I’ve always been partial to Dunbar, the character in Catch-22 who seeks out boredom and discomfort in order to make time pass more slowly, thus effectively prolonging his life. It’s a sensation that’s familiar to any endurance athlete: the seconds agonizingly stretching as your effort mounts. Forget cardiovascular benefits and weight control; maybe the real life-extending power of exercise is the way it distorts your time perception.

That sensation is the topic of , by a research team led by Andrew Edwards of Canterbury Christ Church University in Britain. Edwards and his colleagues put a group of 33 volunteers through a series of all-out, 4-kilometer cycling time trials, periodically asking them to estimate the passage of 30 seconds. Sure enough, hammering made the cyclists’ internal clocks faster, which in turn made the efforts feel longer—but not quite in the way the researchers expected. Instead, the results join a series of recent studies suggesting there’s more to time perception than even Dunbar might have suspected.

Back in 2017, Edwards and a colleague one of the first studies of exercise and time perception. They found that in rowing and cycling bouts between 30 seconds and 20 minutes, people could estimate time fairly accurately during light exercise. But their subjective clocks began to speed up compared to the actual passage of time during moderate exercise, and accelerated even more in all-out bouts. For example, they were asked to guess when they were a quarter, halfway, three-quarters, and all the way through their 20-minute rowing trial. At their halfway estimate, only about 9 minutes and 20 seconds had passed, meaning their internal clocks were running 7 percent faster than real chronological time. By the time they reached what they thought was the finish, just 17 minutes had passed, a deviation of 15 percent.

How Workouts Can Distort Time Perception

Scientists aren’t sure exactly how we keep track of time, but the most common explanation for time dilation is that it’s influenced by how much information flows to your brain. During intense arousal—like hard exercise or perceived danger—our senses are heightened. Since we’re noticing more things per unit time, we tend to overestimate how much time has passed. So it makes sense that hard exercise warps time more than easy exercise. It also suggests that distractions, like the presence of a teammate or competitor, might help counteract the effect.

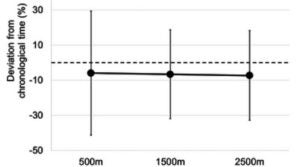

The new study tested the latter idea by having each competitor do a solo time trial, one with a virtual reality companion who cycled alongside them, and one with a virtual competitor whom they were instructed to try to beat. Contrary to expectations, neither the companion nor the competitor made any difference to time perception. And the time perception measured at 500 meters, 1,500 meters, and 2,500 meters was the same each time, even though the cyclists were working a lot harder at 2,500 meters than at 500 meters.

Here’s what that data looks like: a fairly constant clock deviation of about 7 percent at each timepoint.

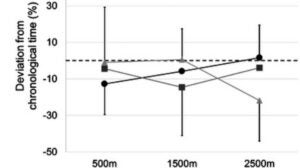

You can come up with various explanations for these results. It may be that exercising for a set time produces different effects than racing over a set distance. Or it may be that there are nuances that get lost when you look at overall averages. Here’s the same data, this time broken down into the solo time trial condition (circles), companion (squares), and competitor (triangles):

Looking just at the triangles, you see that when racing against a competitor, there’s basically no time deviation at 500 or 1,500 meters: the distraction of focusing on a rival eliminates the time effect. But at 2,500 meters, when the race is really getting hard (the virtual rivals were set to ride 5 percent faster than each subject’s baseline performance), time dilation balloons to more than 25 percent! You can probably come up with similar stories to explain the other two conditions, but these are post hoc explanations that should be treated with suspicion. For now, the safest conclusion is that the picture is more complex than we thought, and we’re not yet sure why.

Why More Research Is Required

The picture is similarly hazy when you look at time perception during strength training. Last year, David Behm and his colleagues at Memorial University of Newfoundland published a of exploring the effect of isometric knee extensions (that’s when you try to straighten your legs against an immovable object) on time perception. In some cases, pushing harder produced more time dilation; in other cases, intensity didn’t seem to matter, perhaps because the subjects were also distracted by monitoring their force output on a computer screen.

And earlier this year, Behm and his colleagues published testing time perception after physical exercise and also after a brain task that caused mental fatigue. Physical fatigue made time dilate but mental fatigue didn’t. That’s an interesting observation, but it conflicts with Edwards’s study, where time perception was back to normal within two minutes after exercise.

In other words, the more scientists study exercise and time perception, the more complicated it gets. All of these studies use different exercise protocols, different durations, and different ways of assessing time perception. It will take time to sort through the reasons for the apparent contradictions, but the overall finding still seems solid: time slows down when you’re pushing hard. Admittedly, as a means of life extension, it’s no picnic. “Maybe a long life does have to be filled with many unpleasant conditions if it’s to seem long,” one of Dunbar’s comrades says. “But in that event, who wants one?”

“I do,” Dunbar replies.

“W���?”

“What else is there?

For more Sweat Science, join me on and , sign up for the , and check out my book .