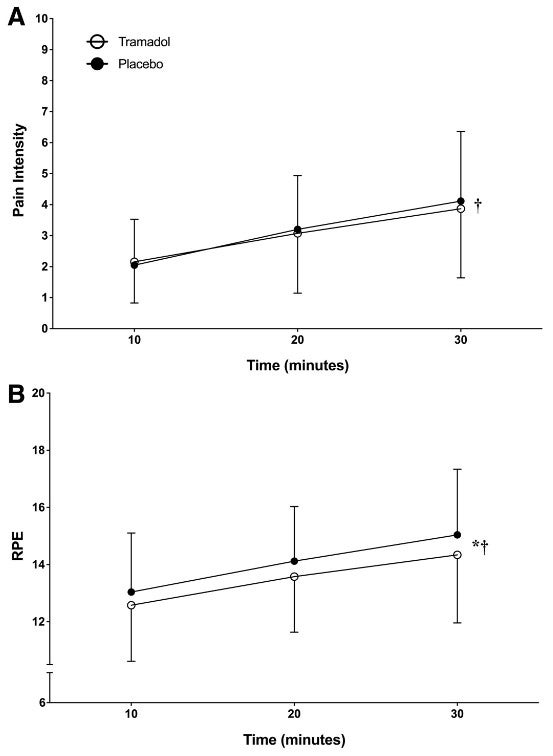

Immediately before the time trial, the cyclists did a 30-minute ride at a hard but steady predetermined pace, while rating their perceived effort every five minutes and continuously noting any changes in their perceived pain. Here’s what that data looked like (pain above, effort or RPE below):

Now we have a conundrum. Tramadol, an opioid painkiller, appears to have had no effect whatsoever on the pain experienced during cycling. On the other hand, it significantly lowered the perception of effort, which in turn—as predicted by Staiano and Marcora—improved performance. Mauger and his colleagues aren’t sure how to explain this: they suggest that the continuous self-reporting of pain, as opposed to being asked about it every five minutes, might have made it harder to pick up small changes. I’m not sure what to make of this finding, but it reaffirms my sense that we still have a lot to learn about how pain and effort and other related constructs like mental fatigue influence our performance.

As for tramadol, its new status will end the longstanding ambiguity about its use. Nairo Quintana, the Colombian cycling star, —twice—during the 2022 Tour de France, and was stripped of his sixth-place finish. But it was deemed a medical issue rather than a doping positive, since tramadol wasn’t banned by WADA, and thus carried no suspension. Starting next year, any athlete caught using it won’t be so lucky.

For more Sweat Science, join me on and , sign up for the , and check out my book .